Question: Ferrell & Gresham (1985), A Contingency Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Marketing, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 (Summer), pp. 87-96. Just Try and

Ferrell & Gresham (1985), A Contingency Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Marketing, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 (Summer), pp. 87-96.

Just Try and Social Distance This, Bloomberg Businessweek, April 20, 2020, p.40-45.

- Stakeholders are directly or indirectly affected by an organizations actions. Provide 3 specific stakeholders affected by ethical situation and briefly explain the effect(s).

- Discuss the challenges in addressing the ethical dilemma faced by Donald by identifying at least 2 key issues and their subsequent implications/ramifications.

- If you were Donald, how would you have responded to the ethical dilemma?

- If you were part of Carnivals top management, how would you implement a solution to respond to the ethical dilemma?

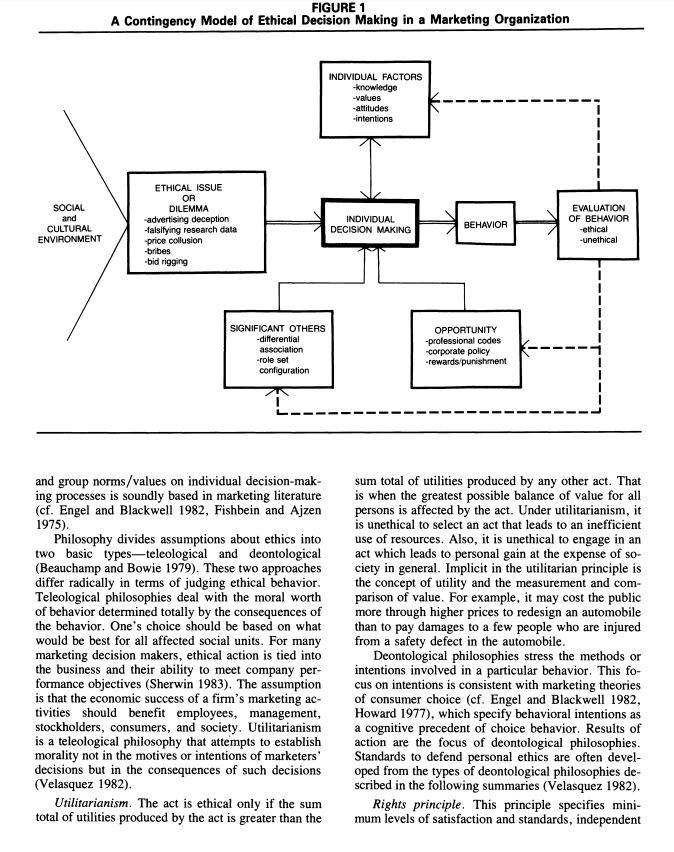

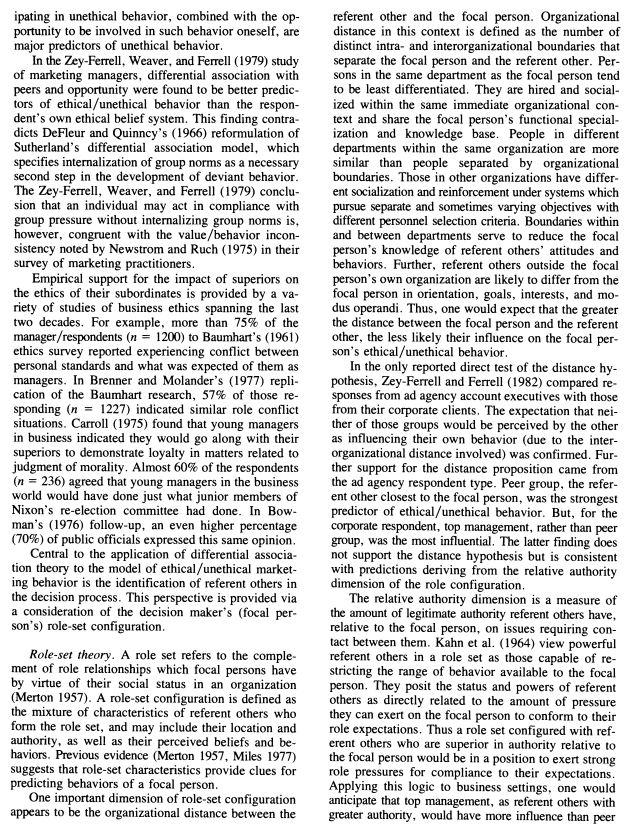

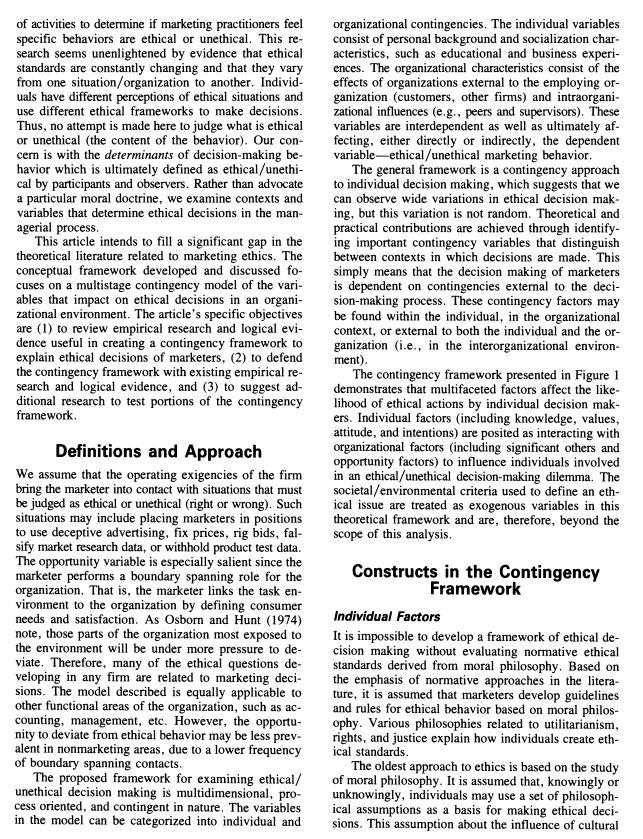

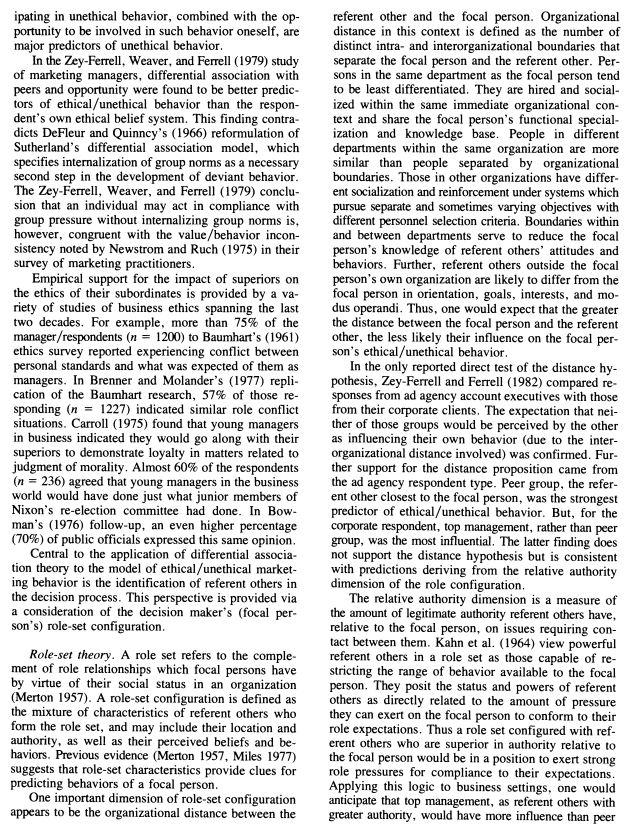

A Contingency Framework for Understanding Ethical Decision Making in Marketing This article addresses a significant gap in the theoretical literature on marketing ethics. This gap results from the lack of an integrated framework which clarifies and synthesizes the multiple variables that ex- plain how marketers make ethical/unethical decisions. A contingency framework is recommended as a starting point for the development of a theory of ethical/unethical actions in organizational environments. This model demonstrates how previous research can be integrated to reveal that ethical/unethical de- cisions are moderated by individual factors, significant others within the organizational setting, and op- portunity for action. OST people agree that a set of moral principles ing decision makers, and most marketers would agree that their decisions should be made in accordance with accepted principles of right and wrong. However, consensus regarding what constitutes proper ethical behavior in marketing decision situations diminishes as the level of analysis proceeds from the general to the specific (Laczniak 1983a). For example, most people would agree that stealing by employees is wrong. But this consensus will likely lessen, as the value of what is stolen moves from embezzling com- pany funds, to "padding" an expense account, to pil- fering a sheet of poster board from company supplies for a child's homework project. In fact, a Gallup poll found that 74% of the business executives surveyed had pilfered homework supplies for their children and 78% had used company telephones for personal long- distance calls (Ricklefs 1983a). Because of the lack of agreement concerning eth- ical standards, it is difficult to find incidents of de- viant behavior which marketers would agree are unethical. For example, in the Gallup poll cited above, 31% had ethical reservations in accepting an expen- sive dinner from a supplier, but most of the respon- dents indicated that bribes, bid rigging, and price col- lusion had become more common in recent years (Ricklefs 1983a, 1983b). Dishonesty is reportedly perverting the results of market tests (Hodock 1984). Obviously, there is a wide-ranging definition of what is considered to be ethical behavior among marketing practitioners. Absence of a clear consensus about what is ethical conduct for marketing managers may lead to delete- rious results for a business. Due to faulty test mar- keting results, potentially successful products may be scrapped and unwise market introductions may be made. In either case, both the consumer and the "cheated" firm are losers. Productivity and other mea- sures of efficiency may be low because employees maximize their own welfare rather than placing com- pany goals as priorities. Absence of a clear consensus about ethical con- duct among marketers has resulted in much confusion among academicians who study marketing ethics. These academicians have resorted to analyzing various lists 0. C. Ferrell is Associate Professor, and Larry G. Gresham is Assistant Professor, Department of Marketing, Texas A&M University. The au- thors wish to thank Patrick E. Murphy, Gene R. Laczniak, Mary Zey. Ferrell, Charles S. Madden, Steven Skinner, Terry Childers, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and constructive comments. of activities to determine if marketing practitioners feel specific behaviors are ethical or unethical. This re- search seems unenlightened by evidence that ethical standards are constantly changing and that they vary from one situation/organization to another. Individ- uals have different perceptions of ethical situations and use different ethical frameworks to make decisions. Thus, no attempt is made here to judge what is ethical or unethical (the content of the behavior). Our con- cern is with the determinants of decision-making be- havior which is ultimately defined as ethical/unethi- cal by participants and observers. Rather than advocate a particular moral doctrine, we examine contexts and variables that determine ethical decisions in the man- agerial process This article intends to fill a significant gap in the theoretical literature related to marketing ethics. The conceptual framework developed and discussed fo- cuses on a multistage contingency model of the vari- ables that impact on ethical decisions in an organi- zational environment. The article's specific objectives are (1) to review empirical research and logical evi- dence useful in creating a contingency framework to explain ethical decisions of marketers, (2) to defend the contingency framework with existing empirical re- search and logical evidence, and (3) to suggest ad- ditional research to test portions of the contingency framework. organizational contingencies. The individual variables consist of personal background and socialization char- acteristics, such as educational and business experi- ences. The organizational characteristics consist of the effects of organizations external to the employing or- ganization (customers, other firms) and intraorgani- zational influences (e.g., peers and supervisors). These variables are interdependent as well as ultimately af- fecting, either directly or indirectly, the dependent variable-ethical/unethical marketing behavior. The general framework is a contingency approach to individual decision making, which suggests that we can observe wide variations in ethical decision mak- ing, but this variation is not random. Theoretical and practical contributions are achieved through identify- ing important contingency variables that distinguish between contexts in which decisions are made. This simply means that the decision making of marketers is dependent on contingencies external to the deci- sion-making process. These contingency factors may be found within the individual, in the organizational context, or external to both the individual and the or- ganization (i.e., in the interorganizational environ- ment). The contingency framework presented in Figure 1 demonstrates that multifaceted factors affect the like- lihood of ethical actions by individual decision mak- ers. Individual factors (including knowledge, values, attitude, and intentions) are posited as interacting with organizational factors including significant others and opportunity factors) to influence individuals involved in an ethical/unethical decision-making dilemma. The societal/environmental criteria used to define an eth- ical issue are treated as exogenous variables in this theoretical framework and are, therefore, beyond the scope of this analysis. Definitions and Approach We assume that the operating exigencies of the firm bring the marketer into