Question: Read Classroom Glimpse. Discuss stress, rhythm, pitch, and intonation based on the tale in the classroom 2 Language Structure and Use Learning Outcomes After reading

Read Classroom Glimpse. Discuss stress, rhythm, pitch, and intonation based on the tale in the classroom

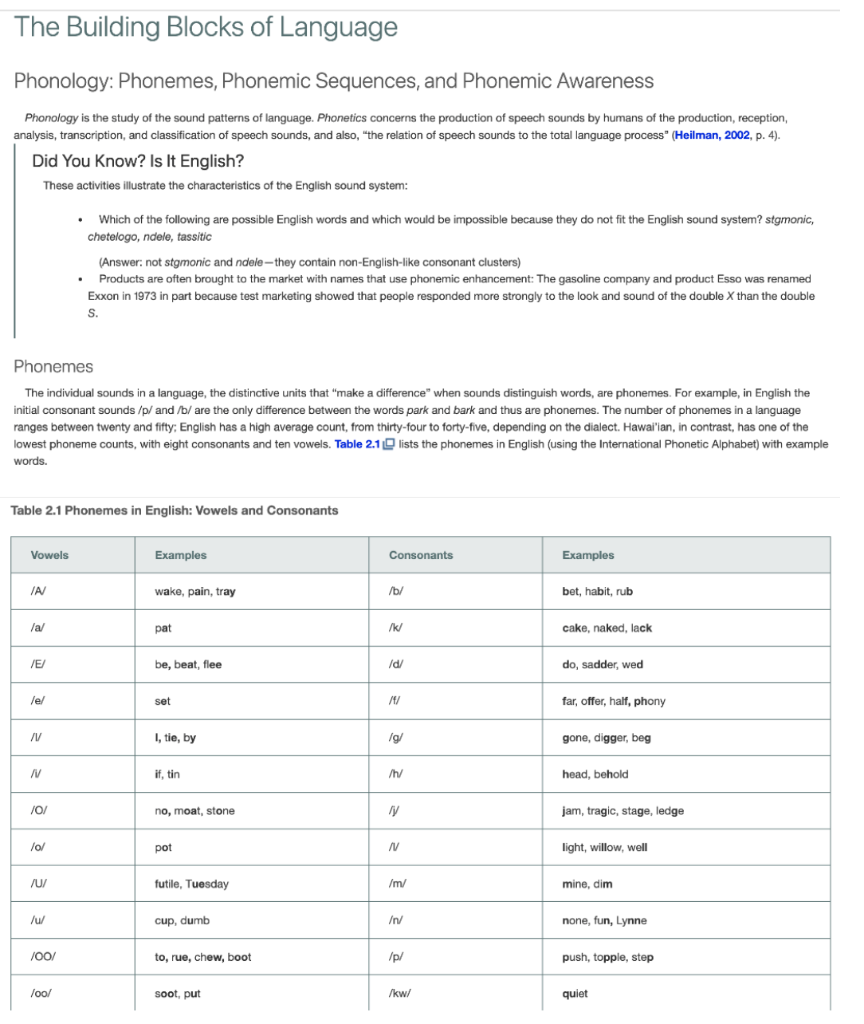

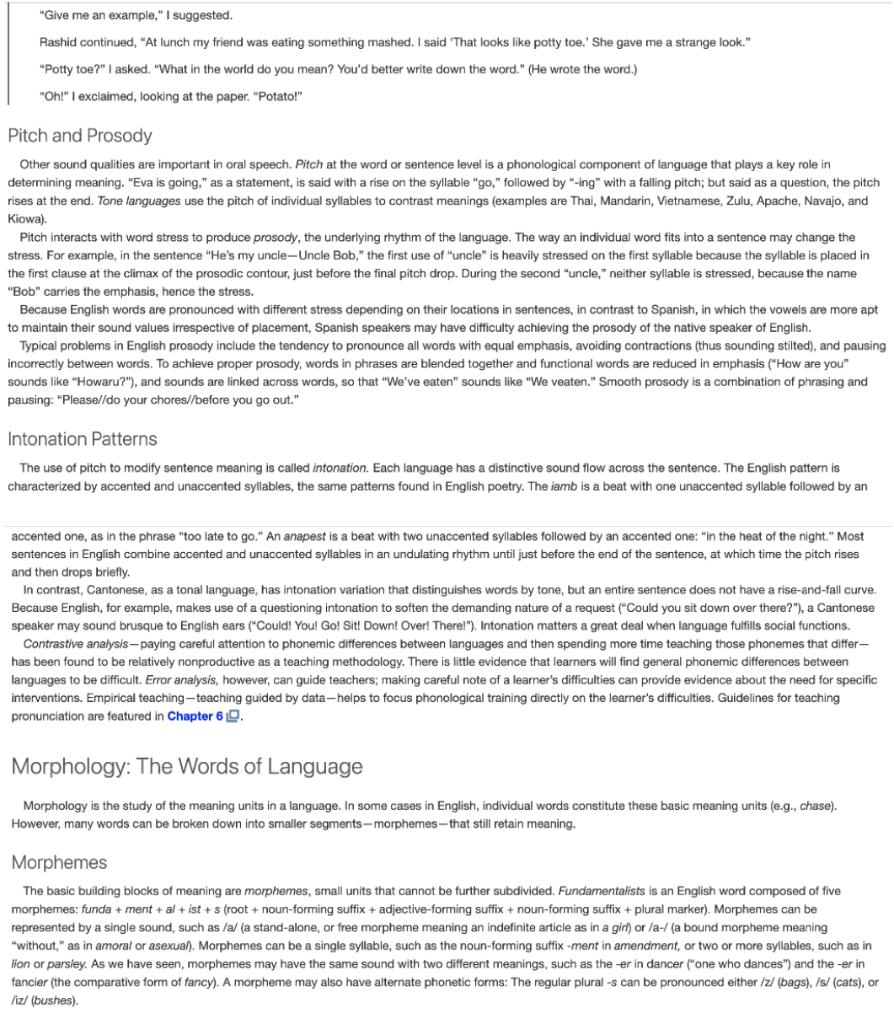

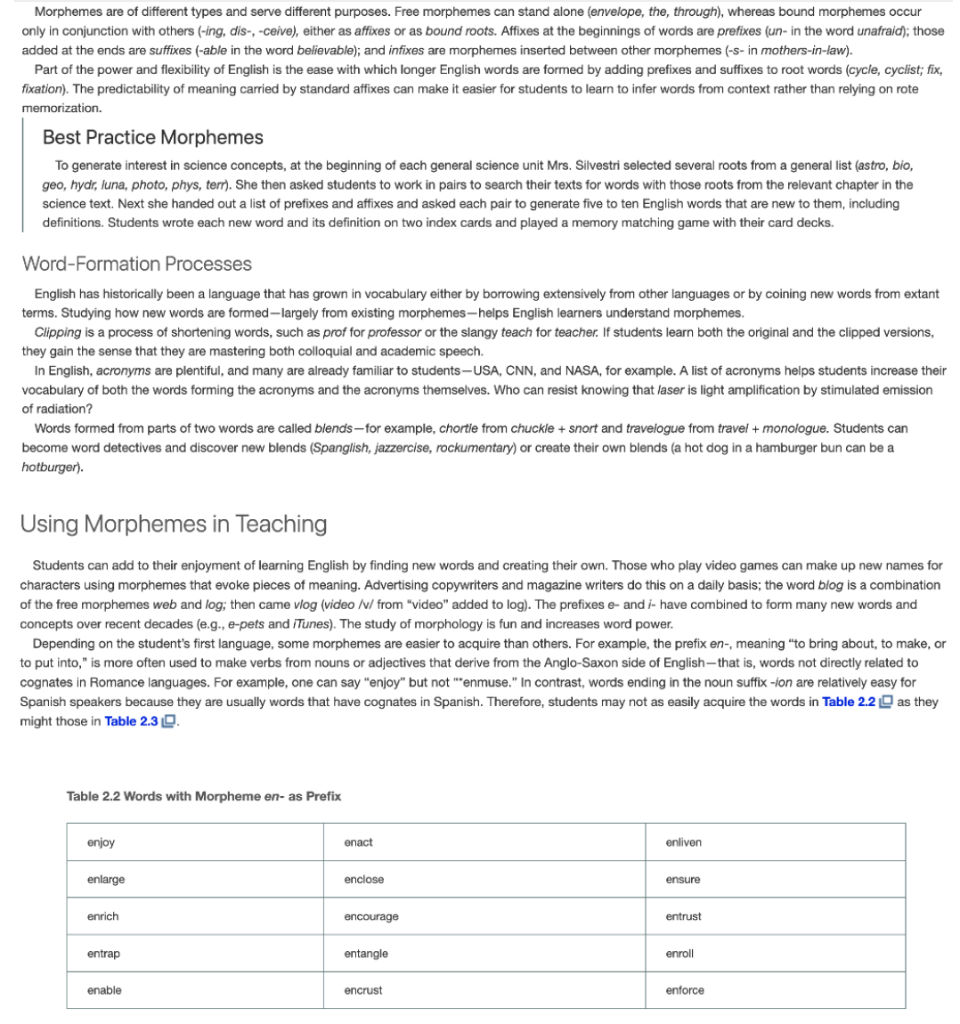

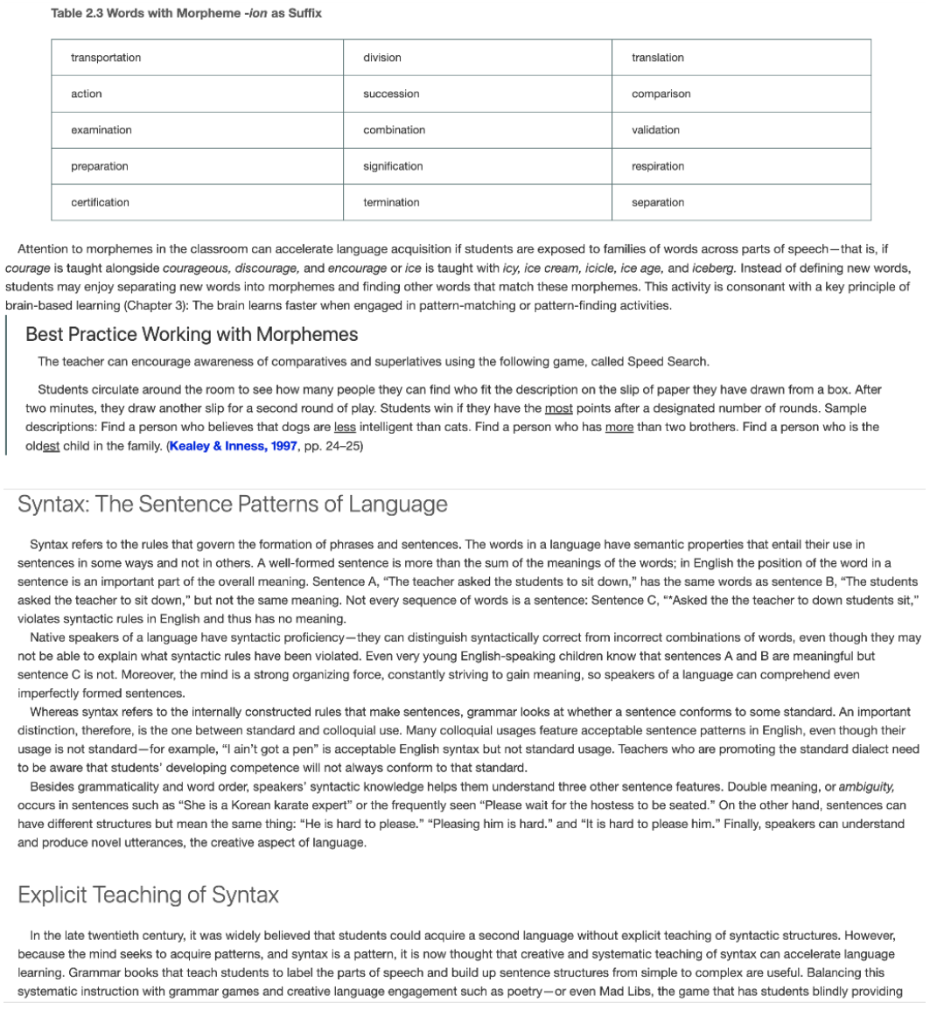

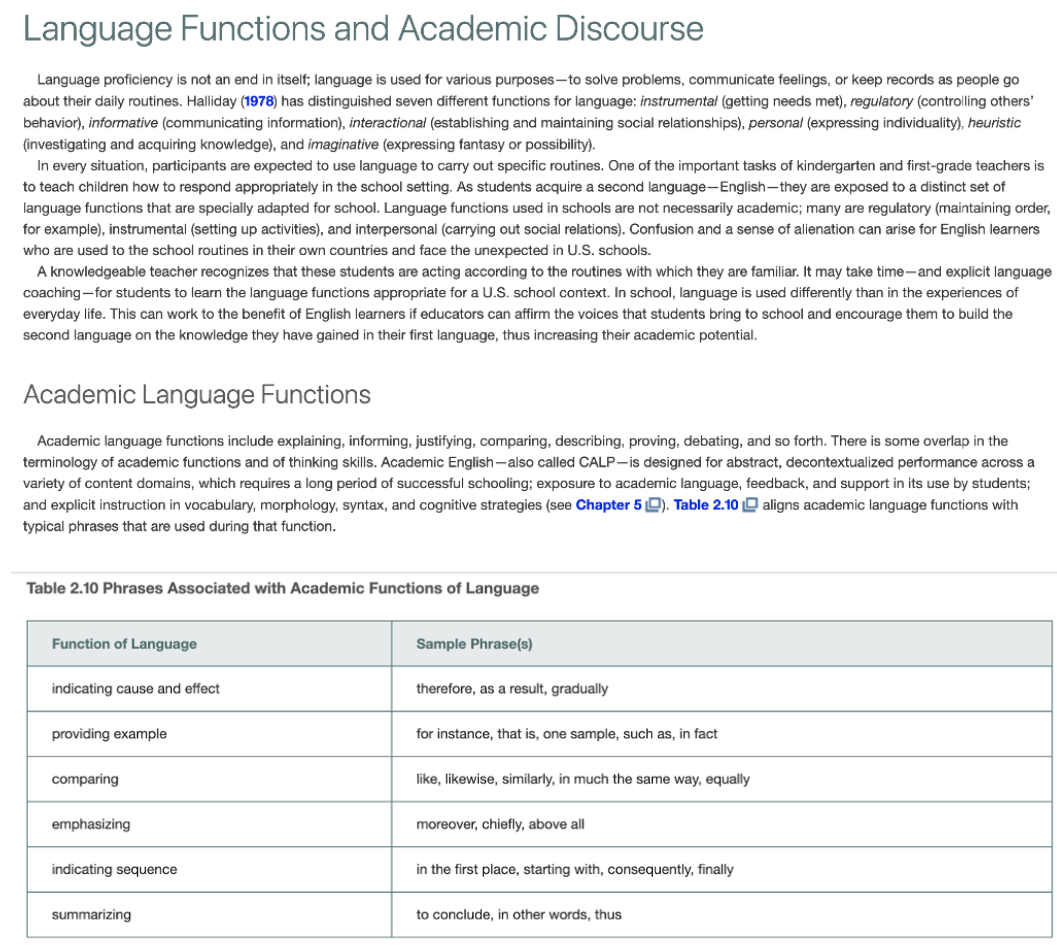

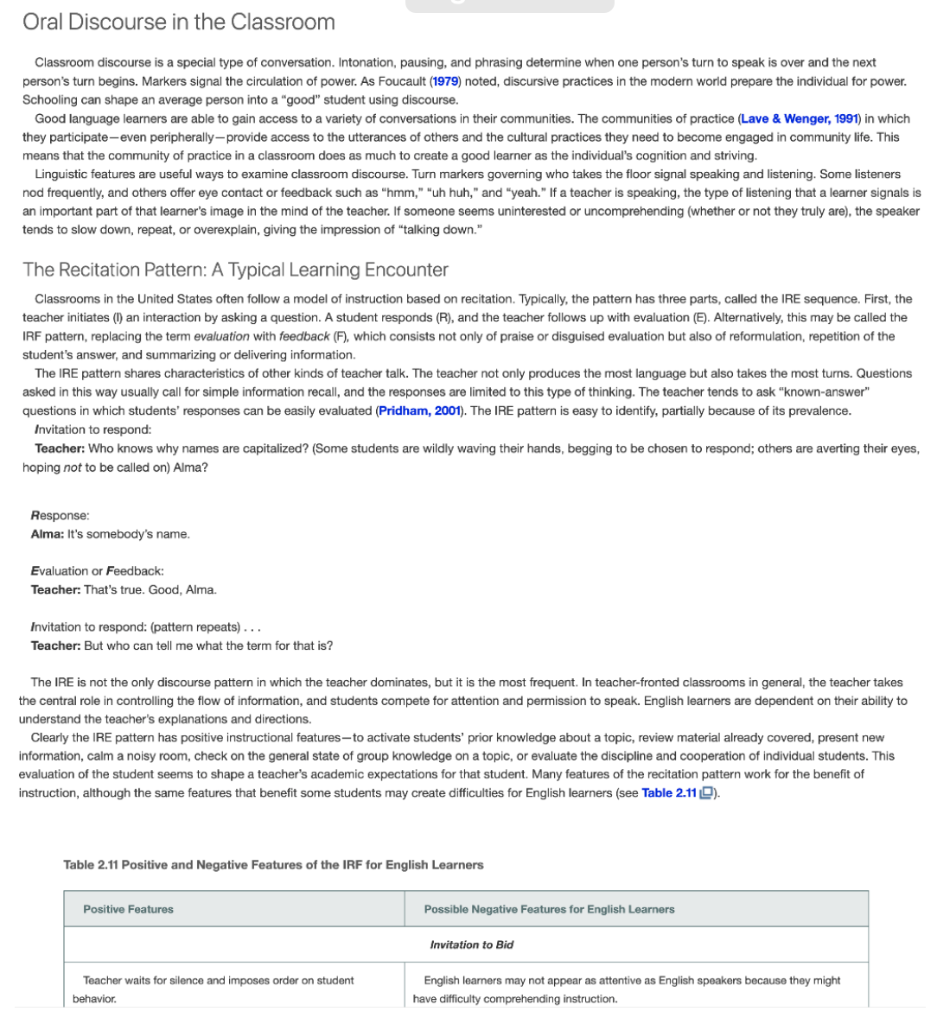

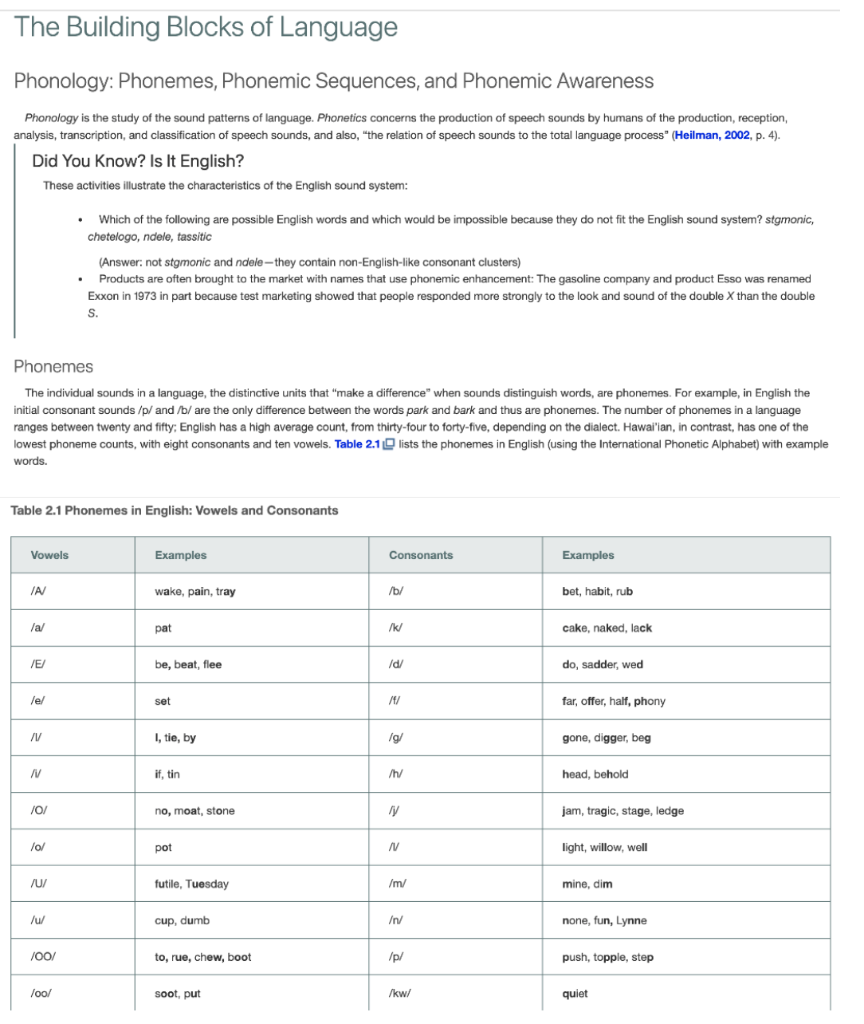

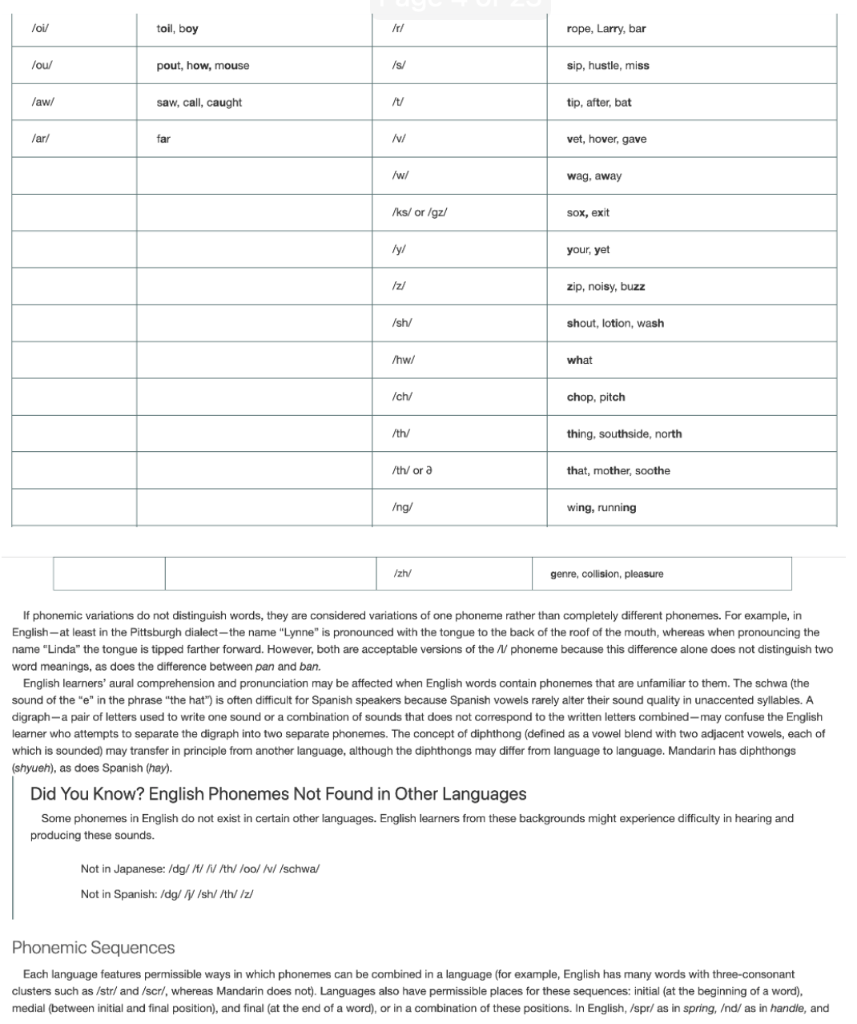

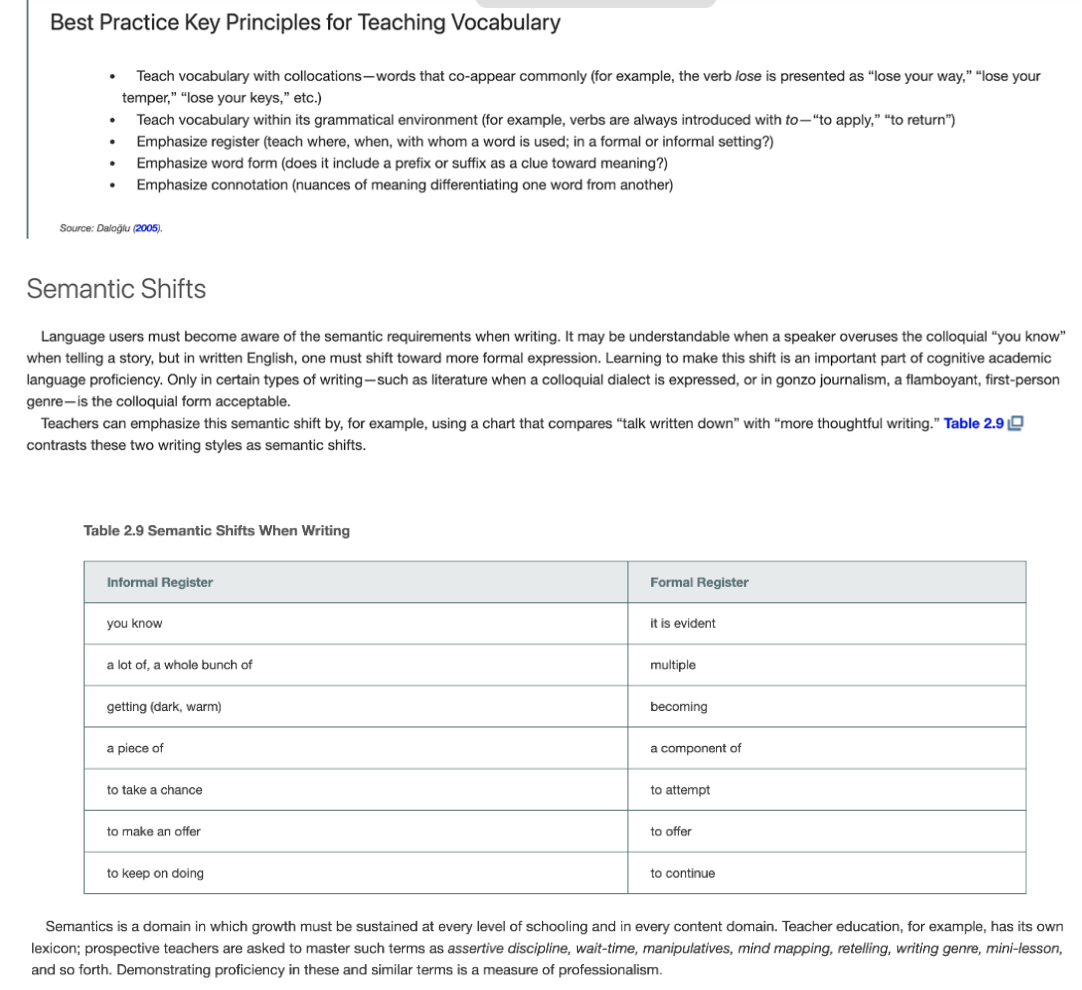

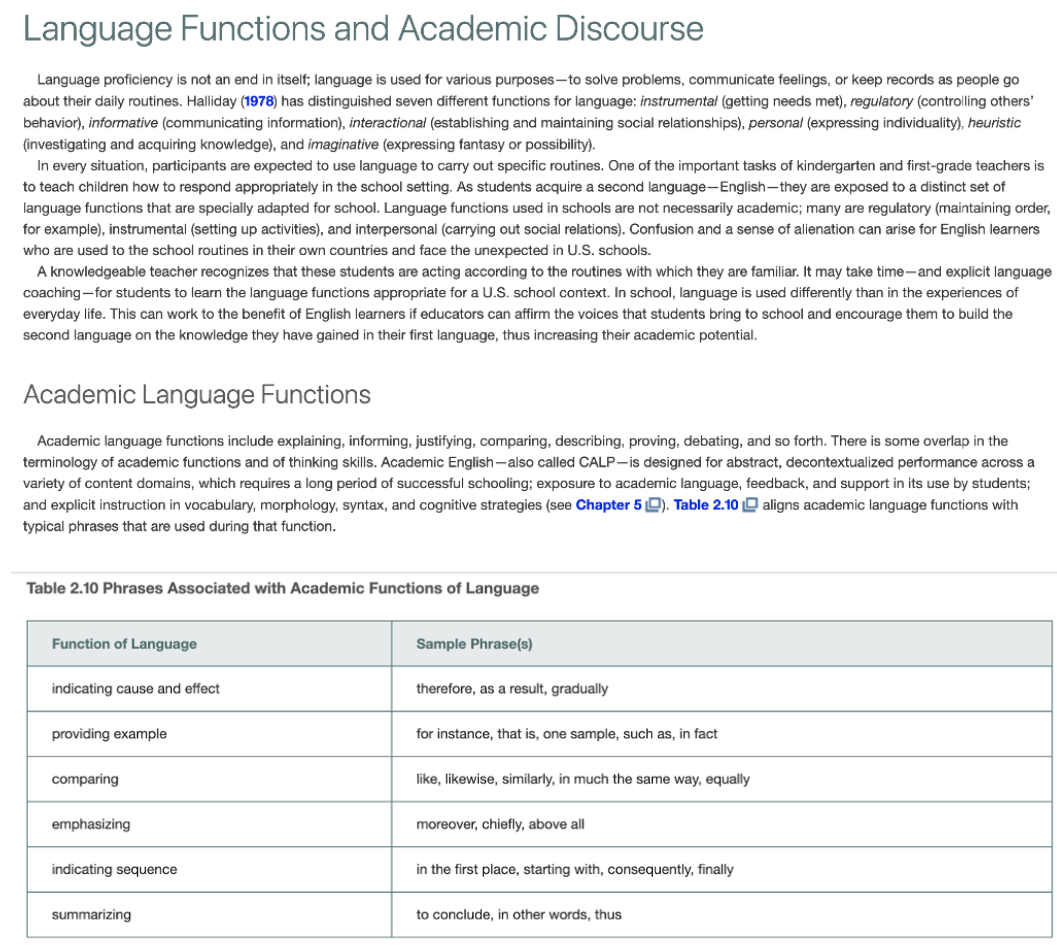

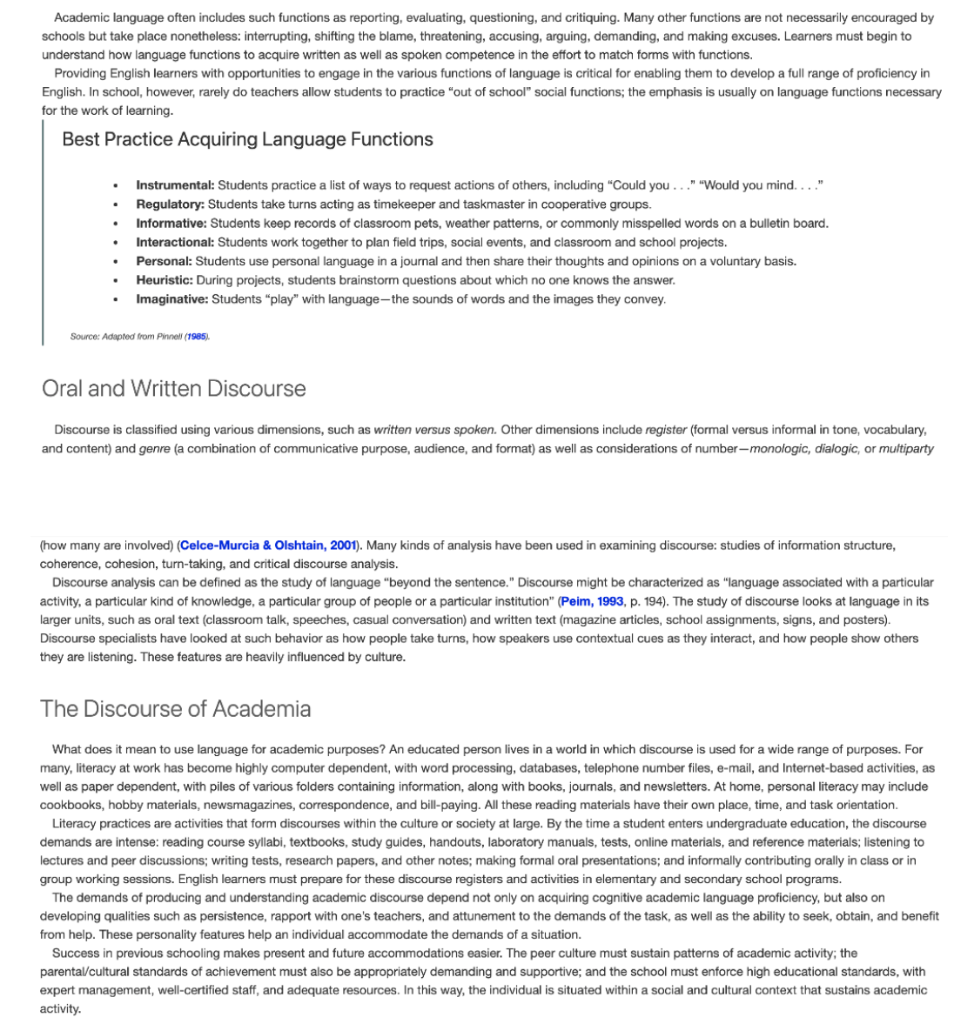

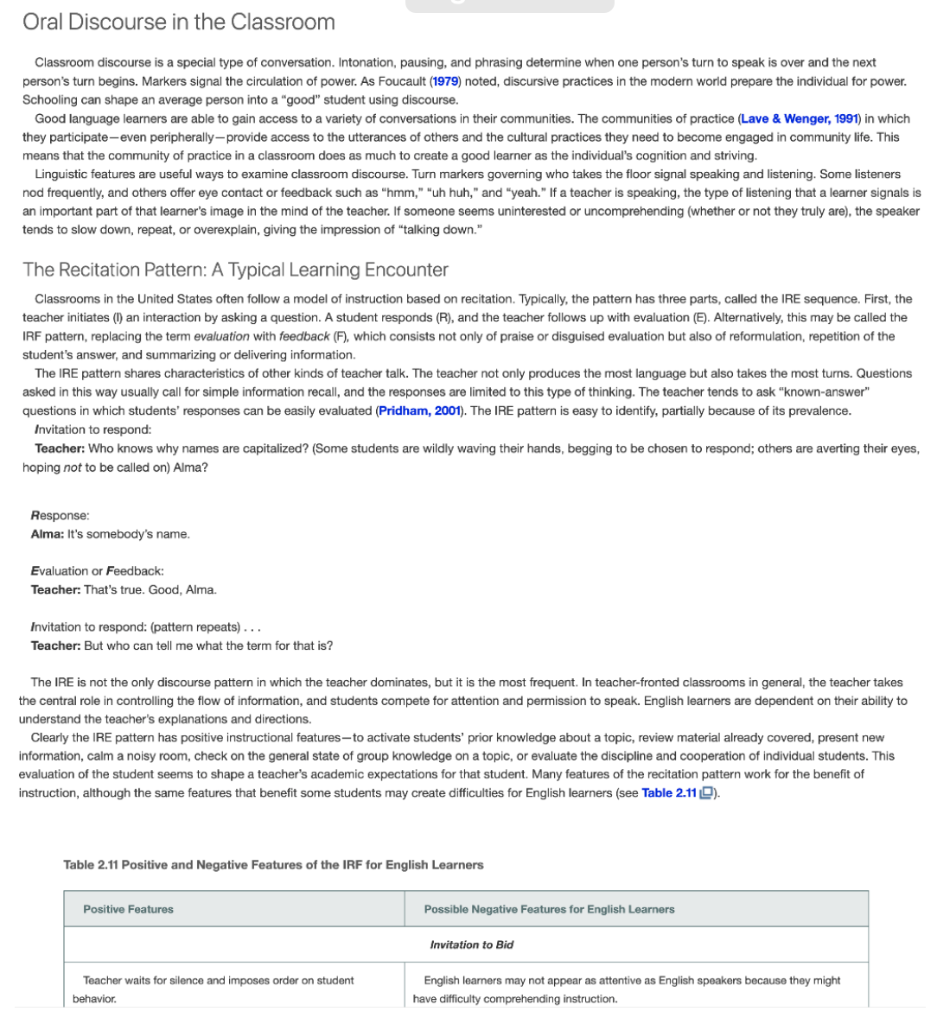

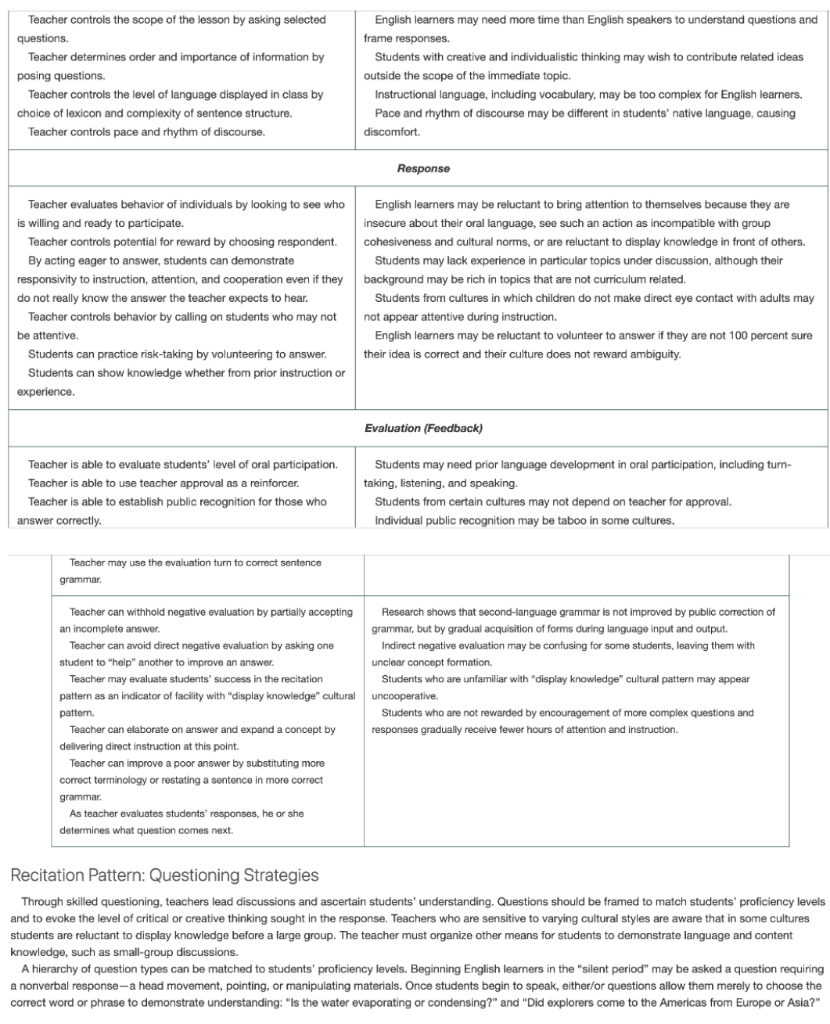

2 Language Structure and Use Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able to ... Explain how language contributes to human life; List the universal features of language; Identify key aspects of phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics; Give examples of language functions and features of academic discourse; Describe how pragmatics influences verbal language; and Survey the ways that dialects and language variation affect English learners. Human Language Verbal language is highly developed in human beings. It allows us to express our deepest feelings, our broadest concepts, and our highest ideals. It takes us beyond the here and now, and even beyond the possible-by means of language, we might join the attackers at the siege of Troy or journey through the looking glass with Alice. Language can connect humans as children listen to stories before the fireplace on a cold winter night; or it can, together with culture, divide two peoples into bitter sectarian warfare. Language communicates the heights of joy and the depths of despair. As teachers, we share the responsibility with parents and other caregivers to increase the language skills of our students. There can be no effort more noble or worthwhile. Linguistics Helps Teachers to Understand English Learners Understanding language structure and use provides teachers with essential tools to help students learn. All languages share universal features, such as the ability to label objects and to describe actions and events. All languages are divided into various subsystems (phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics). What is most amazing is that language users learn I these subsystems of their first language without realizing it-native speakers are not necessarily able to explain a sound pattern, a grammatical point, or the use of idiomatic expression. To them, that is "just the way i s." Language, then, a system that works even without conscious awareness, an inborn competence that unfolds and matures when given adequate stimulation from others. Education about language can help students to sharpen their linguistic knowledge about their first language as they acquire skills in their second language(s). This chapter explores the various aspects of language and provides suggestions to help English-language development (ELD) teachers identify student needs and provide appropriate instruction. Knowledge about language structure and use also helps teachers recognize the richness and variety of students' skills in both first and second languages. Linguistic knowledge- not only about English but also about the possibilities inherent in other languages-helps teachers view the language world of the English learner with insight and empathy. Language Creates Both Equality and Inequality Language equalizes-most preschoolers (those without language difficulties) as well as professors are native speakers of their first language. By the age of five, most children have learned how to make well-formed sentences in their native language and, although they do not have as extensive a vocabulary as they will later in life, can be considered native speakers. Although some students may be shy or their language skills delayed in development, it is incorrect to say that a young child "doesn't have language." Every healthy child-regardless of racial, geographical, social, or economic heritage-is capable of learning any language to which he or she is exposed. Alternatively, language may reflect inequality-dialect distinctions often demarcate social class. One group of speakers of a language may look down upon others. whose dialect differs, and speakers of a dominant language may discriminate against those who speak a minority language. One goal for teachers is sustain equality of language: to respect the language that students bring to class, and to regard students as language experts, full participants in the linguistic world that surrounds them. Whether this participation takes place in the primary or secondary language, each human has access to the linguistic resources that create and sustain culture and give meaning to life. The role of the teacher is to develop these resources. Language Universals At last count, 7,099 languages are spoken in today's world (SIL International, 2017). If that seems to be an increase over the figure 6,912 of the year 2000, it may be because the definition of what constitutes a distinct language may have changed. Although not all of these have been intensely studied, linguists have carried out enough investigations over the centuries to posit some universal facts about language. All Languages Have Structure All human languages use a finite set of sounds (or gestures) that are combined to form meaningful elements or words, which themselves form an infinite set of possible sentences. Every spoken language also divides these discrete sound segments-phonemes-such as /t/, /m/, or /e/ into a class of vowels and class of consonants. All grammars contain rules for the formation of words, and sentences of definite types, kind, and similar grammatical categories (for example, nouns and verbs) are found in all languages. Every language has a way of referring to past time; the ability to negate; and ways to form questions, issue commands, and so on. Although human languages are specific to their places of use and origin (for example, languages of seafaring cultures have more specific words for oceanic phenomena than do languages of desert tribes), semantic universals, such as "male" or "female," are found in every language in the world. No matter how exotic a language may appear to a native-English speaker, all human languages in fact share the same features, most of which are lacking in the language of apes, dolphins, or birds. Language Is Dynamic Languages change over time. Pronunciation (phonology) changes-across 400 years, for example, Shakespeare's plays often feature scene-ending couplets whose words may have rhymed in his day but do not in the modern day. We recognize that pronunciation in English has altered over time, because the spelling of some words is archaic: We no longer pronounce the /k/ in knight or the /w/ in write. Semantics change over time, and words disappear, such as the archaic English words bilbo, costermonger, and fluey. Words expand their meanings, as with geek and mouse. New words appear, such as nannycam and freeware. Some languages change more than others: Written Icelandic has changed relatively little since the thirteenth century, whereas writers for Wired, a New York-based technology magazine, coin an average of twenty-five new words in English with each month's edition (examples: robopocalypse, Russianly, Googleable, upside- downier, infoporn). Teachers who respect the dynamic nature of language can take delight in learners' approximations of English. When Chinese speakers fail to produce past-tense markers ("Yesterday I download a