Question: Case Study: Question: A. How did Jean-Claude Biver attempt to change the Swiss watch industry? B. What factors account for Bivers success at Blancpain and

Case Study:

Question:

A. How did Jean-Claude Biver attempt to change the Swiss watch industry?

B. What factors account for Bivers success at Blancpain and Omega? What professional and personal challenges did he face?

C. How would you assess Biver as a leader?

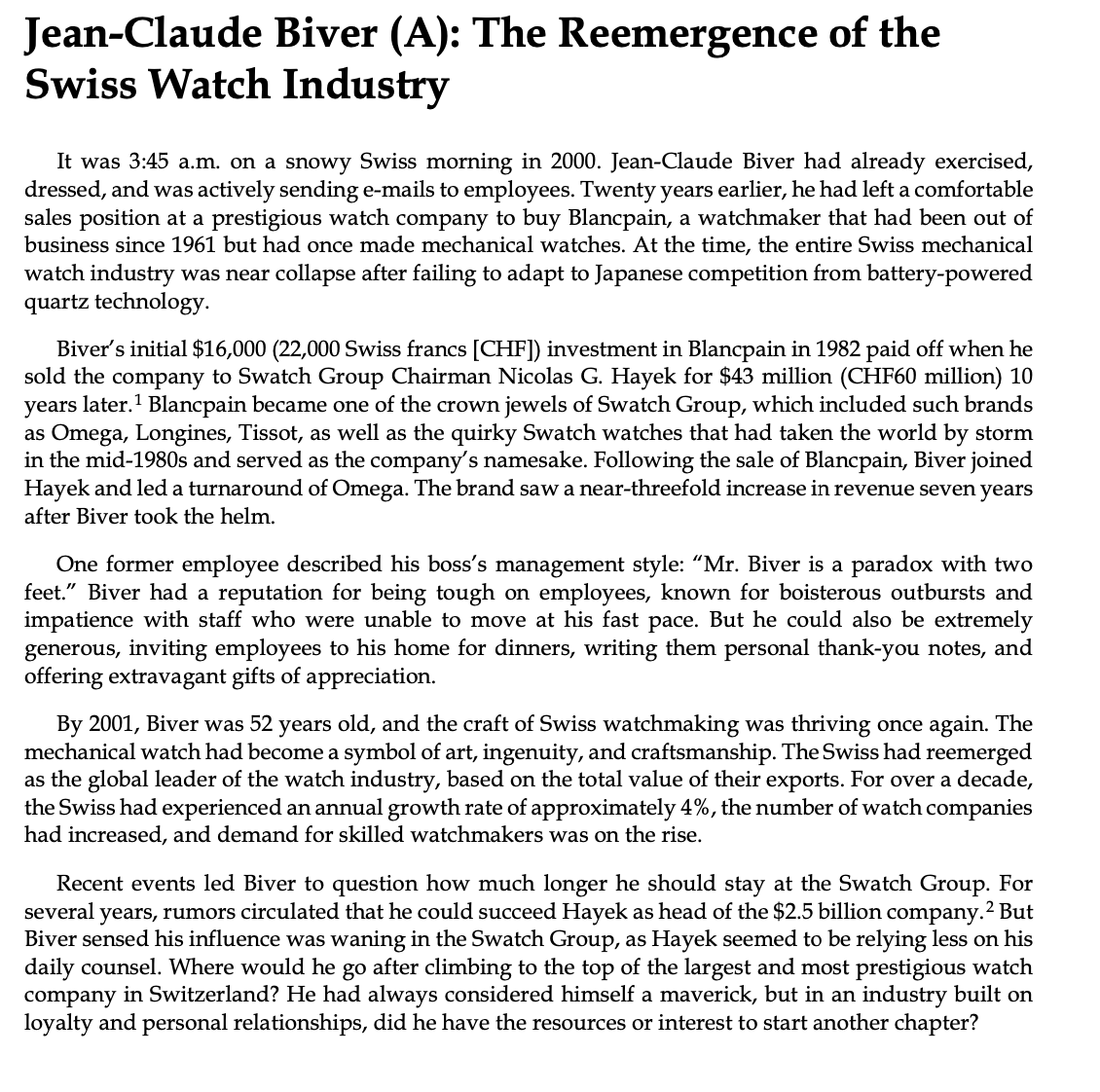

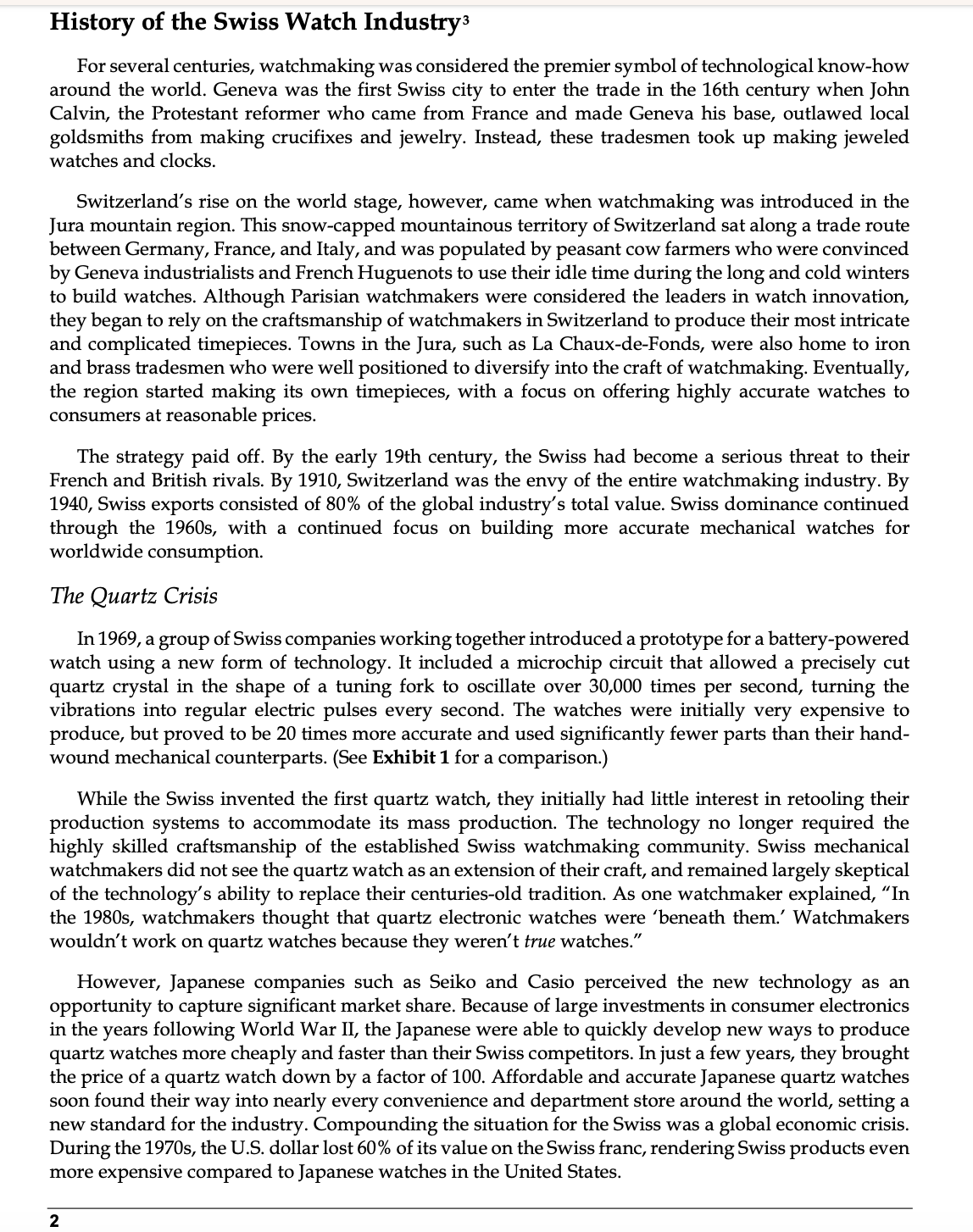

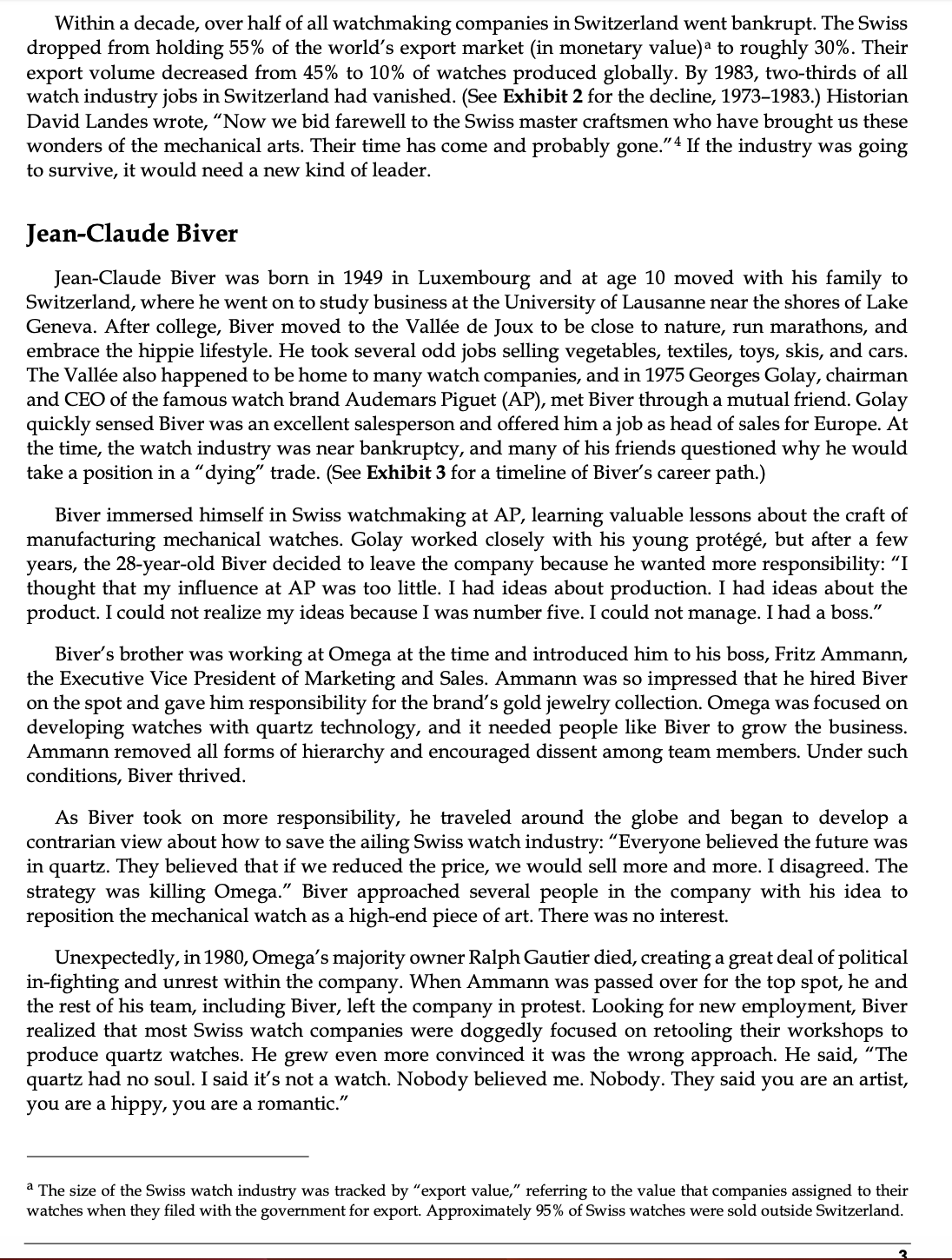

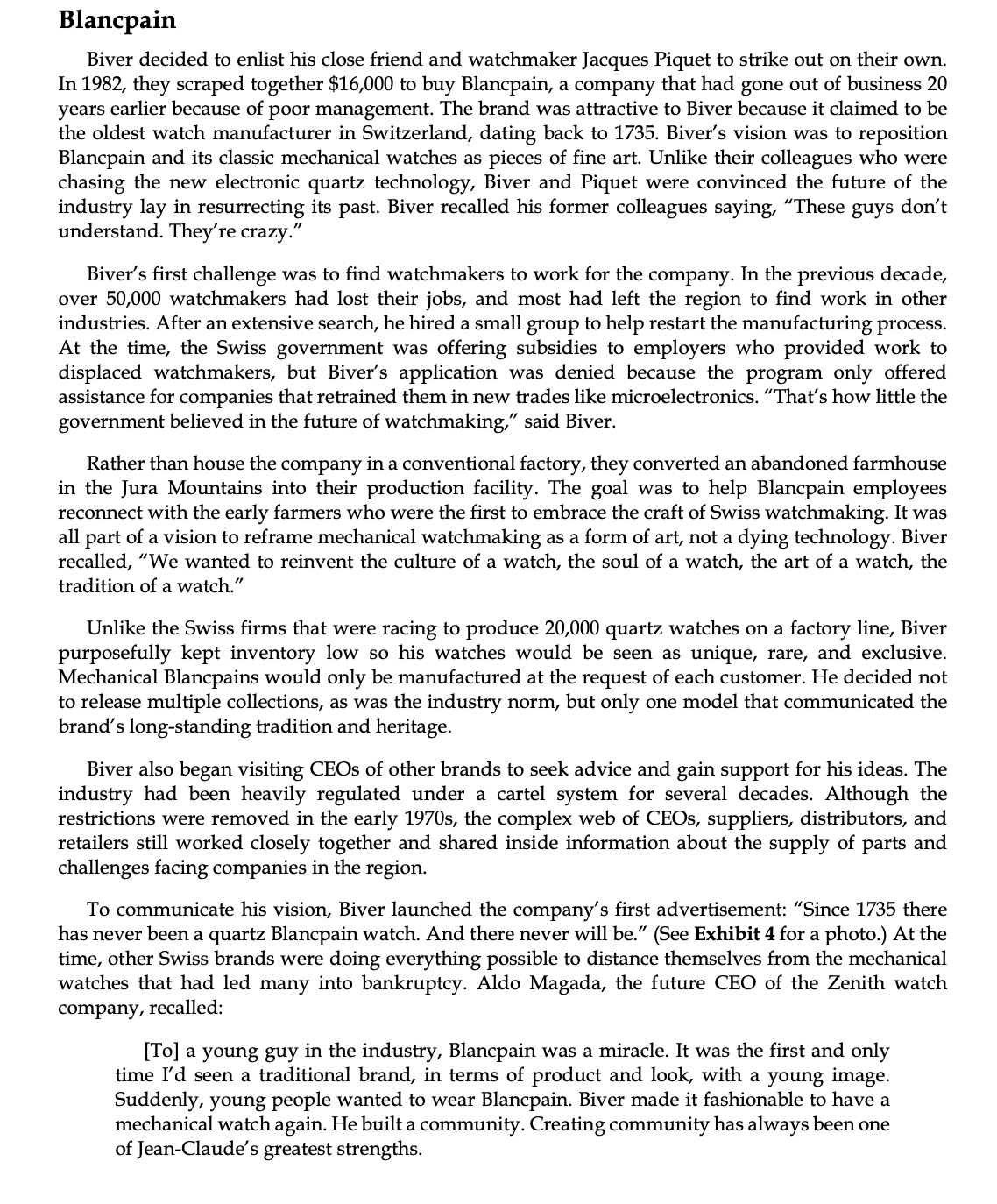

Jean-Claude Biver (A): The Reemergence of the Swiss Watch Industry It was 3:45 a.m. on a snowy Swiss morning in 2000. Jean-Claude Biver had already exercised, dressed, and was actively sending e-mails to employees. Twenty years earlier, he had left a comfortable sales position at a prestigious watch company to buy Blancpain, a watchmaker that had been out of business since 1961 but had once made mechanical watches. At the time, the entire Swiss mechanical watch industry was near collapse after failing to adapt to Japanese competition from battery-powered quartz technology. Biver's initial $16,000 (22,000 Swiss francs [CHF]) investment in Blancpain in 1982 paid off when he sold the company to Swatch Group Chairman Nicolas G. Hayek for \$43 million (CHF60 million) 10 years later. 1 Blancpain became one of the crown jewels of Swatch Group, which included such brands as Omega, Longines, Tissot, as well as the quirky Swatch watches that had taken the world by storm in the mid-1980s and served as the company's namesake. Following the sale of Blancpain, Biver joined Hayek and led a turnaround of Omega. The brand saw a near-threefold increase in revenue seven years after Biver took the helm. One former employee described his boss's management style: "Mr. Biver is a paradox with two feet." Biver had a reputation for being tough on employees, known for boisterous outbursts and impatience with staff who were unable to move at his fast pace. But he could also be extremely generous, inviting employees to his home for dinners, writing them personal thank-you notes, and offering extravagant gifts of appreciation. By 2001, Biver was 52 years old, and the craft of Swiss watchmaking was thriving once again. The mechanical watch had become a symbol of art, ingenuity, and craftsmanship. The Swiss had reemerged as the global leader of the watch industry, based on the total value of their exports. For over a decade, the Swiss had experienced an annual growth rate of approximately 4%, the number of watch companies had increased, and demand for skilled watchmakers was on the rise. Recent events led Biver to question how much longer he should stay at the Swatch Group. For several years, rumors circulated that he could succeed Hayek as head of the $2.5 billion company. 2 But Biver sensed his influence was waning in the Swatch Group, as Hayek seemed to be relying less on his daily counsel. Where would he go after climbing to the top of the largest and most prestigious watch company in Switzerland? He had always considered himself a maverick, but in an industry built on loyalty and personal relationships, did he have the resources or interest to start another chapter? History of the Swiss Watch Industry 3 For several centuries, watchmaking was considered the premier symbol of technological know-how around the world. Geneva was the first Swiss city to enter the trade in the 16th century when John Calvin, the Protestant reformer who came from France and made Geneva his base, outlawed local goldsmiths from making crucifixes and jewelry. Instead, these