contact with situations that must be judged as ethical or unethical (right or wrong). Such situations may include placing marketers in positions to use deceptive advertising, fix prices, rig bids, fal- sify market research data, or withhold product test data. The opportunity variable is especially salient since the marketer performs a boundary spanning role for the organization. That is, the marketer links the task en- vironment to the organization by defining consumer needs and satisfaction. As Osborn and Hunt (1974) note, those parts of the organization most exposed to the environment will be under more pressure to de- viate. Therefore, many of the ethical questions de veloping in any firm are related to marketing deci- sions. The model described is equally applicable to other functional areas of the organization, such as ac- counting, management, etc. However, the opportu- nity to deviate from ethical behavior may be less prev. alent in nonmarketing areas, due to a lower frequency of boundary spanning contacts. The proposed framework for examining ethical/ unethical decision making is multidimensional, pro- cess oriented, and contingent in nature. The variables in the model can be categorized into individual and Constructs in the Contingency Framework Individual Factors It is impossible to develop a framework of ethical de- cision making without evaluating normative ethical standards derived from moral philosophy. Based on the emphasis of normative approaches in the litera- ture, it is assumed that marketers develop guidelines and rules for ethical behavior based on moral philos- ophy. Various philosophies related to utilitarianism, rights, and justice explain how individuals create eth- ical standards. The oldest approach to ethics is based on the study of moral philosophy. It is assumed that, knowingly or unknowingly, individuals may use a set of philosoph- ical assumptions as a basis for making ethical deci- sions. This assumption about the influence of cultural FIGURE 1 A Contingency Model of Ethical Decision Making in a Marketing Organization INDIVIDUAL FACTORS -knowledge -values -attitudes -intentions SOCIAL and CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT ETHICAL ISSUE OR DILEMMA -advertising deception -falsifying research data -price collusion -bribes INDIVIDUAL DECISION MAKING BEHAVIOR EVALUATION OF BEHAVIOR -ethical -unethical bid rigging SIGNIFICANT OTHERS -differential association -role set configuration OPPORTUNITY -professional codes -corporate policy -rewards punishment and group norms/values on individual decision-mak- ing processes is soundly based in marketing literature (cf. Engel and Blackwell 1982, Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). Philosophy divides assumptions about ethics into two basic typesteleological and deontological (Beauchamp and Bowie 1979). These two approaches differ radically in terms of judging ethical behavior. Teleological philosophies deal with the moral worth of behavior determined totally by the consequences of the behavior. One's choice should be based on what would be best for all affected social units. For many marketing decision makers, ethical action is tied into the business and their ability to meet company per- formance objectives (Sherwin 1983). The assumption is that the economic success of a firm's marketing ac- tivities should benefit employees, management, stockholders, consumers, and society. Utilitarianism is a teleological philosophy that attempts to establish morality not in the motives or intentions of marketers' decisions but in the consequences of such decisions (Velasquez 1982). Utilitarianism. The act is ethical only if the sum total of utilities produced by the act is greater than the sum total of utilities produced by any other act. That is when the greatest possible balance of value for all persons is affected by the act. Under utilitarianism, it is unethical to select an act that leads to an inefficient use of resources. Also, it is unethical to engage in an act which leads to personal gain at the expense of so- ciety in general. Implicit in the utilitarian principle is the concept of utility and the measurement and com- parison of value. For example, it may cost the public more through higher prices to redesign an automobile than to pay damages to a few people who are injured from a safety defect in the automobile. Deontological philosophies stress the methods or intentions involved in a particular behavior. This fo- cus on intentions is consistent with marketing theories of consumer choice (cf. Engel and Blackwell 1982, Howard 1977), which specify behavioral intentions as a cognitive precedent of choice behavior. Results of action are the focus of deontological philosophies. Standards to defend personal ethics are often devel- oped from the types of deontological philosophies de scribed in the following summaries (Velasquez 1982). Rights principle. This principle specifies mini- mum levels of satisfaction and standards, independent of outcomes. Moral rights are often perceived as uni- versal, but moral rights are not synonymous with legal rights. The rights principle is based on Kant's cate- gorical imperative which basically incorporates two criteria for judging an action. First, every act should be based on a reason(s) that everyone could act on, at least in principle (universality). The second crite- rion is that action must be based on reasons the actor would be willing to have all others use, even as a basis of how they treat the actor (reversibility). For example, consumers claim that they have a right to know about probable defects in an automobile that relate to safety Justice principle. This principle is designed to protect the interests of all involved. The three cate- gories are distributive, retributive, and compensatory. Basically, distributive justice holds that equals should be treated equally and unequals should be treated un- equally. Retributive justice deals with blaming and punishing persons for doing wrong. The person must have committed the act out of free choice and with knowledge of the consequences. The punishment must be consistent with or proportional to the wrongdoing. Compensatory justice is concerned with compensation for the wronged individual. The compensation should restore the injured party to his/her original position. Corporate hierarchies and executive prerogatives are examples of distributive justice in practice. Antitrust legislation allowing criminal prosecution of corporate officials is based on the notion of retributive justice. Class action suits embody compensatory principles It is important to note that all of these philosophies produce standards to judge the act itself, the actor's intentions, or the consequences of the act. Also, these philosophies are based on assumptions about how one should approach ethical problems. Standards devel- oped from utilitarianism, justice principles, and rights principles are used to socialize the individual to act ethically and may be learned with no awareness that the standards are being used. The precise impact of these philosophies on ethical behavior is unknown, but there is widespread acceptance in the marketing lit- erature that such culturally derived standards impact on the decision-making process. Ethical decision making may be influenced by the Individual Factors identified in Figure 1. Beliefs may serve as inputs affecting attitude formation/change and intentions to resolve problems. Also, evaluation or in- tention to act (or even think about an ethical dilemma) may be influenced by cognitive factors that result from the individual's socialization processes. It is at this stage that cultural differences would influence per- ceptions of problems. For example, variations in eth- ical standards are illustrated by what Mexicans call la mordidathe