Question: Question: What is translanguage? Explain why? Prerace IM f you have chosen to read The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning, you are probably

Question: What is translanguage? Explain why?

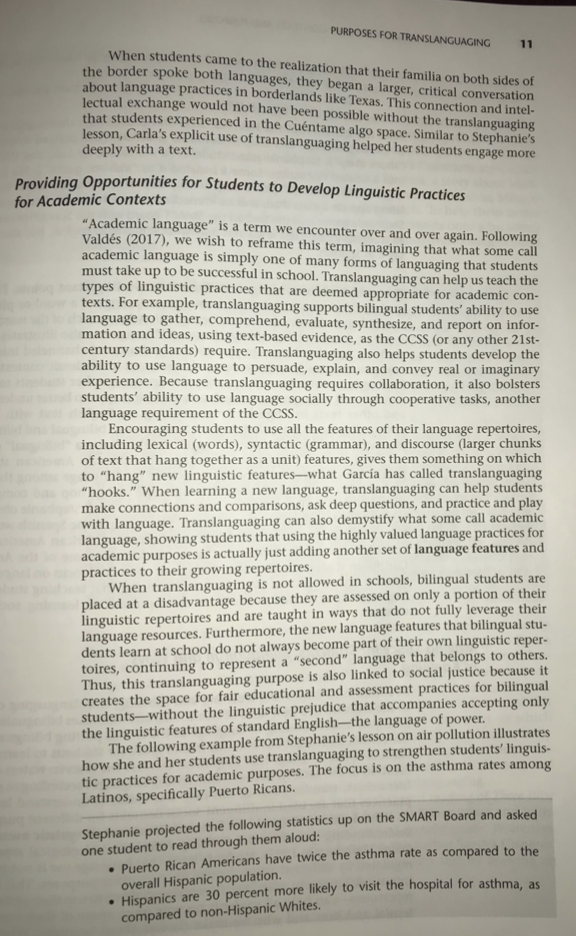

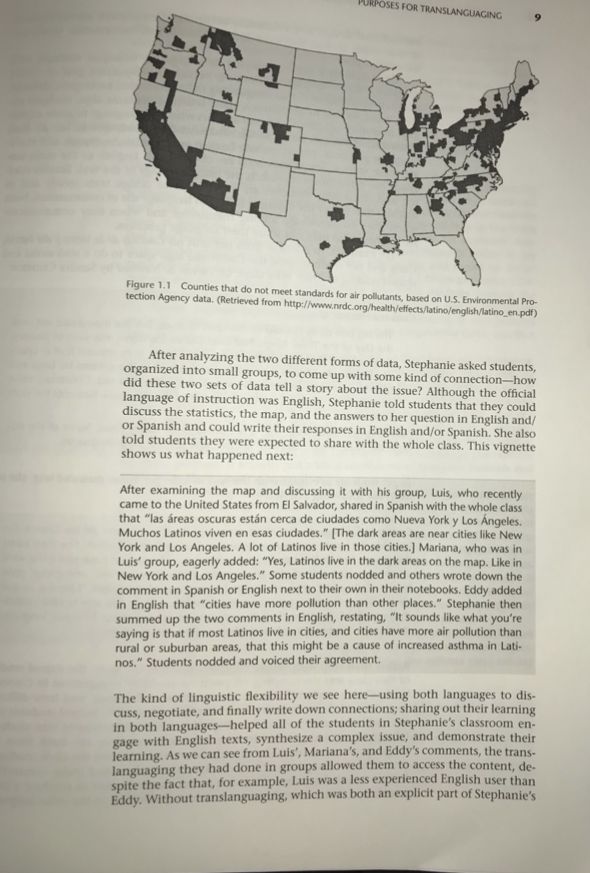

Prerace IM f you have chosen to read The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning, you are probably an educator-a teacher, a curric- ulum developer, a professional development provider, a school administrator, or other school personnel. And like most educators, you probably have stu- dents in your classrooms and schools who speak languages other than English (LOTE) and you are interested in how to further their education, including their English language and literacy development. This book is for you. This book shows teachers, administrators, consultants, and researchers how translanguaging, a way of thinking about and acting on the language practices of bilingual people, may hold the key to successfully educating bilin- gual students. The translanguaging pedagogy that we put forward in this book is purposeful and strategic, and we demonstrate how teachers can use translan- guaging to 1. Support students as they engage with and comprehend complex content and texts 2. Provide opportunities for students to develop linguistic practices for aca- demic contexts 3. Make space for students' bilingualism and ways of knowing 4. Support students' socioemotional development and bilingual identities These four purposes frame the translanguaging pedagogy, and they work to- gether to advance the primary purpose of translanguaging-social justice- ensuring that bilingual students, especially those who come from language minority groups, are instructed and assessed in ways that provide them with equal educational opportunities. Translanguaging classrooms are aligned with the global and local realities of the 21st century. These dynamic classrooms advance the kinds of practices that college and career-readiness standards demand, as they enhance bilingual students' critical thinking and creativity. Teachers learn to expand and localize their teaching in ways that address all content and language standards, and integrate home, school, community, and societal practices and understand- ing. Translanguaging classrooms also allow teachers to carry out the mandates of the growing number of states that are adopting seals of biliteracy to reward students' bilingual abilities. At the time of this writing, 14 states have adopted seals of biliteracy. WHO SHOULD READ THIS BOOK? This book has been written specifically with bilingual students in 4th-12th grades in mind. Teachers and other educational leaders can use this book to guide teaching, instructional programming, and action-oriented research in Our primary audience is teachers. Any teacher, whether monolingual or bilingual, and whether involved in a program officially designated as English- any context. ix MacBook Pro PREFACE professional-a teacher of Engin could be a specialized language teacher or lingual students medium' or bilingual education, can create a translanguaging classroom. Yo as an additional language, bilingual education, home language literacy.ot Won language general education teacher of either children or adolescents, school Teachers and administrators are capable of building instructional spaces that go beyond our traditional understanding about programs for of a specific content area at the secondary level, or even the principal and biliterate (experienced bilinguals), whereas others' bilingualism and bi languages in addition to English. Some of these students are highly bilingual Many, if not most, classrooms are multilingual, with students who speak have developed strong academic foundations through quality school systems, literacy is emerging (emergent bilinguals). Some of these bilingual leatsvets where your students fall within bilingual or educational progressions, this while others may have experienced limited formal schooling. Regardless of Because of the important place of bilingual Latino students in U.S. educa and bilingual instructional settings-to help you understand translanguaging tion, this book emphasizes the context of Latino students-in English-medium classrooms. Because we know that translanguaging is not limited to Spanish- English bilingualism, we also draw on examples from English-medium class rooms that include bilingual students from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds. Whether your students are speakers of Spanish, Mandarin, Ko- rean, Karen, Pular, or any other language, the principles for translanguaging Research and practice on bilingualism at U.S. schools has focused nar. rowly on English language learners' content and language learning, generally book demonstrates innovative ways of educating them. in the classroom are the same. in English-medium classrooms, and reflecting a language-as-problem or det cit orientation. In contrast, The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning takes a much broader approach. We focus on all bij lingual students, including those who are emergent bilinguals, as well as those who are seen by the academic mainstream as English speakers but speak lan- guages other than English at home. We show teachers how to identify and build on the varied bilingual performances of all bilingual students, regardless of whether or not they perform well academically in English or another lan- guage, and regardless of whether they are learning in English-medium, bilin- gual, or LOTE classrooms. We bring the translanguaging pedagogy to life through vignettes from three very different classrooms: A 4th-grade dual-language bilingual education classroom of students who speak English, Spanish, or both at home, taught by a bilingual (Spanish- English) teacher in Albuquerque, New Mexico An 11th-grade English-medium social studies classroom of students who speak English, Spanish, or both at home, taught by a monolingual teacher in New York City they aim for academic achievement and language development in English. Bilingual education "English-medium classes and programs officially use English for instructional purposes, and classes and programs use two or more languages for instructional purposes, and they aim for bl- literacy and academic performance in two languages. subject to language majority students, whereas home language literacy classes teach that language "In the United States, world language refers to a class focused on the teaching of a LOTE as a to bilingual students and hopel English as an acalelong hanglages eachers could teach only the subject (English literacy) or be classroom teachers of all subjects. Bilingual teachers are classroom teachers teaching subjects through two languages. We use Latino not as a "Spanish" word with an "o" inflection, but simply as a word that is inclu- . wacBook Pro PREFACE math 7th-grade English-medium math and science classes that include emer- gent bilinguals who speak Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, French, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Korean, Mandingo, and Pular (Pula) at home, co-taught by a and science teacher and an Es, teacher in Los Angeles, California Taustarichand varied cases clearly demonstrate how teachers can adapt the pedagogy that we in for all , whatever their bilingualism looks like, in whatever instructional context. WHAT ARE THE KEY COMPONENTS OF A TRANSLANGUAGING PEDAGOGY? The central innovative concept in this book for teachers as not on languages, as has been often the proses buto bilingualism that is centered but