Question: customers, suppliers, and communities in as serious takes place in the firm's business model thow to a way as they track its financial performance. make

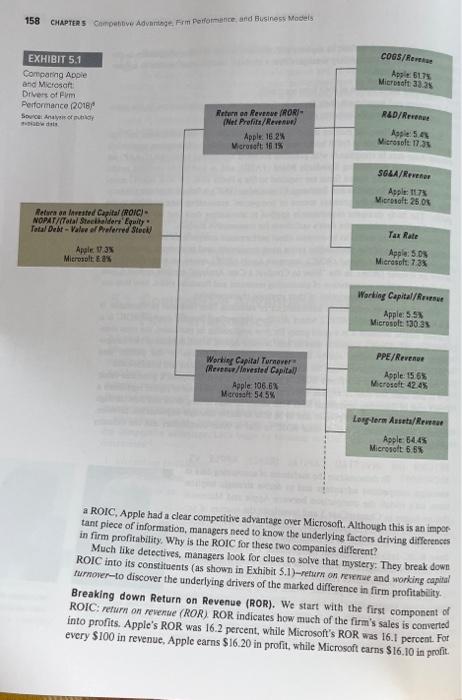

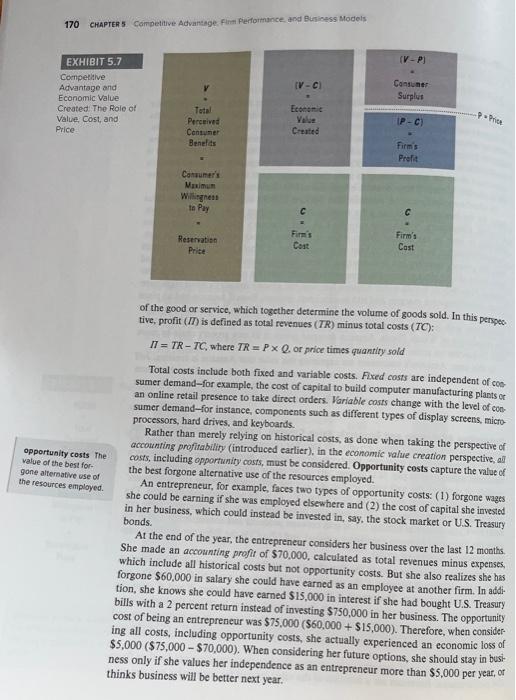

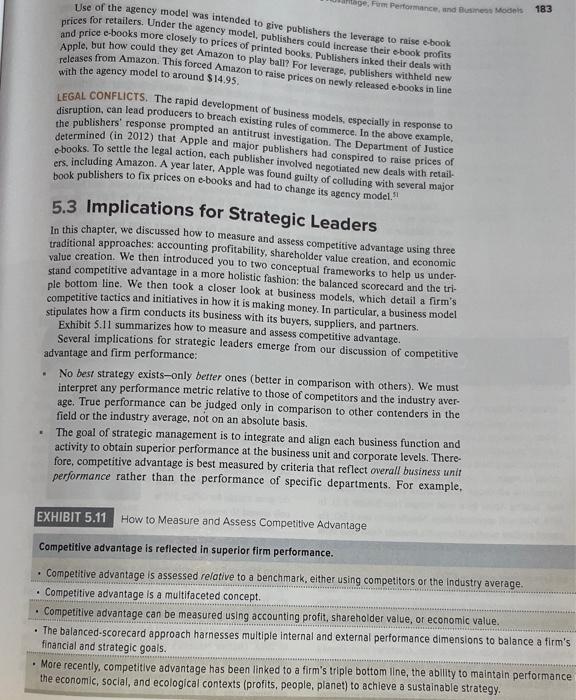

customers, suppliers, and communities in as serious takes place in the firm's business model thow to a way as they track its financial performance. make money). - The triple-bottom-line framework is related to understanding - A business model detaills how the firm conducts stakeholder theory, an approach to understanding its business with its buyers, suppliers, and a firm as embedded in a network of internal and partners. tions and expect consideration in return. The translation of a firm's strategy (where and how managers through the process of formulating and to compete for competitive advantage) into action DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. How do perspectives on competitive advantage dif-_ some of the disadvantages of using shareholder fer when comparing brick-and-mortar stores to on- value as the sole point of view for defining line businesses (e.g. Best Buy versus Amazon, Old implementing a business model. Navy versus Threadless [noted in Strategy High- 3. The chapter discusses seven different business models with a brief description of each. Given light 5.2]). Make recommendations to a primarily the changing nature of many industries, choose describe how the business model of a firm in that industry has changed over the last decade. (If 2. For many people, the shareholder perspective is you prefer, you can describe how a firm's current perhaps the most familiar measure of competitive business model should be changing in the next advantage for publicly traded firms. What are few years ahead.) The Quest for Competitive (A) GAINING AND SUSTAINING competitive advantage is the defining goal of strategio management. Competitive advantage leads to superior firm performenfice, To explain differences in firm performance and to derive strategic implicatiofes. including new strategic initiatives-we must understand how to measure and assess coses petitive advantage. We devote this chapter to studying how to measure and assess cosester forme performance. In particular, we introduce three frameworks to capture the musesiffition nature of competitive adv - Accounting profitability. - Shareholder value creation. - Economic value creation. We then will introduce two integrative frameworks, combining quantitative data with qualitative assessments: - The balanced scorecard. - The triple bottom line. Next, we take a closer look at business models to understand more decply how firms put their strategy into action to make money. We conclude the chapter with practical Implifo. tions for Sirategic Leaders. 5.1 Competitive Advantage and Firm Performance It is easy to compare two firms and identify the better performer as the one with compelitive advantage. But such a simple comparison has its limitations. How does it help us to under. stand how and why a firm has competitive advantage? How can that advantage be measures? And how can we understand it in the context of an entire industry and the everechanging external environment? What strategic implications for managerial actions can we derive from our assessments? These questions may seem simple, but their answers are not. Strategis management researchers have debated them intensely for the past few decades. 2 To address these key questions, we will develop a multidimensional perspective for assess ing competitive advantage. Let's begin by focusing on the three standard performance dimensions.? 1. Accounting profitability 2. Shareholder value 3. Economic value These three performance dimensions generally correlate, particularly over time. Accoant. ing profitability and economic value creation tend to be reflected in the firm's stock price, which in part determines the stock's market valuation. ACCOUNTING PROFITABILITY As we discussed in Chapter 1 , strategy is a set of goal-directed actions a firm takes to giin and sustain competitive advantage. Using accounting data to assess competitive advantage and firm performance is standard managerial practice. When assessing competitive adiantage by measuring accounting profitability, we use financial data and ratios derived from publicly available accounting data such as income statements and balance sheets. 4 Since campetitive advantage is defined as superior performance relarive to other competitors in the same industry or to the industry average, a firm's strategic leaders must be able to accomiplish two critical tasks: 1. Assess the performance of their firm accurately. 2. Compare and benchmark their firm's performance to other competitors in the same industry or against the industry average. Standardized financial metrics found in publicly available income statements and balance sheets allow a firm to fulfill both these tasks. By law, public companies are required to release these data in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FA.SB), and as audited by certified public accountants. Publicly traded firms are required to file a Form 10K (or 10K report) annually with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), a federal regulatory agency. The 10K reporis are the primary source of companies' accounting data available to the public. The lairly stringent requirements applied to accounting data that are audited and Accounting data enable us to conduct direct performance comparisons be andis. Accounting data enable us to conduct direct performance comparisons between different companies. Some of the profitability ratios most commonly used in strategic management are return on imested caplial ( ROIC), return on equity (ROE), retum on assets (ROA), and will find a complete presentation of accounting measures and financial ratios, how they are will find a comple and a brief description of their strategic characteristics: One of the most commonly used metrics in assessing frmester. Ontern on invested capltal (ROIC), where ROIC = Net profits / Invested copitat, 3. retarn on invesied capital (ROIC), where ROIC=N Net profits / Invested capital, 3 ROIC is a. popular metric because it is a good proxy for firm profitability. In particular, the ratio measures how effectively a company uses its total imvested capital, which consists of two components: (1) shareholders equity through the selling of shares to the public, and (2) interest-bearing debr through borrowing from financial institutions and bondholders. As a rule of thumb, if a firm's ROIC is greater than its cost of capital, it generates value; if it is less than the cost of capital, the firm destroys value. The cost of capiral represents a firm's cost of financing operations from both equity through issuing stock and debt through issuing bonds. To be more precise and to be able to derive strategic implications, however, strategic leaders must compare their ROIC to that of other competitors and the industry average. RETURN ON INVESTED CAPITAL (ROIC): APPLE VS. MICROSOFT. To demonstrate the usefulness of accounting data in assessing competitive advantage and to derive strategic implications, let's revisit the comparison between Apple and Microsoft that we began in ChapterCase 5 and investigate the sources of performance differences in more detail. 