bite. The use of payoffs and bribes are commonplace to business and government officials and are often considered tips for performing required functions. U.S. firms often find it difficult to compete in foreign environments that do not use American moral philosophies of decision making. Organizational Factors The preceding discussion explored philosophies that have an impact on individuals' knowledge, values, at- titudes, and intentions toward ethical issues. In this section, recognition is given to the fact that ethics is not only a matter of normative evaluation, but is also a series of perceptions of how to act in terms of daily issues. From a positive perspective, success is deter- mined by managers everyday performances in achieving company goals. According to Cavanaugh (1976, p. 100), "Pressure for results, as narrowly measured in money terms, has increased." Laczniak (1983a) suggests that this pressure to perform is par- ticularly acute at levels below top management be- cause "areas of responsibility of middle managers are often treated as profit centers for purposes of evalu- ation. Consequently, anything that takes away from profit-including ethical behavior-is perceived by lower level management as an impediment to orga- nizational advancement and recognition" (p. 27). Thus, internal organizational pressures seem to be a major predictor of ethical/unethical behavior. Significant Others Figure 1 posits Significant Others as a contingency variable in individual decision making. Individuals do not learn values, attitudes, and norms from society or organizations but from others who are members of disparate social groups, each bearing distinct norms, values, and attitudes. Aspects of differential associ- ation theory and role-set theory provide theoretical ra- tionales for including organizational factors in the de- cision framework. These theories, and empirical tests of their relevance to the ethical decision-making pro- cess, are discussed in the following sections. Differential association theory. Differential asso- ciation theory (Sutherland and Cressey 1970) assumes that ethical/unethical behavior is learned in the pro- cess of interacting with persons who are part of inti- mate personal groups or role sets. Whether or not the learning process results in unethical behavior is con- tingent upon the ratio of contacts with unethical pat- terns to contacts with ethical patterns. Cloward and Ohlin (1960) are responsible for incorporating an op- portunity variable (discussed in a later section) in the differential association model of deviant behavior. Thus, as posited in our model, it is expected that as- sociation with others who are perceived to be partic- ipating in unethical behavior, combined with the op- portunity to be involved in such behavior oneself, are major predictors of unethical behavior. In the Zey-Ferrell, Weaver, and Ferrell (1979) study of marketing managers, differential association with peers and opportunity were found to be better predic- tors of ethical/unethical behavior than the respon- dent's own ethical belief system. This finding contra- dicts DeFleur and Quinncy's (1966) reformulation of Sutherland's differential association model, which specifies internalization of group norms as a necessary second step in the development of deviant behavior. The Zey-Ferrell, Weaver, and Ferrell (1979) conclu- sion that an individual may act in compliance with group pressure without internalizing group norms is. however, congruent with the value/behavior incon- sistency noted by Newstrom and Ruch (1975) in their survey of marketing practitioners. Empirical support for the impact of superiors on the ethics of their subordinates is provided by a va- riety of studies of business ethics spanning the last two decades. For example, more than 75% of the manager/respondents (n = 1200) to Baumhart's (1961) ethics survey reported experiencing conflict between personal standards and what was expected of them as managers. In Brenner and Molander's (1977) repli- cation of the Baumhart research, 57% of those re- sponding (n = 1227) indicated similar role conflict situations. Carroll (1975) found that young managers in business indicated they would go along with their superiors to demonstrate loyalty in matters related to judgment of morality. Almost 60% of the respondents (n = 236) agreed that young managers in the business world would have done just what junior members of Nixon's re-election committee had done. In Bow- man's (1976) follow-up, an even higher percentage (70%) of public officials expressed this same opinion. Central to the application of differential associa- tion theory to the model of ethical/unethical market- ing behavior is the identification of referent others in the decision process. This perspective is provided via a consideration of the decision maker's (focal per- son's) role-set configuration. Role-set theory. A role set refers to the comple- ment of role relationships which focal persons have by virtue of their social status in an organization (Merton 1957). A role-set configuration is defined as the mixture of characteristics of referent others who form the role set, and may include their location and authority, as well as their perceived beliefs and be haviors. Previous evidence (Merton 1957, Miles 1977) suggests that role-set characteristics provide clues for predicting behaviors of a focal person. One important dimension of role-set configuration appears to be the organizational distance between the referent other and the focal person. Organizational distance in this context is defined as the number of distinct intra- and interorganizational boundaries that separate the focal person and the referent other. Per- sons in the same department as the focal person tend to be least differentiated. They are hired and social- ized within the same immediate organizational con- text and share the focal person's functional special- ization and knowledge base. People in different departments within the same organization are more similar than people separated by organizational boundaries. Those in other organizations have differ- ent socialization and reinforcement under systems which pursue separate and sometimes varying objectives with different personnel selection criteria. Boundaries within and between departments serve to reduce the focal person's knowledge of referent others' attitudes and behaviors. Further, referent others outside the focal person's own organization are likely to differ from the focal person in orientation, goals, interests, and mo- dus operandi. Thus, one would expect that the greater the distance between the focal person and the referent other, the less likely their influence on the focal per- son's ethical/unethical behavior. In the only reported direct test of the distance hy- pothesis, Zey-Ferrell and Ferrell (1982) compared re- sponses from ad agency account executives with those from their corporate clients. The expectation that nei- ther of those groups would be perceived by the other as influencing their own behavior (due to the inter- organizational distance involved) was confirmed. Fur- ther support for the distance proposition came from the ad agency respondent type. Peer group, the refer- ent other closest to the focal person, was the strongest predictor of ethical/unethical behavior. But, for the corporate respondent, top management, rather than peer group, was the most influential. The latter finding does not support the distance hypothesis but is consistent with predictions deriving from the relative authority dimension of the role configuration. The relative authority dimension is a measure of the amount of legitimate authority referent others have, relative to the focal person, on issues requiring con- tact between them. Kahn et al. (1964) view powerful referent others in a role set as those capable of re- stricting the range of behavior available to the focal person. They posit the status and powers of referent others as directly related to the amount of pressure they can exert on the focal person to conform to their role expectations. Thus a role set configured with ref- erent others who are superior in authority relative to the focal person would be in a position to exert strong role pressures for compliance to their expectations. Applying this logic to business settings, one would anticipate that top management, as referent others with greater authority, would have more influence than peer groups on the focal person's ethical/unethical behav- ior. The Baumhart (1961) and Brenner and Molander (1977) surveys support this relative authority propo- sition--behavior of superiors was perceived by re- spondents in both studies as the number one factor influencing ethical/unethical decisions. Similar re- sults are also reported in a study by Newstrom and Ruch (1975). Hunt, Chonko, and Wilcox (1984) found the actions of top management to be the single best predictor of perceived ethical problems of marketing researchers. Ferrell and Weaver (1978) suggest that top management must assume at least part of the re- sponsibility for the ethical conduct of marketers within their organization. In addition, the general conclusion that the ethical tone for an organization is set by upper management is common to most attempted syntheses of ethics research (cf. Dubinsky, Berkowitz, and Ru- delius 1980; Laczniak 1983a; Murphy and Laczniak 1981). Responses from the Zey-Ferrell and Ferrell (1982) ad agency executive sample do not support the au- thority proposition-this group was influenced by peers, rather than top management. The authors spec- ulate that this unexpected outcome may have been at- tributable to the high frequency of contact among ad agency account executives and their relatively infre- quent associations with superiors. Such an explana- tion is congruent with differential association theory and appears to indicate that frequency of contact with referent others is a more powerful predictor (than rel- ative authority) of ethical/unethical behavior. Corpo- rate client responses from the same survey also sup- port a differential association explanation of the results obtained-top management, rather than peers, was perceived as the relevant referent other. In a corpo- ration, the advertising director does not have a num- ber of individuals at the same level with whom to in- teract. Thus, the frequency of interaction with upper management levels is usually higher for advertisers in corporations because the advertising director does not have anyone else performing the same job tasks. Opportunity Figure 1 depicts opportunity as having a major impact on the process of unethical/ethical decision making. Opportunity results from a favorable set of conditions to limit barriers or provide rewards. Certainly the ab- sence of punishment provides an opportunity for unethical behavior without regard for consequences. Rewards are external to the degree that they bring social approval, status, and esteem. Feelings of good- ness and worth, internally felt through the perfor- mance of altruistic activities, for example, constitute internal rewards. External rewards refer to what an individual in the social environment expects to receive from others in terms of values externally generated and provided on an exchange basis. It is important to note that deontological frameworks for marketing eth- ics focus more on internal rewards, while teleological frameworks emphasize external rewards. Cloward and Ohlin (1960) are responsible for in- corporating an opportunity variable in the differential association model of ethical/unethical behavior. Zey. Ferrell and Ferrell (1982) empirically confirm that the opportunity of the focal person to become involved in ethical/unethical behavior will influence reported be- havior. In this study, opportunity for unethical be- havior was found to be a better predictor of behavior than personal or peer beliefs. Therefore, we can con- clude that professional codes of ethics and corporate policy are moderating variables in controlling oppor- tunity Weaver and Ferrell (1977) suggest that codes of ethics or corporate policy on ethics must be estab- lished to change individual beliefs about ethics. Their research indicates that beliefs are more ethical where these standards exist. Also, it was found that the en- forcement of corporate policy on ethical behavior is necessary to change the ethical behavior of respon- dents. Their research discovered a poor correlation between ethical beliefs and ethical behavior. Oppor- tunity was a better predictor of ethical behavior than individual beliefs. This research supports the need to understand and control opportunity as a key deter- minant (as indicated in Figure 1) in a multistage con- tingency model of ethical behavior. A Contingency Framework for Ethical Decisions A contingency framework for investigating behavioral outcomes of ethical/unethical decisions across situa- tions is shown in Figure 1. The basic elements of the framework are: (a) the individual's cognitive struc- ture-knowledge, values, beliefs, attitudes, and in- tentions; (b) significant others in the organizational setting; and (c) opportunity for action. Figure 1 specifies that the behavioral outcome of an ethical dilemma is related to the first order inter- action between the nature of the ethical situation and characteristics associated with the individual and the organizational environment. Potential higher order in- teractions are anticipated in the basic postulate. At this stage of development, there is no claim that this is an all-inclusive framework; rather, it is the initial step toward constructing such a framework. Propositions from the contingency Framework Each of the constructs associated with the framework were discussed in the preceding sections. Some prop- ositions incorporating the previously defined con- b. Corporate policy and codes of ethics that are en- forced will produce the highest level of compli- ance to established ethical standards. c. The greater the rewards for unethical behavior, the more likely unethical behavior will be practiced. d. The less punishment for unethical behavior, the greater the probability that unethical behavior will be practiced. structs are presented in the section that follows. These propositions are stated so that testable hypotheses can be derived to direct future research efforts. The ele- ments and propositions discussed were selected on the basis of the past research and logical evidence used to construct the contingency framework in Figure 1. They are presented as a representative subset of po- tential propositions that can be derived from the par- adigm. Propositions Concerning the Individual factors Proposition 1: The more individuals are aware of moral philosophies for ethical decision making, the more in- fluence these philosophies will have on their ethical decision a. Individuals will be influenced by moral philoso- phies learned through socialization, i.e., family, social groups, formal education. b. Within the educational system, courses, training programs, and seminars related to ethics will in- fluence ethical beliefs and behavior c. The cultural backgrounds of individuals will influ- ence ethical/unethical behavior. Propositions concerning Organizational Factors Proposition 2: Significant others located in role sets with less distance between them and the focal indi- vidual are more likely to influence the ethical behav- ior of the focal person a. Top management will have greater influence on the individual than peers, due to power and demands for compliance. b. Where top management has little interaction with the focal