on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable" (p. 45). This book builds on that approach in three important ways. First, we describe the translanguaging corriente,' the natu- ral flow of students' bilingualism through the classroom. Second, we propose the dynamic translanguaging progressions, which is a flexible model that allows teachers to look holistically at bilingual students' language performances in specific classroom tasks from different perspectives at different times. Third, we introduce a translanguaging pedagogy for instruction and assessment that teachers can use to purposefully and strategically leverage the translan- guaging corriente produced by students. Translanguaging classrooms have two important dimensions. First, teach- ers observe students' languaging performances, and then describe and assess their complex language practices. Then teachers adapt and use the translan- guaging pedagogy for instruction and assessment to leverage the translanguag. ing corriente for learning. Our work revolves around three principles: 1. Bilinguals use their linguistic repertoires as resources for learning, and as identity markers that point to their innovative ways of knowing, being, and communicating. 2. Bilinguals learn language through their interaction with others within their home, social, and cultural environments. 3. Translanguaging is fluid language use that is part of bilinguals' sense- making processes. Spain Tobi Tue Edu 06 Translanguaging Corriente We suggest that the translanguaging corriente, produced and driven by the positive energy of students' bilingualism, flows throughout all classrooms. Metaphorically, we think about the translanguaging corriente as a river cur- rent that you can't always see or feel, but that is always present, always mov- ing, and responsible for changes in the classroom) landscape. Sometimes the translanguaging corriente flows gently under the surface, for example, in classrooms where teachers do not generally tap into students' home language practices for learning. At other times the translanguaging corriente is much stronger, for example, in bilingual classrooms or English-medium classrooms that do draw on students' home language practices. * We use the Spanish word corriente, which is a cognate with the English word current. Through out the book we use other Spanish terms to reflect our own language practices. Because Spanish constitutes the language practices of over three fourths of U.S. bilingual students, this book pays special attention to the Latino population. However, educators working with other language groups might want to use terms in other languages that maintain the spirit of these terms. xl PREFACE To feel the translanguaging corriente, all you have to do is take a step back from your daily routine and listen and look. Listen hard to what your students their intrapersonal voices (the unvoiced dialogues they have in their heads on the playground. If you listen hard enough you might be able to perceive say to you and their peers, Inside the classroom, hallways, and cafeteria, and with themselves or friends). Listen also to the conversations that take place when their families and peers are present; try to hear what is being said and way allows you to hear your students' voices anew, and puts you in touch with the translanguaging corriente, even if it is not obviously at the surface of your how it is said, as well as what is not being said and why. Listening in this communicates and also through the ways that we have chosen to use words In this book the translanguaging corriente runs through the content it in Spanish in this predominately English-language text, without any italics. foreign; they are simply part of our narrative, always present and part of us, We do this to indicate that, for us, the Spanish features we use are not alien or Appendix into Spanish because, as we said earlier, this is the largest population of U.S. bilingual students and in the classrooms featured in this book. How even when we are writing in English. We translate some documents in the ever, you can translate the English text in these documents to any of the lan- guages in your classroom as one means of strengthening the translanguaging corriente in your classroom. classroom. Dynamic Translanguaging Progressions The notion of the translanguaging corriente moves us from the concept of linguistic proficiency, which is assumed to develop along a relatively linear path in more or less the same way for all bilingual learners, to one of linguistic performance. The dynamic translanguaging progressions enable teachers to do the following: Gauge the students' different bilingual performances on different tasks from different perspectives Distinguish between general linguistic performance (bilingual students' ways of performing academic taskse.g., express complex thoughts ef- fectively, explain things, persuade, argue, compare and contrast, recount events , tell jokes--without regard to the language used to express these tasks) and language-specific performance (bilingual students' use of features corresponding to what society considers a specific language or variety) Leverage the translanguaging corriente for learning in their classes . Teachers in translanguaging classrooms use the dynamic translanguaging progressions to document their students' language performances on specific classroom-based tasks--in any language. Translanguaging Stance, Design, and Shifts The translanguaging pedagogy in this book encompasses both instruction and assessment, and is structured into three interrelated strands: the translan- guaging stance, design, and shifts. A stance refers to the philosophical, ideological, or belief system that teachers draw from to develop their pedagogical framework. Teachers with a translanguaging stance believe that bilingual students' many different lan- guage practices work juntos/together, not separately, as if they belonged to PREFACE different realms. Thus, the teacher believes that the classroom space must pro mote collaboration across content; languages; people, and home, school, and community. A translanguaging stance sees the bilingual child's complex lan- guage repertoire as a resource, never as a deficit. Designing translanguaging instruction and assessment involves integrat ing home, school, and community language and cultural practices. The move. ment is created by the interaction between the translanguaging corriente and the teacher and students' joint actions, which enable bilingual students to integrate their home and school practices. Designing translanguaging instruc- tion also means planning carefully (e.g., the grouping of students; elements of planning-essential ideas, questions, and texts; content, language, and translanguaging objectives; culminating projects; design cycle; pedagogical strategies). The translanguaging design is a flexible framework that teachers in English-medium and bilingual classrooms can use to develop curricular units of instruction, lesson plans, and classroom activities. The flexible design is the pedagogical core of the translanguaging classroom, and it allows teachers and students to address all content and language standards and objectives in equitable ways for all students, particularly bilingual students who are often marginalized in mainstream classrooms and schools. Designing assessment to set the course of the translanguaging corriente means including the voices of others, taking into account the difference between content and language, and between general linguistic and language-specific performances, and giv- ing students opportunities to perform tasks with assistance from other people and resources, when