6 Exhibit 5.1 shows the ROIC for Apple and Microsoft as of fiscal year 2018.. It further breaks down ROIC into its constituent components. This provides important clues for managers on which areas to focus when attempting to improve firm performance relative to their competitors. Apple's ROIC is 17.3 percent, which is 8.5 percentage points higher than Microsoft's ( 8.8 percent). This means that for every $1.00 invested in Apple, the company returned $1.17, while for every $1.00 invested in Microsoft, the company returned $1.09. Since Apple was almost twice as efficient as Microsoft at generating a ROIC, Apple had a clear competitive adyantage over Microsoft. Although this is an important piece of information, managers need to know the underlying factors driving differebces in firm profitability. Why is the ROIC for these two companies different? Much like detectives, managers look for clues to solve that mystery: They break down ROIC into its constituents (as shown in Exhibit 5.1) -refurn on revenue and warking eagital furnover-to discover the underlying drivers of the marked difference in firm profitability. Breaking down Return on Revenue (ROR). We start with the first componcnt of ROIC: neturn on revente (ROR) ROR indicates how much of the firm's sales is comverted into profits. Apple's ROR was 16.2 percent, while Microsoft's ROR was 16.1 percent. Fot every $100 in revenue, Apple earns $16.20 in profit, while Microsoft earns $16.10 in profit. On this metric, Apple and Microsoft do not differ thuch. Ketp in mind, however, that Appic's 2018 revenues were $262 billion, while Microsoft's were $11 billion. Thus, Appie is mare than 2.2 times larger than Microsoft in terms of annwal sales. As we investigate the differences in ROIC further, we will diseover that Microsott has a higher eost strueture than Apple, lind that Appie is able to charge a mueh higher markia for its produets and services than Microsoft: To deive deeper into the drivers of this difference, we need to break down ROR into three idditional financial ratios: - Cost of goods sold (COGS) / Revenue. - Research a development (R\&D)/Revenue. - Selling, general, \& administrative (SGdA)/Revenue. COGS/Revenue. The first of these three ratios, COGS/Revenue, indicates how efficiently a company can produce a good, On this metric, Microsoft turns out to be moch more efficient than Apple, with a difference of 28.4 percentage points (sce Exhibit 5.1 ). This is hecuuse Micrusoft's vast majority of revenues comes from software and online cloud services, with little cost attached to such digitally delivered prodocts and services. In contrast, Apple's revenues were mosely from mobile devices, combining both hardware and software. In particular, the iPhone made up approximately 60 perceat (or over $157 billion) of Apple's total revenues in 2018. R\&D / Revenue Even though Apple is more than two times as large as Microsoft in terms of revenues, it spends much less on research and development or on marketing and sales. Both of these help drive down Apple's cost structure, In particular, the nest ratio, R\& D/Rewnic, indicates how much of each dollar that the firm earns in sales is invested to conduct research and development. A higher percentage is generally an indicator of a stonger focas on innovatioa to improve current products and services, and to come up with new ones. Interestingly, Apple is much less R\&D intensive than Microsoft. Apple spent 5.4 percent on RkD for every dollar of revenue, while Microsoft spent more than three times us much (17.3 percent R\&D). Even considering the fact that Microsoft's revenues were $118 billion versus Apple's $262 billion, Microsoft spent much more on RdD in absolute dollars than Apple (Microsoft: $20 billion: Apple: $14 billion). For every $100 earned in revenues Mierosoft spent $17.30 on RidD, while Apple only spent $5.40. For more than a decade now, Microsoft generally spends the most on R\&D in absolute terms among all technology firms. In contrast, Apple has spent much less on RdD than have other firms in the high-tech industry, in both absolute and relative terms. Apple's co-founder and longtime CEO, the late Steve Jobs, defined Apple's R\&D philosophy as follows: "Innovation has nothing to do with how many R.\&D dollars you have. When Apple came up with the Mac, IBM was spending at lenst 100 times more on RdD. It's not about money. It's about the people you have, how you're led, and how much you get it, n9 SG\&A / Revense. The third ratio in breaking down ROR, SGdA/Revenue, indicates how much of each dollar that the firm earns in sales is invested in sales, general, and administrative (SG\&A) expenses, Generally, this ratio is an indicator of the firm's focus on marketing and sales to promote its products and services. For every $100 earned in revenues Microsoft spent $26.00 on sales and marketing, while Apple spent \$11.70. Even though Microsoft SG\&A intensity was more than twice as high as Apple, given the significant gap in revenues (Microsoft: $118 billion: Apple: $262 billion), each company spent almost $31 billion in marketing and sales, much more than either company spent on R\&D. Microsoft is spending a significant amount to rebuild its brand, especially on CEO Satya Nadella's strategic initiative of "mobile first, cloud first."10 This focus on cloud computiag on mobile devices marks a significant departure from the Windows-centric strategy for PC. of Nadella's predecessor. Steve Ballmer. Yet, by 2017, the Windows and Office combination still generated about 40 percent of Microsoft's total revenues and 75 percent of its profits, Microsoft is working hard to transition the Office business from the oid business model of standalone software licenses ( $150 for Office Home \& Student) to repeat business viu We also note, for completeness, that Apple's effective tax rate in 2018 was 5.0 percent We also note, for completeness, that Apple's effective tax rate in 2018 was 5.0 percetit (with at net income of $59. income of $33.5 billion). Breaking Down Working Capital Turnover. The second component of ROIC is Working Capital Turnover (see Exhibit 5.1). which is a measure of how effectively capital is being used to generate revenue. In more general terms, working capital entails the amount of money a company can deploy in the short term, calculated as current assets minus current liabilities. This is where Apple outperforms Microsoft by a fairly wide margin (106.6 percemt vs. 54.5 percent, respectively). For every dollar that Apple puts to work, it realizes $106.60 of sales, whereas Microsoft realizes $54.50 of sales-so a difference of $52.10. This implies that Apple is almost twice as efficient ( 96 percent) as Microsoft in turning invested capital into revenues. This significant difference provides an important clue for Microsoft's strategic leaders to dig deeper to find the underlying drivers in working capital turnover. This enables executives to uncover which levers to pull to improve firm financial performance. In a next step, therefore, managers break down working capital turnover into other constituent financial ratios, including Working Capital / Revenue; Plant, Property, and Equipment (PPE) / Revenul; and Long-term Assets / Revenue. Each of these metrics is a measure of how effective a particular item on the balance sheet is contributing to revenue. Working Capital / Revenue. The working capital to revenue ratio indicates how much of its working capital the firm has tied up in its operations. Apple (with a working capital to resenue ratio of 5.5 percent) operates much more efficiently than Microsoft (working capital to revenue ratio of 130.3 percent), because it has much less capital tied up in its operations. One reason is that Apple outsources its manufacturing. The vast majority of Apple's mant facturing of its products is done in China by low-cost producer