Question: How can you become an influential leader by using the techniques in Chapter 8? provide a lot of insightful information in your own words 252

How can you become an influential leader by using the techniques in Chapter 8? provide a lot of insightful information in your own words

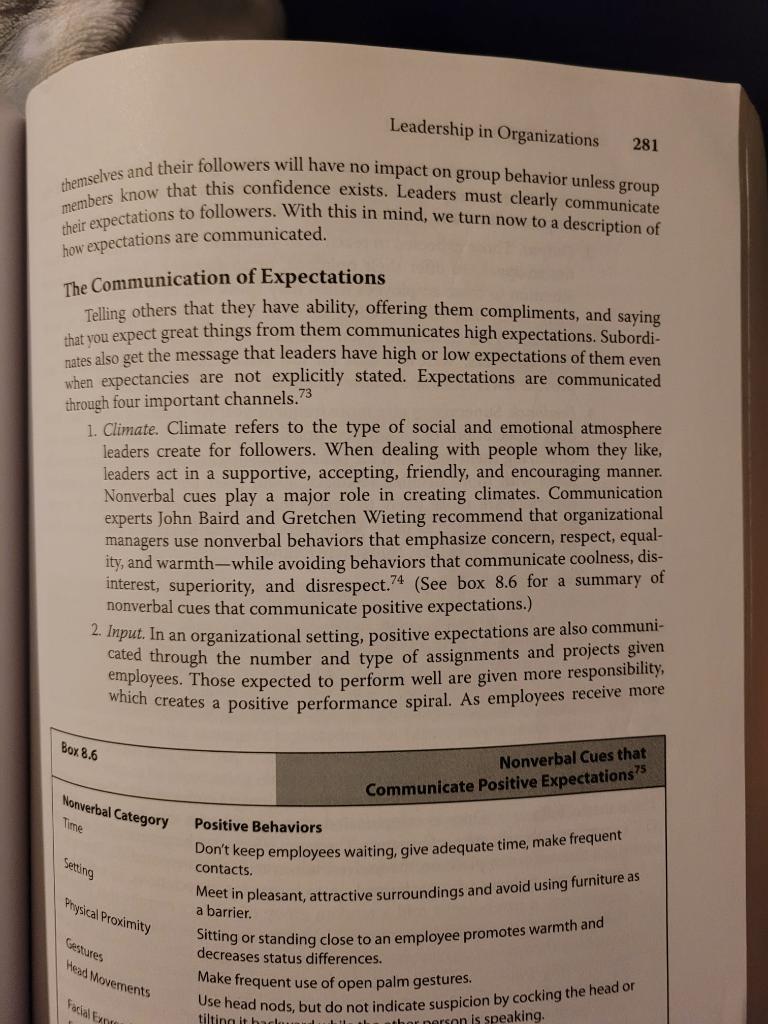

252 Chapter Eight Leaders and organizations: it's hard to talk for very long about either topie without mentioning the other. Although this chapter is devoted to a discussion of leaderchip in organizations, we've already talked at length about organizational leadership in this book. For example, many of the leadership theories presented in chapters 3 and 4 were developed by organization when you consider that leaders are extremely important to the health of organizations and that we spend a good deal of our time in organizations. Amitai Etzioni sums up the importance of organizations this way: We are born in organizations, educated by organizations, and most of us spend much of our lives working for organizations. We spend much of our leisure time paying, playing, and praying in organizations. Most of us will die in an organization and when the time comes for burial, the largest organization of all-the state-must grant official permission. 1 In the pages that follow we will focus, first of all, on the important communication tasks of leaders. Then we'll explore the ways that leader expectations can either increase or decrease follower performance. The Leader as Culture Maker Earlier we noted that humans have the ability to create reality through their use of symbols, and this is readily apparent in the organizational context. Organizations are formed through the process of communication. As organizational members meet and interact, they develop a shared meaning for events. Communication is not contained within the organization. Instead, communication i s the organization. Communication scholars and others have borrowed the idea of culture from the field of anthropology to describe how organizations create shared meanings. 2 From a cultural perspective, the organization resembles a tribe. Over time, the tribe develops its own language, hierarchy, ceremonies, customs, and beliefs. Because each organizational tribe shares different experiences and meanings, each develops its own unique way of seeing the world or culture. Anyone who joins a new company, governmental agency, or nonprofit group quickly recognizes unique differences in perspectives. New employees often undergo culture shock as they move into an organization with a different language, authority structure, and attitude toward work and people. Even long-term members can feel out of place if they change positions within the same organization. Each department or place if they change positions wistint subculture. Salespeople, for example, generally talk and dress differently than engineers employed by the same firm. 3 Elements of Organizational Culture Dividing organizational culture into three levels-assumptions, values, and symbols - provides important insights into how culture operates. Members of every organization share a set of assumptions that serve as the foundation for the group's Leadership in Organizations 253 culture. Assumptions are unstated beliefs about: human relationships (are relation. ships between organizational members hierarchical, group oriented, or individualistic?l; human nature (are humans basically good or evil or neither?); truth (is it rivealed by authority figures or discovered on one's own through testing?); the environment (shouid we master the environment, be subjugated to it, or live in harmony with it?); and universalism/particularism (should all organizational members be treated the same, or should some individuals receive preferential treatment?), 4 How an organization answers these questions will determine the way it treats employees and outsiders, whether or not members will respond favorably to directives from management, what sorts of products a company manufactures, and so on. Values make up the next level of organizational culture. Frequently (but not ahways) recognized and acknowledged by members, values reflect what the organization feels it "ought" to do. They serve as the yardstick for judging behavior. One way to identify important values is by examining credos, vision and mission statements, and advertising slogans. Words like "concern," "quality," and "corporate responsibility" articulate the official goals and standards of the organization. At times, however, the official or espoused values conflict with what people actually do, as in the case of an organization that touts its commitment to the environment but engages in illegal dumping. Symbols and symbolic creations called artifacts make up the top level of an organization's culture. By analyzing these visible elements, used in everyday interaction, we gain insights into an organization's assumptions and values. 