needed. Because the translanguaging corriente is always present in classrooms, it is not enough to simply have a stance that recognizes it and a design that leverages it. At times it is also important to follow the dynamic movement of the translanguaging corriente. The translanguaging shifts are the many mo- ment-by-moment decisions that teachers make all the time. They reflect the teacher's flexibility and willingness to change the course of the lesson and assessment, as well as the language use planned for it, to release and support students' voices. The shifts are related to the stance, for it takes a teacher will- ing to keep meaning-making and learning at the center of all instruction and assessment to go with the flow of the translanguaging corriente. USING THIS BOOK We have three purposes for this book. First, we want educators and researchers to see a clearly articulated translanguaging pedagogy in practice. The exam- ples from three very different classrooms stimulate concrete thinking about students, classrooms, programs, schools, practices, and research in different bi/multilingual communities. Second, we want to guide teachers' efforts to adapt the translanguaging pedagogy put forth in this book to any translan- guaging context. Third, we provide the foundation for teachers and research- ers to gather empirical evidence in translanguaging classrooms, which will help refine theory and strengthen practice. We provide templates and examples from our focal bilingual and English- medium classrooms to assist you in designing instructional units, lessons, and assessments that identify and build on the translanguaging corriente in your classroom, school, and community context. When teachers enact a translan- guaging stance, implement a translanguaging design for instruction and assess- ment, and intentionally shift their practices in response to student learning, they help fight the English-only current of much U.S. educational policy and practice and advance social justice. PREFACE languaging We have divided the book into three parts: Part 1: Dynamic Bilingualism at School This part of the book focuses on the "what" and "why" of trans Part II: Translanguaging Pedagogy This part of the book focuses on how to create a translanguaging pedagogy Part III: Reimagining Teaching and Learning through Translanguaging to enhance students' performances in different standards and literacy, This part of the book focuses on how a translanguaging pedagogy works develop their socioemotional identity, and advance social justice, readers will learn and be able to do with chapter material. This is then fol. We divide each chapter into three parts. Learning objectives lay out what lowed by the core of the chapter--vignettes from classroom practices, tools, templates, or frameworks. Each chapter ends with questions and activities that pre-service and practicing teachers can use to reflect on aspects of translan. guaging classrooms, as well as "take action" in their contexts. As a whole, the gogy in specific contexts. They also assist practitioners in developing, imple- taking action questions guide educators to develop a translanguaging peda- micen ting, monitoring, and evaluating their translanguaging pedagogy in pple tice. We encourage you to work through these questions and activities with a close community of educators so that you can support one another as you explore and take up the translanguaging corriente in your classroom. We invite you now to become a reflective practitioner and let yourself be meaning in in- swept up by the translanguaging corriente, as we explore struction and how to teach by capitalizing on its ebbs and flows. We hope that together we will See and hear the translanguaging corriente that already exists in class. rooms and schools Learn how to intentionally, purposefully, and strategically navigate the translanguaging corriente in both instruction and assessment by applying the translanguaging stance, design, and shifts Demonstrate ways that bilingual students and teachers leverage the translanguaging corriente to learn content, develop language, make space for bilingual ways of knowing, and foster more secure socio-emotional identities Become more critical as we take up the stance of reflective practitioner and/or critical researcher and work toward social justice Show the kinds of challenges educators may face in translanguaging class- rooms and reflect on how to overcome them Launch an action-oriented, social justice agenda to strengthen translan- guaging pedagogy, practice, and research in diverse multilingual contexts. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book was the result of much negotiation among ourselves and with our editor, Rebecca Field. Although the process was difficult at times, Rebecca pushed our thinking, our words, and the manuscript itself. What we never told you when things were difficult-gracias, Rebecca. We also want to acknowledge the insights gained from Kathy Escamilla, Jamie Schissel, Guadalupe Valds, and other reviewers. Garca also acknowl- edges a summer 2015 Visiting Appointment at the University of Cologne, and her colleague, Julie Panagiotopoulou, for the space given to her to revise this manuscript. PART I DYNAMIC BILINGUALISM AT SCHOOL CHAPTER 1 Translanguaging Classrooms: Contexts and Purposes LEARNING OBJECTIVES Define translanguaging Explain how translanguaging can be used by teachers in different types of classroom contexts Summarize the four purposes of translanguaging and how they serve the overarching purpose of social justice Give concrete examples to illustrate translanguaging purposes in practice Begin to profile your classroom action. Many of the teachers we have worked with have "aha moments" when they stop and listen to the ways students use language in their class- rooms. For example, two students negotiate in Spanish over a math problem posed to them in English. One student with more experience in English qui- etly explains the directions to a newly arrived student from China. A group of students joke with one another using word play and English/Spanish puns. Once you take up this new lens for observing your bilingual students, you will notice new and exciting things about the way they language, which can guide the ways you plan, teach, assess, and advocate for their needs. Our use of the verb "to language" (e.g., "languaging," "translanguaging") reflects our under- standing of language use as a dynamic communicative practice. A translanguaging classroom is any classroom in which students may de- ploy their full linguistic repertoires, and not just the particular language(s) that are officially used for instructional purposes in that space. These class- rooms can be developed anywhere we find students who are, or are becoming, bilingual. This includes classrooms that only use English as the official lan- guage for instruction (i.e., English-medium classrooms, including English as a second language (ESL) classrooms, whether pull-out, push-in, or structured English immersion programs), as well as bilingual (i.e., dual language, transi- tional) and world language or heritage language classrooms. We refer to the 1 TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CONTEXTS AND PURPOSES students in translanguaging classrooms as bilingual students, by which we mean well as more experienced bilinguals who can use two or more languages with emergent bilinguals who are at the early stages of bilingual development, as relative ease, although their performances vary according to task, modality, and language. Our use of the term emergent bilingual in this book includes sty. dents who are officially designated by