file) (asterisks in this chapter indicate sentences that are ungrammatical or have incorrect words), they may be speaking the English of the future, when the past-tense morpheme (-d, -ed, -t) may have been dropped, just as the second-person inflection (-est, as in "thou goest") has disappeared. In spoken English, "whom" is gradually disappearing, and "less" is gradually taking the place of "fewer" when speaking of countable nouns (as in "less opportunities"). In the Los Angeles regional dialect, many people use a variant form of the past participle for certain verbs, which in the past would have been frowned upon: **shouldn't have went" and *"should have came." These changes demonstrate the ways that languages change over time. Language Is Complex Without question, using language is one of the most complex of human activities, providing the human race with a psychological tool unmatched in power and flexibility. It is normal for humans no matter their native language to be able to communicate a wide range of concepts, both concrete and abstract. All languages are equally complex, capable of expressing a wide range ideas and expandable to include new words for new concepts. Motu, one of 715 indigenous languages in Papua New Guinea, has a complex vocabulary for indigenous plants, whereas Icelandic has an elaborate system of kinship names that allows people to trace their ancestry for hundreds of years. Not only is vocabulary rich and detailed, but syntax, phonology, and pragmatics are also complex features of the many languages across the globe. Language is arbitrary, meaning that we cannot guess the meaning of a word from its sound (except for a few words such as buzz). There is no inherent reason to link the sound and meaning of a word. Because the meaning-symbol connection is arbitrary, language gains an abstracting power removed from direct ties to the here and now of objects r events. Moreover, language is open-ended-an infinite set of sentences can be produced in any language. Even though language is complicated, almost all aspects of a person's life are touched by language. Although language is universal, each language has evolved to meet the experiences, needs, and desires of a particular community. Did You Know? The Korean Language Korean is the only language to have true alphabet completely native to East Asia, with each character corresponding to a phoneme (ten vowels, nineteen consonants, and vowel-like consonants called glides). Korean has no articles, word gender, or declensions. There are no adjectives; instead, verbs can be used as adjectives. There are also extensive variations of verb forms used o indicate tenses and honorifics. The Building Blocks of Language Phonology: Phonemes, Phonemic Sequences, and Phonemic Awareness Phonology is the study of the sound patterns of language. Phonetics concerns the production of speech sounds by humans of the production, reception, analysis, transcription, and classification of speech sounds, and also, "the relation of speech sounds to the total language process" (Heilman, 2002, p. 4). Did You Know? Is It English? These activities illustrate the characteristics of the English sound system: Phonemes The individual sounds in a language, the distinctive units that "make a difference" when sounds distinguish words, are phonemes. For example, in English the initial consonant sounds /p/ and /b/ are the only difference between the words park and bark and thus are phonemes. The number of phonemes in a language ranges between twenty and fifty: English has a high average count, from thirty-four to forty-five, depending on the dialect. Hawai'ian, in contrast, has one of the lowest phoneme counts, with eight consonants and ten vowels. Table 2.1 lists the phonemes in English (using the International Phonetic Alphabet) with example words. Vowels Table 2.1 Phonemes in English: Vowels and Consonants /A/ /a/ /E/ /e/ /V N /0/ /0/ /U/ /u/ Which of the following are possible English words and which would be impossible because they do not fit the English sound system? stgmonic, chetelogo, ndele, tassitic /00/ (Answer: not stgmonic and ndele-they contain non-English-like consonant clusters) Products are often brought to the market with names that use phonemic enhancement: The gasoline company and product Esso was renamed Exxon in 1973 in part because test marketing showed that people responded more strongly to the look and sound of the double X than the double S. /00/ Examples wake, pain, tray pat be, beat, flee set I, tie, by if, tin no, moat, stone pot futile, Tuesday cup, dumb to, rue, chew, boot soot, put Consonants /b/ /k/ /d/ /4/ /g/ /h/ N N /m/ / /p/ /kw/ Examples bet, habit, rub cake, naked, lack do, sadder, wed far, offer, half, phony gone, digger, beg head, behold jam, tragic, stage, ledge light, willow, well mine, dim none, fun, Lynne push, topple, step quiet /oi/ /ou/ /aw/ /ar/ toil, boy pout, how, mouse saw, call, caught far / /s/ Not in Japanese: /dg/ // // /th/ /oo/ /v/ /schwa/ Not in Spanish: /dg/ // /sh/ /th/ /z/ IN /v/ /w/ /ks/ or /gz/ lyl /2/ /sh/ /hw/ /ch/ /th/ /th/ or a g/ /zh/ rope, Larry, bar sip, hustle, miss tip, after, bat vet, hover, gave wag, away sox, exit your, yet zip, noisy, buzz shout, lotion, wash what chop, pitch thing, southside, north that, mother, soothe wing, running genre, collision, pleasure If phonemic variations do not distinguish words, they are considered variations of one phoneme rather than completely different phonemes. For example, in English at least in the Pittsburgh dialect-the name "Lynne" is pronounced with the tongue to the back of the roof of the mouth, whereas when pronouncing the name "Linda" the tongue is tipped farther forward. However, both are acceptable versions of the // phoneme because this difference alone does not distinguish two word meanings, as does the difference between pan and ban. English learners' aural comprehension and pronunciation may be affected when English words contain phonemes that are unfamiliar to them. The schwa (the sound of the "e" in the phrase "the hat") is often difficult for Spanish speakers because Spanish vowels rarely alter their sound quality in unaccented syllables. A digraph-a pair of letters used to write one sound or a combination of sounds that does not correspond to the written letters combined-may confuse the English learner who attempts to separate the digraph into two separate phonemes. The concept of diphthong (defined as a vowel blend with two adjacent vowels, each of which is sounded) may transfer in principle from another language, although the diphthongs may differ from language to language. Mandarin has diphthongs (shyueh), as does Spanish (hay). Did You Know? English Phonemes Not Found in Other Languages Some phonemes in English do not exist in certain other languages. English learners from these backgrounds might experience difficulty in hearing and producing these sounds. Phonemic Sequences Each language features permissible ways in which phonemes can be combined in a language (for example, English has many words with three-consonant clusters such as /str/ and /scr/, whereas Mandarin does not). Languages also have permissible places for these sequences: initial (at the beginning of a word), medial (between initial and final position), and final (at the end of a word), or in a combination of these positions. In English, /spr/ as in spring, d/ as in handle, and /kt/ as in talked are permissible phonemic sequences, but neither d/ nor/kt/ can be used initially ("ndaft is not permissible). English allows /sp/ in all three positions-speak, respect, grasp-but restricts/pt/ to only one-apt (the word optic splits the phonemes into two syllables; the word pterodactyl has a silent p). Phonemes can be described in terms of their characteristic