Foxconn, which employs about 1 million people. Moreover, Apple benefits from an effective management of its global supply chain. Although Apple's installed base of iPhone users globally is about 1 billion, one signiffcant area of future vulnerability for Apple is that about 60 percent of annual revenues are based on sales of a single product-the iPhone, depending on model year. Moreover, China accounts for about 20 percent of Apple's total revenues. But demand in China for the newer high-end iPhones such as the iPhone XS Max has been dropping sharply in the face of loca competition from Huawei, Xiaomi, and others. Apple's continued dependence on iPhone sales as well as declining sales in China are pressing issues that Apple CEO Tim Cook neods to address in order to sustain Apple's competitive advantage. PPE / Revenue. The PPE over revenue ratio indicates how much of a firm's revenues are dedicated to cover plant, property, and equipment, which are critical assets to a firm's operations but cannot be liquidated easily. One reason Microsoft's PPE to revemue ratio (42.4 percent) is significantly higher than that of Apple's ( 15.6 percent) is the fact that Microsoft invests huge amounts of money on its cloud business, Azure. To do so, it needs to build hundreds of data centers (large groups of networked competer servers used for the remote storage, processing, or distribution of large amounts of data) across the globe, a costly proposition reflected in high PPE expenditures on a much lower revenue base than Apple. On the upside, Azure is already reporting some $23 billion in sales (in 2018), second only to Amazon's AWS with $27 billion in sales as the world's largest cloud-computing services provider. A second area of future growth for Microsoft is likely to be artificial intelligence (A1). For example, algorithms combing through vast amounts of data on professionals and their networks might be able to tell sales staff on which leads to spend most of their time. This explains why Microsoft paid $26 billion in 2016 to acquire Linkedin, a professional social network with some 250 million monthly active users. Long-term Assets / Revenue. Finally, the Long-term assets/Revente ratio indicates how much of each dollar a firm earns in revenues is tied up in longterm assets. Such assets include anything that cannot be turned into cash or consumed within one year. In the hightech industry, long-term assets include not only plant, property, and equipment but also intangible assets. Intangible assets do not have physical attributes (see discussion of intangible resources in Chapter 4), and include a firm's intellectual property (such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks), goodwill, and brand value. One way to think about this is that intangibles are the missing piece to be added to a firm's physical resource base (that is plant, property, and equipment and current assets) to make up a company's total (long-term) asset base. With a higher Longterm assets/ Renentie ratio. Apple ( 64.4 percent) has much more value tied up in longterm assets than Microsoft (6.6 percent). Because the companies no longer break out their longterm assets into intangible and tangible assets, this figure is a bit harder to interpret. Apple's new campus in Cupertino, California, cost more than $5 billion, making it the most expensive office space ever built. 12 This large investment into longterm assets is one contributing factor why this particular ratio is much higher for Apple than Microsoft. A decper understanding of the fundamental drivers for differences in firm profitability allows leaders to develop strategic approaches. For example, CEO Satya Nadella could rework Microsoft's cost structure, in particular, its fairly high R\&D and SG\&A spending. Perhaps, R\&D dollars could be spent more effectively. Apple generates a much higher return on its R\&D spending. Microsoft's sales and marketing expenses also seem to be quite high, but may be needed to rebuild Microsoft's brand image with a new focus on mobile and cloud computing. LIMITATIONS OF ACCOUNTING DATA. Although accounting data tend to be readily available and we can easily transform them into financial ratios to assess and evaluate competitive performance, they also exhibit some important limitations: - Accosnting data are historical and thus bachvardfooking. Accounting profitability ratios show us only the outcomes from past decisions, and the past is no guarantee of future performance. There is also a significant time delay before accounting data become publicly available. Some strategists liken making decisions using accounting data to driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror. 13 While financial strength certainly helps, past performance is no guarantee that a company is prepared for market disruption. - Accounting data do not consider off-balance sheet items. Off-balance sheet items, such as pension obligations (quite large in some U.S. companies) or operating leases in the retail industry, can be significant factors. For example, one retailer may own al its stores, which would properly be included in the firm's assets, a second retailer may lease all its stores, which would not be listed as assets. All else being equal, the secono 170 CHAPTER 5 Compelitive Advartage. Fint Ferforthance and Busionss Models EXHIBIT 5.7 Compelitive Advantage and Economic value Created The Role Value, Cost, and Price of the good or service, which togcther determine the volume of goods sold. In this penpes tive, profit (I) is defined as total revenues (TR) minus total costs (TC) : =TRTC, where TR=PQ, or price times quantity sold Total costs tnclude both fixed and variable costs. Fixed costs are independent of coo: sumer demand-for example, the cost of capital to build computer manufacturing plants or an online retail presence to take direct orders. Variable costs change with the level of consumer demand-for instance, components such as different types of display screens, microprocessors, hard drives, and keyboards. Rather than merely relying on historical costs, as done when taking the perspective of accounting profitability (introduced earlier), in the economic value creation perspective, all costs, including opportunity costs, must be considered. Opportunity costs capture the value of the best forgone alternative use of the resources employed. in her b bonds. She made an accotanting profit of $70,000, calculated as total revenues minus expenses, which include all historical costs but not opportunity costs. But she also realizes she has forgone $60,000 in salary she could have earned as an employee at another firm. In addition, she knows she could have carned $15,000 in interest if she had bought U.S. Treasury bills with a 2 percent return instead of investing $750,000 in her business. The opportunity cost of being an entrepreneur was $75,000($60,000+$15,000). Therefore, when considering all costs, including opportunity costs, she actually experienced an economic loss of $5,000($75,000$70,000). When considering her future options, she should stay in busit ness only if she values her independence as an entrepreneur more than $5,000 per year, of thinks business will be better next year. LIMITATIONS OF ECONOMIC VALUE CPEATION, A with any tool to assess conpetitive advantage, the cconomic value creation framework also has some limitatiots: - Determining the value of a good in che ejes of convamen is not a simple tark One way to tackle this problem is to look at consumers' purchasing habits for their revealed preferences, which indicate how much each consumer is willing to pay for a prodoct or