schools as "English language learners Spanish, Arabic, Mandarin). We do not use the term ELL because it renders the ("ELLS);" as well as English speakers who are learning other languages languages other than English (LOTE) in the emergent bilinguals' developing linguistic repertoires invisible. We do, however, use this term when it refers to the official school designation. lear (e. be TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS A translanguaging classroom is a space built collaboratively by the teacher and bilingual students as they use their different language practices to teach and learn in deeply creative and critical ways. The term translanguaging comes from the Welsh trawsieithu and was coined by a Welsh educator, Cen Williams (1994, 2002), who developed a bilingual pedagogy in which students were asked to alternate languages for the purposes of receptive or productive use. For example, students might be asked to read in English and write in Welsh and vice versa to deepen and extend their bilingualism. Since Colin Baker translated the Welsh term to English in 2001, translan- guaging has been extended by many scholars to refer to both the complex language practices of bilingual and multilingual individuals and communities, as well as the pedagogical approaches that draw on those practices. Garca (2009) explains that translanguaging is an approach to bilingualism that is centered not on languages as has been often the case, but on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable (p. 45). From a linguistics perspective, Otheguy, Garca, and Reid (2015) define translanguaging as the deployment of a speaker's full linguistic repertoire without regard for watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named languages (p. 281). According to Flores and Schissel (2014, pp. 461-462): Translanguaging can be understood on two different levels. From a sociolinguistic perspective it describes the fluid language practices of bilingual communities. From a pedagogical perspective it describes a pedagogical approach whereby teachers build bridges from these language practices and the language practices desired in formal school settings. Our focus in this book is on pedagogy, by which we mean the art, science, method, and practice of teaching. the official language of instruction of the class. We put forward a translan- Bilingualism is the norm in translanguaging classrooms-regardless of guaging pedagogy that shows educators how to leverage, or use to maximum advantage, the language practices of their bilingual students and communities while addressing core content a trate this pedagogy in action du language development standards. We illus sent the kinds of diversity we find among students, teachers, language policies, with three particular cases that together repre program types, and grade levels in schools. As you read we encourage you to think about the actual language practices of your students relative to the offi- cial language policy of your school. 2012a, 2012b. For more on translanguaging, see Garcia and Li Wei, 2014. See also Lewis, Jones, and Baker TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS 3 Carla's Elementary Dual-Language Bilingual Classroom Carla teaches a 4th-grade dual-language bilingual class in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where all of the students are from Spanish-speaking homes. This elementary school program aims for bilingualism, biliteracy, and aca. demic achievement in two languages. Carla was born in Puebla, Mexico, and she came to New Mexico at the age of 10 with her family. She is bilingual and studied Spanish in high school and at college as she pursued her bilingual education certification, Most of Carla's students are Spanish-speaking bilinguals, though their in- dividual profiles are very different. Moiss, for example, emigrated from Mex- ico to the United States two years ago, and is considered a newcomer. Moiss is officially designated as an ELL, but we refer to him as an emergent bilingual Though Moiss is developing his Spanish and English practices in Carla's classroom, he prefers speaking Spanish. Ricardo, like Moiss, is considered a newcomer, and is officially designated ELL. Ricardo is in the process of learn- ing English. At home he speaks Spanish and Mixteco, the language he spoke with his family and community in Mexico. At different points on the bilin- gual spectrum are Erica and Jennifer, who were both born in the United States. Erica prefers to speak English, though her family does speak some Spanish at home, while Jennifer, a more experienced bilingual, feels comfortable using both languages to carry out academic tasks. As we can see, not all of Carla's students are classified as ELLs or are, as we call them, emergent bilinguals. Her students' bilingual performances are varied and the students have a wide range of strengths within and across languages. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) have been adopted by the state of New Mexico, and New Mexico is, at the time of this writing, part of the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Career (PARCC) con- sortium. Carla's instruction must therefore be aligned with the CCSS and stu- dents must demonstrate proficiency on PARCC assessments. New Mexico is also a member of the WIDA consortium. Carla's instruction for emergent bilinguals who are officially designated as ELLs must therefore align with the WIDA English language development (ELD) standards, and these students must demonstrate English language proficiency on the test developed by WIDA, Assessing Comprehension and Communication in English State-to- State (ACCESS) for ELLs. At this time, New Mexico also gives their emergent bilinguals the LAS Link Espanol, a diagnostic assessment of Spanish language development. Furthermore, all students in the dual-language bilingual pro- gram must demonstrate learning relative to the goals of bilingualism and bi- literacy. This school district uses the Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA) to assess reading in English and the Evaluacin del desarrollo de la lectura (EDL) to assess reading in Spanish. Although Carla was always comfortable translanguaging and saw its value in intercultural communication, she was taught never to use it for instruction. We use the term dual-language bilingual education intentionally, In New Mexico, this type of bilingual program is often referred to as one-way dual language education. In some educa tion districts, this type of program is referred to as a developmental bilingual education program, or as a developmental-maintenance bilingual education program. We do not use the term "one- way" because in practice we find tremendous variation in the ways that emergent and experi- enced bilingual students from the same" language background use languages in their everyday lives. We also include the word bilingual, which has largely disappeared from discussions about dual language education in response to the backlash against bilingualism and bilingual educa. tion. In fact, it is not uncommon to hear bilingual educators say that dual language education is not bilingual education, a stance with which we disagree. Our use of bilingual emphasizes that dual language education is bilingual education TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CONTEXTS AND PURPOSES Her teacher education program in bilingual education advocated that unless there was a clear and separate space for Spanish, English would take over in- struction and Spanish would not be maintained. In studying the dual language model she was told that teachers were never to put the different language English and