point of articulation (tip, front, or back of the tongue), the manner of articulation (the way the airstream is obstructed), and whether the vocal cords vibrate or not (voiced versus voiceless sounds). Not all languages distinguish between voiced and voiceless sounds. Arabic speakers may say "barking lot" instead of "parking lot" because to them /p/ and /b/ are not distinguishable. Phonemic Awareness As children learn language, they acquire phonological awareness in the process of separating the oral sound stream they encounter into syllables and words. Literacy development builds on this ability, helping young readers connect sounds to written symbols. Phonemic awareness is the ability to use the sound-symbol connection to separate sentences into words and words into syllables in order to hear, identify, and manipulate the individual phonemes within spoken words. This is not an easy task, with ten to twenty phonemes articulated per second in normal speech. Phonemic awareness tasks help students hear and isolate individual phonemes. This is the basis of phonics instruction (see Chapter 7). Phonology: Stress, Pitch, Rhythm, and Intonation Stress Besides phonemes, characteristics of language sounds include stress, pitch/tone, and intonation. Stress, the amount of volume a speaker gives to a particular sound, operates at two levels: word and sentence. Stress is a property of syllables-stressed syllables are longer and louder than unstressed syllables. Within words, specific syllables are stressed. In some languages, stress is predictable; in Czech, stress is usually on the first syllable of a word; in French, on the last syllable of a phrase. Stress is difficult to learn in English because there are "no consistent rules" (Dale & Poms, 2005, p. 84). Incorrect stress can alter the meanings of words. the following examples, the stressed syllable is indicated by the accent mark': dsert dessert invalid invlid noun, "dry region" noun, "sweet foods after the main meal" noun, as in "person with long-term, debilitating illness" adjective, as in "null, void" (Dale & Poms, 2005, p. 84) Stress can further be used at the sentence level to vary emphasis. For example, the following sentences all carry different emphases, and thus different words are stressed: Kimberly walked home. (It was Kimberly who walked home.) Kimberly walked home. (She walked; she did not ride.) She walked home. (She walked home, not to Grandma's house.) In some cases, the wrong stress on a word completely undermines comprehension. Students who learn a second language sometimes have difficulty altering the sounds of words in the context of whole sentences. Thus, teachers are better served by teaching words in context rather than in lists. Classroom Glimpse A Misplaced Word Stress C Rashid sat down, shoulders slumped. "I'm beginning to get discouraged. People don't understand my speaking." "Give me an example," I suggested. Rashid continued, "At lunch my friend was eating something mashed. I said 'That looks like potty toe.' She gave me a strange look." "Potty toe?" I asked. "What in the world do you mean? You'd better write down the word." (He wrote the word.) "Oh!" I exclaimed, looking at the paper. "Potato!" Pitch and Prosody Other sound qualities are important in oral speech. Pitch at the word or sentence level is a phonological component of language that plays a key role in determining meaning. "Eva is going," as a statement, is said with a rise on the syllable "go," followed by "-ing" with a falling pitch; but said as a question, the pitch rises at the end. Tone languages use the pitch of individual syllables to contrast meanings (examples are Thai, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Zulu, Apache, Navajo, and Kiowa). Pitch interacts with word stress to produce prosody, the underlying rhythm of the language. The way an individual word fits into a sentence may change the stress. For example, in the sentence "He's my uncle-Uncle Bob," the first use of "uncle" is heavily stressed on the first syllable because the syllable is placed in the first clause at the climax of the prosodic contour, just before the final pitch drop. During the second "uncle," neither syllable is stressed, because the name "Bob" carries the emphasis, hence the stress. Because English words are pronounced with different stress depending on their locations in sentences, in contrast to Spanish, in which the vowels are more apt to maintain their sound values irrespective of placement, Spanish speakers may have difficulty achieving the prosody of the native speaker of English. Typical problems in English prosody include the tendency to pronounce all words with equal emphasis, avoiding contractions (thus sounding stilted), and pausing incorrectly between words. To achieve proper prosody, words in phrases are blended together and functional words are reduced in emphasis ("How are you" sounds like "Howaru?"), and sounds are linked across words, so that "We've eaten" sounds like "We veaten." Smooth prosody is a combination of phrasing and pausing: "Please//do your chores//before you go out." Intonation Patterns The use of pitch to modify sentence meaning is called intonation. Each language has a distinctive sound flow across the sentence. The English pattern is characterized by accented and unaccented syllables, the same patterns found in English poetry. The lamb is a beat with one unaccented syllable followed by an accented one, as in the phrase "too late to go." An anapest is a beat with two unaccented syllables followed by an accented one: "in the heat of the night." Most sentences in English combine accented and unaccented syllables in an undulating rhythm until just before the end of the sentence, at which time the pitch rises and then drops briefly. In contrast, Cantonese, as a tonal language, has intonation variation that distinguishes words by tone, but an entire sentence does not have a rise-and-fall curve. Because English, for example, makes use of a questioning intonation to soften the demanding nature of a request ("Could you sit down over there?"), a Cantonese speaker may sound brusque to English ears ("Could! You! Go! Sit! Down! Over! There!"). Intonation matters a great deal when language fulfills social functions. Contrastive analysis-paying careful attention to phonemic differences between languages and then spending more time teaching those phonemes that differ- has been found to be relatively nonproductive as a teaching methodology. There is little evidence that learners will find general phonemic differences between languages to be difficult. Error analysis, however, can guide teachers; making careful note of a learner's difficulties can provide evidence about the need for specific interventions. Empirical teaching-teaching guided by data-helps to focus phonological training directly on the learner's difficulties. Guidelines for teaching pronunciation are featured in Chapter 6. Morphology: The Words of Language Morphology is the study of the meaning units in a language. In some cases in English, individual words constitute these basic meaning units (e.g., chase). However, many words can be broken down into smaller segments-morphemes-that still retain meaning. Morphemes The basic building blocks of meaning are morphemes, small units that cannot be further subdivided. Fundamentalists is an English word composed of five morphemes: funda + ment +al + ist + s (root + noun-forming suffix + adjective-forming suffix + noun-forming suffix + plural marker). Morphemes can be represented by a single sound, such as /a/ (a stand-alone, r free morpheme meaning an indefinite article as in a girl) or /a-/ (a bound morpheme meaning "without," as in amoral or asexual). Morphemes can be a single syllable, such as the noun-forming suffix -ment in amendment, or two or more syllables, such as in lion or parsley. As we have seen, morphemes may have the same sound with two different meanings, such as the -er in dancer ("one who dances") and the -er in fancier (the comparative form of fancy). A morpheme may also have alternate phonetic forms: The regular plural -s can be pronounced either /z/ (bags), /s/ (cats), or /iz/ (bushes). Morphemes are of different types and serve different purposes. Free morphemes can stand alone (envelope, the, through), whereas bound morphemes occur only in conjunction with others (-ing, dis-, -ceive), either as affixes or as bound roots. Affixes at the beginnings of words are prefixes (un- in the word unafraid); those added at the ends are suffixes (-able in the word believable); and infixes are morphemes inserted between other morphemes (-s-in mothers-in-law). Part of the power and flexibility of English is the ease with which longer English words are formed by adding prefixes and suffixes to root words (cycle, cyclist; fix, fixation). The predictability of meaning carried by standard affixes can make it easier for students to learn to infer words from context rather than relying on rote memorization. Best Practice Morphemes To generate interest in science concepts, at the beginning of each general science unit Mrs. Silvestri selected several roots from a general list (astro, bio, geo, hydr, luna, photo, phys, terr). She then asked students to work in pairs to search their texts for words with those roots from the relevant chapter in the science text. Next she handed out a list of prefixes and affixes and asked each pair to generate five to ten English words that are new to them, including definitions. Students wrote each new word and its definition on two index cards and played a memory matching game with their card decks. Word-Formation Processes English has historically been a language that has grown in vocabulary either by borrowing extensively from other languages or by coining new words from extant terms. Studying how new words are formed-largely from existing morphemes-helps English learners understand morphemes. Clipping is a process of shortening words, such as prof for professor or the slangy teach for teacher. If students learn both the original and the clipped versions, they gain the sense that they are mastering both colloquial and academic speech. In English, acronyms are plentiful, and many are already familiar to students-USA, CNN, and NASA, for example. A list of acronyms helps students increase their vocabulary of both the words forming the acronyms and the acronyms themselves. Who can resist knowing that laser is light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation? Words formed from parts of two words are called blends-for example, chortle from chuckle+ snort and travelogue from travel + monologue. Students can become word detectives and discover new blends (Spanglish, jazzercise, rockumentary) or create their own blends (a hot dog in a hamburger bun can be a hotburger). Using Morphemes in Teaching Students can add to their enjoyment of learning English by finding new words and creating their own. Those who play video games can make up new names for characters using morphemes that evoke pieces of meaning. Advertising copywriters and magazine writers do this on a daily basis; the word blog is a combination of the free morphemes web and log; then came vlog (video /v/ from "video" added to log). The prefixes e- and i- have combined to form many new words and concepts over recent decades (e.g., e-pets and iTunes). The study of morphology is fun and increases word power. Depending on the student's first language, some morphemes are easier to acquire than others. For example, the prefix en-, meaning "to bring about, to make, or to put into," is more often used to make verbs from nouns or adjectives that derive from the Anglo-Saxon side of English-that is, words not directly related to cognates in Romance languages. For example, one can say "enjoy" but not "enmuse." In contrast, words ending in the noun suffix-ion are relatively easy for Spanish speakers because they are usually words that have cognates in Spanish. Therefore, students may not as easily acquire the words in Table 2.2 as they might those in Table 2.3. Table 2.2 Words with Morpheme en- as Prefix enjoy enlarge enrich entrap enable enact enclose encourage entangle encrust enliven ensure entrust enroll enforce Table 2.3 Words with Morpheme -ion as Suffix transportation action examination preparation certification division succession combination signification termination translation comparison validation respiration separation Attention to morphemes in the classroom can accelerate language acquisition if students are exposed to families of words across parts of speech-that is, if courage is taught alongside courageous, discourage, and encourage or ice is taught with icy, ice cream, icicle, ice age, and iceberg. Instead of defining new words, students may enjoy separating new words into morphemes and finding other words that match these morphemes. This activity is consonant with a key principle of brain-based learning (Chapter 3): The brain learns faster when engaged in pattern-matching or pattern-finding activities. Best Practice Working with Morphemes The teacher can encourage awareness of comparatives and superlatives using the following game, called Speed Search. Students circulate around the room to see how many people they can find who fit the description on the slip of paper they have drawn from box. After two minutes, they draw another slip for a second round of play. Students win if they have the most points after a designated number of rounds. Sample descriptions: Find a person who believes that dogs are less intelligent than cats. Find a person who has more than two brothers. Find a person who is the oldest child in the family. (Kealey & Inness, 1997, pp. 24-25) Syntax: The Sentence Patterns of Language Syntax refers to the rules that govern the formation of phrases and sentences. The words in a language have semantic properties that entail their use in sentences in some ways and not in others. A well-formed sentence is more than the sum of the meanings of the words; in English the position of the word in a sentence is an important part of the overall meaning. Sentence A, "The teacher asked the students to sit down," has the same words as sentence B, "The students asked the teacher to sit down," but not the same meaning. Not every sequence of words is a sentence: Sentence C, "*Asked the the teacher to down students sit," violates syntactic rules in English and thus has no meaning. Native speakers of a language have syntactic proficiency-they can distinguish syntactically correct from incorrect combinations of words, even though they may not be able to explain what syntactic rules have been violated. Even very young English-speaking children know that sentences A and B are meaningful but sentence C is not. Moreover, the mind is a strong organizing force, constantly striving to gain meaning, so speakers of a language can comprehend even imperfectly formed sentences. Whereas syntax refers to the internally constructed rules that make sentences, grammar looks at whether a sentence conforms to some standard. An important distinction, therefore, is the one between standard and colloquial use. Many colloquial usages feature acceptable sentence patterns in English, even though their usage is not standard-for example, "I ain't got a pen" is acceptable English syntax but not standard usage. Teachers who are promoting the standard dialect need to be aware that students' developing competence will not always conform to that standard. Besides grammaticality and word order, speakers' syntactic