ser-. vice. In the earlier example, the value (V) the consumer placed on the laptop-the highest price she was witling to pay, or her reservation price-was $1,200. If the firm is able to charge the reservation price (P=$1,200), it eaptures all the ccotomic value croated (VC=$800) as producer surplus or profit (PC=$800). - The value of a good in the eyes of cansumers changes based on income, preferencex time, and other factors. If your income is high, you are likely to place a higher value on some goods (e.g., business-class air travel) and a lower value on other goods (o.g., Greyhound bus travel). In regard to preferences, you may place a higher value on a ticket for a Lady Gaga concert than on one for the New York Philharmonic (or vice versa). As an examrple of time value, you place a higher value on an airline ticket that will get you to an important business meeting tomorrow than on one for a planned trip to take place eight weeks from now. - To measunt firm-level competitive advantage, we magt esfimate the economic value created for all products and services effered by the firm. This estimation may be a relatively easy task if the firm offers only a few products or services. However, it becomes much more complicated for diversified firms such as General Electric or the Tata Group that may offer hundreds or even thousands of different products and services across many indus. tries and geographies. Although the performance of individual strategic business anits (SBUs) can be assessed along the dimensions deseribed here, it becomes mote defficult to make this assessment at the corporate level (more on this in our discussion of diversification strategy in Chapter 8). The economic value creation perspective gives us one useful way to assess competitive advantage. This approach is conceptually quite powerful, and it lies at the center of many strategic management frameworks such as the generic business strategies (which we discuss in the next chapter). However, it falls somewhat short when managers are called upon to operationalize competitive advantage. When the need for "hard numbers" arises, managers and analysts frequently rely on firm financials such as accounting profitability or shareholder walue crearion to measure firm performance. We've now completed our consideration of the three standard dimensions for measuring competitive advantage-accounting profitability, shareholder value, and economic value. Although each provides unique insights for assessing competitive advantage, one drawback is that they are more or less one-dimensional metrics. Focusing on just one performance metric when assessing competitive advantage, however, can lead to significant problems, because each metric has its shortcomings, as listed earlier. We now turn to two more conceptual and qualitative frameworks-the balanced scorecard and the triple bottom line-that attempt to provide a more holistic perspective on firm performance. THE BALANCED SCORECARD Just as airplane pilots rely on a number of instruments to provide constant information about key variables-such as altitude, airspeed, fuel, position of other aircraft in the vicinity, and destination-to ensure a safe flight, so should strategic leaders rely on multiple yardsticks to more accurately assess company performance in an integrative way. The balanced scorecard is a framework to help managers achieve their strategic objectives more effectively, 21 Euhioit 5.6 depicts the balanseg tolich to assess surategic objectives by answeth folter key questions. Br Brainstorning aturten to Eive managers a quick but aso cothes Vicw of the firm quiestions art 1. Hor do cusfomer vient ass? The costiot. cr's perspective corcetaing the comp. ny's products and scrtices links dittery to its revenues and profits. Costazth decide their reservation price fot a pios uct of service based on how thoy kiev t. If the customer views the company's offering favorably, she is wifing to pay anofe for 2 , cnhancing its competitive advantago (assuming production costs are aca below the as. ing price). Managers track customer perception to toeatify ateas to imptove, wett o focus on speed, quataty, service, and cost. In the air-expteis indutry. Gor eratnple, aus. agers learned from thcir customers that many don't really nced neth-day ealivef fir second-day delivery by UPS and FedEx, combined with sophisticated reabtire trickety tools onlinc. 2. How do we create rahue? Answering this question challicnges managers to deviciop stras. gic objectives that cnsure future competitivencss, innovation, and organizational lcass ing. The answer focuses on tho business processes and structures that allow a firf to create cconomic value. One useful inctric is the percentage of revenses obralifed free new product introductions. For cxample, 3M recuires that 30 percent of revenues tert come from products introduced within the past tour years, it A second metric, aimod a atsessing a firm's cxternal learning and collaboration capability, is to stipulate that 1 certain percentage of new products must ortginate from outside the firm's boundarist 2 Through its Connect + Develop program. the consumer prodaets company Procrer 4 Gamble has raised the percentage of new products that originated (at least partly) frter Outsdde PdG to 35 percent, up from 15 percent 31 3. What core competencies do we need? This question focuses managers internally to idettify the core competencies needed to achieve thcir objectives and the accompanyin business processes that support, hone, and leverage those competencies. Honda's cor competency is to design and manufacture small but powerful and highly reliable enciots Its business model is to find places to put its engines, Beginning with motorcycies it 1948, Honda nurtured this core competency over many decades and is leveraging it to reach stretch goals in the design, development, and manufacture of small airplanes. Today, consumers still value reliable, gas-powered engines made by Honda. If 000 sumers start to value electric motors more because of zero emissions, lower mainterurct costs, and higher performance metrics, among other possible reasons, the value of Honda's engine competency will decrease. If this happens, then Tesla's core competency In designing and building high-powered battery packs and electric drivetrains will become more valuable. In turn, Tesla (featured in ChapterCase 1) might then be ahle to leverage this core competency into a strong strategic position in the emerging allelectric car and mobility industry. 4. How do shareholders vew us? The final perspective in the balanced scorecard is the sharcholders' view of financial performance (as diseussed in the prior section). Some of the measures in this area rely on accounting data such as cash flow, operating income, ROIC,ROE, and, of course, total returns to shareholders. Understanding the shareholders' view of value creation leads managers to a more future-oriented evaluation. By relying on both an internal and an external view of the firm, the balanced scorecard combines the strengths provided by the individual approaches to assessing competitive advantage discussed earlier: accounting profitability, shareholder value creation, and economic value creation. ADVANTAGES OF THE BALANCED SCORECARD. The balanced-scorecard approach is popular in managerial practice because it has several advantages. In particular, the balanced scorecard allows strategic leaders to: - Communicate and link the strategic vision to responsible partics within the organimation. - Translate the vision into measurable operational goals. - Design and plan business processes. - Implement feedback and organizational learning to modify and adapt strategic goals when indicated. The balanced scorecard can accommodate both short- and long-term performance metries. It provides a concise report that tracks chosen metrics and measures and compares them to target values. This approach allows strategic leaders to assess past performance, identify areas for improvement, and position the company for future growth. Including a broader perspective than financials allows managers and executives a more balanced view of organizational performance-hence its name. In a sense, the balanced scorecard is a broad diagnostic tool. It complements the common financial metrics with operational measures on customer satisfaction, internal processes, and the company's innovation and improvemeat activities. As an example of how to implement the balanced-scorecard approach, Iet's look at FMC Corp., a chemical manufacturer employing some 5,000 people in different SBUs and earning over $3 billion in annual revenues. 