Question: Write a summary about Using decision trees to aid decision-making in nursing AUTHORS Dawn Dowding, PhD, RN, is senior lecturer, Hull-York Medical School; Carl Thompson,

Write a summary about Using decision trees to aid decision-making in nursing AUTHORS Dawn Dowding, PhD, RN, is senior lecturer, Hull-York Medical School; Carl Thompson, DPhil, RN, is senior research fellow, Department of Health Sciences; both at University of York.

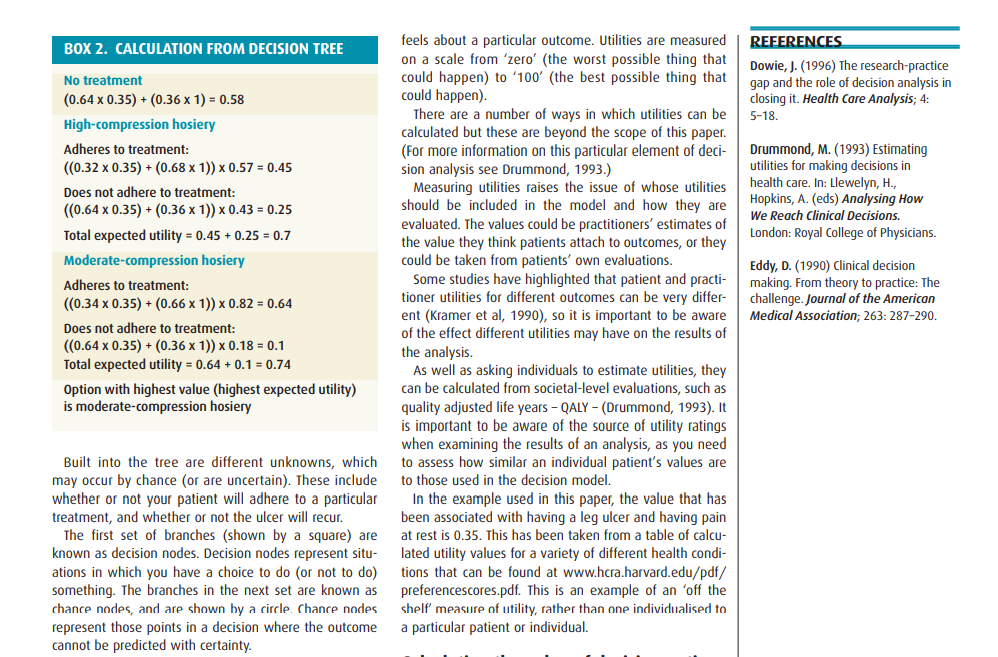

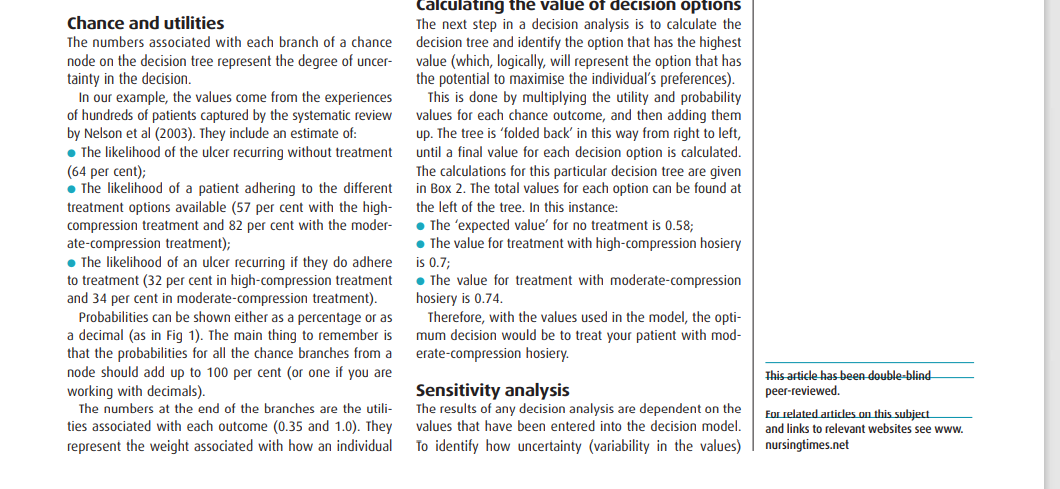

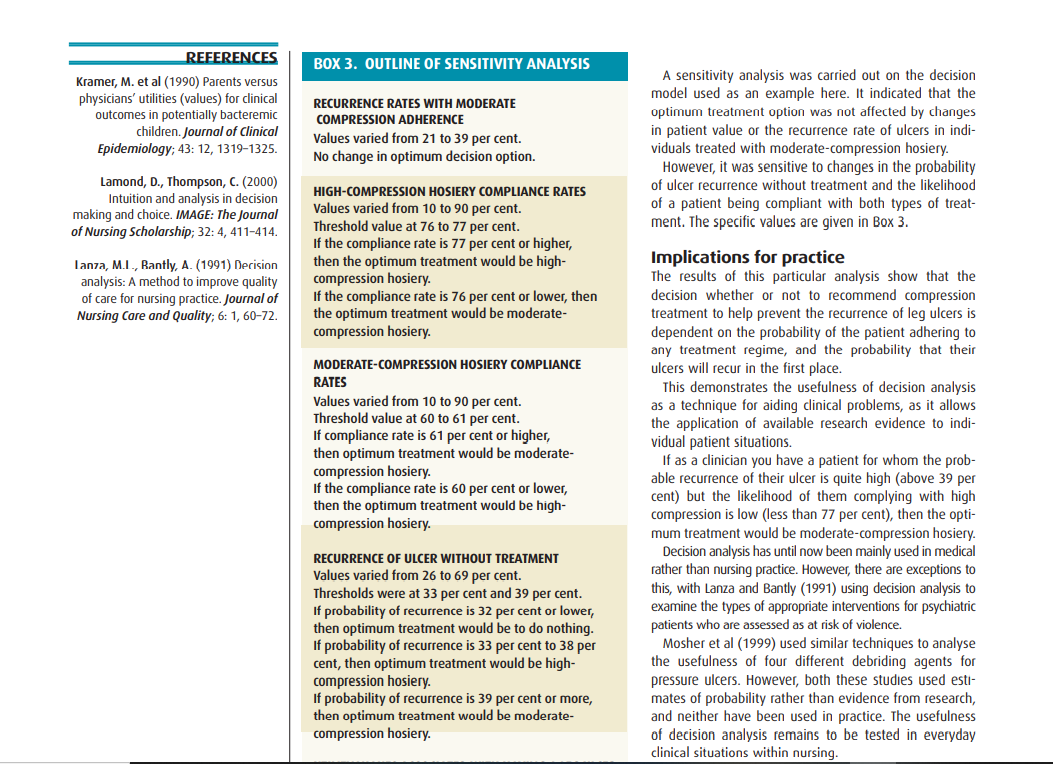

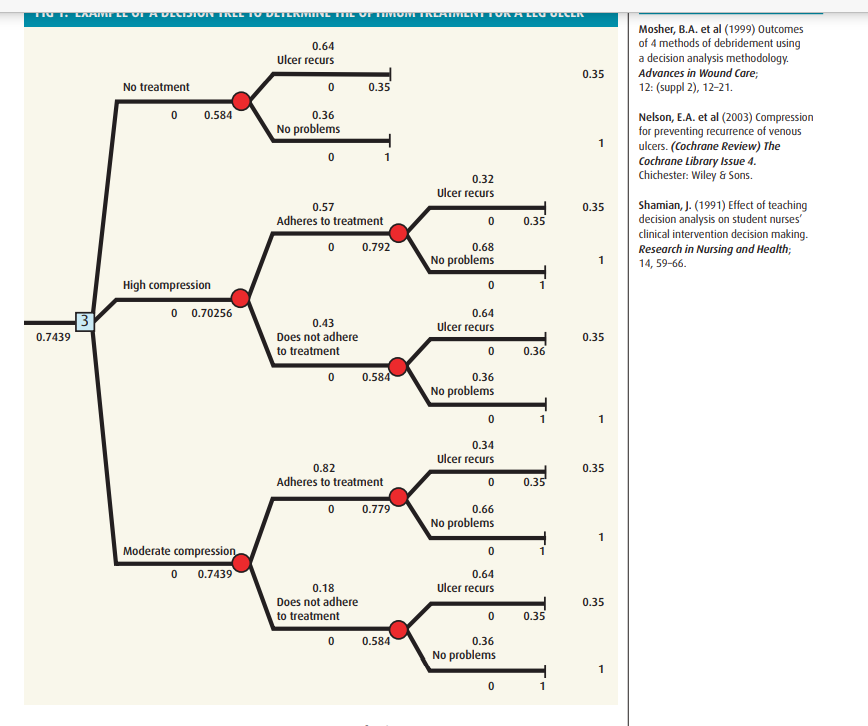

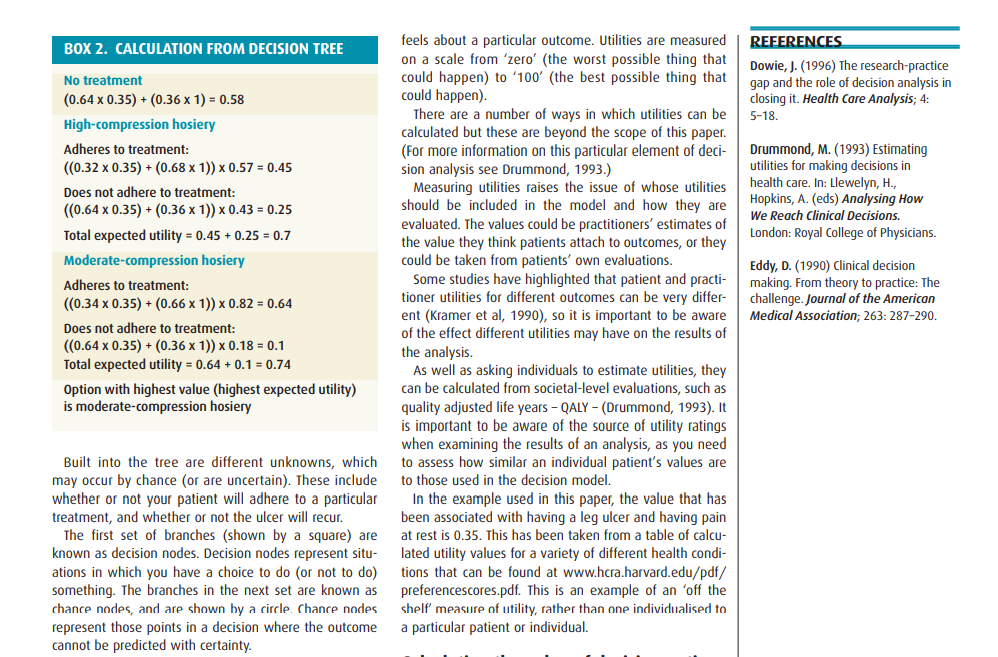

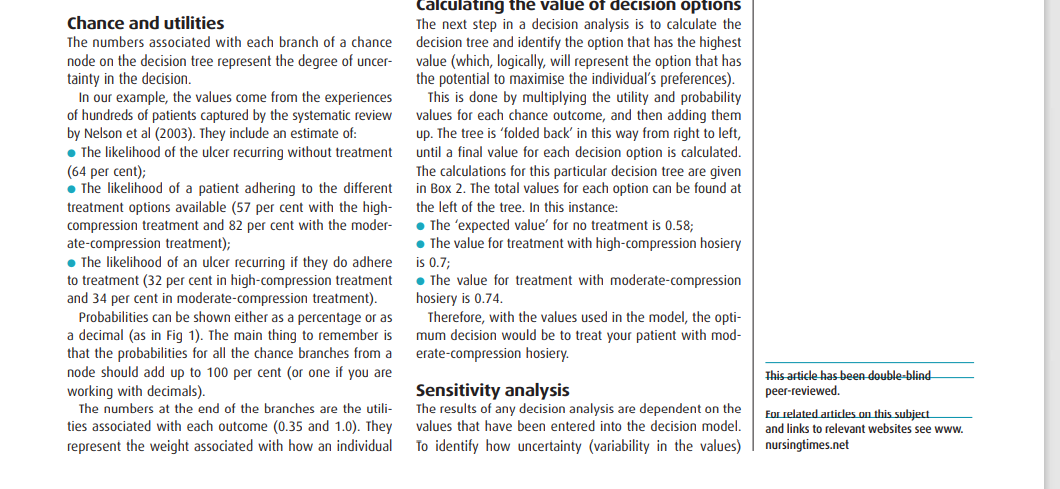

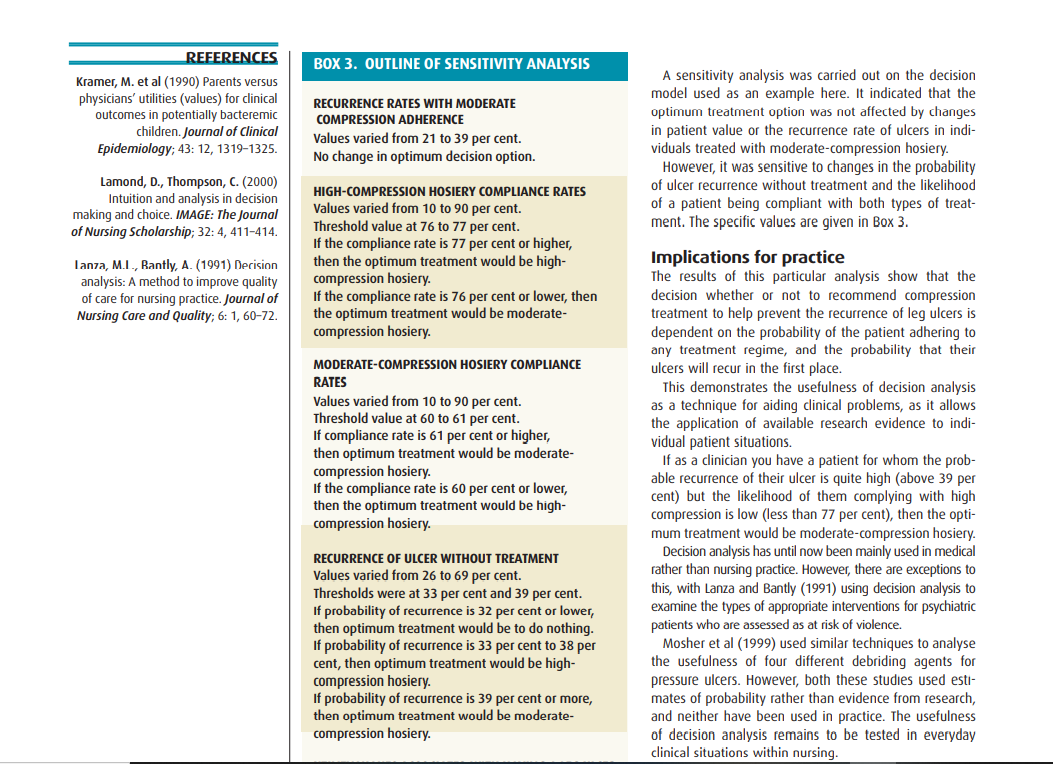

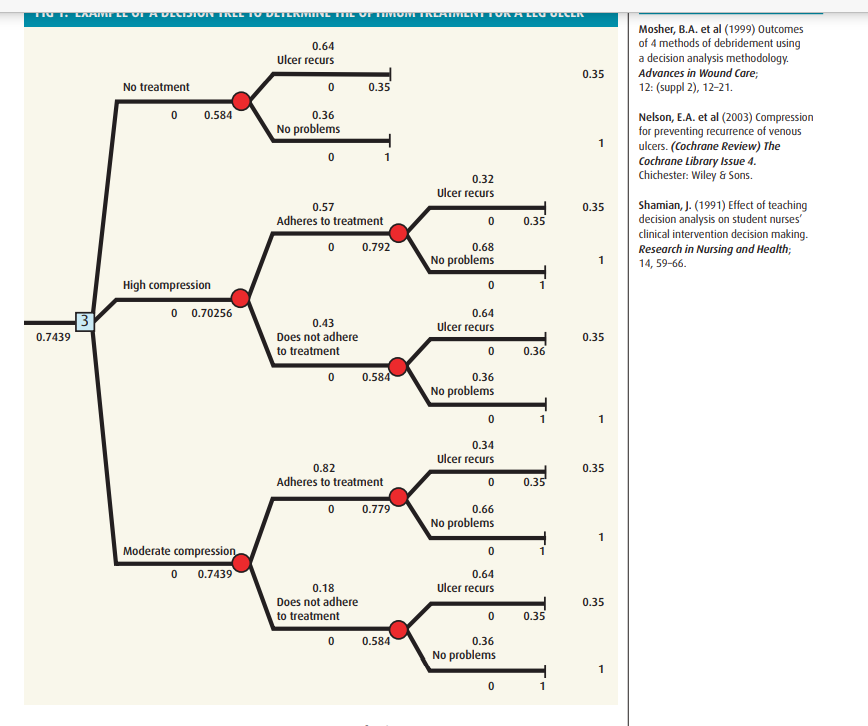

ADVANCED CLINICAL Using decision trees to aid decision-making in nursing AUTHORS Dawn Dowding, PhD, RN, is senior lecturer, Hull-York Medical School; Carl Thompson, DPhil, RN, is senior research fellow, Department of Health Sciences; both at University of York. ABSTRACT Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2004) Using decision trees to aid decision-making in nursing. Nursing Times; 100:21, 36-39. This article discusses judgement and decision-making in nursing. It outlines an approach to analysing clinical prob- lems known as decision analysis. It suggests decision analysis can be a useful technique for nurses to assist them with decision-making in practice. REFERENCES Balla, J.I. et al (1989) Obstacles to the acceptance of clinical decision analysis. British Medical Journal; 298: 579-582. In decision analysis, decision problems are normally constructed as a decision tree (Dowie, 1996). By structur- ing the problem in this way, and adding numerical values to the different branches, the problem can be analysed and the 'optimum' choice determined. The branches rep- resent both the probability (likelihood) of a particular outcome occurring and the value (utility) a decision- maker attaches to that outcome. One of the benefits of using a decision-analytic approach is the ability explicitly to integrate evidence from research with the choices you are considering (Dowding and Thompson, 2002). Often the probabilities used to inform decision models come from research evidence, and because you are using probabilities the degree of uncertainty associated with outcomes and choices is also clear. Therefore, for particu- lar types of decision problem - diagnostic and interven- tion-type decisions - decision analysis may be a useful way of helping clinicians make evidence-based decisions. Bell, D. et al (1988) Descriptive, normative and prescriptive interactions in decision