person and peer contact is frequent, peers will have a greater influence on ethical behavior. Proposition 3: In general, differential association (learning from intimate groups or role sets) predicts ethical/unethical behavior. a. Internalization of group norms is not necessary to develop ethical/unethical behavior through differ- ential association b. Unethical behavior is influenced by the ratio of contacts with unethical patterns to contacts with ethical patterns. Propositions Concerning the Opportunity Variable Proposition 4: The opportunity for the individual to become involved in unethical behavior will influence reported ethical/unethical behavior. a. Professional codes of ethics will influence ethical/ unethical behavior. Ethics related corporate policy will influence ethical/unethical behavior. Developing and Testing Contingency Propositions The research program for developing and testing con- tingency hypotheses outlined by Weitz (1981) pro- vides valuable guidance for future studies of market- ing ethics. This program, recommended for tests of his contingency framework of effectiveness in sales interactions, is adaptable to examinations of ethical phenomena. The three stages of the research program are hypotheses generation, hypotheses testing in a lab- oratory environment, and hypotheses testing in a field setting Hypotheses Generation The primary objectives of this step in the research program are to (1) add specificity to the propositions presented in the preceding section, i.e., move from "bridge laws" (Hunt 1983, p. 195) to research hy- potheses; (2) identify additional propositions from the theoretical framework; and (3) develop a richer tax- onomy of moderator variables within the Individual Factors. Significant Others, and Opportunity subsets. Past studies of business ethics (cf. Darden and Trawick 1980; Dubinsky, Berkowitz, and Rudelius 1980), with their foci on identifying perceptions of ethical/unethical situations, provide a useful starting point for achieving the first objective of adding spec- ificity to propositions. The theoretical framework of ethical decision making developed in this article re- quires identification of a variety of ethical issues to make the hypotheses derived from the specified re- lationships empirically testable. In addition, the prac- tical and theoretical value of the proposed contin- gency framework can only be determined by testing its explanatory power across a variety of ethical sit- uations. Theories in use methodologies (Zaltman, Le- Masters, and Heffring 1982) might be useful in gen- erating additional theoretical propositions and devel- oping a richer taxonomy of moderator variables, as well as in identifying a wide range of ethical dilem- mas. Such methodologies involve observing and questioning marketing decision makers. Examples of how these techniques might be employed in ethics re- search include studies of verbal protocols recorded during the decision-making process, interviews with marketing practitioners concerning their behavior in specific decision situations, and investigations of the characteristics marketers use to classify ethical/uneth- ical situations. Levy and Dubinsky (1983) have de- veloped a methodology for studying retail sales ethics that applies the protocol technique. Their approach starts by generating situations that might be ethically trou- blesome to the retailer's sales personnel. This is first addressed by meeting with 8 to 12 retail sales per- sonnel from different departments with a moderator to generate, individually and silently, ethical prob- lems they confront on their jobs, and to record these on a sheet of paper. Experimental Testing Regardless of the procedure used to develop contin- gency hypotheses from the theoretical framework, the next step in the ethics research program is to test these hypotheses in a laboratory environment, using an ex- perimental design. The advantages of laboratory ex- periments to researchers attempting to assess causal relationships between variables are widely recognized (cf. Cook and Campbell 1976) as including control of exogenous variables and elimination of potential al- ternative explanations for the results obtained. How- ever, the difficulties involved in testing hypotheses concerning marketing ethics in lab settings is evi- denced by the absence in the marketing/business lit- erature of reports of such experiments. The subjective nature of self-report operationalizations of constructs from the ethical decision-making framework and the problem of achieving experimental realism (Carl- smith, Ellsworth, and Aronson 1976, p. 83) in labo- ratory tests of ethical issues represent major threats to the internal validity of these studies. However, the management literature on collective bargaining contains numerous examples of laborato- ry studies of negotiation techniques (cf. DeNisi and Dworkin 1981, Johnson and Tullar 1972, Notz and Stark 1978), which are very similar to the type of ex- periment needed in ethics research, i.e., unobtrusive, experimenter-controlled predictor variables and clearly defined behavioral outcomes. Such studies illustrate how complex cognitive phenomena (e.g., attitudes) can be operationalized, manipulated, and measured while minimizing threats to internal validity. Applying similar techniques to studies of market- ing ethics might involve, for example, manipulating the opportunity to engage in unethical behavior through the presence/absence of specific experimen- ter instructions regarding the rules of the game, or varying the impact of significant others through the use of a confederate in experimental groups. Labo- ratory experiments represent quick and effective ways for testing behavioral propositions. In addition, the primary value of such studies to a research program for marketing ethics may well lie in the purification of existing measures of the constructs under consid- eration, as well as the development of new and more valid and reliable operationalizations. Field Testing The survey procedures used in earlier tests of some of the relationships posited in the theoretical frame- work of ethical decision making (Zey-Ferrell, Weaver, and Ferrell 1979) represent efficient and practical methods of examining these linkages. However, the correlational nature of the results obtained in these studies prohibits causal inference. In addition, the va- lidity of the self-report measures used in these studies is open to question Future research programs on marketing ethics should address the latter problem in the laboratory testing phase. Lab studies focusing on the purification of existing measures of the constructs of interest and the identification of new and different measurement methods (e.g., physiological measures) may well re- sult in the valid and reliable instruments needed for the field testing portion of the research program. The ethical problems inherent in experimental ma- nipulation of ethical issues/problems in field settings make solutions to the former problem much more dif- ficult to overcome. Some of the hypotheses derived from the propositions presented earlier (e.g., those concerning the effects of corporate policy and training programs/seminars) are more amenable to field test- ing than others. For example, multi-unit corporations might institute training programs/seminars related to ethics at some locations and not at others. Before and after indices of ethical/unethical behavior (e.g., em- ployee theft, customer complaints) could then be compared for the treatment and control units. Cook and Campbell (1976) indicate that "quasi-experimen- tal designs of this sort are acceptable surrogates for "true experiments" in field settings where random as- signment of subjects to treatment control conditions is frequently impossible or impractical. Nevertheless, the