knowledge helps them understand three other sentence features. Double meaning, or ambiguity, occurs in sentences such as "She is a Korean karate expert" or the frequently seen "Please wait for the hostess to be seated." On the other hand, sentences can have different structures but mean the same thing: "He is hard to please." "Pleasing him is hard." and "It is hard to please him." Finally, speakers can understand and produce novel utterances, the creative aspect of language. Explicit Teaching of Syntax In the late twentieth century, it was widely believed that students could acquire a second language without explicit teaching of syntactic structures. However, because the mind seeks to acquire patterns, and syntax is a pattern, it is now thought that creative and systematic teaching of syntax can accelerate language learning. Grammar books that teach students to label the parts of speech and build up sentence structures from simple to complex are useful. Balancing this systematic instruction with grammar games and creative language engagement such as poetry-or even Mad Libs, the game that has students blindly providing nouns, adjectives, and verbs without knowing the story plot-helps students to learn the parts of speech. Teachers often use a hanging card "pocket chart" holder to teach sentence syntax. Students can work in pairs to assemble meaningful sentences using packs of sentence components. Words in the same sentence should be on the same color of index card so that multiple sentences can be kept separated as students work. A trick to checking students' work quickly is for each set of cards to spell out a word on the back of the cards if the cards are in the correct order. Some students have more metalinguistic knowledge than others-that is, they have the vocabulary to talk about grammar because they learned the grammar of their native language. As with other kinds of learning, the wise teacher assesses students' prior knowledge to learn where to begin instruction. Describing the characteristic differences between languages-contrastive analysis-is useful to some degree in predicting what kinds of syntax errors students make (see Box 2.1 for Mandarin and Box 2.2 for Spanish). However, direct instruction must also be balanced with rich, authentic exposure to English sentences, both spoken and written, and the learner must be allowed time for syntactic structures to be absorbed, consolidated, and deployed many situations before a given structure can be said to be a stable feature of the learner's repertoire. Box 2.1 English Syntax Contrasted with Chinese (Mandarin) English learners with Chinese as a mother tongue may need additional teacher assistance with the following aspects of English: Verb tense: "Yesterday I see him. In Chinese, the verb form is not changed to mark the time during which the action occurred-the adverb, not the verb, signals the time. Conjugating the verb form in English may prove to be difficult for the learner. Subject-verb agreement: "He see me. In Chinese, verbs do not change form to create subject-verb agreement. Word order: "I at home ate. In Chinese, prepositional phrases usually come before the verb-the rules governing adverb placement in English are difficult for many learners. Plurals: *They give me 3 dollar. In Chinese, like English, the marker indicates number, but the noun form does not change to indicate plural; in English the noun form changes. Articles: *No one knows correct time. Chinese uses demonstrative pronouns [this one, that one] but not definite or indefinite articles [a, the]. The rules for such use in English are complex. Box 2.2 English Syntax Contrasted with Spanish English learners with Spanish as a mother tongue may need additional teacher assistance with the following aspects of English: Verb conjugation: Spanish has three groups of regular verbs, in contrast to one group in English (those that add -ed or -d), but English has more classes of irregular verbs (wildly irregular go/went/gone versus mildly irregular like send/sent, break/broke, etc.). Subject-verb agreement: In Spanish, first-, second-, and third-person forms must be changed from the base form to create subject-verb agreement. It is sometimes hard to remember that in English only the third-person form is changed. Noun/adjective order: In Spanish, adjectives come sometimes before and sometimes after the noun (un buen da, un da linda). These alterations, however, obey regular rules. Articles: Spanish, like English, uses both definite and indefinite articles, but with different rules (for example, languages need the definite article, el ingles). Both definite and indefinite articles must match the noun to which they refer (unos muchachos, las mujeres). Source: Spinell (1994) Semantics: The Meanings of Language Semantics is the study of the meanings of individual words and of larger units such as phrases and sentences. Speakers of a language learn the "agreed-on" meanings of words and phrases in their language; these meanings must be shared, or communication becomes impossible. However, English is a flexible language that is responsive to the needs of a dynamic culture, and new concepts emerge daily that require new words; English learners must acquire vocabulary continuously to keep up with semantic demands. Some words carry a high degree of stability and conformity in the ways they are used (slap as a verb, for example, must involve the hand or some other flat object-"He slapped me with his ball" is not semantically meaningful). Other words carry multiple meanings (e.g., scrap), ambiguous meanings (bank, as in "They're at the bank"), or debatable meanings (marriage, for example, for many people can refer only to heterosexual alliances, whereas others might apply it to nonheterosexual contexts). Semantic Challenges in English In second-language acquisition, there are three basic semantic challenges. First is the process of translating-finding words (lexical items) in the second language that correspond to those already known in the first. The second challenge is learning words for ideas and concepts that are new in the second language for which there is no first-language counterpart (for example, the Polish term fcha-"to use company time and resources to one's private ends"-has no equivalent in English) (de Boinod, 2006). The third challenge involves similar words that are in both languages whose meanings differ in small or large ways. Table 2.4 lists words that are cognates in English and Spanish-their meaning is identical. Table 2.5 lists near cognates, and Table 2.6 lists false cognates-those in which the similar appearance is misleading. Table 2.4 Examples of English-Spanish Cognates English March April May June July August (Same meaning, same spelling; may be pronounced differently) button club February much director office hotel hospital mineral Table 2.5 Examples of English-Spanish Near Cognates postal (Same meaning, slightly different spelling; may be pronounced differently) perfume courtesy Spanish febrero marzo abril mayo junio julio agosto botn mucho plural oficina radio cortesa rural salmon (Spanish salmn) sofa (Spanish sof) tenor violin (Spanish violn) English tranquil salt violet second intelligent problem cream check (bank) deodorant garden map Spanish tranquilo sal violeta segundo inteligente problema crema cheque desodorante jardin mapa lamp medal Table 2.6 Examples of English-Spanish False Cognates Spanish (Close in sound; slightly different spelling; different meaning) blando blanco campo codo despertador direccin cola plata soft Meaning in Spanish white country elbow alarm clock lmpara address medalla tail silver bland English False Cognate blank camp code desperate direction cola paper plate use papel uso Meaning in English soothing; not