making. In: Bell, D. et al (eds) Decision Making. Descriptive, Normative and Prescriptive Interactions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. This is the second of four papers that discuss judgement and decision-making in nursing. The first paper (Thompson et al, 2004) highlighted the importance of judgement and decision-making to nursing practice. The aim of this paper is to discuss how the complexity associated with making decisions can be made sense of using a structured approach called decision analysis. Decision analysis is particularly suitable for decisions where no one, single clear choice or action presents itself, and where the views of the decision maker(s) - often the patient-need to be informed by the possibility of different outcomes Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2002) Decision analysis. In: Thompson, C., Dowding, D. (eds) Clinical Decision Moking and Judgement in Nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Decision analysis in clinical practice The best way to explain how decision analysis works is to provide an example from clinical practice (Box 1). This is an example of a decision taken under conditions of uncertainty. In fact, almost all decisions in health care Cambridge University Press. Dowding, D., Thompson, C. (2002) Decision analysis. In: Thompson, C., Dowding, D. (eds) Clinical Decision Making and Judgement in Nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. decisions can be made sense of using a structured approach called decision analysis. Decision analysis is particularly suitable for decisions where no one, single clear choice or action presents itself, and where the views of the decision maker(s) - often the patient - need to be informed by the possibility of different outcomes (Dowding and Thompson, 2002). Decision analysis in clinical practice The best way to explain how decision analysis works is to provide an example from clinical practice (Box 1). This is an example of a decision taken under conditions of uncertainty. In fact, almost all decisions in health care take place in conditions of irreducible' uncertainty (Eddy, 1990). It is unclear whether or not the ulcer will recur and whether your patient would adhere to treatment even if you suggested it. The eventual decision may also depend on how the patient feels about the treatment as opposed to the possibility of developing another ulcer. What is decision analysis? Decision analysis is based on a theory of decision-making known as 'subjective expected utility theory' or SEU. SEU is a normative model of decision-making, meaning it describes the actions a decision-maker should take if she or he uses the