5 Common organizational symbols and artifacts include: While there are far too many symbols to examine each in detail, experts pay particularly close attention to the first three symbols when they analyze organizational culture. We will review them briefly. A good way to determine how an organization views itself and the world is by listening carefully to the language that organizational members use. Word choices reflect and reinforce working relationships and values. The selection of the word "we" is revealing. It reflects a willingness to share power and credit and to work with others (see chapter 5). The choice of terms to describe followers also provides important insights into organizational life. For example, using the term "associates" rather than "employees" suggests that all organizational participants are important members of the team. Workers at Disney theme parks are called "cast members" to emphasize that they have significant roles to play in the overall performance for visitors who are, in turn, called "guests." Unfortunately, language also can reflect poor attitudes, as was the case at Goldman Sachs, where employees used the label "muppets" to refer to customers they thought were dumb or stupid. 254 Chapter Eight Language is a powerful motivator that focuses attention on some aspects of experience and directs it away from others. Those who speak of innovation or quality workmanship (BMW-The Ultimate Driving Machine") are generally more likely to provide creative and weell-crafted products. In addition, a common language binds group me the muently at school and on the job. Many verbal symbols like "student union" or "pull an all-nighter" that you take for granted as a student might not be familiar to those at your workplace. On the other hand, some of the tems you use at work might be new to other students. Organizational stories carry multiple messages. They reflect important values, inspire, describe what members should do, and provide a means to vent emotions. In many cases, organizational members are more likely to believe the stories they hear from coworkers than the statistics they hear from management. 6 For example, workers at Intel tell the story of a manager who was fired after receiving an average performance evaluation. She was dismissed because "there are no average employees at Intel. This story makes it clear that the company has high expectations of its members. (Tum back to chapter 1 for more information on types of stories and storytelling.) The key to effective leadership in corporations is reading and responding to cultural cues. - Terrence Deal Rituals, rites, and routines involve repeated patterns of behavior: saying "hello" in the morning to everyone on the floor; an annual staff retreat; or disciplinary procedures. Harrison Trice and Janice Beyer identify some common organizational rites: - Rites of passage. These events mark important changes in roles and statuses. When joining the army, for instance, the new recruit is stripped of his or her civilian identity and converted into a soldier with a new haircut, uniform, and prescribed ways of speaking and walking. - Rites of degradation. Some rituals are used to lower the status of organizational members, such as when a coach or top executive is fired. These events are characterized by degradation talk aimed at discrediting the poor performer. Critics may claim, for example, that the coach couldn't get along with the players or that the executive was overly demanding. - Rites of enhancement. Unlike rites of degradation, rites of enhancement raise the standing of organizational members. Giving medals to athletes and soldiers, listing faculty publications in the college newsletter, and publicly distributing sales bonuses are examples of such rituals. - Rites of renewal. These rituals strengthen the current system. Many widely used management techniques like management by objectives and organizational development are rites of renewanement by objectives and organiza Leadership in Organizations 255 Such programs direct attention toward employee evaluation, goal setting. long-range planning, and other areas that need improvemem, - Rites of conflict reduction. Organizations routinely use collective bargainitig. task forces, and committees to resolve conflicts. Even though committees may not make important changes, their formation may reduce tension since they signal that an organization is trying to be responsive. - Rites of integration. Rites of integration tie subgroups to the large system. Annual stockhoider meetings, professional gatherings, and office picnics all