The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 and the American Economic Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 where

Question:

The Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 and the American Economic Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 where the latest big experiments the U.S. has undertaken with large-scale fiscal stimulus. Recall that the purpose of fiscal stimulus is to increase either AD or AS with some combination of government spending or tax cuts. John Taylor is a prominent critic of this type of stimulus. The reading below is not an article, but Congressional testimony Taylor gave to the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. In it, he provides some arguments for why the ARRA was not effective in stimulating growth or reducing unemployment following the Great Recession. Read pages 1-6 then answer the following questions:

john taylor 2009-Stimulus-two-years-later.pdf (pages 1-6 posted below)

1. The ARRA of 2009 and the ESA of 2008 are described as "Keynesian" fiscal stimulus bills. Why?

2. What were the spending components of the ARRA, as described by Taylor? What percentage of the total spending in the ARRA went to each component? Is this information surprising to you in light of what you know about how the spending multiplier works?

3. This question is closely related to #2. Why where federal income transfers to the states ineffective as stimulus efforts?

The 2009 Stimulus Package: Two Years Later

John B. Taylor*

Testimony Before the

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

Subcommittee on Regulatory Affairs, Stimulus Oversight and Government Spending

U.S. House of Representatives

February 16, 2011

Chairman Jordon, Ranking Member Kucinich, and other members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify on the impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, enacted two years ago this week.

My empirical research during the past two years shows that ARRA did not have a significant impact in stimulating the economy.

1 I do not think this finding should come as a surprise. Earlier research on the discretionary countercyclical Economic Stimulus Act of 2008—enacted three years ago this week—indicates that it too did little to stimulate the economy.

2 Research on the discretionary countercyclical actions in the late 1960s and 1970s—the most recent period of such large interventions prior to this past decade—also shows disappointing results, including high unemployment, high inflation, high interest rates, and frequent recessions; the poor results of the 1970s policies led top macroeconomists to write influential papers, such as “After Keynesian Macroeconomics,” which questioned the whole approach and to decry “that countercyclical discretionary fiscal policy is neither desirable nor politically feasible.”

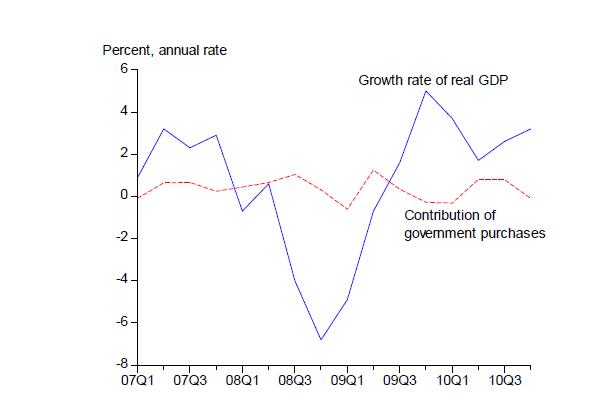

3 My purpose here today is not to explain this recent revival of a failed approach to policy, but rather to summarize the facts which once again raise doubts about its effectiveness. I take a macroeconomic perspective, looking at the impact of ARRA on the major components of GDP, such as government purchases and consumption expenditures. Changes in GDP are of course directly related to employment growth, with faster growth of GDP creating more jobs. I make use of a new data set developed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) at the Department of Commerce which traces the impact of ARRA on the economy through the National Income and Product Accounts, the major source of data for macroeconomic analysis. I present and analyze the data through a series of simple graphs, but the findings can be verified and supported through statistical analysis.

* Mary and Robert Raymond Professor of Economics at Stanford University and George P. Shultz Senior Fellow in Economics at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution

1 Much of this research has been conducted jointly; see for example Cogan, Cwik, Taylor and Wieland (2010), Cogan and Taylor (2010), Taylor (2010), and Taylor (2011)

2 Taylor (2009)

3 Examples of papers on temporary tax cuts and countercyclical grants to states are Blinder (1981) and Gramlich (1979), respectively; the paper about after Keynesian macroeconomics is by Lucas and Sargent (1978) and the quote is from Eichenbaum (1997) 2

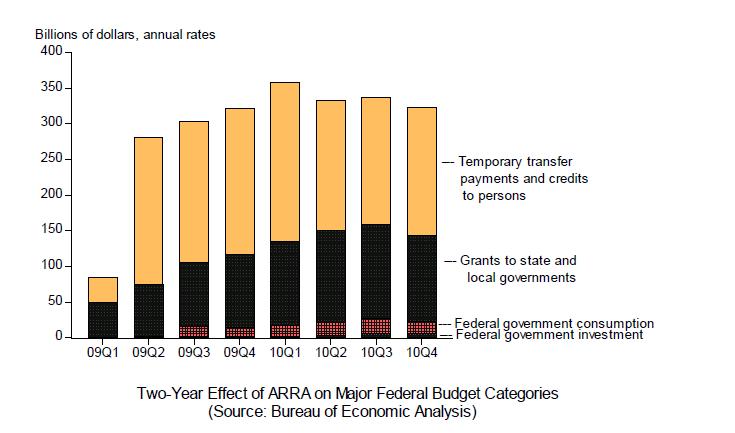

The Major Macroeconomic Components of ARRA

The bar chart below summarizes the impact of ARRA on federal government sector transactions during the two years or eight quarters since enactment.4 Three components of ARRA are highlighted:

(1) Federal government purchases of goods and services (both government consumption and government investment),

(2) Federal grants to states and local governments, and

(3) Temporary transfers and credits which increase the disposable personal income of individuals and families.

For the purposes of assessing the impact of ARRA on the economy it is very important to distinguish between these three categories and consider each in turn. 5

4 The data are from the BEA table “The Effect of the ARRA on Selected Federal Government Sector

Transactions” posted on the BEA webpage.

5 A small part of ARRA—not shown in the bar chart—was classified as going to the business sector in the form of subsidies and tax benefits, for example for renewable energy or first time home buyers credits, which I do not consider in this testimony. It should also be emphasized that ARRA is one of many other fiscal interventions during the past two years, including the cash-for-clunkers program and an unusually large increase in appropriated funds not officially counted as part of ARRA. See Anderson (2011) for details.

Billions of dollars, annual rates

--- Federal government investment

--- Federal government consumption

--- Grants to state and

local governments

--- Temporary transfer

payments and credits

to persons

Two-Year Effect of ARRA on Major Federal Budget Categories

3 The first category, government purchases of goods and services, is part of GDP and thereby contributes directly to changes in GDP. The amount by which an increase in government purchases in a stimulus package raises GDP is called the government purchases multiplier which has been a subject of much disagreement among economists in the two years since ARRA was enacted. Those who argue that the ARRA has been effective typically assume a large multiplier. Those who argue that the effects are small usually use models with a small multiplier.6

The second and third components of ARRA are not direct purchases of goods and services but rather transfers (grants) to state and local governments and transfers (one-time payments and tax credits) to persons. Such transfers are not part of GDP, but if and when the transferred funds are used by governments or persons to purchase goods and services—cars, trucks, food, health care, etc—those purchases are part of GDP. So the task of determining how much ARRA affects GDP requires looking at how much of those transfers are used for state and local government purchases and how much are used for personal consumption expenditures by households.

I now consider each category, starting with federal government purchases. Federal Government Purchases

Perhaps the most striking finding in the data shown in the bar chart is that only a tiny slice of ARRA has gone to purchases of goods and services by the federal government. Of the total $862 billion in the ARRA stimulus package, the amount allocated to federal government consumption summed to only $24.2 billion in the two years 2009 and 2010. The amount allocated to infrastructure investment at the federal level was $5.6 billion in 2009-10, or only 0.6 percent of the total ARRA.

Measured as a percentage of GDP the amounts are even smaller. At the maximum level, reached in the third quarter of 2010, federal government purchases were only 0.2 percent of GDP

and federal infrastructure was only 0.04 percent of GDP.

Clearly these amounts are too small to be a factor in the economic recovery. The debate over the size of the government purchases multiplier does not matter here because the multiplier has virtually nothing to multiply at the federal level. On this account ARRA has not been effective in stimulating economic growth and job creation.

6 For example, Romer and Bernstein (2009) assume a government purchases multiplier much higher than Cogan, Cwik, Taylor and Wieland (2010) and thus estimate an impact of ARRA which is six times greater. The models stressed by Cogan, Cwik, Taylor and Wieland (2010) are of a new Keynesian variety developed, for example, by Frank Smets, Director of Research at the European Central Bank, and his colleague Raf Wouters. Another newer model comes from an International Monetary Fund study which reports estimates of government spending impacts which are much smaller than those reported by Romer and Bernstein. A multiplier that is less than one means that government spending immediately crowds out other components of GDP (investment, consumption, net exports).

4

State and Local Government Purchases

State and local governments received substantial grants under ARRA as shown in the bar chart. The assumed purpose of sending these grants to the states was to encourage them to start infrastructure projects and make other government purchases which would add directly to GDP and create jobs.

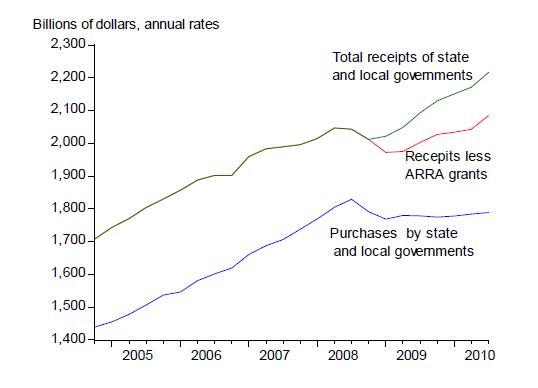

But when you look at what state and local governments did with the funds, you find that they did not increase purchases of goods and services or increase infrastructure projects. This is clearly demonstrated in the following chart showing state and local government receipts, with and without ARRA grants, and purchases of goods and services. Observe how total receipts of state and local governments increased sharply due to ARRA, much more than without ARRA.

But state and local government purchases have hardly increased at all and they are still below the levels of late 2008 before ARRA grants began.

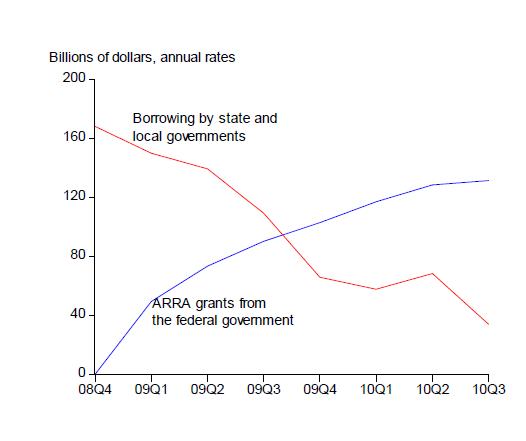

What did the states do with the ARRA funds? The data show that they mainly used the funds to reduce their borrowing, as shown clearly in the next graph. In addition, some of the funds went to increase government spending other than on purchases of goods and services, including transfer payments to individuals, mainly Medicaid. Such transfers are not considered “purchases” by the BEA and they only increase GDP to the extent that they lead to a net increase in purchases by governments or persons. As with the case of federal government purchases, the

debated over the size of the government purchases multiplier does not matter in this case because state and local government purchases did not increase as a result of ARRA.

Finally, consider the third component of ARRA: temporary payments to persons such as the one-time $250 checks sent in 2009, the refundable tax credits, or the temporary changes in withholding. The macroeconomic purpose of this component of ARRA was to jump-start personal consumption expenditures—a major part of GDP—and thereby jump-start GDP and the

economy.

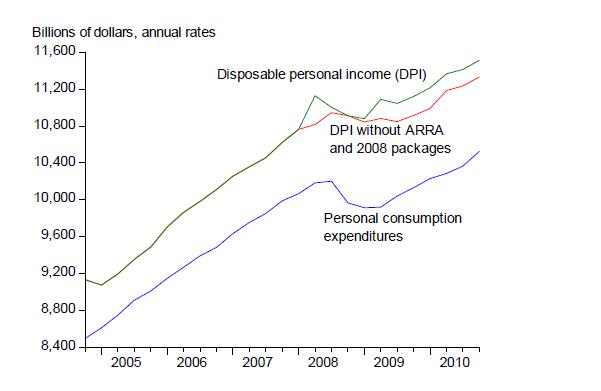

Here it is useful to consider the Stimulus Act of 2008 along with ARRA because both acts are similar in this dimension and occurred nearly back-to-back. In the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 checks were sent to people on a one-time basis and aggregate disposable personal income jumped dramatically though temporarily. In ARRA the amounts were initially smaller and more drawn out than the 2008 stimulus; though temporary, the increase in disposable personal income lasted through 2010.

Both cases are illustrated in the next chart which shows aggregate disposable personal income—with and without the stimulus payments—along with personal consumption expenditures from 2005 through 2010. Observe the increase in disposable income at the time of the 2008 stimulus and the 2009 stimulus.7 However, aggregate personal consumption 7 The increase is much more pronounced and visible graphically using monthly data as shown in Taylor (2009), but after a few months into ARRA, the BEA stopped tabulating monthly data and focused on the quarterly data summarized in the bar chart presented here. For better comparison with 2009 and 2010, therefore, quarterly data rather than monthly data in 2008 are presented in the chart.

Expenditures did not increase by much at the time of these sharp increases in stimulus payments. In general, the overall pattern of personal consumption expenditures seems to move closely with

disposable personal income without the addition of the stimulus funds, though the decline in consumption is greater than the decline in either measure of disposable personal income.

The relationship between the temporary stimulus payments versus the more permanent changes in income without the stimulus can be studied more rigorously than is possible in the above chart using regression techniques. These statistical techniques show that the effect of the temporary stimulus payments on personal consumption expenditures is much smaller than the effect of more permanent income changes and statistically insignificant from zero.8 This is what the permanent income theory and the life cycle theory of consumption would predict from such temporary payments. As in the case of the grants to the states the temporary payments were mainly added to personal saving in the form of reduced net borrowing. In effect the increased borrowing by the federal government to finance ARRA was nearly matched by a decrease in net borrowing by the state and local governments and by persons.

8 In a regression with correction for serial correlation over the period from 2000.1 to 2010.4 with personal consumption expenditures as the dependent variable, the coefficient on the temporary stimulus payments is 0.19 with a standard error of 0.14, while the coefficient on disposable personal income without the payments is 0.87 with a standard error of 0.05. If one separates out the 2009 stimulus, the coefficient on the temporary payments is still insignificantly different from zero and actually turns negative.

Fundamentals of Financial Management

ISBN: 978-0324597707

12th edition

Authors: Eugene F. Brigham, Joel F. Houston