available information logically and ration- ally. Briefly, the theory posits the notion that a decision- maker should choose the option with the highest probability of leading to an outcome matching her or his values or beliefs. This matching of outcomes to values is known as maximising expected utility (Bell et al, 1988). Structuring the decision Fig 1 shows a possible structure for this decision in the format of a decision tree. There are three possible choices: . To opt not to have any treatment; To have high compression hosiery; . To wear moderate-compression hosiery. BOX 1. DECISION ANALYSIS IN PRACTICE: USING COMPRESSION TO PREVENT LEG ULCER RECURRENCE You are a district nurse who has successfully treated one of your patients with a leg ulcer using compression bandaging. The ulcer has healed completely but you and the patient are worried it may recur. You think you have read somewhere that carrying on with compression treatment may help to stop the ulcer recurring, so via the National Electronic Library for Health (www.nelh.nhs.uk) you look on the Cochrane database and find a systematic review (Nelson et al, 2003). The review seems to suggest that treatment may be effective and highlights a number of treatments with different levels of compression. But you are also aware of how difficult your patient found it to stick to the compression bandage regime before. You would like discuss with her the benefits and limitations of having compression treatment, and find out how she feels about it. Perhaps, most of all, you want to include your patient in the decision-making process and for her to be an informed partner in, rather than a passive recipient of her care. REFERENCES BOX 2. CALCULATION FROM DECISION TREE No treatment Dowie, J. (1996) The research-practice gap and the role of decision analysis in closing it. Health Care Analysis; 4: 5-18 (0.64 x 0.35) + (0.36 x 1) = 0.58 High-compression hosiery Adheres to treatment: ((0.32 x 0.35) + (0.68 x 1)) x 0.57 = 0.45 Does not adhere to treatment: ((0.64 x 0.35) + (0.36 x 1)) x 0.43 = 0.25 Drummond, M. (1993) Estimating utilities for making decisions in health care. In: Llewelyn, H., Hopkins, A. (eds) Analysing How We Reach Clinical Decisions. London: Royal College of Physicians. Total expected utility = 0.45 + 0.25 = 0.7 Moderate-compression hosiery Adheres to treatment: (0.34 x 0.35) + (0.66 x 1)) > 0.82 = 0.64 Eddy, D. (1990) Clinical decision making. From theory to practice: The challenge. Journal of the American Medical Association; 263: 287-290. Does not adhere to treatment: (0.64 x 0.35) + (0.36 x 1)) x 0.18 = 0.1 Total expected utility = 0.64 +0.1 = 0.74 feels about a particular outcome. Utilities