integrate people into larger organizations. - Rites of creation. These rites celebrate and encourage change, helping organizations remain flexible in turbulent environments marked by rapid shifts in markets and technology. Some groups rotate individuals in and out of the role of devil's advocate to challenge the status quo, for example. One company went so far as to appoint a "vice-president for revolutions." Every four years he made dramatic changes in the organization's structure and personnel in order to introduce new perspectives. - Rites of transition. Meetings, speeches, and other strategies can help organizational members accept changes that they didn't plan, as in the case of an unexpected merger. Addressing what the group has lost-past values, symbols, heroes - can ease the transition to a new culture. - Rites of parting. When organizations die (go bankrupt, disband), parting ceremonies are common. Members meet to reminisce and to say goodbye, often over meals. These events help participants understand and accept the loss and provide them with emotional support. Those who give voice and form to our search for meaning, and who help us make our world purposeful, are leaders we cherish, and to whom we return gift for gift. - Margaret Wheatley Shaping Culture Notable leaders concern themselves with much more than organizational charts, information management systems, and all the other traditional subjects of management training. They pay close attention to the assumptions, values, and symbols that ceete and reflect organizational culture. Organizational psychologist Edgar Schein bhhights the significant role that leaders play in the creation of organizational culture: Neither culture or leadership, when one examines each closely, can really be understood by itself. In fact, one could argue that the only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage culture and that the unique talent of leaders is their ability to create and manage culture and that the 8 258 Chapter Eight Your effectiveness as a leader will depend in large part on how well you put your "stamp" on an organization's culture or subcultures either as a founder or as a change agent. Perhaps you want to introduce more productive values and practices or encourage innovation as part of your vision or agenda. Cultural change, while neces. sary, is far from easy. Some organizational consultants seil programs that promise to modify organizational culture in a quick and orderly fashion. Such claims, which treat culture as yet another element housed in the organizational container, are misleading. Nothing is inevitable until it happens. -A. J. P. Taylor Change is difficult because cultures are organized around deeply rooted assumptions and values that affect every aspect of organizational life. Current symbols and goals provide organizational and individual stability, so any innovation can be threatening. Nonetheless, knowing how culture is embedded and transmitted can help you guide the cultural creation and change process. According to Edgar Schein, there are six primary and six secondary mechanisms you can use to establish and maintain culture. Primary mechanisms create the organization's "climate" and are the most important tools for shaping culture. Secondary mechanisms serve a supporting role, reinforcing messages sent through the primary mechanisms. 13 Primary Mechanisms 1. Attention. Systematically and persistently emphasize those values that undergird your organization's philosophy or plan. If your vision emphasizes customer service, for instance, then you need to focus the organization's attention on service activities. Your claim that service should be the company's first priority will not be taken seriously unless you as a leader perform service, honor good service, and penalize those who fail to respond to customer needs. In this way, others are encouraged to act as you do, to share your meaning that good service is important, and to believe service activities are critical. Some, like Ren McPherson of the Dana Corporation, argue that paying attention is the key activity of leader/managers. In McPherson's words: "When you assume the title of manager, you give up doing honest work for a living. You don't make it, you don't sell it, you don't service it What's left? Attention is all there is."14 Focused attention takes on even more importance when undertaking major transformation efforts. 2. Reactions to critical incidents. The way you respond to stressful events sends important messages about underlying organizational assumptions. Compare the way that organizations handle financial crises, for example. Some use layoffs as an efficient way to bandle financial crises, for example. Some ahead of efficiency, way to balance the books. Others, who put cooperaliat chapter 13 for more information on how to prepare for crisis situations.) Leadership in Organizations 259 ion spends its money is a key indicator of where it is headed. Looking at projected expenses reveals whether a company will invest in new product lines, for example. Further, the process of budgeting reveals a great deal about organizational values and assumptions. The greater the more likely it is to involve people from all levels of the organ, for ion in setting financial targets. Because budgeting sends such strong cultural signals, think carefully about what you want to communicate when deciding how to create the departmental or organizational spending plan. 4. Role modeling. Effective leaders work to develop others who share their vision. Become a coach and teacher to followers, particularly to those who are directly underneath you on the organizational ladder. Like The Container Store, you can also instill organizational philosophy through formal training programs. 5. Rewards. Rewards and punishments go hand in hand with the mechanism of attention described earlier. If service is your goal, then honor those who etc.) and discipline those who don't. events sends 6. Selection. Since organizations tend to perpetuate existing values and assumptions by hiring people who fit into the current system, reform the culture by recruiting members who share your new perspective rather than the old one. Promote those who support your vision; if necessary, help those who won't or can't change find employment at another organization. Chapter Fight - Measwrement. Assess individual and group knowledge-sharing behavior by measuring contributions (participation in online discussions, submissions to databases) and through cost-benefit analyses (reduced product development time, improved efficiency). Texas listruments estimates that it retained $1.5 billion in business by improving its delivery times through knowledge man- - Means. Facilitate knowledge sharing through technologies like e-mail, the Internet, groupware, and videoconferencing. - Ability. Help followers develop information-sharing skills (networking, relationship building) and tools for capturing knowledge (logs, computer programs). Support their attempts to reflect on and to record their learning as they perform on the job. - Motivation. Emphasize the intrinsic rewards of sharing data-saving time and money, completing a project, interacting with others, pride in being recognized as an expert. External rewards should not undermine team efforts or pit individuals against each other. Pay particular attention to the interpersonal dimension of information sharing by creating learning communities made up of groups of employees with similar tasks and interests. Demonstrate respect for the ideas of every follower. Power comes from transmitting information to make it productive, not hiding it. -Peter Drucker Building a Trusting Climate Trust, like learning, is essential to organizational success. Organizations with trusting climates are generally more productive, innovative, competitive, profitable, and effective. 25 Trust boosts collective performance by (1) fostering teamwork, cooperation, and risk taking; (2) increasing the flow and quality of information; and (3) improving problem solving. Those who work in a trusting environment are more productive because they have higher job satisfaction, enjoy better relationships, stay focused on their tasks, feel committed to the group, sacrifice for the greater organizational good, and are willing to go beyond their job descriptions to help out fellow employees. Organizational trust is defined as the collective level of positive expectations that members have about others and the group as a whole. Trusting cultures are marked by high expectatiout others and the group as a whole. Trusting cultures are marked cern for employees and (1) collective competence, (2) openness and honesty, (3)n27 Competence is belief in the eholders, (4) reliability, and (5) identification. organization. generation are convinced that the organization can survive throut mat 2 generating new products, meeting competitive pressures, and locating new mara Leadership in Organizations 267 Was the loss of trust reciprocal? If both parties feel betrayed, then it is likely that neither side will respond objectively. Avoid retaliation and start a con- Step 2. Determine the depth and brith roponse to each affected group. In the case of layoffs, loss of trust. Adjust your and departments will feel the impact more than others. More effort will need lons Step 3. Own up to the loss (don't ignore or downplay it). Acknowledge that trust has been broken as soon as possible. Promise to address the problem even if you dont have action steps in mind yet. Set a time when you will return with more spetics about how the issue will be addressed. trust may require providing more information, reconciling comperild trust. Rebuilding or reducing pay inequities. List the changes that need to occur to reach these obiects, tives. You may need to hold monthly informational meetings, merge work units, or form a compensation task force. Be careful not to overlook the details. Determing or the extent of your involvement in the changes, for example; decide who else will be engaged in the process; and set a timeline for implementation. Whatever matters to human beings, trust is the atmosphere in which it thrives. - Sissela Bok The Leader as Strategist Setting the overall direction of the enterprise is an important responsibility for many organizational leaders, whether small business owners, entrepreneurs, senior corporate officers, managers of business units, board members, or nonprofit executives. Setting the wrong direction is the cause of many organizational miscues. The Digital Equipment Company (DEC) was once the second-largest computer company in the world with over 100,000 employees. However, the company no longer exists after being sold to Compaq, which was purchased, in turn, by Hewlett-Packard. DEC leaders decided to make products that were only compatible with other DEC products and believed that superior engineering meant it didn't have to advertise products and believed that superior engineering meant it tors began offering similar When some of its products ran into trouble and competiees. IBM, offering similar items at lower prices, DEC was forced to lay off employfrom selling the other hand, remained successful because it made a strategic shift vices and computers and other hardware to providing software (technology serstrategic consulting). Netflix is another firm that has prospered through a series of Wider choices. At first it sent DVDs to customers through the mail, offering a Plans are nothing, planning is everything. 271 Dwight D. Eisenhower The analysis becomes the basis for the next stage in the planning process designing a strategy. Selecting a strategy typically involves trade-offs. One major trade-off is between cost and differentiation (being different). Attempts to differentiate products and services from those of competitors (by improving quality or offering luxury features, for instance) drives up costs. As a result, firms usually favor one approach over the other. 40 The strategy takes shape through a host of decisions made throughout the organization about, for example, product design, Implementation or execution is the final step in strategic plang. hould keep three questions in mind to make sure their strategy is glanners should 41 First, can we do it? The organization must have the resources is grounded in needs to do what it plans. Second, does it make sense? External threats outside the control of the organization should be carefully considered. Third, does anyone care? No strategy can succeed if audiences-buyers, clients of nonprofits-don't think that the plan is important. For example, some consumers only adopt new the latest cell phone or smart watch. If you don't know where you're going, you might end up somewhere else. -Casey Stengel The Leader as Sensemaker Strategic plans act as maps, identifying possible routes for the organization to follow as it travels forward. However, a number of scholars argue that leaders should navigate by a compass instead of a map. 42 Because the organizational envitonment is turbulent, they contend that leaders have to interpret conditions while on the go, making adjustments as events unfold. 43 Compasses are therefore more useful than maps because they provide leaders, like travelers, with a general sense of direction in the face of ambiguity. Leaders using compasses act as sensemakers, helping followers interpret or make sense of events and conditions. We believe that leaders need to engage in BOTH strategic planning and sensemaking, to be guided leaders need to engage in BOTH strategic planning and sensethought to be guided by both maps and compasses. Leaders must give careful ning can be the overall direction of their organizations since, as noted earlier, planmeeting obje key to success. Working toward fulfilling a mission and vision and Broup. Nevertives engages and energizes followers and channels the energy of the Intergroup Leadership Organizational success depends in large part on the coordinated efforts of groups and units. Doctors and nurses must work together to care for patients; faculty in different academic disciplines must coordinate their efforts to create new majors and programs; workers in newly merged manufacturing units must integrate their production lines and products. That makes intergroup leadership-promoting positive relations among subgroups-one of a leader's most important communication tasks. 52 Intergroup leadership is becoming even more critical as organizations become more team based. 53 In the past, coordinating group activities was the responsibility of top leaders. Now lower level leaders must coordinate patient care and curriculum decisions, redesign work processes, share information, gather resources, and so on. Intergroup leadership is as challenging as it is important. Often the units being asked to work together have previously been in competition with each other for money, staff, facilities, and other organizational resources. The groups may differ in status as well. Take the case of a business acquisition, for instance. Members of the newly acquired firm are at a significant disadvantage when compared to members of the parent company. They may feel alienated as the dominant group tries to impose its values on them. Group identities pose the biggest barrier to intergroup collaboration, however. 54 When asked to define ourselves, we typically refer to our group memberships, describing ourselves as communication majors, students, accountants, union members, or managers (see chapter 3). Such group identifications make it easy to favor our in-groups at the expense of out-groups. We excuse the behavior of our group members while condemning the same behavior by members of other groups. We are "assertive," for example, but they are "pushy." Further, we prefer leaders who put the interests of our group over those of outside groups. 55 Leaders who want to promote collaboration can start by encouraging interaction between units. Contact with outsiders can break down stereotypes and foster liking between individuals on different teams. Yet, contact by itself is not enough to guarantee that group members will develop positive feelings about their counterparts in other groups 56 Negative interaction, such as when one group threatens the existence of another group, reinforces stereotypes and generates further hostility. Try to set the groundwork for positive contacts by emphasizing that the groups need to work together to achieve a superordinate or shared objective like instituting a new change initiative. Emphasize important universal values like equality and respect for others. Provide opportunities for various teams to interact informally through or others. Provide opportunities for various Since differing group identities are the most significant obstacle to cooperation, the differing group identities are the most significant obstacle to cooperative intereader's primary task is creating an intergroup relational identity. that furchers encourage followers to see themselves as members of teams tity.59 function in relationship with other teams. Intergroup identity is the same time members recognize that they are part of a larger organization but, a sugroups. 278 Chapter Jight Successful intergroup leaders help create dual identities through their theto. ric. 50 They outline a shared vision and a collective identity for all units while coordination. They also note ho tinually emphasizing the importance of coordination. They also note how collaborating helps each group achicve its distinctive goals and retain its unique Theyes. bridge or span groups by having frequent contact with each team and ders, They bualiity relationships with individuals from every group. They are careful hol. to favor one group over the other. Ultimately, they come to embody intergroup relational identity because they are seen as leading both teams, not one group or the other. In so doing, they serve Coalitions of boundary-spanning leaders can be more effective than bound. ary-spanning leaders acting on their own. When members of one group see positive relations between team leaders, their attitude toward members of the other group improves as well. Combining leaders from low-and high-status units into the same coalition reduces the negative impacts of power differences by recogniz. members of the combined effort. Transference is an important outcome of successful intergroup leadership. When intergroup relational identities have been established, they are more likely to transfer to new relationships. For example, doctors who have established intergroup identities with current nurses will probably transfer these collaborative relationships to new nurses. Nurses who share collective identities with doctors tend to extend their collaborative efforts to hospital administrators and patients as well. Organizations are collections of interrelated groups more than collections of separate individuals. - Michael Hogg, Daan van Knippenberg, David Rast The Power of Expectations: The Pygmalion Effect What a leader expects is often what a leader gets. This makes the communication of expectations one of a leader's most powerful tools. Our tendency to live up to the expectations placed on us is called the Pygmalion effect. Prince Pygmalion (a figure in Greek mythology) created a statue of a beautiful woman whom he named Galatea. After the figure was complete, he fell in love with his creation. The goddess Venus took pity on the poor prince and brought Galatea to life. The Pygmalion effect has been studied in a number of settings. Consider the following examples of the power of expectations in action. - Patients often improve when they receive placebos because they believe the will get better. Leadership in Organizations 281 themselves and their followers will have no impact on group behavior unless group members know that this confidence exists. Leaders must clearly communicate their expectations to followers. With this in mind, we turn now to a description of The Communication of Expectations Telling others that they have ability, offering them compliments, and saying that you expect great things from them communicates high expectations. Subordinates also get the message that leaders have high or low expectations of them even when expectancies are not explicitly stated. Expectations are communicated through four important channels. 73 1. Climate. Climate refers to the type of social and emotional atmosphere leaders create for followers. When dealing with people whom they like, leaders act in a supportive, accepting, friendly, and encouraging manner. Nonverbal cues play a major role in creating climates. Communication experts John Baird and Gretchen Wieting recommend that organizational managers use nonverbal behaviors that emphasize concern, respect, equality, and warmth-while avoiding behaviors that communicate coolness, disinterest, superiority, and disrespect. 74 (See box 8.6 for a summary of nonverbal cues that communicate positive expectations.) 2. Input. In an organizational setting, positive expectations are also communicated through the number and type of assignments and projects given employees. Those expected to perform well are given more responsibility, which creates a positive performance spiral. As employees receive more 282 Chapter Fight tasks and complete them successfully, they gain self-confidence and the confidence of superiors. These star performers are then given additional responsibilities and are likely to meet the new chatienges as weil. 3. Output. Those expected to reach high standards are given more opportuni. ties to speak, to offer their opinions, or to disagree. Superiors pay more attention to these employees when they speak and offer more assistance to them when they need to come up with solutions. This is similar to what "ow achievers," wait less time for low achievers to answer questions, and provide fewer clues and follow-up questions to low achievers. 76 4. Feedback. Supervisors give more frequent positive feedback when they have high expectations of employees, praising them more often for success and criticizing them less often for failure. Managers also provide these subordinates with more detailed feedback about their performance. In contrast, superiors are more likely to praise minimal performance when it comes supervisors expect less from these followers. A leader's job is not to put greatness into people, but rather to recognize that it already exists, and to create an environment where that greatness can emerge and grow. -Brad Smith The Galatea Effect Our focus so far has been on the ways that leaders communicate their expectations to followers. Once communicated, these prophecies can have a significant impact on subordinate performance. The same effects can be generated by expectations that followers place on themselves, however. Earlier we noted the example of Israeli army trainees who performed up to instructor expectations. In a follow-up experiment, a psychologist told a random group of military recruits that they had high potential to succeed in a course. These trainees did as well as those who had been identified as high achievers to their instructors. In this case, the trainees became their own "prophets."77 The power of self-expectancies has been called the Galatea effect in honor of Galatea, the statue who came to life in the story of Pygmalion. Figure 8.1 depicts the relationship between supervisor and self-expectations. In the positive Pygmalion effect, the chain starts with the manager's expectations (box A), which causes him/her to allocate (arrow 1) more effective leadership behavior (box B). These leadership behaviors then positively influence (arrow 2) the expectations that followers have of themselves, particularly their sense of selfefficacy or personal power (box C). This increases motivation (arrow 3), leading to