Spanish never appeared together, dedicating different parts of the practices alongside each other. She was taught to make sure that writing in room to the two languages. At the beginning of her career, she taught strictly dents when they spoke the "wrong" language at the "wrong" time. She never in Spanish in the morning and in English in the afternoon, and corrected stu. brought multilingual resources into the classroom-she used Spanish resources during Spanish time and English resources during English time. When Carla discovered the concept of a translanguaging pedagogy for the first time, she questioned and resisted it. However, she quickly realized that were always using features from Spanish and English to make meaning, albeit stop. Carla decided to bring the students' language practices to the forefront other in Spanish, and when Carla approached, the discussion would simply and build on them in the classroom. Instead of "policing" which language was used where, she encouraged students to use their entire language reper- toires to learn and demonstrate what they had learned. Though she main- tained an official space for English and an official space for Spanish to provide the appropriate opportunities for language development, she now allowed some flexibility in student language use. At the center of Carla's literacy and language instruction during her (bi)- literacy block is the sharing of human experiences, and especially those of the neighborhood and land, el barrio y la tierra, which she sees as interrelated. The experiences of the New Mexico barrio where Carla's school is located are deeply connected to the tierra because many of her students' parents are farm workers. Carla introduced a translanguaging space into her dual-language bilingual classroom through what she called "Cuntame algo," which she de scribes as a time for bilingual storytelling when a translanguaging literacy ac- tivity takes center stage. Her instructional unit, Cuentos de la tierra y del barrio, focuses on stories of how students, families, and the local community are tied to their land and, by extension, to their traditions. Students discuss cuentos written by Latino bilingual authors about land and traditions, as well as those told to them by family and community members, including abuelitos and abuelitas, grandparents whom Carla invites to her classroom. They also dis cuss the video clips that they watch, as well as their own experiences, and those of barrio residents, with the land. Stephanie's High-School Social Studies Class Stephanie is an 11th-grade social studies teacher in New York City, and En- glish is the official language used for instructional purposes in her classroom. Thus, Stephanie's classroom provides an example of a translanguaging class- room in an English-medium context. She is of Polish descent and, though she knows some Spanish words that she has learned from her students, she does not consider herself bilingual. Stephanie was trained as a history teacher but found that once she entered the classroom she also had to teach content area literacy. The linguistic diversity in Stephanie's English-medium classroom is rich. few of her students are officially designated as ELLs. Some of these emergent who perform differently in language and literacy in Spanish and English. A bilinguals (to use our preferred term), like Noem, are newcomers with solid Most, though not all, of Stephanie's students are Spanish-speaking Latinos a Learning TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS educational backgrounds and strong oracy and literacy in Spanish. Other newcomers, like Luis, have had interrupted or poor schooling in the countries they came from and struggle with literacy and numeracy in any language. Other emergent bilinguals, like Mariana, have received most or all of their education in the United States but were labeled as ELLs when entering school and have yet to test out of this status. Although Mariana is now classified as long-term English language learner (LTELL), she generally uses English at school; in fact, many of her teachers do not even realize considered an ELL. is still officially versity among Stephanie's "English-speaking students. Most of her students It is important to emphasize that we also find considerable linguistic di- are bilingual Latinos, but because they are not designated as ELLs their bilin. gualism tends to go unnoticed. Stephanie, however, knows that these students have a wide range of experiences with oral and written Spanish and English. Some, like Eddy and Teresita were born in the United States and have dif- ferent degrees of comfort with using Spanish. The few students who are not Latinos in her class are African Americans, some from the Anglophone Carib- . bean, and their English also includes features that are not always considered standard or appropriate for academic purposes. In 2010, New York State adopted what it called the P-12 Common Core Standards (CCLS) for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/ Social Studies, Science and Technical Subjects, and for Mathematics. These are based on the CCSS, with a few additions. This means that Stephanie's instruc- tion must be tion must be aligned with New York's CCLS and that all students in her class have to demonstrate proficiency on assessments aligned to the CCLS. In addi- tion, New York State has standards for science and social studies in place. Aca- demic achievement tests for graduation (the Regents Exams) are translated into the five most common languages of students-Chinese, Haitian Creole, Korean, Russian, and Spanish-although students also have to pass the English Regents exam. Furthermore, all students who are designated as ELLs in New York State must demonstrate English language proficiency on the New York State English as a Second Language Achievement Test (NYSESLAT). New York launched the Bilingual Common Core Initiative (BCCT) in 2012, which is intended to help all teachers differentiate CCLS language arts instruc- tion and assessment for the bilingual students in their schools. At the heart of this initiative are the New Language Arts Progressions (NLAP) and Home Lan- guage Arts Progressions (HLAP). Unlike the English language proficiency and development frameworks used by other states, the BCCI explicitly acknowl- edges that students' home languages are a valuable resource to draw on and that the new and home languages are inextricably related in learning. These progressions are flexible and can be used by teachers as a first step toward un- derstanding how students use their new and home languages to learn. In fact, emergent bilinguals at the early stages of ELD are allowed to demonstrate their understanding of content in their home languages. Teachers can use formative assessments to approximate the new and home language development levels of their students along these progressions (Velasco & Johnson, 2014). When she first started teaching, Stephanie realized quickly that her stu- dents were capable of thinking critically and understanding deeply. But she also knew that the English language through which the content was taught was a real challenge for some of her students. How could she work with the students' strengths and creativity and make the content comprehensible? When she learned about translanguaging, she realized that she could use trans- languaging strategies with her students to leverage the many different lan- guage resources in her class. Without knowing it, she had already set up her classroom in ways that made it possible to capitalize on translanguaging. She had always organized students into groups that had mixed strengths so they 5 TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CONTEXTS AND PURPO learning activity. interdisciplinary, units. In these groupings she noticed that peers helped each could help each other in the project-based activities of her thematic, often kind of translanguaging interaction to enable all students to engage with the other using Spanish as well as English. She realized she could encourage this Since learning about translanguaging, Stephanie has made a strong effort to build a robust multilingual ecology in which all her students can thrive. with bilingual staff members and student volunteers to translate and create For example, although her classroom is not officially bilingual, Stephanie works multilingual materials and actively seeks out Spanish language resources Stephanie also has a shelf full of bilingual dictionaries and picture dictionaries that students can use at any point in the lesson. She has been successful in securing iPads, which newcomers use frequently to access the Spanish version of their history textbook, and she also uses apps like Google Translate. different content areas. While schools separate topics into categories like so- Stephanie is passionate about helping her students see connections across cial studies or science, Stephanie believes that one cannot be understood with out the other. Thus, many of Stephanie's units focus on history but bring in interdisciplinary connections. For example, one of Stephanie's interdisciplin ary units, Environmentalism: Then and Now, is a historical study of the US environmental movement. Students learn about the history of this social movement by reading their textbooks and many supplemental readings from websites, newspapers, and magazines. They also listen to podcasts and radio interviews, watch clips from documentaries, and look at visual art, Stephanie also invites in community experts, for example the 11th-grade science teacher and the leader of a local nonprofit. Though the textbook does not focus heavily on the environmental move- ment, Stephanie places this movement within a larger historical context, from its beginnings during industrialization, to social action campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s, to today's political conversation on climate change. Because she knows that her students excel when their understanding is brought home," the unit culminates in students designing a plan of action that would make the school or local community more environmentally sound and/or sustainable. Justin's Role as a Middle-School English as a Second Language Teacher Justin provides push-in ESL services in English-medium middle-school math and science classrooms in Los Angeles, California. Justin speaks English and Mandarin Chinese (following two years of studying Chinese in Shanghai). His students are speakers of many languages, including Spanish, Cantonese Chi nese, Mandarin Chinese, Korean, Mandingo, Tagalog, Vietnamese, and Pular (Pula). The students who speak Fula and Mandingo also speak French, the che lonial language of West Africa. Because there are multiple speakers of Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, French, Tagalog and Vietnamese in this classroom Justin groups students according to their home languages and mixed English language abilities. But there is only one Korean student in the class, Jeehyae. Although most students in Justin's class have at least one other student with whom they can collaborate to make meaning of the texts, there is great diversity among students, even among those with the same language back- ground. For example, Yi-Sheng arrived recently from Taiwan. Unlike some of the other students from mainland China, Yi-Sheng has not received any in- struction in using Latin script, so she needs lots of writing practice. Pablo came not from Mexico, the country of origin of most of the Latino students in the class, but from Argentina, and attended private English after-school classes before coming to Los Angeles. Fatoumata came from Guinea not long ago. PURPOSES FOR TRANSLANGUAGING 7 She had only gone to school irregularly in Africa, so she struggles with literacy in French, the language of instruction in Guinea. She is not the only Pular- speaking student in Justin's classroom, although West African children in the class often speak to each other in French, the colonial language. California has adopted the CCSS, and is a member of the Smarter Balanced consortium as of this writing, which means that Justin's instruction needs to align with the CCSS and that all of his students need to demonstrate profi- ciency on the Smarter Balanced assessments. California has also developed the Common Core en Espaol, which is a translation of the CCSS from English into Spanish that also addresses concepts that are specific to Spanish language and literacy. All students in California who are officially designated as English learners (ELS) have to demonstrate proficiency on the state-developed Cali- fornia English Language Development Test (CELDT), based on the California ELD Standards. Justin's role in the content classrooms has been to support the students so that they could meet the demands of the California CCSS and the California ELD Standards. He often obtains supplementary written material in the lan- guages of the students and brings it to class. He uses Google Translate to write worksheet instructions in the students' languages. Justin also encourages stu- dents to use iPads to look up words and translate passages, and he often uses the iPad to make himself understood in students' languages. Because Jeehyae is the only Korean student in the class, Justin spends lots of time using Google Translate, trying to make the material accessible to her. He also makes sure to help her translanguage on her own, telling her to use her intrapersonal inner- speech to brainstorm, and he encourages her to prewrite and annotate texts in Korean. Though Justin won't understand what Jeehyae writes, he makes it clear that the language she brings with her is useful and necessary to her learn- ing and her development of English. Justin also often seeks help from other Korean-speaking students in the school. Because students in this classroom often write in their home languages, Jechyae has discovered that she knows some of the Chinese characters the Cantonese and Mandarin speakers use because she learned some of them in her Korean school. Although these three teachers' classrooms are different with respect to their students' language practices, the official language policy in their classes, and the different state-mandated standards, they all use translanguaging in their classrooms. It is important to remember that translanguaging classrooms can be of any type-bilingual (whether dual language or transitional) or English-medium (whether ESL programs or mainstream classrooms). Translanguaging also can be used by any teacher, whether bilingual or monolingual; whether an ele. mentary, middle school, or high school teacher; whether officially a language teacher (English or a language other than English) or a content teacher. PURPOSES FOR TRANSLANGUAGING The translanguaging pedagogy we put forward in this book is purposeful and strategic. We identify four primary translanguaging purposes: 1. Supporting students as they engage with and comprehend complex con- tent and texts 2. Providing opportunities for students to develop linguistic practices for academic contexts 3. Making space for students' bilingualism and ways of knowing 4. Supporting students' bilingual identities and socioemotional development TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CONTEXTS AND PURPO That is, when teachers effectively