are measured on a scale from 'zero' (the worst possible thing that could happen to '100' (the best possible thing that could happen). There are a number of ways in which utilities can be calculated but these are beyond the scope of this paper. (For more information on this particular element of deci- sion analysis see Drummond, 1993.) Measuring utilities raises the issue of whose utilities should be included in the model and how they are evaluated. The values could be practitioners' estimates of the value they think patients attach to outcomes, or they could be taken from patients' own evaluations. Some studies have highlighted that patient and practi- tioner utilities for different outcomes can be very differ- ent (Kramer et al, 1990), so it is important to be aware of the effect different utilities may have on the results of the analysis. As well as asking individuals to estimate utilities, they can be calculated from societal-level evaluations, such as quality adjusted life years - QALY (Drummond, 1993). It is important to be aware of the source of utility ratings when examining the results of an analysis, as you need to assess how similar an individual patient's values are to those used in the decision model. In the example used in this paper, the value that has been associated with having a leg ulcer and having pain at rest is 0.35. This has been taken from a table of calcu- lated utility values for a variety of different health condi- tions that can be found at www.hcra.harvard.edu/pdf/ preferencescores.pdf. This is an example of an 'off the shelf' measure of utility, rather than one individualised to a particular patient or individual. Option with highest value (highest expected utility) is moderate-compression hosiery Built into the tree are different unknowns, which may occur by chance (or are uncertain). These include whether or not your patient will adhere to a particular treatment, and whether or not the ulcer will recur. The first set of branches (shown by a square) are known as decision nodes. Decision nodes represent situ- ations in which you have a choice to do or not to do) something. The branches in the next set are known as chance nodes, and are shown by a circle. Chance nodes represent those points in a decision where the outcome cannot be predicted with certainty. Chance and utilities The numbers associated with each branch of a chance node on the decision tree represent the degree of uncer- tainty in the decision In our example, the values come from the experiences of hundreds of patients captured by the systematic review by Nelson et al (2003). They include an estimate of: The likelihood of the ulcer recurring without