ethical issues and practical prob- lems associated with random assignment of subjects to treatment conditions and unobtrusive assessment (or inducement) of ethical/unethical behavior present major obstacles to the implementation of experimental de- signs in field settings. Conclusion Research and theoretical development in marketing ethics have not been based on multidimensional models that are contingent in nature. Most articles in the field of marketing ethics focus on moral philosophies, re- searchers provide descriptive statistics about ethical beliefs, and correlational linkages of selected vari- ables. This article attempts to integrate the key deter- minants of ethical/unethical behavior in a multistage contingency model. The framework is based on the assumption that the behavioral outcome of an ethical dilemma is related to first order interaction between the nature of the ethical situation and characteristics associated with the individual (cognitive factor), sig- nificant others, and opportunity. The framework pro- vides a model for understanding the significance of previous theoretical work and empirical research and provides direction for future studies. The contingency framework is process oriented, with events in a sequence causally associated or in- terrelated. The contingency variables represent situ- tional variables to the marketing decision maker. The complexity and precision of the framework developed in this paper should increase as research is conducted that permits more scientific conclusions about the na- ture of ethical decision making in marketing. Our framework is a start toward developing a comprehen- sive framework of ethical decision making. We have attempted to construct a simple and direct represen- tation of variables based on the current state of re- search and theory development. Propositions concerning individual factors and propositions concerning the organizational factors of significant others and opportunity were developed to be used in a research program for testing contingency hypotheses. Based on a research program for testing contingency hypotheses outlined by Weitz (1981), we suggest hypotheses generation, hypothesis testing in a laboratory environment, and hypothesis testing in a field setting. Both retail store management and field sales management provide excellent opportunities for testing the contingency framework in Figure 1. For example, Dubinsky (1985) has developed a method- ology for studying the ethical problems of field sales- people as an approach for designing company poli- cies. Dubinsky's methodology could be tested using the contingency framework of ethical decision mak- ing, hypotheses generation, laboratory testing, and field testing To develop new directions in research and theory construction, new propositions are needed to test the contingency framework. More research to develop a taxonomy of ethical standards (Velasquez 1982) and attempts to incorporate these standards into marketing (Fritzche 1985) are needed to understand more about individual factors related to beliefs, values, attitudes, or intentions. Attempts to develop logical decision rules for individual decision making (Laczniak 1983b) also contribute to understanding individual factors. Chonko and Burnett (1983) provide an example of descriptive research classifying individual beliefs about sales sit- uations that are a source of role conflict. Their re- search may assist in developing additional proposi- tions, especially as it relates to pinpointing new ethical issues. In addition, marketers should be able to draw from a rich source of research on organizational be- havior to develop and test propositions related to sig- nificant others and opportunity. The importance of ethical decision making in mar- keting is becoming more evident. Laczniak and Mur- phy (1985) suggest organizational and strategic mech- anisms for improving marketing ethics, including codes of marketing ethics, marketing ethics committees, and ethics education modules for marketing managers. To improve specific recommendations for marketing eth- ics, more needs to be learned about the process of ethical decision making. We suggest an integrated ap- proach to understanding marketing ethics with im- proved propositions that test the contingency model presented in this article. By taking a multidimensional view of ethical decision making, a new level of rigor in research should be achieved. Bloomberg Businessweek JUS SO Dis Writt The news, when it reached the Grand Princess early on That day, passengers noticed new hand sanitizer stations March 4, barely registered at first. In a letter slipped under and crew members wearing gloves, but life on the Grand passenger cabin doors, Grant Tarling, Carnival Corp's chief Pri ess, which advertises 1,301 cabins, 20 restaurants and medical officer, announced that the U.S. Centers for Disease lounges, about a dozen shops, and four freshwater swimming Control had begun "investigating a small duster" of Covid-19 pools, otherwise went on as normal. Guests prepared for a cases in California that might have been linked to the ship. ukulele concert, played bridge at shared tables, and took line- Thirteen days after leaving San Francisco for Hawaii, the ves dancing classes. That night, Laurie Miller and her husband, sel would be skipping a scheduled stop in Mexico on its return John, attended True or Moo, a show featuring an emcee in a voyage and sailing back early to its Bay Area port. cow costume; the following morning, John joined about 200 they hada Covid 19 problem. They kept the party going as long as possible By Austin Carrand Chris Palmeri nd ca tance IS 11 ve other passengers in the ship's Broadway-style theater for a my God," she remembers thinking. "This is real." Then she lecture on Clint Eastwood movies. I'm surprised they're even ordered more ice cream. letting this event happen," he whispered to a nearby friend. Other passengers ambled to the ship's stores and dining "This is a big crowd." areas, too, to take advantage of the perks while they could. Around lunchtime on March 5, the ship's captain, John "Evverrrybody went to the buffet, recalls 61-year-old Debbi Smith, announced a quarantine over the ship's public Loftus, who was traveling with her parents. I just thought, address system. All 2,422 passengers needed to go to their Oh, crap, the ukulele concert is going to be canceled." Crowds cabins to shelter in place. Laurie Miller was in the Da Vinci of elderly guests filed to their cabins through narrow hallways dining room eating chocolate peanut butter ice cream. Oh and down the stairs of the ship's 17 decks. Sixty-nine-year-old "Nothing's perfect,OK?" 42 Karen Dever tried an elevator Donald Donald and his team say they're only to find it packed with fellow making every effort to protect and treat passengers. "So much for social dis- their remaining passengers. The com- tancing" she joked aloud. pany has attempted to dock its fleet As the lockdown progressed, until the pandemic subsides. All but the ship became a fixture on cable about 3,200 passengers and crew are news and social media around the back on shore. world, livestreamed by frustrated, Carnival's future is less clear. scared passengers as if it were the Australian police have launched a Titanic of the TikTok age. Of the criminal probe into whether the com- first 46 crew and passengers who pany's Princess Cruises subsidiary were tested for the virus, 21 were misled authorities about an outbreak positive. President Trump suggested they should be prevented aboard a ship docked in Sydney, and its Costa Cruises sub- from disembarking. At the time the number of confirmed cases sidiary is facing multiple passenger lawsuits regarding its in the U.S. was still low, and Trump implied that the vessel's Covid-19 response. (Princess says