Question: 2) What SCM processes could have been put in place to ensure the second contamination of carmoisine did not occur? Contamination in the Bulk Agri-Commodity

2) What SCM processes could have been put in place to ensure the second contamination of carmoisine did not occur?

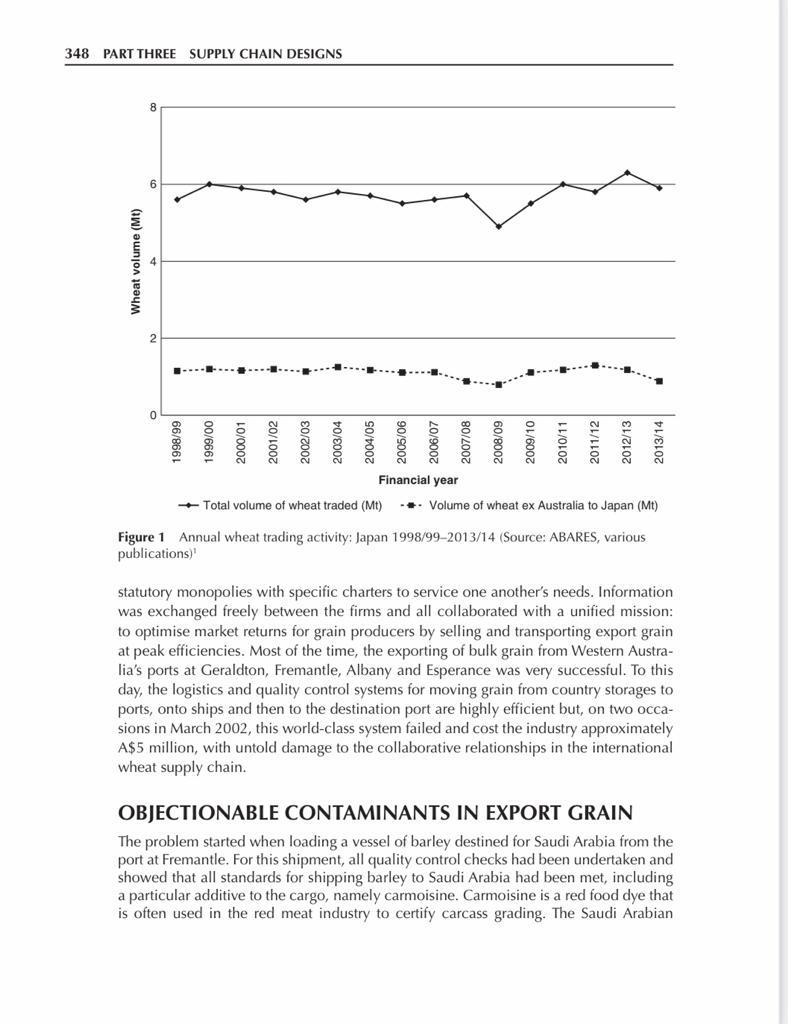

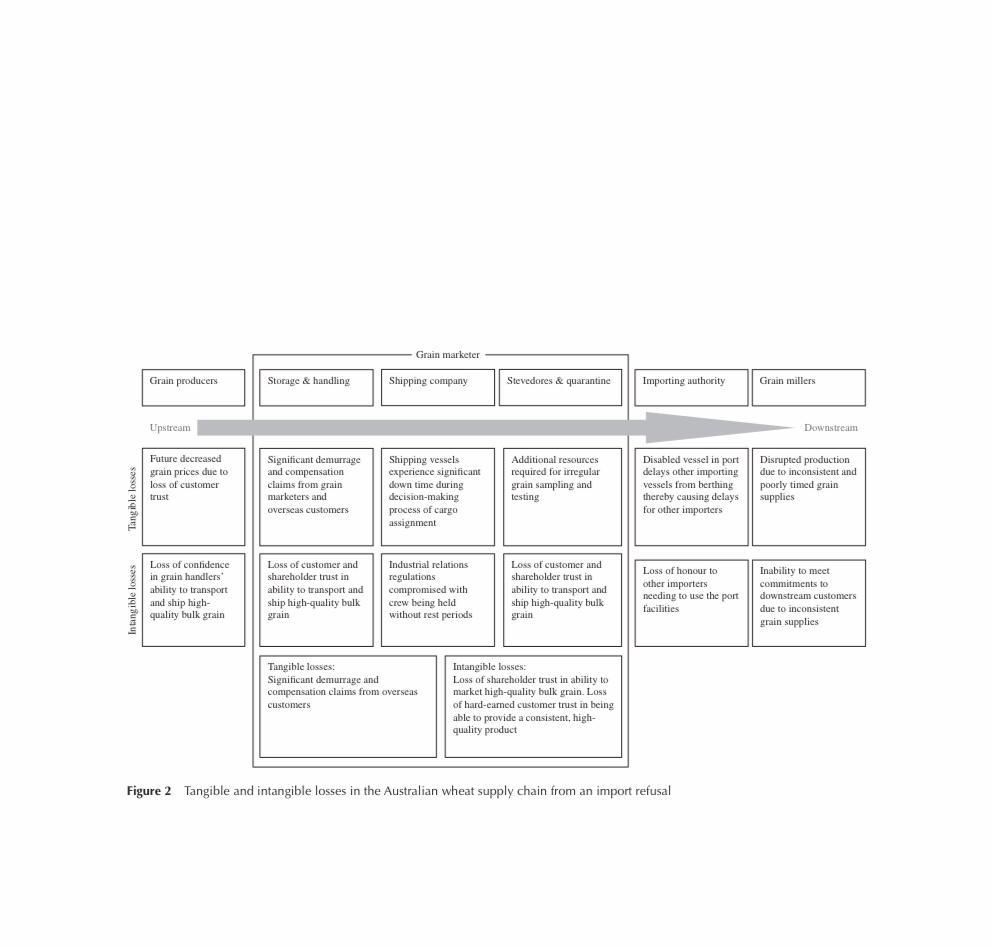

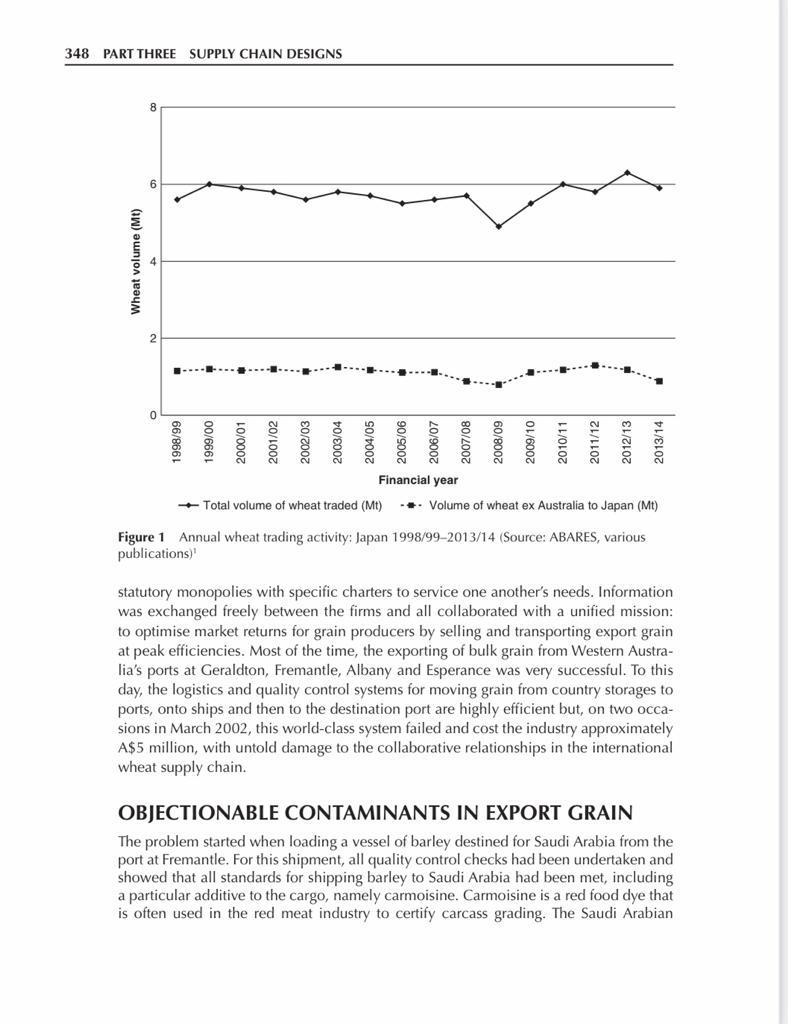

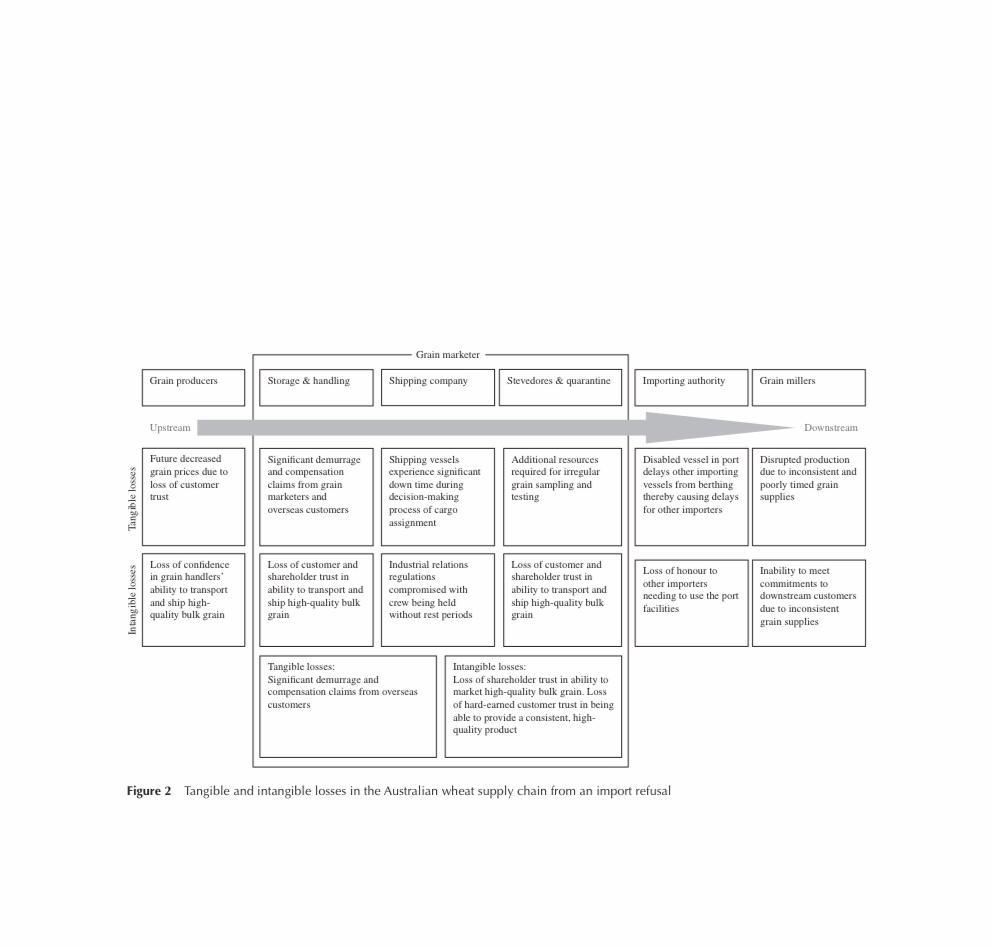

Contamination in the Bulk Agri-Commodity Logistics Chain Elizabeth Jackson Royal Veterinary College TRADING RELATIONS BETWEEN WESTERN AUSTRALIA AND JAPAN Japan imports 5-6 million tonnes of bulk wheat each year to manufacture products such as udon noodles, bread, cake, Chinese noodles, white salted noodles, spaghetti, instant noodles and beer. Each year, Western Australia ships nearly 1.5 million tonnes of bulk grain to Japan, with the income from wheat for noodle production alone estimated to have a value of A$150 million to the local economy. While Japan buys a significant amount of wheat from Western Australia, it is also the largest market for other bulk agri- commodities, such as barley, oats, canola and cereal hay, thereby indicating the impor- tance of the trade relationship between the two nations. The Japanese market for Australian wheat is relatively stable, although Australia only supplies Japan with about a fifth of its demand (Figure 1), so market competition with suppliers such as Canada and the US is a key concern for Australia. As a consequence, a great deal of care is needed for managing and maintaining this high-value commodity supply chain. To add to this, market relations in the Japanese context are largely based on trust, honour and long-term relationships between supply chain actors, which makes establishing and main- taining markets a delicate and complex task. AN OVERVIEW OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN EXPORT GRAIN INDUSTRY From 1933 to the beginning of the new millennium, Western Australian's grain export industry, which accounts for 95% of the state's annual harvest, was highly regulated with each sector of the supply chain operating as a government statutory authority. The ports, railways, quarantine services, grain traders and grain handlers all operated as 348 PART THREE SUPPLY CHAIN DESIGNS Wheat volume (Mt) ----- 66/8661 1999/00 2000/01 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 2004/05 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 Financial year Total volume of wheat traded (Mt) ... Volume of wheat ex Australia to Japan (Mt) Figure 1 Annual wheat trading activity: Japan 1998/99-2013/14 (Source: ABARES, various publications) statutory monopolies with specific charters to service one another's needs. Information was exchanged freely between the firms and all collaborated with a unified mission: to optimise market returns for grain producers by selling and transporting export grain at peak efficiencies. Most of the time, the exporting of bulk grain from Western Austra- lia's ports at Geraldton, Fremantle, Albany and Esperance was very successful. To this day, the logistics and quality control systems for moving grain from country storages to ports, onto ships and then to the destination port are highly efficient but, on two occa- sions in March 2002, this world-class system failed and cost the industry approximately A$5 million, with untold damage to the collaborative relationships in the international wheat supply chain. OBJECTIONABLE CONTAMINANTS IN EXPORT GRAIN The problem started when loading a vessel of barley destined for Saudi Arabia from the port at Fremantle. For this shipment, all quality control checks had been undertaken and showed that all standards for shipping barley to Saudi Arabia had been met, including a particular additive to the cargo, namely carmoisine. Carmoisine is a red food dye that is often used in the red meat industry to certify carcass grading. The Saudi Arabian CASE STUDIES CONTAMINATION IN THE BULK AGRI-COMMODITY LOGISTICS CHAIN 349 market demands that about 1% of all imported grain is coloured with carmoisine in an attempt to minimise black market grain trading. The colouring process is carried out at the time of loading bulk grain onto the ship destined for Saudi Arabia. The liquid food dye is slowly dripped onto the conveyor belt that is loading the grain onto the ship. After the shipment of barley left for Saudi Arabia, the next ship to be loaded at the port of Fremantle was high-value noodle wheat bound for Japan. As per standard practice, all quality checks were undertaken, the vessel was loaded and set sail. Once the vessel reached its destination in Japan in early March 2002, unloading commenced and local authorities began their stringent import checks, during which they identified an 'objec- tionable contaminant' in the cargo - this is one of the most serious claims that can be made about a cargo of food. Western Australia's most important Japanese customers were horrified by this finding and contacted the grain marketing agent immediately to express their outrage about the unacceptable condition of the cargo. Upon rigorous testing of the grain samples, it was found that the objectionable contaminant was traces of grain that had been