stimulating or irritating colorless; free of writing place for tents or temporary shelter a system of signals almost beyond hope drink the way to go; authoritative instruction sheet of metal, food dish Another challenge in English is the extraordinary wealth of synonyms. One estimate of English vocabulary places the number at more than million words; the Oxford English Dictionary contains about 290,000 entries with some 616,500 word forms (Oxford English Living Dictionaries, 2017). Fortunately, only about 200,000 words are in common use, and an educated person draws from a stock of about 20,000 to use about 2,000 in a week (SIL International, 2017). The challenge when learning this vast vocabulary is to distinguish denotations, connotations, and other shades of meaning. Best Practice Nuances of Meaning For adolescent learners, the teacher provides a list of a dozen common emotions (love, anger, fear, and fright are the big four; a few others are thankfulness, doubt, guilt, surprise, contempt, delight, hunger, nervousness). Students, working in pairs, make up situations that would engender the emotion. Rich discussion about nuances of meaning might result! Acquiring Vocabulary Word Knowledge What does it mean to "know" a word? Recognizing a word involves matching stored meaning with meaning derived from context. In addition, knowing a word includes the ability to pronounce the word correctly, to use it grammatically in a sentence, and to know with which morphemes it is appropriately connected. This knowledge is acquired as the brain absorbs and interacts with the meaning in context, possibly due to the important role that context plays in forming episodic memory-memory that is tied to emotionally rich experience. Nation (1990) lists the following as the types of word knowledge necessary for complete comprehension of a given word: its spoken form, written form, grammatical behavior, collocational behavior (what words are frequently found next to the word), frequency, stylistic register constraints (such as formal/informal contexts), conceptual meaning, and word associations (such as connotations). In contrast, Scrivener (2005) posits thirty-two dimensions of a lexical item; he includes such features as homonyms and homophones, personal feelings about a word, appropriacy for certain social situations and contexts, and visual images that people typically have for the word. This makes "knowing" a word even more complicated! Vocabulary knowledge can be passive, controlled active, or free active (Laufer & Paribakht, 1998). Passive knowledge involves understanding the most frequent meaning of a word (e.g., break-He breaks a pencil). Controlled active knowledge can be described as cued recall (e.g., The railway con the city with its suburbs), and free active knowledge describes the ability to spontaneously use words. Each type of knowledge develops at a different rate, with passive understanding growing faster than active word use. Passive vocabulary is always larger than active vocabulary. Many methods have been used to teach vocabulary during second-language acquisition; rote memorization of lists or flash cards with words and meanings can be very effective, especially when picture cues are provided. Rich experience of new words in the context of their use is the way words are usually acquired in the first language. Games such as Pictionary and Total Physical Response are useful when objects and actions are simple. More nuanced or complex knowledge requires careful work at all the levels described earlier by Nation (1990). Academic Vocabulary Acquiring the vocabulary used to educate is essential to school success; it is a large part of what Cummins (1979) called cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP). This vocabulary has been compiled by various researchers (see, for example, Bromberg, Liebb, & Traiger, 2005; Huntley, 2006). Although no exhaustive list exists of academic terms by grade level, Table 2.7 presents academic terms by approximate grade level. Table 2.8 displays examples of academic vocabulary. period Table 2.7 Examples of Cognitive Academic Words by Approximate Grade Level grade mistake chalk file capital letter access adjust alter Grade 1 connect check aspect ruler approach label Grade 2 draft measure dictionary chart width schedule Table 2.8 Examples of Academic Vocabulary Source: From Huntley (2008). margin margin available capacity clarify comment complex Grade 3 indent proofread paragraph hyphen topic graph edit ignore select component confirm consistent contrast core Grade 4 define method highlight environment exhibit layer region research style element emphasis instance random specific Grade 5 summarize evidence energy positive gender nuclear source substitute theme Grade 6 survey minimum initial sufficient visible estimate undergo factor percent simulate transfer supplement variable volume Best Practice Key Principles for Teaching Vocabulary Teach vocabulary with collocations-words that co-appear commonly (for example, the verb lose is presented as "lose your way," "lose your temper," "lose your keys," etc.) Teach vocabulary within its grammatical environment (for example, verbs are always introduced with to-"to apply," "to return") Emphasize register (teach where, when, with whom a word is used; in a formal or informal setting?) Emphasize word form (does it include a prefix or suffix as a clue toward meaning?) Emphasize connotation (nuances of meaning differentiating one word from another) Source: Dalolu (2005). Semantic Shifts Language users must become aware of the semantic requirements when writing. It may be understandable when a speaker overuses the colloquial "you know" when telling a story, but in written English, one must shift toward more formal expression. Learning to make this shift is an important part of cognitive academic language proficiency. Only in certain types of writing-such as literature when a colloquial dialect is expressed, or in gonzo journalism, a flamboyant, first-person genre is the colloquial form acceptable. Teachers can emphasize this semantic shift by, for example, using a chart that compares "talk written down" with "more thoughtful writing." Table 2.9 contrasts these two writing styles as semantic shifts. Table 2.9 Semantic Shifts When Writing Informal Register you know a lot of, a whole bunch of getting (dark, warm) a piece of to take a chance to make an offer to on oing Formal Register it is evident multiple becoming a component of to attempt to offer to continue Semantics is a domain in which growth must be sustained at every level of schooling and in every content domain. Teacher education, for example, has its own lexicon; prospective teachers are asked to master such terms as assertive discipline, wait-time, manipulatives, mind mapping, retelling, writing genre, mini-lesson, and so forth. Demonstrating proficiency in these and similar terms is measure of professionalism. Language Functions and Academic Discourse Language proficiency is not an end in itself; language is used for various purposes-to solve problems, communicate feelings, or keep records as people go about their daily routines. Halliday (1978) has distinguished seven different functions for language: instrumental (getting needs met), regulatory (controlling others' behavior), informative (communicating information), interactional (establishing and maintaining social relationships), personal (expressing individuality), heuristic (investigating and acquiring knowledge), and imaginative (expressing fantasy or possibility). In every situation, participants are expected to use language to carry out specific routines. One of the important tasks of kindergarten and first-grade teachers is to teach children how to respond appropriately