it's cooperating with the caseload would make it look like the U.S. was doing a poor job investigation, while Costa says: "We are prepared to vigor- of handling the pandemic. "I don't need to have the numbers ously defend ourselves.") Carnival canceled all its cruises in double because of one ship," he said. mid-March, and its share price is down 75% so far this year. But this wasn't Carnival's first outbreak, nor its last. In Its executives speak about their next moves in militaristic February, another of its ocean liners, the Diamond Princess, terms. They're setting up "situation rooms," cutting through accounted for more confirmed Covid-19 infections than any the "fog of war;" countering the virus on the front lines." Says nation except for China. Since then no cruise operator has been John Padgett, Carnival's chief experience and innovation offi- hit harder than Carnival. At least seven more of the company's cer: "The cruise space is as bad as it gets. It's Armageddon." ships at sea have become virus hot spots, resulting in more than 1,500 positive infections and at least 39 fatalities. Carnival One side effect of an Armageddon is to render the recent notes that other cruise companies have been impacted." past faintly ridiculous. Last September, in Brooklyn, Padget Carnival's ships have become a floating testament to the boarded another docked ship to show off his company's new viciousness of the new coronavirus and raised questions Medallion Class badges. The electronic fobs were meant to about corporate negligence and fleet safety. President and double as cabin keys and credit cards, while also tracking Chief Executive Officer Arnold Donald says his company's passengers' locations as they moved around the ship. The response was reasonable under the circumstances. "This is offering was part of a big digital overhaul to be introduced a generational global event-it's unprecedented," he says. on at least six ships in 2020. "We're trying to eliminate guest "Nothing's perfect, OK? They will say, "Wow, these things friction," Padgett said. Carnival did great. These things, 20/20 hindsight, they Carnival's business had experienced a remarkable turn- could've done better." around after Donald became CEO in 2013. Over the next Donald says that if his company failed to prepare for the five years, the company's market value roughly doubled, to pandemic, it failed in the same way that many national and $51 billion. In 2017, Donald invested in building a 180,000-ton local governments failed, and should be judged accordingly.megacruiser called the Mardi Gras, Carnival's largest ship "Each ship is a mini-city," he says, and Carnival's response ever, which cost about $1 billion and is supposed to begin shouldn't be condemned before "analyzing what New York sailing in 2020 with the seas' first onboard roller coaster. did to deal with the crisis, what the vice president's task Before the Covid-19 crisis began, the company's nine cruise force did, what the Italians, Chinese, South Koreans, and brands employed 150,000 people. Japanese did. We're a small part of the real story. We're being Carnival was founded in 1972 by Ted Arison, an Israeli pulled along by it." American who wanted to transform the image of the cruise In the view of the CDC, however, Carnival helped fuel the industry from stuffy ultraluxury to a middle-class splurge with crisis. "Maybe that excuse flies after the Diamond Princess, or a party atmosphere. Arison's first ship, also named Mardi Gras, maybe after the Grand Princess," says Cindy Friedman, the had only 300 passengers and got stuck 20 minutes after leav- experienced epidemiologist who leads the CDC's cruise shiping Miami on a sandbar where it remained for 28 hours. In the task force. "I have a hard time believing they're just a victim of 1980s and '90s, Arison's son Micky bought up a string of com- happenstance." While it would have been tough to get every petitors, took the company public, and made his family one of one aboard the ships back to their home ports without infect- the wealthiest in America. By the turn of the century, Carnival ing me ple, Friedman says several of the plagued Carnival owned 36% of the North American market. Micky Arison bought ships didn't even begin their voyages until well after the com- the Miami Heat and became friendly with Donald Trump. pany knew it was risky to do so. She says its actions created (Carnival sponsored The Apprentice more than once.) a "huge strain" on the country. "Nobody should be going on After the Great Recession crippled the cruise business, cruise ships during this pandemic, full stop," she says. Arison began to look like a less capable steward. In 2012, April 20, 2020 sus or Bloomberg Businessweek Carnival's Plagued Ships Carnival's Costa Concordia crashed into a rock formation and Ships with one or more Covid-19 cases sank in the calm seas off Tuscany, killing 32 people, including Ships with passengers a child, while the captain abandoned ship. The following year, -"Ships cleared of passengers a fire in the engine room of the Carnival Triumph, now better known as the poop cruise," left hundreds of guests stranded in the Gulf of Mexico without air conditioning or working Diamond Princess toilets for several days. During both the Tuscany crash and 706 infections the poop cruise, Arison was spotted at Heat games. Arison was facing a shareholder revolt by the time he announced he was stepping down as CEO in favor of Donald, Costa Magica, Costa Favolosa, 10 a board member and former Monsanto Co. executive. (Arison remains Carnival's chairman.) Donald positioned himself as a reformer set on improving coordination between the com- pany's various management teams, but he didn't manage to clean up its record. In 2017 the U.S. Department of Justice fined Carnival's Princess line a record $40 million for dumping oil contaminated waste at sea and falsifying official discharge records to cover it up. Last June, Donald himself entered a guilty plea on behalf of Carnival for violating the terms of its settle ment after authorities discovered that its ships kept on dumping even after the 2017 ruling. "We acknowledge the shortcomings." Donald told a Miami judge. I am here today to formulate a plan to fix them." He would head into 2020 committed, he said, to changing the company's tendency to cut corners on safety. Grand Princess, 103 At 11:12 p.m. Japan Standard Time on Feb. 1, more than a month before the outbreak on the Grand Princess, the Diamond Princess was skimming around Asia on a multiweek cruise. One of its sanitation vendors, Wallem Group, emailed an alert to the vessel's chief administrative officer and a guest Ruby Princess, 660 services inbox. A Wallem representative said a passenger was being treated for Covid-19 in Hong Kong. "Would kindly inform the ship related parties and do the necessary disinfection," the Costa Luminosa, 60 alert read. Unfortunately, and somewhat inexplicably, accord- Costa Victoria, 3 Zaandam, 9 ing to Roger Frizzell, Carnival's chief communications officer, nobody was monitoring those inboxes. He first says the mes- Coral Princess, 12 sages hadn't been read for at least days," then later emails 4/14 that, actually, an employee had read them much sooner. In Carnival's latest version of the timeline, which it revised repeatedly during various interviews over the past several email to Hong Kong health authorities with the subject line weeks, Nancy Chung, a Hong Kong-based director for the "Confirmed Coronavirus Case" that included the passen- Princess line, learned of the positive test a few hours later, ger's name, age, and ward location at Princess Margaret after seeing a report from Now News TV about a hospital Hospital. But Carnival says this was a mistake. "The subject ized coronavirus patient who was understood to have trav-line should've had question mark, question mark, question eled to Hong Kong on a cruise. Chung texted an executive mark, because he was asking if it's confirmed," says Frizzell, in California, who requested she connect Hong Kong health the Carnival spokesman, adding that Tarling didn't get official officials with Tarling, the company's chief medical officer, confirmation until 6:44 p.m. on Feb. 2. Tarling says he didn't according to screenshots of the messages viewed by Bloomberg see the previous day's press release. A spokesman for the Businessweek. The company says these messages show it acted Hong Kong health department notes that in addition to the promptly. But Carnival didn't tell passengers they might have press release, it immediately informed the shipping agent been exposed to the virus until the evening of Feb. 3, about in Hong Kong of the cruise concerned." 