leverage students' bilingualism for leam. These four translanguaging purposes work together to advance social justice. ing, they help level the playing field for bilingual students at school. Supporting Student Engagement with Complex Content and Texts When we make space for students to use all the linguistic resources they have developed to maneuver and navigate their way through complex content, myriad learning opportunities open up. Rather than watering down our in- struction, which risks oversimplification and robs students of opportunities to engage in productive grappling with texts and content, translanguaging better enables us to teach complex content, which in turn helps students learn more successfully. Moll (2013) describes the importance of working with bilingual students in what he calls the bilingual zone of proximal development, in which as sistance is offered to students bilingually to mediate their learning and stretch their performance. As we will see, there are many ways of doing this. Students can work in home language groups to solve difficult problems or analyze a complex text. They can talk to one another about content using their own language practices in ways that help them better understand that content Because learners develop knowledge interpersonally, it is important for them to enter into relationships with others whose language repertoires overlap with theirs so that they can deeply understand the classroom texts. Knowledge is also developed intrapersonally, as students try out new concepts and new lan- guaging in internal dialogue and private speech. Because bilingual students have a voice that includes their home languages, they need to be encouraged to draw on all of the resources for learning in their linguistic repertoires. Unfortunately, we don't often find LOTE being used as resources for learn- ing challenging content and engaging with complex texts in U.S. classrooms serving bilingual students. Instead, teachers generally tell students to only use English; bilingual students and particularly emergent bilingual students) often learn that only English counts. This is especially the case for Spanish speaking students who are told: "speak English," "don't speak Spanish"; "think in English," "don't think in Spanish. As a result, Latino students often learn practices that are not to be used in academic environments. In so doing, bic to see Latino cultural and linguistic practices only as home and community lingual Latino students are often silenced, using only part of their linguistic that are important to them in acquiring content knowledge. Leveraging trans- repertoires and accessing only a small portion of the adults, peers, and texts languaging interpersonally and intrapersonally can help bilingual students overcome this silence and engage with and understand complex content and texts. whose language practices align with those used in school, understand challeng Schools need to find ways of ensuring that all students, not just those ing content and texts. Translanguaging enables educators to more equitably provide opportunities for students to engage with complex material, regard- less of language practices. In this way, translanguaging at school is inextrica- plan that Stephanie designed for her 11th-grade English-medium class, stu dents were asked to analyze some statistics about air pollution and asthma, For example, in a lesson from the Environmentalism: Then and Now unit areas, as well as make a connection to the previous day's lesson on the Clean issues that disproportionately affect Latinos and other residents of urban nos, as well as the map in Figure 1.1 that illustrated which counties did not Air Act of 1970. Stephanie included statistics about asthma rates among Lati- bly linked with social justice. meet standards for air pollutants. URPOSES FOR TRANSLANGUAGING Figure 1.1 Counties that do not meet standards for air pollutants, based on U.S. Environmental Pro- tection Agency data. (Retrieved from http://www.nrc.org/health/effects/latino/english/latino_en.pdf) After analyzing the two different forms of data, Stephanie asked students, organized into small groups, to come up with some kind of connection-how did these two sets of data tell a story about the issue? Although the official language of instruction was English, Stephanie told students that they could discuss the statistics, the map, and the answers to her question in English and/ or Spanish and could write their responses in English and/or Spanish. She also told students they were expected to share with the whole class. This vignette shows us what happened next: After examining the map and discussing it with his group, Luis, who recently came to the United States from El Salvador, shared in Spanish with the whole class that "las reas oscuras estn cerca de ciudades como Nueva York y Los ngeles. Muchos Latinos viven en esas ciudades." [The dark areas are near cities like New York and Los Angeles. A lot of Latinos live in those cities.] Mariana, who was in Luis' group, eagerly added: "Yes, Latinos live in the dark areas on the map. Like in New York and Los Angeles." Some students nodded and others wrote down the comment in Spanish or English next to their own in their notebooks, Eddy added in English that "cities have more pollution than other places." Stephanie then summed up the two comments in English, restating, "It sounds like what you're saying is that if most Latinos live in cities, and cities have more air pollution than rural or suburban areas, that this might be a cause of increased asthma in Lati- nos." Students nodded and voiced their agreement. The kind of linguistic flexibility we see here-using both languages to dis- cuss, negotiate, and finally write down connections; sharing out their learning in both languages-helped all of the students in Stephanie's classroom en gage with English texts, synthesize a complex issue, and demonstrate their learning. As we can see from Luis', Mariana's, and Eddy's comments, the trans- languaging they had done in groups allowed them to access the content, de- spite the fact that, for example, Luis was a less experienced English user than Eddy. Without translanguaging, which was both an explicit part of Stephanie's TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CONTEXTS AND PURPOSES instructional design and a naturally occurring phenomenon among students in their small groups, this kind of intellectually rich conversation would not have taken place. Carla also uses translanguaging to engage her bilingual students with instruction is biliteracy, translanguaging in her classroom looks quite different complex content and texts. However, because an important goal of Carla's from what we saw in Stephanie's class. During Cuntame algo, students en gage in studies of Latino bilingual authors who translanguage to make experi- ences and characters come to life. Students are encouraged to use all their language practices, which include English and Spanish, to discuss and evalu. ate these stories. Sometimes texts are chosen with English as the main lan- guage but other times Spanish is the main language of the text. Besides read. ing and discussing, students are encouraged to design texts (orally and in writing) that reflect the dynamic bilingual language use of communities, both when they communicate among themselves and when they communicate with others who may not share their language practices. For example, in a lesson from her unit on Cuentos de la tierra y del barrio, Carla and her students used the Cuntame algo space to do a read-aloud and shared reading of Three Wise Guys: Un cuento de Navidad by Sandra Cisneros: Carla read en