32 To achieve its vision of becoming "the customer's most valued supplier," FMC's strategic leaders initially had focused solely on financial metrics such as return on invested capital (ROIC) as performance measures. FMC is a multibusiness corporation with several standalone profit-and-loss strategic business units; its overall performance was the result of both over-and underperforming units. FMC's managers had tried several approaches to enhance performance, but they turned out to be ineffective. Perhaps even more significant, short-term thinking by general managers was a major obstacle in the attempt to implement an effective business strategy. Searching for improved performance, FMC's CEO decided to adopt a balanced-scorecard approach. It enabled the managers to view FMC's challenges and shortcomings from a holistic, company perspective, which was especially helpful to the general managers of different business units. In particular, the balanced scorecard allowed general managers to focus on-market position, customer service, and product introductions that could generate long-term value. Using the framework depicted in Exhibit 5.7, strategic leaders had to answer tough followup questions sach as: How do we become the customer's thort whect more cxternally focused? What are my division's core com the company goals? What are my division's weaknesses? basis. Implementing a balanced-scorecard approach is not a onctime effort, but tequf continuous tracking of metries and updating of strategic objectives, if needed. If is a fors tinuous process, feeding performance back into the strategy process to assess sts efiecto ness (see Chapter 2). DISADVANTAGES OF THE BALANCED SCORECARD. Though widely implemented by many businesses, the balanced scorccard is not without its critics. " It is importint to toy that the balanced scorecard is a tool for strategy implemenfation, not for strategy formid Fion. It is up to a firm's leaders to formulate a strategy that will enhance the chancei if gaining and sustaining a competitive advantage. In addition, the balaticedrourstid approach provides only limited guidance about which metrics to choose. Difierens titis tions eall for different metrics. All of the three approaches to measuring sompetiti advantage-accounting profitability, shareholder value creation, and cconoasie vilit creation-in addition to other quantitativ using a balanced-scorccard approach. When implementing a balasced scorecard, managers need to be arare that a filift achieve competitive advantage is not so much a reflection of a poor framenork but of strategic fatlure. The balanced scorccard is only as good as the sikills of the manders wat use it: They first must devise a strategy that cnhances the odds of achieving corpettite advantage. Second, they must accurately transiate the strate y int measure and mangec within the balarced-scorecard approach. Je beterich have been selected, the balanced scorecard tracks chosen metries and Once the metrics have been selected, the balanced scorecard tracis chosen mattics at measures and compares them to target valees. It does not, however. provide THE TRIPLE BOTTOM LINE Today, strategic leaders are frequently asked to maintain and improve not only the firmi economic performance but also its social and ccological performance. When serviag as CF0 of PepsiCo, Indra Nooyi responded by declaring the company's vision to be Peformance will Purpose defined by goals in the social dimension (human sustainability to combat obesity is making its products healthier, and the whole person at work to achicve work/life balancel hed ecological dimension (envirommental stastainability in regard to clean water, energy, recyeiff, and so on), in addition to firm financial performance. Strategy Highlight 5.L. discusts Indu Nocyi's triple bottom line initiative in detail. Being proactive along noneconomic dimensions can make good business sense It anticipation of coming industry requirements for "extended producer responsibilits" which requires the seller of a product to take it back for recycling at the end of its life, be German carmaker BMW was proactive. It not only lined up the leading caserocycius companies but also started to redesign its cars using a modular approach. The moduls parts allow for quick car disassembly and reuse of components in the after-sales madit and stakeholder strategy. Nooy was convinced that com- Although PepsiCo's revenues havo remained more of pantes have a duty to society to "do better by doing bet- less fint over the past few years, investors see significatif competitie advantage, which considers not onfy econamic and 2018, Pepsico under Nooyi outperformed Cota-Cols butalsosocialandenvironmentalperformance.AsCEO,CO.byarelativelywidemargia,Duringthisperiod,Peps.NooyideclaredthatthetrueprofitsofanemterprisearenotCosnormalizedstockappreciationwas66percent,whilh. Nooyi declared that the true profits of an enterprise are not Co's normatized stock appreciation was 66 percent, whili. just "revenues minus costs" but "revenues minus costs mi- Coca-Cola's was 25 percent; thus, PepsiCo outperformist fust "revenues minus costs to soclety. "Problems such as pollution or the in. archrival Coca-Cola by 41 percentage points, With betted creased cost of health care to combat obesity impose costs than expected financial results in her last tive years as on society that companies typically do not bear (externatl. CEO, Nooyl stands vindicated after years of criticism. 05. ties). As Nooyi saw it, the time when corporations can just splte opposition, she stuck by her strategit mantra for pass on their externalities to soclety. is nearing an end. network of internal and external constituencies that each make contributions and expect consideration in return (see the discussion in Chapter 1). \begin{tabular}{l} 5.2 Business Moclels: Putting Strategy \\ into Action \\ Strategy is a set of gonl-directed actions a firm takes to gain and sustain superior perfor Use the why, what who and how of business modeis framework to nut \\ \hline \end{tabular} mance relative to competitors or the industry average. The translation of strategy into action takes place in the firm's business model, which details the firm's competitive tactics and initiatives. Simply put, the firm's business model explains how the firm intends to make its buyers, suppliers, and partners, ts How companies do business can sometimes be as important, if not more so, to gaining and sustaining competitive advantage as what they do. Indeed, a slight majority ( 54 percent) business model Stipulates how the fil conducts its busines. with iss