in the school setting. As students acquire a second language-English-they are exposed to a distinct set of language functions that are specially adapted for school. Language functions used in schools are not necessarily academic; many are regulatory (maintaining order, for example), instrumental (setting up activities), and interpersonal (carrying out social relations). Confusion and a sense of alienation can arise for English learners who are used to the school routines in their own countries and face the unexpected in U.S. schools. A knowledgeable teacher recognizes that these students are acting according to the routines with which they are familiar. It may take time-and explicit language coaching for students to learn the language functions appropriate for a U.S. school context. In school, language is used differently than in the experiences of everyday life. This can work to the benefit of English learners if educators can affirm the voices that students bring to school and encourage them to build the second language on the knowledge they have gained in their first language, thus increasing their academic potential. Academic Language Functions across a Academic language functions include explaining, informing, justifying, comparing, describing, proving, debating, and so forth. There is some overlap in the terminology of acad ons and of thinking skil Academic English-also called designed r abstract, decontextualized performa variety of content domains, which requires a long period of successful schooling; exposure to academic language, feedback, and support in its use by students; and explicit instruction in vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and cognitive strategies (see Chapter 5). Table 2.10 aligns academic language functions with typical phrases that are used during that function. Table 2.10 Phrases Associated with Academic Functions of Language Function of Language indicating cause and effect providing example comparing emphasizing indicating sequence summarizing Sample Phrase(s) therefore, as a result, gradually for instance, that is, one sample, such as, in fact like, likewise, similarly, in much the same way, equally moreover, chiefly, above all in the first place, starting with, consequently, finally to conclude, in other words, thus Academic language often includes such functions as reporting, evaluating, questioning, and critiquing. Many other functions are not necessarily encouraged by schools but take place nonetheless: interrupting, shifting the blame, threatening, accusing, arguing, demanding, and making excuses. Learners must begin to understand how language functions to acquire written as well as spoken competence in the effort to match forms with functions. Providing English learners with opportunities to engage in the various functions of language is critical for enabling them to develop a full range of proficiency in English. In school, however, rarely do teachers allow students to practice "out of school" social functions; the emphasis is usually on language functions necessary for the work of learning. Best Practice Acquiring Language Functions . . . Instrumental: Students practice a list of ways to request actions of others, including "Could you..." "Would you mind.... Regulatory: Students take turns acting as timekeeper and taskmaster in cooperative groups. Informative: Students keep records of classroom pets, weather patterns, or commonly misspelled words on a bulletin board. Interactional: Students work together to plan field trips, social events, and classroom and school projects. Personal: Students use personal language in a journal and then share their thoughts and opinions on a voluntary basis. Heuristic: During projects, students brainstorm questions about which no one knows the answer. Imaginative: Students "play" with language-the sounds of words and the images they convey. Source: Adapted from Pinnell (1985). Oral and Written Discourse Discourse is classified using various dimensions, such as written versus spoken. Other dimensions include register (formal versus informal in tone, vocabulary, and content) and genre (a combination of communicative purpose, audience, and format) as well as considerations of number-monologic, dialogic, or multiparty (how many are involved) (Celce-Murcia & Olshtain, 2001). Many kinds of analysis have been used in examining discourse: studies of information structure, coherence, cohesion, turn-taking, and critical discourse analysis. Discourse analysis can be defined as the study of language "beyond the sentence." Discourse might be characterized as "language associated with a particular activity, a particular kind of knowledge, a particular group of people or a particular institution" (Peim, 1993, p. 194). The study of discourse looks at language in its larger units, such as oral text (classroom talk, speeches, casual conversation) and written text (magazine articles, school assignments, signs, and posters). Discourse specialists have looked at such behavior as how people take turns, how speakers use contextual cues as they interact, and how people show others they are listening. These features are heavily influenced by culture. The Discourse of Academia What does it mean to use language for academic purposes? An educated person lives in a world in which discourse is used for a wide range of purposes. For many, literacy at work has become highly computer dependent, with word processing, databases, telephone number files, e-mail, and Internet-based activities, as well as paper dependent, with piles of various folders containing information, along with books, journals, and newsletters. At home, personal literacy may include cookbooks, hobby materials, newsmagazines, correspondence, and bill-paying. All these reading materials have their own place, time, and task orientation. Literacy practices are activities that form discourses within the culture or society at large. By the time a student enters undergraduate education, the discourse demands are intense: reading course syllabi, textbooks, study guides, handouts, laboratory manuals, tests, online materials, and reference materials; listening to lectures and peer discussions; writing tests, research papers, and other notes; making formal oral presentations; and informally contributing orally in class or in group working sessions. English learners must prepare for these discourse registers and activities in elementary and secondary school programs. The demands of producing and understanding academic discourse depend not only on acquiring cognitive academic language proficiency, but also on developing qualities such as persistence, rapport with one's teachers, and attunement to the demands of the task, as well as the ability to seek, obtain, and benefit from help. These personality features help an individual accommodate the demands of a situation. Success in previous schooling makes present and future accommodations easier. The peer culture must sustain patterns of academic activity; the parental/cultural standards of achievement must also be appropriately demanding and supportive; and the school must enforce high educational standards, with expert management, well-certified staff, and adequate resources. In this way, the individual is situated within a social and cultural context that sustains academic activity. Oral Discourse in the Classroom Classroom discourse is a special type of conversation. Intonation, pausing, and phrasing determine when one person's turn to speak is over and the next person's turn begins. Markers signal the circulation of power. As Foucault (1979) noted, discursive practices in the modern world prepare the individual for power. Schooling can shape an average person into a "good" student using discourse. Good