43 hours after the initial alert from Wallem was sent. Another 24 hours elapsed before Captain Gennaro Arma There are other inconsistencies that suggest Carnival informed passengers and crew on the Diamond Princess of the wasn't entirely on the ball. The Hong Kong health depart: Covid-19 case. In his announcement, at 6:33 p.m. on Feb. 3, he ment put out a press release announcing the Covid-19 case tried to project calm as the ship cruised toward Yokohama, late on Feb. 1, and at 11:33 a.m. on Feb. 2, Tarling sent an Japan. The guest hadn't reported feeling ill during his time 43 2/1 -ROCONFIRMED CORIS OF AVORAGE ON WECHAPSF LEGO FRONTART NOWTH OVIDED Cruising in Isolation of talenten representing have edittom warenemies,"wypassenger Karen to dropsupplies Cremember wearmadaring Dever: OPengeramure and John Miller the Photographstrompengers the quarantina. Container of food are delivered to the ship. The typicalquarters gearbe were confined to aboard the Grand Princess gabing kapated in their cabins wouldn't weren' especiallyroom on board, Arma said over the loudspeaker, but o in place to take better care of its guests. Some passengers should avoid close contact with any- Grand Princess passengers had to fill out a ques one suffering respiratory illness, wash their hands tionnaire asking if they'd recently been to China, for 20 seconds, and seek treatment from the ship's though there were no questions about whether nurses if they had fever, chills, or a cough. "Rest they had symptoms consistent with Covid-19. assured, there will be no charge for this service," On March 5, after the ship's crew canceled he said. Upon arrival in Yokohama that evening, the ukulele concert and any further games of Japanese health officials started medical screen- True or Moo, the Grand Princess went into a ings. Arma added: "The situation is under control, holding pattern off the San Francisco coast while and therefore there are no reasons for concerns." the White House and state and local officials fig. Even after Carnival became aware of the ured out what to do. Passengers were stuck in potential coronavirus case, passengers say staff their cabins for almost two weeks as helicopters tried to keep the fun going. Guests con- delivered provisions and test kits. tinued eating and drinking at buffets and The Grand Princess pulled into porton bars, hanging out in saunas, and attending March 9 in Oakland, Calif., where the CDC shows, including an operatic performance mostly took over. Like those aboard the called Bravo. Carnival distributed itineraries Diamond Princess, the passengers endured (known as "Princess Patter") guiding guests an additional 14-day quarantine after dis- to trivia contests and other group activities embarking before being allowed to travel on Feb. 3. "They were encouraging us to home. Between the Diamond Princess and mingle," says Gay Courter, who, after get- Grand Princess, 850 people tested positive ting her temperature taken by a Japanese official for Covid-19 and 14 have died. More would fol- the next day, went for a walk on deck and saw low from outbreaks on other ships. tables of as many as 30 people playing mahjong. Asked why Carnival didn't act sooner to ini- A Carnival spokesman says the staff discon- tiate stringent shipwide quarantines, and why tinued "most" scheduled activities on Feb. 4. so many passengers reported being able to though Japanese officials didn't institute a ship- stroll about the ships following alerts of possi. wide quarantine requiring passengers to stay in bly deadly infections, Swartz says the company their cabins until Feb. 5. was following the direction of health authorities The president of Carnival's Princess Cruises "It's very easy and Monday morning, you know, division, Jan Swartz, says the company was 20/20 hindsight, to say what's the view of what deferring to Japanese health officials. She says should have been occurring," she says. "We did the crew followed government guidelines, our best to take care of people." delivering the passengers food and pre-O Carnival executives say they're proud scription refills as the quarantine at of how they served the customers aboard Yokohama's port wore on Carnival CEO these cruises. They refunded everyone's tick Donald says he was aware of the situation ets and onboard purchases, provided free but didn't personally take control of the internet access during the quarantines, and response efforts until Feb. 5. "We have a assisted with post-cruise travel accommo- nice chain of command," he says. "As it dations. Swartz, who notes she's had many became a bigger issue, I'm dialing into the tours of duty in crisis management" during situation updates." her 20 years at Carnival, says she expects the It was an increasingly chaotic period experience to make customers more likely for Carnival. Shortly before the Diamond Princess to cruise with the company, not less. "There problem, there had been a coronavirus scare are many loyal Princess guests who have told aboard one of its ships near Italy, and a second in us that this has actually cemented Princess as mid-February on another Carnival cruise in Asia. their No.1 vacation choice," she says. (Carnival says these were false alarms.) Countries around the world began refusing to allow the com During Bloomberg Businessweek's March 27 pany's boats to dock, fearing they'd spread the phone interview with Swartz, reports sur virus, creating novel challenges for Donald and his faced that four more people had died and at team. "It wasn't like there were protocols, and that least 138 passengers were sick aboard another this was established. You're at sex, you're moving Carnival ship, the Zaandam, part of its Holland people around, and the rules are changing as you America line. Over the following days, the ship 50" he says. He adds that by early March, when the lingered near the coast of Fort Lauderdale wait virus hit the Grand Princess, Carnival had systems ing for government permission to dock at Port Bloomberg Business April 20, 2020 Everglades, Fla. Yadira Garza, who embarked on the Zaandam a record in any shape, form, or fashion of being unhealthy, of for her honeymoon, says from the ship that she and her hus- guests on our ships being more ill than in other travel venues, band are terrified. "The crew are sick and getting sicker. It's a period, let alone other cruises." matter of time before it gets to us and we're infected," she says. Why didn't Carnival simply dock every ship immediately "For some people, it will be the last trip of their lives." after their initial crises? "In effect, that's what people have As of early April, Carnival still had passengers at sea, nearly a been trying to do. But what happened was, ports close, airports month after the CDC issued a March & public advisory to "defer cose, borders close, and even now, we have tens of thousands all cruise ship travel worldwide." Spokesperson Frizzell says of crew on our ships that we can't get home," Donald