buyers, supp? ers, ard partners in order to make mone tion to be more important than process or product innovation. .6 This is because product and process innovation is often more costly, is higher risk, and takes longer to come up with in the first place and to then implement. Moreover, business model innovation is often an area that is overlooked in a firm's quest for competitive advelion. be unlocked by focusing on business model innovation. Strategy Highlight 5.2 takes a closer look at how the online startup Threadless uses business mode Perhaps most important, a firm's competitive advantage based on product innovation. such as Apple's iPhone, is less likely to be made obsolete if embedded within a business model innovation such as Apple's ecosystem of services that make users less likely to leave Apple for a competing product, even if a competitor's smartphone by itself is a better one. Indeed, Apple has about 1 billion iPhone users embedded within its ecosystem made up of many different products and services including iTunes, iOS, App Store, iCloud, Apple Pay, and so on. Rather than substitutes, business model innovation complements product and service innovation, and with it raises the barriers to imitation. This in turn allows a firm that successfully combines product and business model innovation to extend its competitive advantage, as Apple has done since the introduction of the iPod and iTunes business model in 2001. This radical business innovation allowed Apple to link music producers to consumers, and to benefit from each transaction. Apple extended its locus of innovation from mere product innovation to how it conducts its business. That is, Apple provided a two-sided platform for exchange between producers and consumers to take place (see discussion in Chapter 7 on platform strategy for more details). THE WHY, WHAT, WHO, AND HOW OF BUSINESS MODELS FRAMEWORK To come up with an effective business model, a firm's leaders need to transform their strategy of how to compete into a blueprint of actions and initiatives that support the overarching goals. Next, managers implement this blueprint through structures, processes, culture, and procedures. The framework shown in Exhibit 5.10 guides strategic leaders through the process of formulating and implementing a business model by asking the important questions of the why, what, who, and how. We illuminate these questions by focusing on Microsoft, also featured in ChapterCase 5. Threadless: Leveraging Crowdsourcing to Design Cool T-Shirts Threadless, an online design community and apparel store (www.threadiess.com), was founded in 2000 by two students with $1,000 as start-up capital. Jake Nickell Was then at the illinois Institute of Art and Jacob DeHart at Purdue University. After Nickell had won an online T. shirt design contest, the two entrepreneurs came up with a business model to leverage user-generated content. The idea is to let consumers "work for you" and turn consumers into prosumers, a hybrid between producers and consumers. Members of the Threadless community, which is some 3 million strong, do most of the work, which they consider fun: They sabmit T-shirt designs online, and community members vote on which designs they like best. The designs recelving the most votes are put in production. printed, and soid online. Each Monday. Threadless releases 10 new designs and reprints more T-shirts throughThreadless T-shirts is a bit higher than that of competitors; Threadless T-shirts is a bit higher than that of competitors, a in each design contest, In addition, when scoring each ogy to help produce better products is T-shirt design in a contest, Threadiess users have the oped in the Threadless business model. In option to check "/'d buy it. " These features give the theadless is leveraging the wisdom of the Threadless community a voice in T-shirt design and also the the resulting decisions by many partici-. coax community members into making a purchasing cononline forum are often better than decisions mitment. Threadless does not make any significant invest. ind diverse. At Threadless, the customers play a critical role across arketing, sales forecasting, and distribution. The Thread. Old Navy, and Urban Outhitters with their more formulat ss business model translates real-time market research T-shirt designs, in 2017 , revenues for the privately oneed T.shirts that were approved by its community. More- percent pro in profits." KHIIIT 5,10 Why, What, Who, 1. How of Business deis Framework Soos Monorgement The Microsoft example lets us see how a firm can readjust its business model responding: to business challenges. 1. Why does the business model create value? Microsoft's new "mobile first, cloud first" business model creates value for both customers and stockholders. Customers always have the latest software, can access it anywhere, and can collaborate online with other users. Users no longer need to upgrade software or worry about "backward compatibility." meaning the ability to read old (Word) files with new (Word) software. Microsoft enjoys steady revenue that over time provides greater fees than the earlier "perpetual license" model, significantly reduces the problem of software piracy, and balances the cost of ongoing support with the ongoing flow of revenues. 2. What activities need to be performed to create and deliver the offerings to customers? To pivot to the new "mobile first, cloud first" business model, Microsoft is making huge investments to create and deliver new offerings to its customers. The Redmond, Washington-based company needed to rewrite much of its software to be functional in a cloudhased environment. CEO Satya Nadella also decided to open the Office suite of applications to competing operating systems including Google's Android, Apple's iOS, and Linux, an open-source operating system. In all these activities, Microsoft's Azure, its cloud-computing service, plays a pivotal role in its new business model. 3. Who are the main stakeholders performing the activities? Microsoft continues to focus on both the individual end consumer as well as on more profitable business clients. Microsoft's Azure is particularly attractive to its business customers. For example, Walmart, still the largest retailer globally with some 12,000 stores staffed by over 2 million employees and revenues of some $500 billion, runs its cuttingedge IT logistics on Microsoft's Azure servers, rather than Amazon's AWS service, a major competitor to Walmart. Likewise, The Home Depot, one of the largest retailers in the United States, also uster Microsoft Azure for its computing needs. 