voz alta: The big box came marked do not open till xmas, but the mama said not until the Day of the Three Kings. Not until Da de los Reyes, the sixth of January, do you hear? That is what the mam said exactly, only she said it all in Span- ish. Because in Mexico where she was raised, it is the custom for boys and girls to receive their presents on January sixth, and not Christmas, even though they were living on the Texas side of the river now. Not until the sixth of January Carla engaged students in telling her about el Da de los Reyes. Some of the stu- dents did so in English, some in Spanish, and some in both languages. To get students to engage with the text in a deeper, more nuanced way, she set forth the following activity: Carla took [a] large sheet of chart paper and drew la corriente del Ro Grande. On one side she wrote a sentence the author had written in English. She then asked the groups to translate into Spanish what the author would have said if she were on the Mexican side of the Ro Grande. While they worked, one group grewe louder. Carla asked what was the matter and one of them said: "Maestra, es que mi familia on the other side also speaks English. And on this side tambin habla- mos espaol." A whole class discussion then ensued about bilingual language practices in the borderlands and when and how to use them. Rather than stop with simple comprehension of the story, the shared reading of this class was the jumping-off point for students' engagement in Cisneros' book. Carla's explicit focus on the language of the book, and how different nect with the story on a much deeper level. Carla also tapped into students' contexts and characters use different language practices, helped students con bilingualism, asking them to translate sentences from the book from one language to the other. This not only helps students with the close reading of a text; it also helps them to learn new vocabulary and make connections between their languages. Carla encourages students not to produce a literal translation, but to transform the text as they renderit in the lanmage PURPOSES FOR TRANSLANGUAGING 11 When students came to the realization that their familia on both sides of the border spoke both languages, they began a larger, critical conversation about language practices in borderlands like Texas. This connection and intel- lectual exchange would not have been possible without the translanguaging that students experienced in the Cuntame algo space. Similar to Stephanie's lesson, Carla's explicit use of translanguaging helped her students engage more deeply with a text. Providing Opportunities for Students to Develop Linguistic Practices for Academic Contexts "Academic language" is a term we encounter over and over again. Following Valds (2017), we wish to reframe this term, imagining that what some call academic language is simply one of many forms of languaging that students must take up to be successful in school. Translanguaging can help us teach the types of linguistic practices that are deemed appropriate for academic con- texts. For example, translanguaging supports bilingual students' ability to use language to gather, comprehend, evaluate, synthesize, and report on infor- mation and ideas, using text-based evidence, as the CCSS (or any other 21st- century standards) require. Translanguaging also helps students develop the ability to use language to persuade, explain, and convey real or imaginary experience. Because translanguaging requires collaboration, it also bolsters students' ability to use language socially through cooperative tasks, another language requirement of the CCSS. Encouraging students to use all the features of their language repertoires, including lexical (words), syntactic (grammar), and discourse (larger chunks of text that hang together as a unit) features, gives them something on which to "hang" new linguistic features--what Garca has called translanguaging "hooks." When learning a new language, translanguaging can help students make connections and comparisons, ask deep questions, and practice and play with language. Translanguaging can also demystify what some call academic language, showing students that using the highly valued language practices for academic purposes is actually just adding another set of language features and practices to their growing repertoires. When translanguaging is not allowed in schools, bilingual students are placed at a disadvantage because they are assessed on only a portion of their linguistic repertoires and are taught in ways that do not fully leverage their language resources. Furthermore, the new language features that bilingual stu- dents learn at school do not always become part of their own linguistic reper- toires, continuing to represent a "second" language that belongs to others. Thus, this translanguaging purpose is also linked to social justice because it creates the space for fair educational and assessment practices for bilingual students-without the linguistic prejudice that accompanies accepting only the linguistic features of standard English--the language of power. The following example from Stephanie's lesson on air pollution illustrates how she and her students use translanguaging to strengthen students' linguis- tic practices for academic purposes. The focus is on the asthma rates among Latinos, specifically Puerto Ricans. Stephanie projected the following statistics up on the SMART Board and asked one student to read through them aloud: Puerto Rican Americans have twice the asthma rate as compared to the overall Hispanic population. Hispanics are 30 percent more likely to visit the hospital for asthma, as compared to non-Hispanic Whites. TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOMS: CON pared to non-Hispanic Whites. pared to non-Hispanic Whites. Puerto Rican children are 3.2 times more likely to have asthma, as com Hispanic children are 40 percent more likely to die from asthma, as com- of the English used. Luis said: "Maestra no entiendo" (and pointed to the phrase After the student read the statistics, Stephanie checked the class' comprehension "more likely"). Stephanie asked students to translate it for Luis, and this turned Others as "ms como" (more like). Finally, Stephanie asked Luis to use the trans- into a heated discussion. Some translated it as "ms me gusta" (I like it more) Stephanie annotated the text on the SMART Board with this Spanish phrase. Now lating app on a class iPad, and he immediately came back with "ms probable." all students in the class knew not only what it meant in English, but also how to say it in Spanish This simple classroom vignette illustrates two important points. First, bilin- gual students may think they know the meanings of a word or phrase (e. more likely) in an academic text because they know each of the words in other students' existing language practices are valued and channeled into learning contexts, but this is not always the case. This vignette also illustrates ways that new practices, such as those deemed important in academic contexts. Because Stephanie is not a Spanish speaker, she encourages her students to help one another and to use resources such as translation apps to better understand this and other texts in English. By annotating an English text with a Spanish phrase, Stephanie is also helping students grow as bilingual and biliterate peo- ple, even if she herself is not bilingual and this is not a "bilingual" class. Furthermore, Stephanie encourages her African American students to think about differences between ways they use language among their friends and at school. She often discusses language in hip hop and compares it to