treated with carmoisine. Unloading the vessel was ceased and the ship was to be berthed until the problem was resolved. The allegation of the carmoisine-contaminated cargo had the Western Australia grain industry in turmoil: valuable customers had been disappointed, an entire cargo of premium-quality wheat was split between the ship and port storage, the Japanese port had ceased operations, thereby preventing other vessels from berthing, extraordinary demur- rage costs were being incurred from the ship being left idle and there was a threat of the customers demanding monetary compensation for loss of earnings. Western Australian grain marketers found it perplexing that their Japanese customers should find miniscule traces of a food dye so unacceptable, particularly because it was an additive that another customer (Saudi Arabia) demanded as a standard treatment. After identifying the immedi- ate problem, substantial cracks started to appear in the seemingly robust supply chain. OBJECTIONABLE CONTAMINANT: CARMOISINE Objectionable contaminants in bulk grain commodities are usually traces of poisonous or dangerous substances such as pesticides, traces of herbicides used in crop manage- ment, traces of fertiliser from previous handling equipment, rust or paint flakes from inside the hold of a vessel, small pieces of metal from handling machinery, bird or rodent droppings from unclean storage facilities, poisonous gases from antiquated stor- age facilities or fungal mycotoxins produced during the growth or storage of wheat crops. International food standards specify a nil tolerance of generic objectionable con- taminants (such as those listed above), but individual markets also specify particular substances as objectionable. In Japan, Canada, the US, Norway and Sweden, carmois- ine is banned, based on evidence that it is linked to hyperactivity in children and hence is regarded as an objectionable contaminant in food importing. The confirmation that the objectionable contaminant found in the wheat cargo was carmoisine resulted in the entire cargo being rejected by Japan. This left the cargo of high-quality grain split between the port and the vessel, and without an owner. The 350 PART THREE SUPPLY CHAIN DESIGNS grain marketer eventually found a new buyer for the cargo at an enormous financial cost but the most significant operational cost was finding a way to return the part-unloaded cargo onto the ship. Japan is principally an importing nation so its port infrastructure has world-class facilities for unloading ships but very few, if any, facilities for loading ships. So reloading a bulk commodity onto a bulk vessel proved extremely costly in terms of emergency engineering and demurrage expenses. The reverse is true for Western Australia's bulk commodity ports, which are principally for exporting goods, so return- ing the cargo to its home port was out of the question, hence the need for the grain marketer to make a quick sale of the redundant cargo. When the matter was closed, the grain marketer responsible for selling the wheat and the bulk handler responsible for assembling and loading the cargo realised how depend- ent they were on one another to work collaboratively in protecting Japan as a valued customer. Relations between the two firms had been pushed to the limit with both blaming each other for the losses suffered: the grain marketer being blamed for not clearly communicating the fine detail of the exporting contract and the bulk handler being blamed for being so careless with assembling and loading the cargo (essentially not ensuring that all traces of carmoisine had been cleaned from the port's conveyor systems). Nevertheless, the relationship was recovered for the benefit of maintaining the important trade between Western Australia and its Japanese customer. The relationship with the Japanese customers had also been severely tested over this incident and the Japanese still had a sceptical view of Western Australia, even after relations had appeared to be mended. However, this situation was to worsen. The media was informed on 22 March 2002 that a 20,000 Mt cargo of noodle wheat had been rejected by Japan owing to contamination with carmoisine. This was the second cargo to be rejected within a month for the same reason. This second incident was almost too much for the Japanese to bear. They were furious that the promises that had been made regarding ship and handling hygiene had not been taken seriously. They considered that trust had been abused and that they had been dishonoured. As a consequence, two vital aspects of conducting business with Japan had been neglected - twice. At this point, grain pro- ducer lobbying groups had become involved with concerns about the breakdown of relations with Japan as a major buyer of their wheat. Fortunately, the Japanese were savvy enough to have not unloaded the second cargo before testing it for traces of carmoisine, so the operational losses experienced when the first cargo was rejected were not experienced to the same extent. Nevertheless, signifi- cant demurrage costs were incurred while a new buyer was sought for the second contaminated cargo. IMPORT REFUSALS AROUND THE WORLD Incidents of import refusals, like those cargoes rejected by the Japanese noodle wheat market, are costly terms of financial losses (tangible) and damaged supply chain relationships (intangible). Figure 2 illustrates the tangible and intangible losses experi- enced at each tier of the supply chain as a result of an import refusal. Grain marketer Grain producers Storage & handling & Shipping company Stevedores & quarantine Importing authority Grain millers Upstream Downstream Future decreased grain prices due to loss of customer Tangible losses Significant demurrage and compensation claims from grain marketers and Shipping vessels experience significant down time during decision-making process of cargo assignment Additional resources required for irregular grain sampling and testing Disabled vessel in port delays other importing vessels from berthing thereby causing delays for other importers Disrupted production due to inconsistent and poorly timed grain supplies trust overseas customers Intangible losses Loss of confidence in grain handlers ability to transport and ship high- quality bulk grain Loss of customer and shareholder trust in ability to transport and ship high-quality bulk grain Industrial relations regulations compromised with crew being held without rest periods Loss of customer and shareholder trust in ability to transport and ship high-quality bulk grain Loss of honour to other importers needing to use the port facilities Inability to meet commitments to downstream customers due to inconsistent grain supplies Tangible losses: Significant demurrage and compensation claims from overseas customers Intangible losses: Loss of shareholder trust in ability to market high-quality bulk grain. Loss of hard-earned customer trust in being able to provide a consistent, high- quality product Figure 2 Tangible and intangible losses in the Australian wheat supply chain from an import refusal 352 PART THREE SUPPLY CHAIN DESIGNS Published research on the frequency of cargo rejections from Australia and elsewhere is extremely sparse as data of this kind can be commercially sensitive and are often only collected internally by marketing and handling organisations. This type of information is also very difficult to collect simply based on how to define a cargo rejection or import refusal. It is rare for a cargo to be rejected outright, like the Japanese noodle wheat cargo. It is much more common for 'near misses' to occur. This is when a mistake is corrected before any operational losses are incurred or financial losses are experienced (as a result of compensation claims from cargoes that are accepted but fall short of some quality standard). Despite the difficulty of measuring shipping rejections, the US Food and Drug Administration has been collecting high-quality data on food import refusals for over 10 years. While their data show that US import refusals of whole grain, milled grain prod- ucts and starch are extremely low (1.4% of refusals between 1998 and 2004), research- ers who have analysed the data agree that refusals of any imported goods have a negative impact on trade relations. In the case of Japan's refusal of contaminated Western Australian noodle wheat, the trade ramifications were significant. The trusted relation- ship between Australia's largest grain-producing state and a long-term, high-value customer was damaged, not to mention the animosity caused between the various members of the grain supply chain within Western Australia. Essentially, the harmony within a long-established supply chain was temporarily destroyed. CONCLUSION In March 2002, the Western Australian grain supply chain suffered a desperate shock to its system with two consecutive cargoes of noodle wheat being rejected by Japan because of contamination from the food dye carmoisine. Relationships between actors in the supply chain were stretched to the limit. The Japanese demanded answers about the quality of the cargoes, and supply chain actors were looking for compensation for the loss of income they experienced. At the same time, further upstream, grain produc- ers were worried about losing a valuable downstream customer. It was not only rela- tionships that were tested; this case also provides an interesting insight into how sophisticated port infrastructures have become rigid in terms of optimising efficiency whereby irregular occurrences such as these turn out to be unmanageable. The out- comes of these incidents were that the Western Australian grain industry had suffered a substantial economic loss and relations between numerous members of the grain sup- ply chain and some of its customers had been severely damaged - damage that only hard, collaborative work could repair. This case has shed light on the importance of port efficiencies and demonstrated that, despite the complexity of the global grain supply chain, relations between supply chain actors are at the heart of successfully managing such chains. The fact remains that the trade of agricultural commodities fluctuates as a consequence of numerous factors, such as global seasonal conditions, erratic currency markets and changes to govern- ment import/export regulations. Japan's Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries has a highly regulated method of buying wheat for the nation's milling industry, which