4. How are the offerings to the ctisfomers created? Microsoft shifted most of its rescurces, including R\&D and customer support, to its cloud-based offerings to not only make them best in class, but also to provide a superior user experience, To appreciate the value of this change in business model, we should consider fot a moment the problems the change allows Microsoft to address. " Before, with the perpetual license model, Microsoft had revenue spikes on the sale buf zero revenues thereafter to support users and produce necessary updates. Now, Microsof matches revenues to its costs and cven comes out further ahead, in that after two yead or so, Microsoft makes more money off a sofiware subscription than a standalone safit. ware license, - Before, customers had a financial disincentive to keep their software current. Now, ksers always have the latest software, can access it anywhere, and can collaborate online with other users without worries about backward compatibility. - Perhaps most impressively, the new model doals effectively with software pitacy. Before, Microsoft suffered tremendous losses through software piracy. This affecti consumers too, as the cost of piracy is borne by legal consumers to a large dezree Now, pirating cloud-based software is much more difficult because Mictosoft canl eas fly monitor how many users (based on unique internet protocol (IP] addresses) att using the same logein information at different locations and perhaps even at the same time, Once the provider suspects piracy, it tends to disabie the accounts as this wost against the terms of serviee agreed upon when purchasing the software, not to mes tion that copyright infringements are inegal. Indeed. the scope of the piracy problem is driven home by the survey ba confess to pirating software, POPULAR BUSINESS MODELS Given their critical importance to achieving competitive adyantage, business models are constantly evolving. Below we discuss some of the more popular business models: 49 - Razor-razor-blades - Subscription - Pay-as-you-go - Freemium - Wholesale - Agency - Bundling Understanding the more popular business models today will increase the tools in your strategy toolkit. - Razor-razor-blades. The initial product is often sold at a loss or given away to drive demand for complementary goods. The company makes its money on the replacement part needed. As you might guess, it was invented by Gillette, which gave away its razors and sold the replacement cartridges for relatively high prices. The razor-razorolads model is found in many business applications today. For example, HP charges little for its laser printers but imposes high prices for its replacement toner cartridges. Likewise, The Home Depot, one of the largest retailers in the United States, atso ever Microsoft Azure for its computing needs. 4. How are the offerings to the custanters creared? Microsoft shifted most of its resoutcty, including R.DD and customer supnort, to its cloud-based offerings to not only thefly them best in class, beit also to provide a superior user experience. To appreciate the value of this change in business model, we should consider he a moment the problems the change allows Microsoft to address. - Before, with the perpetual license model, Microsoft had revenue spikes on the sale bat zero revenues thereafter to support users and produce necestary updates, Now, Mictosof matches reverues to its costs and even comes out further ahead, in that after two jties or so, Microsoft makes more money off a software subscription than a standalone soff. ware license, - Before, customers had a financial disincentive to keep their software current. Now, usen always have the latest software, can access it anywhere, and can collaborate online wits other users without worrics about backward compatibility. - Perhaps most imnressively, the new model deals effectively with software pitacy. Before, Microsoft 5 uffered tremendous losses through software piracy. This affects consumers too, as the cost of piracy is borne by logal consumers to a large degrec. Now, pirating cloud-based software is much more difficult because Microsoff can cty ily monitor how many users (based on unique internet protocol [IP] addresses) art using the same login information at different focations and perhaps even at the kame time. Once the provider suspects piracy, it tends to disable the accounts as this gees tion that copyright infringements are illegal. Indeed, the seope of the piracy problem is driven home by the surveybased claim that some 60 percent of computer unets confess to pirating software, 4 POPULAR BUSINESS MODELS Given their critical importance to achieving competitive advantage, business modeis are constantly evolving. Below we discuss some of the more popular business models.- - Razor-razorblades - Subscription - Pay-as-you-go - Frcemium - Wholesale - Agency - Bundling Understanding the more popular business models today will increase the tools in your strategy toolkit. - Razor-razor-blades. The initial product is often sold at a loss or given away to drive demand for complementary goods. The company makes its money on the replacemedt part needed. As you might guess, it was invented by Gillette, which gave away its razos and sold the replacement cartridges for relatively high prices. The razor-razorblde model is found in many business applications today. For example, HP charges little for its laser printers but imposes high prices for its replacement toner cartridges. Likewise, The Home Depot, one of the largest retailers in the United States, also uster Microsoft Azure for its computing needs. 4. How ane the offerines to she cusfomers created? Microsoft shiffed most of its resolitets, including RED and customer support, to its cloud-based offerings to not only thake, them best in class, but also to provide a superior user experience. To appreciate the value of this change in business model, we should consider for a moment the problems the change allows Microsoft to address. - Before, with the perpetual license model, Mierosont had revenue spikes on the sale by zero revenues thereafter to support users and produce necessary updates, Now, Mictosof matches revenues to its costs and even comes out further ahead, in that after two yeaty or so, Microsoft makes more money off a software subscription than a standakot soft. ware license. - Before, customers had a financial disincentive to keep their software current. Non, Esers always have the latest software, can access it anywhere, and can collaborate online wit. other users without worries about backward compatibility. - Perhaps most impressively, the new model deals effectively with software piracy. Before, Mierosof suffered tremendous losses through software piracy. This affects consumers too, as the cost of piracy is borne by legal consumers to a large degree. Now, pirating cloudbased software is much more difficult because Microsoft can eas. ily monitor how many users (based on unique internet protocol [IP] addresses) art using the same log-in information at different locations and perhaps even at the same time. Once the provider suspects piracy, it tends to disable the accounts as this goes against the terms of service agreed upon when purchasing the software, not to mestis driven home by the surveysbased claim that some 60 percent of computer users confess to pirating software, ,i. POPULAR BUSINESS MODELS Given their critical importance to achieving competitive advantage, business models are constantly evolving. Below we diseuss some of the more popular business models 40 - Razor-razor-blades - Subscription - Pay-as-you-go - Frecmium - Wholesale - Agency - Bundling Understanding the more popular business models today will increase the tools in your strategy toolkit. - Razor-razor-blades. The initial product is often sold at a loss or given away to drive demand for complementary goods. The company makes its money on the replacemant part needed. As you might guess, it was invented by Gillette, which gave away its rators and sold the replacement cartridges for relatively high prices. The razor-razorblade model is found in many business applications today. For example, HP charges listefor its laser printers but imposes high prices for its replacement toner cartridges. - Subscription. The subscription model has been traditionally used for priat magazines and newspapers. Users pay for access to a product or service whether they ate the product or service during the payment term or not. Microvoft uses a subseription-based model for its new Office 365 suite of application software. Other induntries that use this model presently are cable