Question: CASE STUDY: The Ford Pinto Consumers tolerate a certain amount of outsourcing of jobs as a trade-off for cheaper clothes, electronics, and other desirable objects,

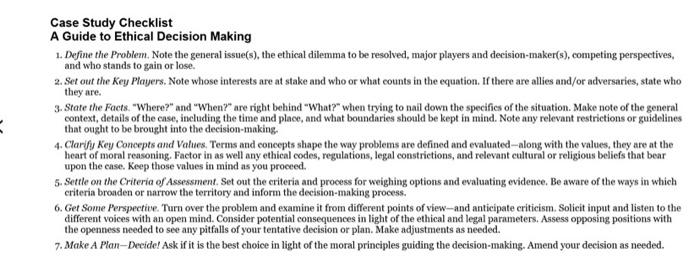

CASE STUDY: The Ford Pinto Consumers tolerate a certain amount of outsourcing of jobs as a trade-off for cheaper clothes, electronics, and other desirable objects, Companies that pay higher wages or use better-quality parts usually have to charge more. This is not always well-received among the buying public. Of course, many consumers don't balk at expensive cups of coffee or higher-priced phones and computers with nice retina screens. However true that is, the majority tolerate outsourcing if it reduces their own living costs. So there we are: Potholes wherever we turn! Nevertheless, the Pinto case is another classic of Business Ethics, It merits a careful study. "Learn from the mistakes of those who came before us" should guide us as we make our own way through life, and be something businesses should take to heart. It's 1971 and the Vietnam War is dragging on. The automotive industry is about to turn over a new leaf. European subcompacts are selling like hotcakes. This is just the catalyst for Ford Motor Company to move into high gear to create a worthy competitor. 'They had a big hit with their first pony-the Mustang, a classic car if there ever was. So you'd think the next one would be just as successful, given the ready audience. Thus, the Ford Pinto. It should be one of those strokes of genius, but it falls short. Right from the get-go, the car has problems. But sales are good and initially the problems seem minor. However, two things doom the enterprise: First, it's a rush job. Secondly, a few engineering shortcuts are taken. Both entail risks. The biggest risk-their worst nightmare-is the location of the fuel tank. Contrary to the practice of the European carmakers (who place the fuel tank over the rear axle), Ford put it behind the rear axle (Jennings, 1993. 218). The way Ford designed it left too little "crush space." In addition, the bumper is significantly lighter (some say "flimsier") than is the norm in other American cars. At no time before or after the Pinto has sach a weak bumper been used on an American car, reports Marianne Moody Jennings. If all this isn't bad enough, the Pinto lacks reinforcing rear sections, making it less crash resistant (Jennings, 218-219). Ford's "Perfect Storm" Basically, Ford created a "perfect storm" with all the problems tied to a vulnerable fuel tank. As a result, the situation escalated. A 1997 report by Mark Dowie of The Atlantic Monthly is telling. The Pinto prototype was crash tested and the car failed the fuel system integrity test in crashes over 20 miles per hour. Such crashes indicated the Pinto was vulnerable to the fuel tank being driven forward, punctured, and fuel leaking in excess of the minimal standard. Such a leak could cause the car to burst into flames. Dowie points out that, "Because assembly-line machinery was already tooled when engineers found this defect, top Ford officials decided to manufacture the car anyway-exploding gas tank and all-even though Ford ouned the patent on a much safer gas tank." Amazingly enough, Ford sold the Pinto, knowing of the defect. Ford did a cost analysis. Remedies would cost an estimated $11 per ear. The cost of a few cups of coffee and the car conld be fixed! However, if 11 million cars and 1.5 million light trucks had to be reealled and repaired, we're talking approximately $137 million (Jennings, 222). At this point, the profit motive won out over safety concerns. "Safety doesn't sell," Ford CEO Lee lacocea reportedly said (Dowie, 1977). That he may have underestimated the consumer seems worth considering. In a move out of the Theatre of the Absurd, Ford modified its advertising. They sought to avoid visions of exploding gas tanks coming to mind. Burning Pintos bave become such an embarrassment to Ford that its advertising agency, J. Walter Thompson, dropped a line from the end of a radio spot that read "Pinto leaves you with that warm feeling" (Dowie, 1977). The Weighting Game: Deaths vs. Repairs In a maeabre turn of events, Ford computed the cost for 180 burn deaths, 180 serious burn injuries, and 2,100 burned vehieles. The unit cost estimate was $200,000 per death, $67,000 per injury, and $700 per vehicle- a bargain at $49.15 million (Jennings, p. 222 ). That's a saving of $87.85 million. Quite a tidy sum! For seven years Ford sold the car, knowing its defects. Yes, seven years. Here's when the wave of self-interest washed over Ford and they lost sight of their duty to protect their customers from injury or death. The road taken by the Ethical Egoist may look like the Yellow Brick Road when you start skipping, but turns into quicksand the farther you go. And it certainly did not end well for Ford. It took years to rebuild their reputation. Nor did it end well for their customers, given that many died, others were injured, and millions of others became disillusioned about buying another Ford automobile. Lawsuits followed. Robert Sherefkin (2003) reports that, "A 1979 landmark case, Indiana vs. Ford Motor Co., made the automaker the first US corporation to be indicted and prosecuted (though found "not guilty") on eriminal homicide charges," Given the knowing disregard for human life, it's not surprising that Ford faced such serious charges. No doubt it was an important, however, painful, lesson for Ford Motor Company to learn. But, if nothing else, Ford is not alone: Many businesses cut corners and compromise standards from time to time, at least to some degree. Looking back what can we see? The problems with the Pinto tarnished Ford's reputation. It takes time to recover from moral failures, as was the case here. And it takes time to rebuild trust. This is as true for corporations as for individuals. Betrayal cuts deep. Whatever savings made in the short term. the long-term cost of paying off deaths rather than repairing the car was both tragic and avoidable. Case Study Checklist A Guide to Ethical Decision Making 1. Define the Problem. Note the general issue(s), the ethical dilemma to be resolved, major players and decision-maker(s), competing perspectives, and who stands to gain or lose. 2. Set out the Key Ployers. Note whose interests are at stake and who or what counts in the equation. If there are allies and/or adversaries, state who they are. 3. State the Facts. "Where?" and "When?" are right behind "What?" when trying to nail down the specifies of the situation. Make note of the general context, details of the case, including the time and place, and what boundaries should be kept in mind. Note any relevant restrictions or guidelines that ought to be brought into the decision-making. 4. Clarfiy Key Concepts and Volues. Terms and concepts shape the way problems are defined and evaluated-along with the values, they are at the heart of moral reasoning. Factor in as well any ethical codes, regulations, legal constrictions, and relevant cultural or religious beliefs that bear upon the ease. Keep those values in mind as you proceed. 5. Settle on the Criteria of Assessment. Set out the eriteria and process for weighing options and evaluating evidence. Be aware of the ways in which criteria broaden or narrow the territory and inform the decision-making process. 6. Get Some Persjective. Turn over the problem and examine it from different points of view-and anticipate criticism. Solicit input and listen to the different voices with an open mind. Consider potential consequences in light of the ethical and legal parameters. Assess opposing positions with the openness needed to see any pitfalls of your tentative decision or plan. Make adjustments as needed. 7. Make A Plan-Decidet Ask if it is the best choice in light of the moral principles guiding the decision-making. Amend your decision as needed