tradesmen took up making jeweled watches and clocks. Switzerland's rise on the world stage, however, came when watchmaking was introduced in the Jura mountain region. This snow-capped mountainous territory of Switzerland sat along a trade route between Germany, France, and Italy, and was populated by peasant cow farmers who were convinced by Geneva industrialists and French Huguenots to use their idle time during the long and cold winters to build watches. Although Parisian watchmakers were considered the leaders in watch innovation, they began to rely on the craftsmanship of watchmakers in Switzerland to produce their most intricate and complicated timepieces. Towns in the Jura, such as La Chaux-de-Fonds, were also home to iron and brass tradesmen who were well positioned to diversify into the craft of watchmaking. Eventually, the region started making its own timepieces, with a focus on offering highly accurate watches to consumers at reasonable prices. The strategy paid off. By the early 19th century, the Swiss had become a serious threat to their French and British rivals. By 1910, Switzerland was the envy of the entire watchmaking industry. By 1940 , Swiss exports consisted of 80% of the global industry's total value. Swiss dominance continued through the 1960s, with a continued focus on building more accurate mechanical watches for worldwide consumption. The Quartz Crisis In 1969 , a group of Swiss companies working together introduced a prototype for a battery-powered watch using a new form of technology. It included a microchip circuit that allowed a precisely cut quartz crystal in the shape of a tuning fork to oscillate over 30,000 times per second, turning the vibrations into regular electric pulses every second. The watches were initially very expensive to produce, but proved to be 20 times more accurate and used significantly fewer parts than their handwound mechanical counterparts. (See Exhibit 1 for a comparison.) While the Swiss invented the first quartz watch, they initially had little interest in retooling their production systems to accommodate its mass production. The technology no longer required the highly skilled craftsmanship of the established Swiss watchmaking community. Swiss mechanical watchmakers did not see the quartz watch as an extension of their craft, and remained largely skeptical of the technology's ability to replace their centuries-old tradition. As one watchmaker explained, "In the 1980s, watchmakers thought that quartz electronic watches were 'beneath them.' Watchmakers wouldn't work on quartz watches because they weren't true watches." However, Japanese companies such as Seiko and Casio perceived the new technology as an opportunity to capture significant market share. Because of large investments in consumer electronics in the years following World War II, the Japanese were able to quickly develop new ways to produce quartz watches more cheaply and faster than their Swiss competitors. In just a few years, they brought the price of a quartz watch down by a factor of 100 . Affordable and accurate Japanese quartz watches soon found their way into nearly every convenience and department store around the world, setting a new standard for the industry. Compounding the situation for the Swiss was a global economic crisis. During the 1970s, the U.S. dollar lost 60% of its value on the Swiss franc, rendering Swiss products even more expensive compared to Japanese watches in the United States. 