treatment (64 per cent); The likelihood of a patient adhering to the different treatment options available (57 per cent with the high- compression treatment and 82 per cent with the moder- ate-compression treatment); The likelihood of an ulcer recurring if they do adhere to treatment (32 per cent in high-compression treatment and 34 per cent in moderate-compression treatment). Probabilities can be shown either as a percentage or as a decimal (as in Fig 1). The main thing to remember is that the probabilities for all the chance branches from a node should add up to 100 per cent (or one if you are working with decimals). The numbers at the end of the branches are the utili- ties associated with each outcome (0.35 and 1.0). They represent the weight associated with how an individual Calculating the value of decision options The next step in a decision analysis is to calculate the decision tree and identify the option that has the highest value (which, logically, will represent the option that has the potential to maximise the individual's preferences). This is done by multiplying the utility and probability values for each chance outcome, and then adding them up. The tree is 'folded back' in this way from right to left, until a final value for each decision option is calculated. The calculations for this particular decision tree are given in Box 2. The total values for each option can be found at the left of the tree. In this instance: The 'expected value' for no treatment is 0.58; . The value for treatment with high-compression hosiery is 0.7; The value for treatment with moderate-compression hosiery is 0.74 Therefore, with the values used in the model, the opti- mum decision would be to treat your patient with mod- erate-compression hosiery. This article has been double-blind peer-reviewed. Sensitivity analysis The results of any decision analysis are dependent on the values that have been entered into the decision model. To identify how uncertainty (variability in the values) For related articles on this subject and links to relevant websites see www. nursingtimes.net REFERENCES BOX 3. OUTLINE OF SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS Kramer, M. et al (1990) Parents versus physicians' utilities (values) for clinical outcomes in potentially bacteremic children. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; 43: 12, 1319-1325. RECURRENCE RATES WITH MODERATE COMPRESSION ADHERENCE Values varied from 21 to 39 per cent. No change in optimum decision option. A sensitivity analysis was carried out on the decision model used as an example here. It indicated that the optimum treatment option was not affected by changes in patient value or the recurrence rate of ulcers in indi- viduals treated with moderate-compression hosiery. However, it was sensitive to changes in the probability of ulcer recurrence without treatment and the likelihood of a patient being compliant with both types of treat- ment. The specific values are given in Box 3. Lamond, D., Thompson, C. (2000) Intuition and analysis in decision making and choice. IMAGE: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship; 32:4, 411-414. Lanza, M.L., Rantly, A. (1991) Decision analysis: A method to improve quality of care for nursing practice. Journal of Nursing Care and Quality; 6:1, 60-72. HIGH-COMPRESSION HOSIERY COMPLIANCE RATES Values varied from 10 to 90 per cent. Threshold value at 76 to 77 per cent. If the compliance rate is 77 per cent or higher, then the optimum treatment would be high- compression hosiery. If the compliance rate is 76 per cent or lower, then the optimum treatment would be moderate- compression hosiery. MODERATE-COMPRESSION HOSIERY COMPLIANCE RATES Values varied from 10 to 90 per cent. Threshold value at 60 to 61 per cent. If compliance rate is 61 per cent or higher, then optimum treatment would be moderate- compression hosiery. If the compliance rate is 60 per cent or lower, then the optimum treatment would be high- compression hosiery. Implications for practice The results of this particular analysis show that the decision whether or not to recommend compression treatment to help prevent the recurrence of leg ulcers is dependent on the probability of the patient adhering to any treatment regime, and the probability that their ulcers will recur in the first place. This demonstrates the usefulness of decision analysis as a technique for aiding clinical problems, as it allows the application of available research evidence to indi- vidual patient situations. If as a clinician you have a patient for whom the prob- able recurrence of their ulcer is quite high (above 39 per cent) but the likelihood of them complying with high compression is low (less than 77 per cent), then the opti- mum treatment would be moderate-compression hosiery. Decision analysis has until now been mainly used in medical rather than nursing practice. However, there are exceptions to this, with Lanza and Bantly (1991) using decision analysis to examine the types of appropriate interventions for psychiatric patients who are assessed as at risk of violence. Mosher et al (1999) used similar techniques to analyse the usefulness of four different debriding agents for pressure ulcers. However, both these studies used esti- mates of probability rather than evidence from research, and neither have been used in practice. The usefulness of decision analysis remains to be tested in everyday clinical situations within nursing. RECURRENCE OF ULCER WITHOUT TREATMENT Values varied from 26 to 69 per cent. Thresholds were at 33 per cent and 39 per cent. If probability of recurrence is 32 per cent or lower, then optimum treatment would be to do nothing. If probability of recurrence is 33 per cent to 38 per cent, then optimum treatment would be high- compression hosiery. If probability of recurrence is 39 per cent or more, then optimum treatment would be moderate- compression hosiery. dildiysis III evelyudy compics TICIY. clinical situations within nursing. UTILITY VALUES ASSOCIATED WITH HAVING A LEG ULCER Decision analysis has also been used as a teaching aid, Values varied from 0.1 to 0.9 with nursing students who had been taught to use clini- No change in optimum decision option. cal decision analysis making significantly better deci- sions (that is, they matched those of a group of experts) affects the resilts, calculation known as sensitivity than a control group (Shamian, 1991). analysis is often carried out. In this particular clinical situ- Decision analysis is not an appropriate technique to ation, there is uncertainty associated with the probability use for all problems found in nursing and midwifery of ulcers recurring without treatment - the Cochrane practice. It is suitable, however, for situations where review states that estimates range from 26 to 69 per cent (Dowding and Thompson, 2002): after 12 months - as well as some uncertainty associated There is a choice between alternative actions; with the likelihood of a patient complying with treatment. There is time to contemplate different alternatives; The patient may also have a different value associated .There is not one immediately right answer; with the possibility of living with a leg ulcer than that Patient views are important. used in this model. It is also a valuable tool for explicitly using research sensitivity analysis calculates what the optimum evidence to inform decision making. option would be in different decision contexts (repre- However, decision analysis is only as good as the sented by different values for different decision varia- assumptions that have been used to inform the model in bles, such as degree of compliance with treatment). the first place (Mosher et al, 1999), and it is reliant on It can then identify 'thresholds' where a change in the provision of accurate probability estimates. value results in a change in optimum treatment option If probabilities cannot be generated from research TIT. LAAIVIT EL VI AVLLIDTVI TILL TV VLTLITYINETTIL TIIVIIVI TILATIVILIVITVIA LLU VLCL 0.64 Ulcer recurs Mosher, B.A. et al (1999) Outcomes of 4 methods of debridement using a decision analysis methodology. Advances in Wound Care 12: (suppl 2), 12-21 0.35 No treatment 0 0.35 0 0.584 0.36 No problems 1 Nelson, E.A. et al (2003) Compression for preventing recurrence of venous ulcers. (Cochrane Review) The Cochrane Library Issue 4. Chichester: Wiley & Sons. 0.32 Ulcer recurs 0.35 0.57 Adheres to treatment 0 0.35 Shamian, J. (1991) Effect of teaching decision analysis on student nurses' clinical intervention decision making. Research in Nursing and Health 14,59-66. O 0.792 0.68 No problems 1 High compression 0 1 0 0.70256 0.64 Ulcer recurs 0.7439 0.43 Does not adhere to treatment 0.35 0.36 0 0.584 0.36 No problems 0 1 1 0.34 Ulcer recurs 0.35 0.82 Adheres to treatment 0 0.35 0 0.779 0.66 No problems 1 Moderate compression 0 0.7439 0.64 Ulcer recurs 0.18 Does not adhere to treatment 0.35 0 0.35 0 0.584 0.36 No problems 1 1 evidence, then often experts are asked to give their esti- Conclusion mates of the likelihood of events occurring. Decision analysis can be a useful technique for nurses. It These estimates can be subject to particular types of allows problematic decisions to be examined in detail, bias - an area that will be covered in the fourth paper in the use of research evidence to inform the decision, and this series. recommends optimum solutions in complex situations Assigning a numerical value to individuals' preferences where no right answer readily presents itself. Decision also causes some concern (Balla et al, 1989). analysis also promotes holistic care as patients and their However, one of the benefits of decision analysis as a carers have the opportunity of expressing how they technique is that it makes the assumptions inherent in would feel about receiving different treatment options. the decision process explicit, and therefore open to dis- By explicitly structuring the decision to be made in the cussion and debate. form of a tree, it is possible to identify exactly how and This is not the case with the other forms of decision why a particular decision was taken. This could provide a making, such as intuition, that are often used in nursing valuable basis for reflection on and discussions of clinical practice (Lamond and Thompson, 2000). decisions in nursing practice. SERIES ON CLINICAL DECISION-MAKING This is the second in a four-part series on decision-making: 1. Strategies for avoiding the pitfalls in clinical decision-making; 2. Using decision trees to structure clinical decisions; 3. How to use information 'cues' accurately when making clinical decisions; 4. Tools for handling information in clinical decision-making