language learners are able to gain access to a variety of conversations in their communities. The communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) in which they participate-even peripherally-provide access to the utterances of others and the cultural practices they need to become engaged in community life. This means that the community of practice in a classroom does as much to create a good learner as the individual's cognition and striving. Linguistic features are useful ways to examine classroom discourse. Turn markers governing who takes the floor signal speaking and listening. Some listeners nod frequently, and others offer eye contact or feedback such as "hmm," "uh huh," and "yeah." If a teacher is speaking, the type of listening that a learner signals is an important part of that learner's image in the mind of the teacher. If someone seems uninterested or uncomprehending (whether or not they truly are), the speaker tends to slow down, repeat, or overexplain, giving the impression of "talking down." The Recitation Pattern: A Typical Learning Encounter Classrooms in the United States often follow a model of instruction based on recitation. Typically, the pattern has three parts, called the IRE sequence. First, the teacher initiates (1) an interaction by asking a question. A student responds (R), and the teacher follows up with evaluation (E). Alternatively, this may be called the IRF pattern, replacing the term evaluation with feedback (F), which consists not only of praise or disguised evaluation but also of reformulation, repetition of the student's answer, and summarizing or delivering information. The IRE pattern shares characteristics of other kinds of teacher talk. The teacher not only produces the most language but also takes the most turns. Questions asked in this way usually call for simple information recall, and the responses are limited to this type of thinking. The teacher tends to ask "known-answer" questions in which students' responses can be easily evaluated (Pridham, 2001). The IRE pattern is easy to identify, partially because of its prevalence. Invitation to respond: Teacher: Who knows why names are capitalized? (Some students are wildly waving their hands, begging to be chosen to respond; others are averting their eyes, hoping not to be called on) Alma? Response: Alma: It's somebody's name. Evaluation or Feedback: Teacher: That's true. Good, Alma. Invitation to respond: (pattern repeats)... Teacher: But who can tell me what the term for that is? The IRE is not the only discourse pattern in which the teacher dominates, but it is the most frequent. In teacher-fronted classrooms in general, the teacher takes the central role in controlling the flow of information, and students compete for attention and permission to speak. English learners are dependent on their ability to understand the teacher's explanations and directions. Clearly the IRE pattern has positive instructional features-to activate students' prior knowledge about a topic, review material already covered, present new information, calm a noisy room, check on the general state of group knowledge on a topic, or evaluate the discipline and cooperation of individual students. This evaluation of the student seems to shape a teacher's academic expectations for that student. Many features of the recitation pattern work for the benefit of instruction, although the same features that benefit some students may create difficulties for English learners (see Table 2.11 D). Table 2.11 Positive and Negative Features of the IRF for English Learners Positive Features Teacher waits for silence and imposes order on student behavior. Possible Negative Features for English Learners Invitation to Bid English learners may not appear as attentive as English speakers because they might have difficulty comprehending instruction. Teacher controls the scope of the lesson by asking selected questions. Teacher determines order and importance of information by posing questions. Teacher controls the level of language displayed in class by choice of lexicon and complexity of sentence structure. Teacher controls pace and rhythm of discourse. Students can practice risk-taking by volunteering to answer. Students can show knowledge whether from prior instruction or experience. Teacher evaluates behavior of individuals by looking to see who is willing and ready to participate. English learners may be reluctant to bring attention to themselves because they are insecure about their oral language, see such an action as incompatible with group Teacher controls potential for reward by choosing respondent. cohesiveness and cultural norms, or are reluctant to display knowledge in front of others. By acting eager to answer, students can demonstrate Students may lack experience in particular topics under discussion, although their responsivity to instruction, attention, and cooperation even if they background may be rich in topics that are not curriculum related. do not really know the answer the teacher expects to hear. Teacher controls behavior by calling on students who may not Students from cultures in which children do not make direct eye contact with adults may not appear attentive during instruction. be attentive. Teacher is able to evaluate students' level of oral participation. Teacher is able to use teacher approval as a reinforcer. Teacher is able to establish public recognition for those who answer correctly. Teacher may use the evaluation turn to correct sentence grammar. Teacher can withhold negative evaluation by partially accepting an incomplete answer. Teacher can avoid direct negative evaluation by asking one student to "help" another to improve an answer. Teacher may evaluate students' success in the recitation pattern as an indicator of facility with "display knowledge" cultural pattern. English learners may need more time than English speakers to understand questions and frame responses. Students with creative and individualistic thinking may wish to contribute related ideas outside the scope of the immediate topic. Instructional language, including vocabulary, may be too complex for English learners. Pace and rhythm of discourse may be different in students' native language, causing discomfort. Teacher can elaborate on answer and expand a concept by delivering direct instruction at this point. Teacher can improve a poor answer by substituting more correct terminology or restating a sentence in more correct grammar. As teacher evaluates students' responses, he or she determines what question comes next. Response English learners may be reluctant to volunteer to answer if they are not 100 percent sure their idea is correct and their culture does not reward ambiguity. Evaluation (Feedback) Students may need prior language development in oral participation, including turn- taking, listening, and speaking. Students from certain cultures may not depend on teacher for approval. Individual public recognition may be taboo in some cultures. Research shows that second-language grammar is not improved by public correction of grammar, but by gradual acquisition of forms during language input and output. Indirect negative evaluation may be confusing for some students, leaving them with unclear concept formation. Students who are unfamiliar with "display knowledge" cultural pattern may appear uncooperative. Students who are not rewarded by encouragement of more complex questions and responses gradually receive fewer hours of attention and instruction. Recitation Pattern: Questioning Strategies Through skilled questioning, teachers lead discussions and ascertain students' understanding. Questions should be framed to match students' proficiency levels and to evoke the level of critical or creative thinking sought in