television, cellular service providers, satellite radio, internet service providers, and health clubs. Netflix also uses a subscription model. - Pay-a5-you-go. In the pay-as-you-go business model, users pay for only the services they consume. The pay-as-you-go model is most widely used by utitities providing power and water and cell phone service plans, but it is gaining thomentum in other areas sach as rental cars and cloud computing such as Microsoft's Azare. - Freemium. The freemium (free + premitum) businest model provides the basic features of a product or service free of charge, but charges the user for premium services such as advanced features or add-ons. 50 For cxample, companies may provide a minimally supported version of their software as a trial (e.g., business application of video game) to give users the chance to try the product. Users later have the option of purchasing a supported version of software, which inclades a full set of product features and product support. Also, news providers such as The New York Times and The Wall Street Jourmal use a freemium model. They frequently provide a small number of articles for free per month, but users must pay a fee (often a flat rate) for unlimited access (including a library of past articles). - Ultra-low cost. An ultra low-cost business model is quite similar to freemium: a model in which basic service is provided at a low cost and extra items are sold at a premium. The business pursuing this model has the goal of driving down costs. Examples include Spirit Airlines (in the United States), Ryanair (in Europe), or AirAsia, which provide minimal flight services but allow customers to pay for additional services and upgrades a la carte, often at a premium. - Wholesale. The traditional model in retail is called a wholesale model. The book publishing industry is an example. Under the wholesale model, book publishers would sell books to retailers at a fixed price (usually 50 percent below the recommended retail price). Retailers, however, were free to set their own price on any book and profit from the difference between their selling price and the cost to buy the book from the publisher (or wholesaler). - Agency. In this model the producer relies on an agent or retailer to sell the product, at a predetermined percentage commission. Sometimes the producer will also control the retail price. The agency model was long used in the entertainment industry, where agents place artists or artistic properties and then take their commission. More recently we see this approach at work in a number of online sales venues, as in Apple's pricing of book products or its app sales. (See further discussion following.) - Bundling. The bundling business model sells products or services for which demand is negatively correlated at a discount. Demand for two products is negatively correlated if a user values one product more than another. In the Microsoft Office Suite, a user might value Word more than Excel and vice versa. Instead of selling both products for $120 each, Microsoft bundles them in a suite and sells them combined at a discount, say $150. This bundling strategy allowed Microsoft to become the number-one provider of all major application software packages such as word processing, spreadsheets, slideshow presentation, and so on. Before its bundling strategy, Microsoft faced strong competition in each segment. Indeed, Word Perfect was outselling Word, Lotus 1-2-3 was outselling Excel, and Harvard Graphics was outselling PowerPoint. The problem for Microsoft's competitors was that they did not control the operating system (Windows), which made their programs less seamless on this operating system. In addition, the competitor prod ucts to Microsoft were offered by three independent companies, so they lacked prod option to bundle them at a discount. DYNAMIC NATURE OF BUSINESS MODELS Business models evolve dynamically, and we can see many combinations and permutations Sometimes business models aro tweaked to respond to disruptions in the market, eflorty that can conflict with fair trade practices and may even prompt government interverlion. COMBINATION. Telecommunications companies such as AT\&T or Verizon, to take one industry, combine the razor-razorblade model with the subscription model. They frequenty provide a basic cell phone at no charge, or significantly subsidize a high-end smariphone, when you sign up for a two-year wireless service plan. Telecom providers recoup the subsidy provided for the smartphone by requiring customers to sign up for lengthy service pless. This is why it is so critical for telecom providers to keep their churn rate-the proportion of subseribers that leave, especially before the end of the contractual term-as low as possible. EVOLUTION. The freemium business model can be seen as an evolutionary variation on the razor-razorblade model. The base product is provided free, and the producer finds other ways to monetize the usage. The freemium model is used extensively by open-soarce software companies (e.g., Red Hat), moblle app companies, and other internet businesses. Many of the free versions of applications include advertisements to make up for the cosi of supporting nonpaying users. In addition, the paying premium users subsidize the free users. The frecmium model is often used to build a consumer base when the marginal cost of adding another user is low or even zero (such as in software sales). Many onlize video games, including massive multiplayer online games and app-based mobile games, follow a variation of this model, allowing basic access to the game for free, but charging for poner. ups, customizations, special objects, and similar things that enhance the game experitece for users. DISRUPTION. When introducing the agency model, we mentioned Apple and book pab. lishing, and you are aware of how severely Amazon disrupted the traditional wholesals model for publishers. Amazon took advantage of the pricing flexibility inherent in the wholesale model and offered many books (especially e-books) below the cost that other retailers had to pay to publishers. In particular, Amazon would offer newly released bestseters for $9.99 to promote its Kindle e-reader. Publishers and other retailers strongly objected because Amazon's retail price was lower than the wholesale price paid by retailers competing with Amazon. Moreover, the $9.99 e-book offer by Amazon made it untenable for other retailers to continue to charge $28.95 for newly released hardcover books (for which they had to pay $14 to $15 to the publishers). With its aggressive pricing. Amazon not only devalued the printed book, but also lost money on every book it sold. It did this to increase the iumber of users of its Kindle e-readers and tablets. ESPONSE TO DISRUPTION. The market is dynamic, and in the above example book pubshers looked for another model. Many book publishers worked with Apple on an agency proach, in which the publishers would set the price for Apple and receive 70 percent of e revenue, while Apple received 30 percent. The approach is similar to the Apple App ore pricing model for iOS applications in which developers set a price for applications 1. Apple retains a percentage of the revenue. Use of the agency model was intended to give publishers the leverage to ruise ebook prices for retailers. Under the agency model, publishers could increase their ebook profits and price e-books more closely to prices of printed books. Publishers inked their deals with Apple, but how could they get Amazon to play ball? For leverage, publishers withheld new releases from Amazon. This forced Amazon to r