2 Within a decade, over half of all watchmaking companies in Switzerland went bankrupt. The Swiss dropped from holding 55% of the world's export market (in monetary value) to roughly 30%. Their export volume decreased from 45% to 10% of watches produced globally. By 1983 , two-thirds of all watch industry jobs in Switzerland had vanished. (See Exhibit 2 for the decline, 1973-1983.) Historian David Landes wrote, "Now we bid farewell to the Swiss master craftsmen who have brought us these wonders of the mechanical arts. Their time has come and probably gone." 4 If the industry was going to survive, it would need a new kind of leader. Jean-Claude Biver Jean-Claude Biver was born in 1949 in Luxembourg and at age 10 moved with his family to Switzerland, where he went on to study business at the University of Lausanne near the shores of Lake Geneva. After college, Biver moved to the Valle de Joux to be close to nature, run marathons, and embrace the hippie lifestyle. He took several odd jobs selling vegetables, textiles, toys, skis, and cars. The Valle also happened to be home to many watch companies, and in 1975 Georges Golay, chairman and CEO of the famous watch brand Audemars Piguet (AP), met Biver through a mutual friend. Golay quickly sensed Biver was an excellent salesperson and offered him a job as head of sales for Europe. At the time, the watch industry was near bankruptcy, and many of his friends questioned why he would take a position in a "dying" trade. (See Exhibit 3 for a timeline of Biver's career path.) Biver immersed himself in Swiss watchmaking at AP, learning valuable lessons about the craft of manufacturing mechanical watches. Golay worked closely with his young protg, but after a few years, the 28-year-old Biver decided to leave the company because he wanted more responsibility: "I thought that my influence at AP was too little. I had ideas about production. I had ideas about the product. I could not realize my ideas because I was number five. I could not manage. I had a boss." Biver's brother was working at Omega at the time and introduced him to his boss, Fritz Ammann, the Executive Vice President of Marketing and Sales. Ammann was so impressed that he hired Biver on the spot and gave him responsibility for the brand's gold jewelry collection. Omega was focused on developing watches with quartz technology, and it needed people like Biver to grow the business. Ammann removed all forms of hierarchy and encouraged dissent among team members. Under such conditions, Biver thrived. As Biver took on more responsibility, he traveled around the globe and began to develop a contrarian view about how to save the ailing Swiss watch industry: "Everyone believed the future was in quartz. They believed that if we reduced the price, we would sell more and more. I disagreed. The strategy was killing Omega." Biver approached several people in the company with his idea to reposition the mechanical watch as a high-end piece of art. There was no interest. Unexpectedly, in 1980, Omega's majority owner Ralph Gautier died, creating a great deal of political in-fighting and unrest within the company. When Ammann was passed over for the top spot, he and the rest of his team, including Biver, left the company in protest. Looking for new employment, Biver realized that most Swiss watch companies were doggedly focused on retooling their workshops to produce quartz watches. He grew even more convinced it was the wrong approach. He said, "The quartz had no soul. I said it's not a watch. Nobody believed me. Nobody. They said you are an artist, you are a hippy, you are a romantic." a The size of the Swiss watch industry was tracked by "export value," referring to the value that companies assigned to their watches when they filed with the government for export. Approximately 95% of Swiss watches were sold outside Switzerland. Blancpain Biver decided to enlist his close friend and watchmaker Jacques Piquet to strike out on their own. In 1982 , they scraped together $16,000 to buy Blancpain, a company that had gone out of business 20 years earlier because of poor management. The brand was attractive to Biver because it claimed to be the oldest watch manufacturer in Switzerland, dating back to 1735. Biver's vision was to reposition Blancpain and its classic mechanical watches as pieces of fine art. Unlike their colleagues who were chasing the new electronic quartz technology, Biver and Piquet were convinced the future of the industry lay in resurrecting its past. Biver recalled his former colleagues saying, "These guys don't understand. They're crazy." Biver's first challenge was to find watchmakers to work for the company. In the previous decade, over 50,000 watchmakers had lost their jobs, and most had left the region to find work in other industries. After an extensive search, he hired a small group to help restart the manufacturing process. At the time, the Swiss government was offering subsidies to employers who provided work to displaced watchmakers, but Biver's application was denied because the program only offered assistance for companies that retrained them in new trades like microelectronics. "That's how little the government believed in the future of watchmaking," said Biver. Rather than house the company in a conventional factory, they converted an abandoned farmhouse in the Jura Mountains into their production facility. The goal was to help Blancpain employees reconnect with the early farmers who were the first to embrace the craft of Swiss watchmaking. It was all part of a vision to reframe mechanical watchmaking as a form of art, not a dying technology. Biver recalled, "We wanted to reinvent the culture of a watch, the soul of a watch, the art of a watch, the tradition of a watch." Unlike the Swiss firms that were racing to produce 20,000 quartz watches on a factory line, Biver purposefully kept inventory low so his watches would be seen as unique, rare, and exclusive. Mechanical Blancpains would only be manufactured at the request of each customer. He decided not to release multiple collections, as was the industry norm, but only one model that communicated the brand's long-standing tradition and heritage. Biver also began visiting CEOs of other brands to seek advice and gain support for his ideas. The industry had been heavily regulated under a cartel system for several decades. Although the restrictions were removed in the early 1970s, the complex web of CEOs, suppliers, distributors, and retailers still worked closely together and shared inside information about the supply of parts and challenges facing companies in the region. To communicate his vision, Biver launched the company's first advertisement: "Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be." (See Exhibit 4 for a photo.) At the time, other Swiss brands were doing everything possible to distance themselves from the mechanical watches that had led many into bankruptcy. Aldo Magada, the future CEO of the Zenith watch company, recalled: [To] a young guy in the industry, Blancpain was a miracle. It was the first and only time I'd seen a traditional brand, in terms of product and look, with a young image. Suddenly, young people wanted to wear Blancpain. Biver made it fashionable to have a mechanical watch again. He built a community. Creating community has always been one of Jean-Claude's greatest strengths. Within its first year, Blancpain sold 97 watches and collected revenues of $75,000. Five years later, it was selling 3,000 watches per year with $9.4 million in annual revenue. Biver continued to share his ideas with other CEOs and enlist support from key Swiss watch industry associations and employee unions. Displaced watchmakers who had refused to adapt to quartz technology flooded Blancpain with job applications. Taking notice, many other brands like Ebel and Breitling also started to reposition their mechanical watches in a similar fashion. Biver's Early Leadership Style As Blancpain expanded, Biver needed to build his team. Philippe Peverelli, an early Blancpain employee, recalled his mother getting an unexpected call from Biver after her son failed to respond to Biver's informal job offer at a dinner party. "Hello, Ms. Peverelli," said Biver. "I own a watch company. I made an offer to your son for a job. I don't know if you have been in charge of the education of Philippe, but I do not want to congratulate you because he's a very rude and non-educated person." Embarrassed, Peverelli's mother demanded her son meet with Biver at the suggested time, 5:00 a.m. the next morning. Within 30 minutes, Biver had convinced Peverelli to abandon his career in the hospitality industry and join Blancpain. "My family and friends thought I was crazy to join a watch company. But it was the beginning of a fantastic experience," said Peverelli, who later became CEO of Tudor watches. "Biver gave me my passion for the watchmaking industry. He can transmit passion for everything." To many, Biver's leadership style was an oxymoron. He could be loud, aggressive, and impatient. His temper could also flare, especially when employees made mistakes or delivered bad news. Once he became so upset with his secretary that he plunged a Montblanc fountain pen into her desk, breaking the pen and covering her with ink. Biver walked back to his office, while she stood there crying. One employee commented, "He was the worst HR manager I had ever met. He must have threatened to fire me 100 times." Biver himself admitted: When starting Blancpain I felt alone. I didn't have any confidence, and so I got angry when someone on my team didn't do the right job. I was traveling between meetings in a Volkswagen camping bus because I could not afford to sleep in a hotel. I would put a dime in the railway station shower to get 3 minutes of water. It didn't give me much tranquility. And so I would get angry because I had no security. I did not trust myself. On the other hand, Biver regularly invited employees to go running in the mountains with him before work, hosted dinners in his home to celebrate their important life events, and was always the first person to share credit for the company's success by writing generous bonus checks. By the late 1980s, Blancpain had grown to over 100 people; to thank his employees for their work, Biver arranged for an all-expenses-paid weeklong vacation in Italy for all the watchmakers and their families. When they returned, the employees were so touched by their boss's generosity that they decided to work five extra Sundays without pay to make up for the lost production time. A Personal Crisis As Biver reached his late 30 s, life seemed to be all he could have imagined. Then suddenly his wife announced she wanted to end their marriage. Biver recalled the disastrous effect it had on him: I believed it was the end of the world. I stopped coming in at 4:00 in the morning. I used my money for excessive parties. I brought girlfriends into the office. I was totally breaking. It was typical behavior for a guy who is not in harmony with himself. Biver's lawyer, who was also a close personal friend, finally warned Biver that he was destroying Blancpain. Biver recounted the lawyer's stern advice: "You don't come to work, or you arrive at 11:00 in a Ferrari. This is very bad, compared to your watchmakers." The lawyer gave Biver an ultimatum "You need to change your attitude or sell the company." Biver weighed his options. Given the success of Blancpain, it would certainly command top dollar if he chose to sell. Recently, Nicolas G. Hayek, the chairman of the Swatch Group, had expressed interest in adding more watch brands to his growing portfolio after the success he had had launching the Swatch watch in 1983. Moreover, demand for mechanical watches appeared to be reemerging. Watch collectors had started buying vintage watches at auction for record prices. Many CEOs took notice and refocused their efforts on reviving their mechanical production lines. Biver decided to sell Blancpain to Hayek in 1992 and was offered a seat on the Swatch Group board. The company that Biver had paid $16,000 for in 1982 sold for $43 million a decade later. Seller's Remorse? Following the sale, Biver jumped on a flight from Switzerland to Hawaii. While sitting on the beach, he began to question his decision, thinking, "Biver, you now have millions, but you are an idiot alone here in Hawaii. You are the poorest rich man in the world." From his five-star hotel room, Biver called Hayek and said he wanted to work for him. Hayek asked why Biver would possibly want to return after just selling his company. Biver responded, "I realize I just sold my soul. I sold my passion. I sold my people. I treated people like merchandise. One hundred and ten people worked for me and they built Blancpain." Hayek agreed to let Biver come back to Blancpain, under the condition that he would also be given responsibility to turn Omega around. Biver was relieved. But how could he face his former employees? Would they accept him, especially since they knew how much money he had made on the sale? Also, could he have a boss again? Was he ready to navigate the politics inside such a large organization? The Swatch Group Hayek, a Lebanese-born management consultant, was hired by several Swiss bankers during the 1970s "Quartz Crisis" to examine several failing watch companies that had become insolvent. He issued a scathing report, with recommendations for massive industry consolidation and new leadership. The banks had no interest in overseeing a lengthy restructuring effort and offered to sell a majority stake to Hayek. He agreed and formed a new holding company, Socit de Microlectronique et d'Horlogerie (later renamed "Swatch Group"), which included brands such as Tissot, RADO, Longines, and Omega. Hayek's vision was to implement a revolutionary new business strategy where production efficiencies could be spread across multiple brands under one common "Group." In 1983, Hayek's team also launched the Swatch watch as a response to Japanese mass-market competition. Driven by quartz technology, the colorful Swatches sold at prices low enough so that consumers were encouraged to treat them as fashion accessories: "Swatch = second watch, or Swiss watch." A runaway hit, by the late 1980s, over 50 million Swatches had been produced and sold. The product injected significant liquidity into the Swatch Group and, more importantly, confidence back into the entire Swiss watch industry. Hayek now hoped to extend the reach of the high-end mechanical watch brands within the Swatch Group. The acquisition of Blancpain meant he could compete with brands like Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin, whose watches could range well over $10,000. But he also hoped to resuscitate Omega and compete head-on with Rolex in the $2,500 to $5,000 range. (See Exhibit 5 for the industry's structure.) Whereas the rest of the Swatch Group was focused on the mass production of Tissot, RADO, Longines, and Swatch watches, Omega continued to struggle to regain market share. Hayek saw Biver as the solution. Joining the Swatch Group and Turning around Omega Biver reported directly to Hayek, sitting alongside several other brand presidents. Early on, he found ways to engage Hayek, purposefully sparring with him about ideas after board meetings and spending time outside of work together. "Hayek was the boss, period. He was my master," said Biver. "But if you are close to the boss and the boss gives you the keys, then you can drive the car. I was probably the only one that understood him 100%. I was the only one who shared his vision." One of Biver's first tasks was to develop a new vision and message for Omega and help those inside the organization buy into it. As the first watch worn by astronauts on the moon, Omega employees were very proud of their brand's rich heritage. But recently, its previous managers had chased the mass market by lowering prices and introducing multiple product lines that diluted Omega's identity. At Blancpain, Biver had learned the importance of creating a coherent vision. During lunches with employees, he would often draw a bike wheel on the back of a napkin to explain his management philosophy with Omega employees: If all the spokes are same length, the wheel will create energy and turn. Everything must start from the middle. If it starts from me, it's nonsense. It must start from the center, and the center is your message. The vision defines all our actions, from the receptionist all the way up. Biver also enlisted outsiders to communicate and refresh Omega's relevance. He introduced the concept of having brand ambassadors promote products, extending their involvement beyond typical television product placements or celebrity advertisements in magazines. In the mid-1990s, he convinced supermodel and business mogul Cindy Crawford to sign with the brand and help re-launch the Omega Constellation as a women's fashion watch throughout the world. (See Exhibit 4.) Crawford recalled her initial impressions of Biver's vision: We felt like our brands aligned. It was about quality and timelessness. Typically, models would be hired for one advertising campaign and that would be it. But JeanClaude understood the importance of developing a long-term mutual commitment. Early on he asked if I would tour the factories so he could share his passion for the art of watchmaking with me. It was clear he had such a sense of passion and creativity. He was fearless. As a result, it never felt like work. In parallel, Biver partnered with MGM Studios and the James Bond movie franchise to revive the Omega Seamaster line for men. He traveled to every country where a new Bond movie was released to publicize the brand. Biver used the opportunity to seek input from watch aficionados around the world, hoping to build new communities of Omega collectors. Managing His Team Within the Swatch Group, Biver was seen as a brilliant, but sometimes imposing, individual. He tested people early, and if they did not meet his high standards, he would often refuse to meet with them again. According to Valrie Servageon, a marketing executive at Omega: He could shift from having a big smile on his face and a contagious laugh into someone with very precise and pointed questions. If you were not confident about what you were doing, it could be a challenge. He'd yell and the walls would tremble. People would tremble. At first, I thought he was just a crazy person. But then I would go back to my desk and realize his ideas were genius. Jean-Frederic Dufour, who worked for Biver at Swatch Group, recalled an instance when Biver publicly berated him for mismanaging a client at an important industry conference. Later, Biver called Dufour into his office to apologize for the outburst. With tears in his eyes, Biver said, "You know I never met a guy like you in the watch industry. You're like my son and when I look at you, I see me." Now the CEO of Rolex, Dufour said, "Mr. Biver is very transparent with his thoughts and emotions. He had a very bad reputation as a manager within Swatch Group, but those of us who worked for him knew he was an excellent leader." While some people found Biver's style too aggressive, there were others who were eager to work with him. He only surrounded himself with people who he could engage in heated debate. A longtime employee said, "Biver nourishes himself with dialogue." Those who reported to Biver believed any idea they could clear through their boss had merit. For the first time in two decades, Omega sales were trending upward. Between 1995 and 1999, revenues increased from $350 million to over $900 million. 5 The Swatch Group also experienced record growth. (See Exhibit 6 for financials.) More broadly, the Swiss watch industry was booming, achieving a more than threefold increase in export value since its near collapse in the early 1980 s. 6 Across Switzerland, several competitor watch groups emerged to capitalize on the new demand for mechanical watches. Many old Swiss brands were being resuscitated, similar to what Biver had done for Blancpain. Looking Ahead In mid-2000, Biver learned he had contracted a severe case of Legionnaires' disease, leaving him unable to work. The infection nearly killed him. Later that year, he also learned that his second wife was expecting a son. Before getting ill, rumors had started to spread across the industry that Biver could likely succeed Hayek as head of Swatch Group. However, he felt that his influence with Hayek might be fading. "I had so much respect for Hayek, but could sense he was gently pushing me away," said Biver. Biver and Hayek agreed in 2001 that he would take a one-year sabbatical to fully recover and spend time with his family. While away, a close friend mentioned that Hublot, a small but respected watch brand, was having difficulty. Biver wanted to learn more about the company, known for its avantgarde watches with rubber straps. He approached the founder and owner, Carlo Crocco, about selling the company or possibly forming a partnership. Crocco appeared hesitant. The independently wealthy owner had heard rumors about Biver's infamous management style and was not sure if he would be a good fit for his watchmaking company. In the months that followed, Biver contemplated what might lie ahead. Should he go back to the Swatch Group? With $2.5 billion (CHF4.2 billion) in annual revenues, 18 brands, and over 20,000 employees, it was now the largest and most prestigious watch company in the world. Alternatively, given Biver's past success, he could retire wealthy and enjoy his growing family. Or was it worth considering something new, like Hublot? If so, was he interested in leading a company with 20 employees that was losing $2.5 million a year? Aldo Magada, a former Swatch Group executive and Biver protg, recalled, "It was the first time I had the impression that Jean-Claude didn't know what to do or where to go. He was lost, in a way, trying to grasp something

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts