Big Tech (for the purposes of this case) refers to Alphabet (which owns Google), Amazon, Apple, and

Question:

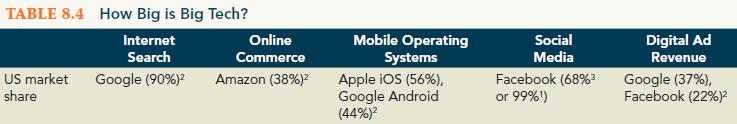

“Big Tech” (for the purposes of this case) refers to Alphabet (which owns Google), Amazon, Apple, and Facebook—the four firms being investigated by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) starting in February 2020. Table 8.4 shows how big they are. Collectively, these four firms plus Microsoft accounted for 18% of the stock market capitalization of the Standard & Poor’s 500 at the end of 2019. Starting in 2018, Apple was the first US firm to hit a $1 trillion capitalization, soon followed by Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft. Facebook is expected to follow.

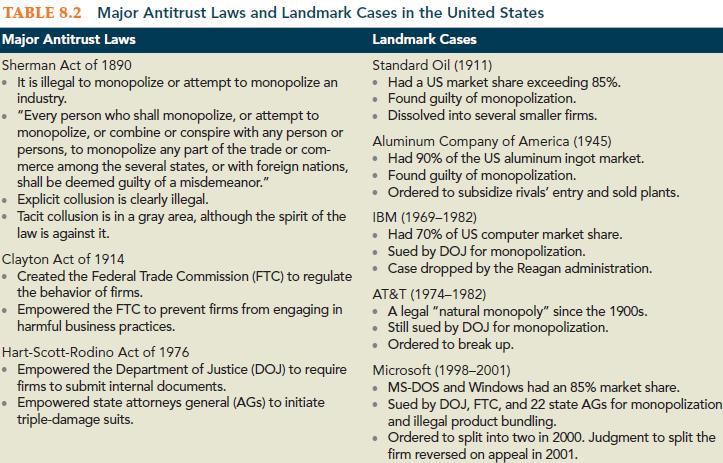

Starting with the 1890 enactment of the Sherman Act— the world’s first antitrust law—Americans have loved to hate big firms. A small army of antitrust enforcers in the two federal agencies—the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the FTC—as well as state attorney general’s offices work day in and day out to curb anticompetitive misconduct and challenge big “evil” firms, ranging from Standard Oil (1911) to Microsoft (1998–2001). “A lot of people wonder,” according to William Barr, the US attorney general during his January 2019 confirmation hearings, “how such huge behemoths that now exist in Silicon Valley have taken shape under the nose of the antitrust enforcers.” Recently, there is no shortage of loud voices calling for the antitrust agencies to wake up. Here are some headlines: “Should Digital Monopolies Be Broken Up?” (Economist, 2014), “Taming the Behemoths” (Fortune, 2018), “Antitrust Wall Street” (Bloomberg Businessweek, 2019), and “The Government v. the Tech Giants” (Wall Street Journal, 2019).

Antitrust is always controversial. After all, being big does not necessarily mean being bad. “Obtaining a monopoly by superior products, innovation, or business acumen is legal,” according to the FTC’s Guide to Antitrust Laws, “however, the same result achieved by exclusionary or predatory acts may raise antitrust concerns.” Politically, Big Tech seem to be a great punching bag for politicians to score points and attract votes. Socially, backlash against Big Tech has coined a new word: techlash. But legally, does the government have a case?

Picking targets, the antitrust community has focused neither on Amazon and Apple, which face formidable competitors, nor on Microsoft, which has been dealt with in a landmark case earlier (see Table 8.2). Google and Facebook are the top two targets for now. Since Google has been repeatedly fined by the European Commission the focus is now on Facebook, which has more than two billion users worldwide.

Facebook is free, but users willingly pay with data about themselves tracked by Facebook—a business model very similar to Google. In an influential article “The Antitrust Case Against Facebook,” Dina Srinivasan, an entrepreneur, argued that Facebook has engaged in a series of anticompetitive conduct that elbows out competitors and tricks customers to trust it. Founded in 2004, Facebook’s history is one that is constantly on the edge of violating user privacy. In the beginning, in competition with MySpace, Facebook promised that “We do not and will not use cookies to collect private information from any user.” It, thus, won numerous customers.

However, by 2007, Facebook had been publicly caught for tracking users. Facing an uproar, founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized and even promised to let users to vote on its privacy policy. Then in 2011, Facebook was again caught tracking users. It first claimed that the finding was a “bug” and then pleaded to users: “Please trust us . . . we don’t use our cookies to track you.” But in the same year, Facebook quietly obtained a patent “for a method . . . for tracking information about the activities of users of a social networking system while on another domain,” according to its patent registration. In 2011, it settled charges with the FTC regarding false statements regarding privacy policy.

In 2012, with more than a billion users and a record breaking IPO (a $104 billion market capitalization), Facebook discarded the results of a user referendum, whereby 88% of participating users voted against its proposed privacy changes. Its excuse was that for a binding referendum result, 30% of its one billion users would need to vote—per the rules it set by itself. Since only 589,000 users bothered to vote, the results were invalid. This was the end of “user democracy.” By 2014, with all competitors gone, Facebook’s monopoly was complete. It announced it would track users, even those who indicated “No, thanks.” According to Srinivasan, Facebook “would do precisely what it had spent seven years promising it did not and would not do, and finally accomplished what the previous competitive market had restrained it from doing.” Further, it demanded millions of websites that had signed up for Facebook plugins to change their privacy policy to extract from their users the consent to have Facebook track them. At the same time, Facebook was involved in a series of scandals, such as those associated with Cambridge Analytics’ abuse of user data and with alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election. Facing a mess, Zuckerberg was yanked to Congress for hearings in 2018 and 2020.

While Facebook is unpopular, has it violated antitrust laws? A leading challenge for antitrust enforcement is market definition. Critics argue that there is a blind spot in antitrust enforcers’ understanding of the nature of markets in which Facebook operates. A case in point is the 2012 unconditional clearance of the Facebook-Instagram merger. Antitrust enforcers first focused on the photo app (consumer) market. Since Facebook did not have a significant photo app, it was viewed not a serious competitor to Instagram. The second focus was on the advertising market. Because Instagram was earning no advertising revenue, it was found by antitrust enforcers to be a noncompetitor to Facebook. Having amassed 30 million users, Instagram was widely viewed by the media as one of Facebook’s most serious competitors. A second case is the 2014 unconditional clearance of the Facebook-WhatsApp merger. Again, Facebook’s motive to eliminate a viable competitor was so clear to the media but invisible to antitrust enforcers. How can these two mergers that according to critics have clear anticompetitive implications be cleared by the antitrust agencies? What is the problem?

The problem, according to Columbia law professor Tim Wu, is that Facebook (and Google and others) operate in a previously ignored market: the attention market. He made three points:

(1) Attention is scarce—limited by 168 hours every week.

(2) Attention cannot be stored or saved and must be consumed.

(3) Attention has value. Globally, more than $580 billion was spent on advertising every year (of which $200 billion in the United States). Viewed this way, Facebook is a leading-edge practitioner of “attention brokerage”—resale of attention to make money. As a finite resource, attention taken (measured in time) has economic value lost to consumers. “Sure, we may waste plenty of time as it is,” Wu wrote, “but at least it is ours to waste.” In this sense, taking away attention becomes the deprivation of a liberty, which has constitutional value. Facebook clearly understands the value of such attention. Despite promises to regulators that after the mergers, it would not pool user data with Instagram and WhatsApp, Facebook ended up doing exactly that—sharing data to better capture user attention via targeted ads. Using time spent as a proxy for attention, Wu estimated that Facebook had a 55% social media market share and Instagram 13%—a combined total of 68%.

Srinivisan estimated Facebook’s and Instagram’s market share to be 66% and 18%, respectively—a combined total of 84%. In comparison, using the number of users as a market, Srinivasan reported that 99% of US adults who use social media, representing two-thirds of all US adults, use Facebook.

Clearly, there is a lack of consensus on how to define the markets in which Facebook and other Big Tech firms operate. However, this has not prevented antitrust advocates from prescribing medicines:

(1) Break up Big Tech firms—and unwind some of the previously approved mergers such as Instagram and WhatsApp.

(2) Turn Big Tech firms such as Facebook and Google into regulated utilities and cap their prices and return on capital.

(3) Constrain their growth by preventing them from acquiring smaller rivals.

Although unpopular, Big Tech have many defenders. Breaking up the crown jewel of American capitalism carries a national-security risk in light of heightened strategic competition with China. Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent would love to see the wings of their global rivals clipped. Turning Big Tech into utilities will definitely cripple their incentive to innovate. Constraining their growth simply may not work.

Two decades after the “successful” antitrust case against Microsoft (which escaped from being broken up on appeal), Microsoft’s browser market share increased from 85% in 2000 to more than 90% now. More philosophically, anti-antitrust authors ask whether trustbusting is “really about protecting consumers or merely about expanding the power of government.” In their view, competition will take care of the Big Tech problem. Antitrust represents “the grotesque contradiction of attempting to preserve the freedom of the market by government controls—to preserve the benefits of laissez-faire by abrogating it.” The last point was not written by a fringe author. It was penned by Alan Greenspan, who served as chair of the Federal Reserve (1987–2006). As the debate rages, next time when you start Facebook, can you spare a thought on this debate?

CASE DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. ON ETHICS: From an antitrust standpoint, do Big Tech (in particular Facebook) represent a problem?

2. ON ETHICS: If you believe Facebook represents a problem that can be (at least partially) solved by antitrust actions, what would be your recommendations?

3. ON ETHICS: As CEO of the leading firm in a traditional industry (such as meat packing or shoemaking) with a 60% market share, do you think Big Tech’s market share to be too large that would justify antitrust actions?

Step by Step Answer: