Question: In this assignment you are expected to provide a brief overview of changes in health information systems in the United States since 2015. You post

In this assignment you are expected to provide a brief overview of changes in health information systems in the United States since 2015. You post should include:

- A discussion on interoperability

- A discussion on why health information systems are important in new payment models including MIPS and APMs.

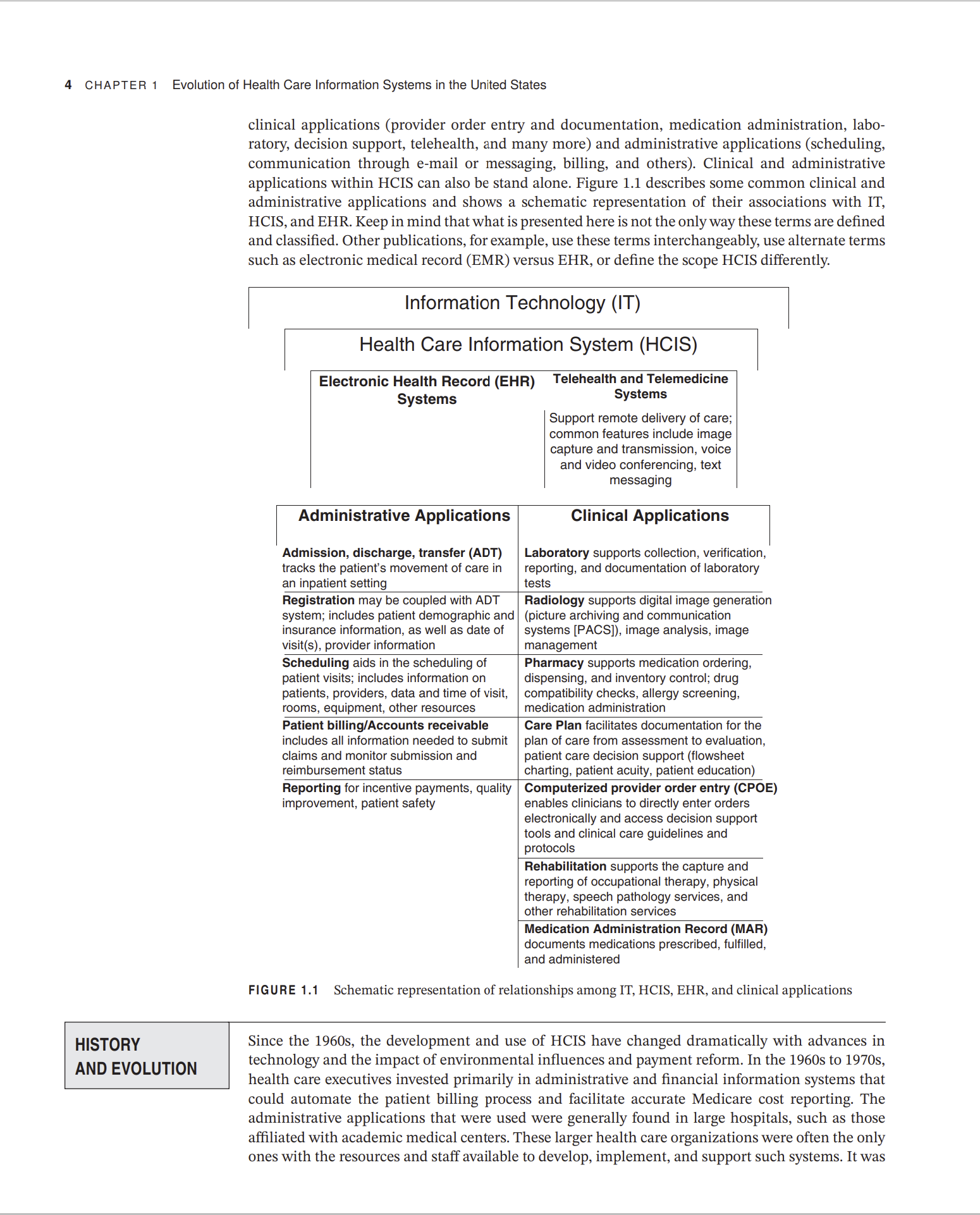

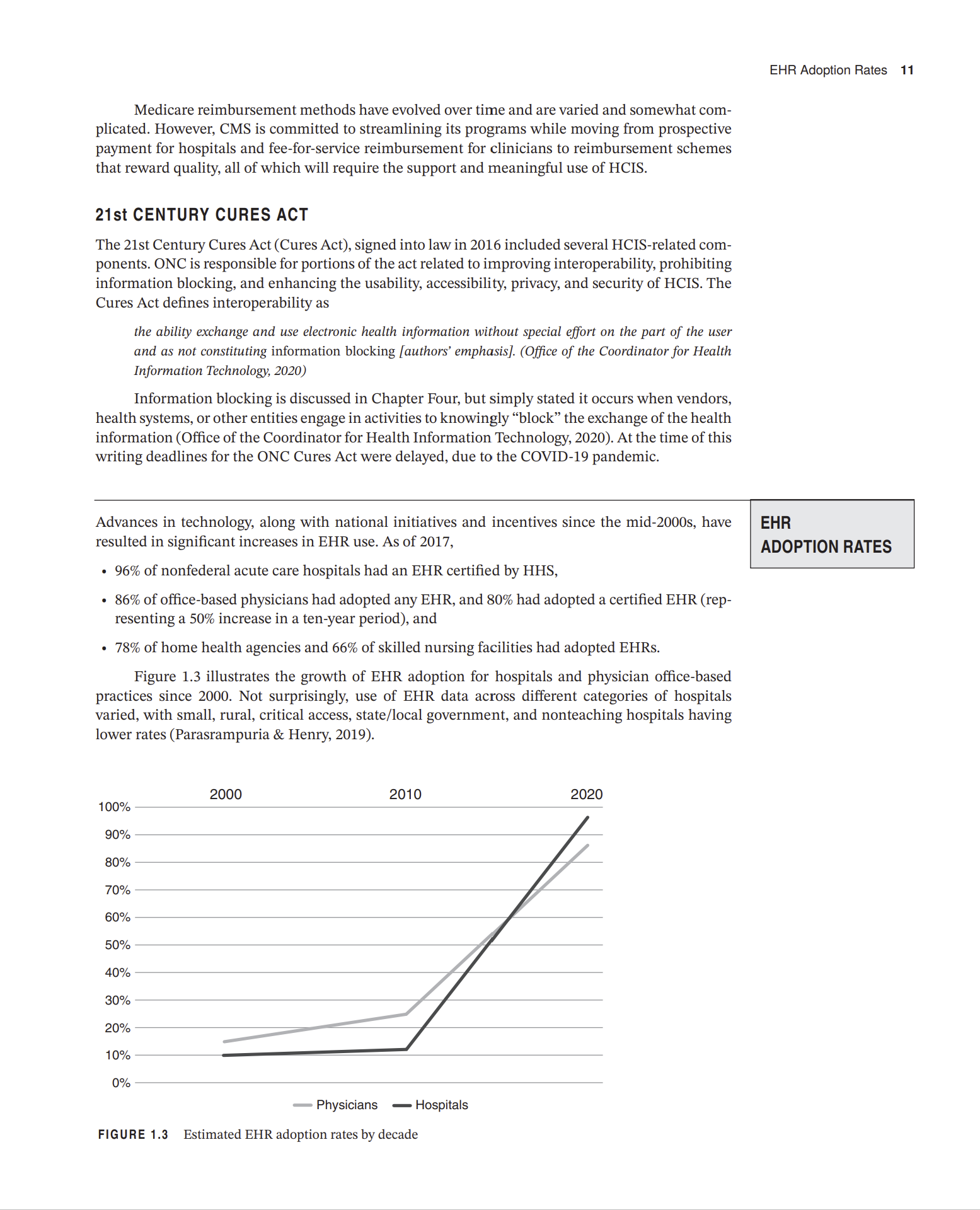

LEARNING OBJECTIVES - To define health care information systems and health information technology. - To be able to discuss some of the most significant influences shaping current and future health information technology in the United States. - To understand the roles national private sector and government initiatives have played in the advancement of health information technology in the United States. - To be able to describe major events since the 1990s that have influenced the adoption of health care information technologies and systems. oday's health care providers and organizations across the continuum of care have come to depend on reliable health care information systems (HCIS) to manage their patient populations effectively while reducing costs and improving the quality of care. This chapter will explore some of the most significant influences shaping current and future HCIS in the United States. Certainly, advances in information technology affect HCIS development, but national private sector and government initiatives have played key roles in the adoption and application of the technologies in health care. Information technology (IT) is a broad term describing the combination of computer and electronic device hardware and software, local and internet network infrastructures, and data, including images, videos, and voice, across all industries. An information system (IS) is an arrangement of data, processes, people, and information technology that interact to collect, process, store, and provide as output the information needed to support the organization (Whitten \& Bentley, 2007). Note that IT is a component of every information system, but the term IT includes technologies within and outside of an organization. From an organizational perspective, computer applications are components of information systems that are needed to support specific processes. Throughout this textbook, IT is the preferred term for technologies that support health care information systems. The technologies, however, are not exclusive to health care. The term health IT (HIT) is often used in literature and other publications to describe IT when it is deployed in a health care environment. A health care information system (HCIS) includes the processes, people, and information technology that come together to provide health or health-related information to support the health care organization. Within health care organizations, computer applications are necessary to support both clinical and administration processes. Central to HCIS in hospitals and most physician office-based practices is an electronic health record (EHR) system that integrates clinical applications (provider order entry and documentation, medication administration, laboratory, decision support, telehealth, and many more) and administrative applications (scheduling, communication through e-mail or messaging, billing, and others). Clinical and administrative applications within HCIS can also be stand alone. Figure 1.1 describes some common clinical and administrative applications and shows a schematic representation of their associations with IT, HCIS, and EHR. Keep in mind that what is presented here is not the only way these terms are defined and classified. Other publications, for example, use these terms interchangeably, use alternate terms FIGUkE 1.1 Scnematc representation or relatonsnps among 11,HClD, EHK, ana cincal applications Since the 1960s, the development and use of HCIS have changed dramatically with advances in technology and the impact of environmental influences and payment reform. In the 1960s to 1970s, health care executives invested primarily in administrative and financial information systems that could automate the patient billing process and facilitate accurate Medicare cost reporting. The administrative applications that were used were generally found in large hospitals, such as those affiliated with academic medical centers. These larger health care organizations were often the only ones with the resources and staff available to develop, implement, and support such systems. It was clinical applications (provider order entry and documentation, medication administration, laboratory, decision support, telehealth, and many more) and administrative applications (scheduling, communication through e-mail or messaging, billing, and others). Clinical and administrative applications within HCIS can also be stand alone. Figure 1.1 describes some common clinical and administrative applications and shows a schematic representation of their associations with IT, HCIS, and EHR. Keep in mind that what is presented here is not the only way these terms are defined and classified. Other publications, for example, use these terms interchangeably, use alternate terms FIGUkE 1.1 Scnematc representation or relatonsnps among 11,HClD, EHK, ana cincal applications Since the 1960s, the development and use of HCIS have changed dramatically with advances in technology and the impact of environmental influences and payment reform. In the 1960s to 1970s, health care executives invested primarily in administrative and financial information systems that could automate the patient billing process and facilitate accurate Medicare cost reporting. The administrative applications that were used were generally found in large hospitals, such as those affiliated with academic medical centers. These larger health care organizations were often the only ones with the resources and staff available to develop, implement, and support such systems. It was HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT Five years after the IOM report advocating CPRs was published, President Clinton signed into law the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996 (which is discussed in detail in Chapter Twelve). HIPAA was designed primarily to make health insurance more affordable and accessible, but it included important provisions to simplify administrative processes and to protect the security and confidentiality of personal health information. HIPAA was part of a larger health care reform effort and a federal interest in HCIS for purposes beyond reimbursement. HIPAA also brought national attention to the issues surrounding the use of personal health information in electronic form. The Internet had revolutionized the way that consumers, providers, and health care organizations accessed health information, communicated with each other, and conducted business, creating new risks to patient privacy and security. IOM PATIENT SAFETY REPORTS A second IOM report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System (Kohn, Corrigan, \& Donaldson, 2000), brought national attention to research estimating that 44,000 to 98,000 patients die each year because of medical errors. A subsequent related report by the IOM Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety, Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care (Aspden, 2004), called for health care organizations to adopt information technology capable of collecting and sharing essential health information on patients and their care. This IOM committee examined the status of standards, including standards for health data interchange, terminologies, and medical knowledge representation. Here is an example of the committee's conclusions: - As concerns about patient safety have grown, the health care sector has looked to other industries that have confronted similar challenges, in particular, the airline industry. This industry learned long ago that information and clear communications are critical to the safe navigation of an airplane. To perform their jobs well and guide their plane safely to its destination, pilots must communicate with the airport controller concerning their destination and current circumstances (e.g., mechanical or other problems), their flight plan, and environmental factors (e.g., weather conditions) that could necessitate a change in course. Information must also pass seamlessly from one controller to another to ensure a safe and smooth journey for planes flying long distances, provide notification of airport delays or closures because of weather conditions, and enable rapid alert and response to extenuating circumstance, such as a terrorist attack. - Information is as critical to the provision of safe health care-which is free of errors of commission and omission-as it is to the safe operation of aircraft. To develop a treatment plan, a doctor must have access to complete patient information (e.g., diagnoses, medications, current test results, and available social supports) and to the most current science base (Aspden, 2004). Whereas To Err Is Human focused primarily on errors that occur in hospitals, the 2004 Patient Safety report examined the incidence of serious safety issues in other settings as well, including ambulatory care facilities and nursing homes. Its authors point out that earlier research on patient safety focused on errors of commission, such as prescribing a medication that has a potentially fatal interaction with another medication the patient is taking, and they argue that errors of omission are equally important. An example of an error of omission is failing to prescribe a medication from which the patient would likely have benefited (Institute of Medicine, Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety, 2003). A significant contributing factor to the unacceptably high rate of medical errors reported in these two reports and many others is poor information management practices. Illegible prescriptions, unconfirmed verbal orders, unanswered telephone calls, and lost medical records could all place patients at risk. TRANSPARENCY AND PATIENT SAFETY The federal government also responded to quality-of-care concerns by promoting health care transparency (for example, making quality and price information available to consumers) and furthering the adoption of HCIS. In 2003, the Medicare Modernization Act was passed, which expanded the program to include prescription drugs and mandated the use of electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) among health plans providing prescription drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries. A year later (2004), President Bush called for the widespread adoption of EHR systems within the decade to improve efficiency, reduce medical errors, and improve quality of care. By 2006, he had issued an executive order directing federal agencies that administer or sponsor health insurance programs to make information about prices paid to health care providers for procedures and information on the quality of services provided by physicians, hospitals, and other health care providers publicly available. This executive order also encouraged adoption of HIT standards to facilitate the rapid exchange of health information (The White House, 2006). During this period significant changes in reimbursement practices also materialized in an effort to address patient safety, health care quality, and cost concerns. Historically, health care providers and organizations had been paid for services rendered regardless of patient quality or outcome. Nearing the end of the decade, payment reform became a hot item. For example, pay for performance (P4P) or value-based purchasing pilot programs became more widespread. P4P reimbursed providers based on meeting predefined quality measures and thus was intended to promote and reward quality. The Centers for Medicare \& Medicaid Services (CMS) notified hospitals and physicians that future increases in payment would be linked to improvements in clinical performance. Medicare also announced it would no longer pay hospitals for the costs of treating certain conditions that could reasonably have been prevented-such as bedsores, injuries caused by falls, and infections resulting from the prolonged use of catheters in blood vessels or the bladder-or for treating "serious preventable" events-such as leaving a sponge or other object in a patient during surgery or providing the patient with incompatible blood or blood products. Private health plans followed Medicare's lead and began denying payment for such mishaps. Providers began to recognize the importance of adopting improved HCIS to collect and transmit the data needed under these payment reforms. OFFICE OF THE NATIONAL COORDINATOR FOR HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY In April 2004, President Bush signed Executive Order No. 13335, 3 C.F.R., establishing the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and charged the office with providing "leadership for the development and nationwide implementation of an interoperable health information technology infrastructure to improve the quality and efficiency of health care." In 2009, the role of the ONC (organizationally located within the US Department of Health and Human Services) was strengthened when the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act legislatively mandated it to provide leadership and oversight of the national efforts to support the adoption of EHRs and health information exchange (HIE) (ONC,2015). In spite of the various national initiatives and changes to reimbursement during the first decade of the twenty-first century, by the end of it only 25 percent of physician practices (Hsiao, Hing, Socey, \& Cai, 2011) and 12 percent of hospitals (Jha, 2010) had implemented "basic" EHR systems. The far majority of solo and small physician practices continued to use paper based medical record systems. Studies show that the relatively low adoption rates among solo and small physician practices were because of cost and the misalignment of incentives (Jha et al., 2009). Patients, payers, and purchasers had the most to gain from physician use of EHR systems, yet it was the physician 8 CHAPTER 1 Evolution of Health Care Information Systems in the United States who was expected to bear the total cost. The HITECH Act was passed as a part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009 to address this misalignment of incentives, to provide health care organizations and providers with some funding for the adoption and Meaningful Use of EHRs, and to promote a national agenda for HIE. 2010-2015: HEALTH CARE REFORM AND THE GROWTH OF HCIS HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY FOR ECONOMIC AND CLINICAL HEALTH ACT Two major objectives of HITECH were to strengthen protections for electronic health information and to leverage IT to improve patient care. HITECH addresses electronic health information privacy and security concerns through several provisions that strengthen the civil and criminal enforcement of HIPAA rules, which will be explored further in Chapter Twelve. Additional components of HITECH promote the use of IT to improve the quality of care. HITECH established the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentive Programs. Eligible professionals and hospitals that adopted, implemented, or upgraded to a certified EHR meeting established "meaningful use" criteria received incentive payments. Examples of meaningful use criteria were requirements for incorporating electronic prescribing (e-prescribing) and capturing a problem list. Current meaningful use criteria are outlined in Chapter Two. Through the Medicare EHR Incentive Program, each eligible professional who adopted and achieved meaningful EHR use in 2011 or 2012 earned up to $44,000 over a five-year period; eligible hospitals earned over $2 million. The Medicaid EHR Incentive Program paid up to $63,500 for each eligible professional and over $2 million to each eligible hospital. 2014 was the last year for eligible hospital and provider EHR adopters to begin their participation in the initial rounds of Medicare EHR Incentive Programs. The Medicaid Incentive Program enrollment ended in 2016. Over the life of initial EHR Incentive Programs, Medicare alone paid over $15 billion in incentive payments (CMS, 2021). EHR certification administered by ONC was implemented in three stages beginning in 2011 (see Figure 1.2): - Stage 1 set the foundation by establishing requirements for the electronic capture of clinical data, including providing patients with electronic copies of health information. - Stage 2 expanded upon the Stage 1 criteria with a focus on advancing clinical processes and ensuring that the meaningful use of EHRs supported the aims and priorities of the National Quality Strategy. Stage 2 criteria encouraged the use of certified electronic health record technologies for continuous quality improvement at the point of care and the exchange of information in the most structured format possible. - In October 2015, CMS released a final rule that established Stage 3 for 2017 and beyond, which focuses on using certified electronic health record technologies to improve health outcomes. Many small physician practices and rural hospitals did not have the in-house expertise to select, implement, and support EHR systems to meet certification standards. To address these needs, HITECH funded sixty-two regional extension centers (RECs) throughout the nation to support providers in adopting and becoming meaningful users of EHRs. The RECs are primarily intended to provide advice and technical assistance to primary care providers, especially those in small practices, and to small rural hospitals, which often do not have IT expertise. HITECH also provided state grants to help build health information exchange (HIE) infrastructures for exchange of electronic health information among providers and between providers and consumers. In early 2010 the ONC granted $548 million to fifty-six states through the State Health Information Exchange Cooperative Agreement Program (ONC, n.d.). FIGUKE 1.2 Stages of LMS EHK incentive programs AFFORDABLE CARE ACT In addition to the increased efforts to promote HCIS through legislated programs, the early 2010s brought dramatic change to the health care sector as a whole with the passage of significant health care reform legislation. Americans have grappled for decades with some type of "health care reform" in an attempt to achieve the simultaneous "triple aims" for the US health care delivery system (these aims and related quality programs are discussed in greater detail in Chapter Three): - Improve the patient experience of care - Improve the health of populations - Reduce per capita cost of health care (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], n.d.) Full achievement of these aims has been challenging within a health care delivery system managed by different stakeholders-payers, providers, and patients-whose goals are frequently not well aligned. A major attempt at reform occurred in 2010, when President Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), now known as the Affordable Care Act(ACA). In addition to the better-known regulations to require and improve access to health insurance, the ACA included numerous changes to the Medicare program, including continued reductions in Medicare payments to certain hospitals for hospital-acquired conditions and excessive preventable hospital readmissions. Additionally, CMS established an innovation center to test, evaluate, and expand different payment structures and methodologies to reduce program expenditures while maintaining or improving quality of care. Through the innovation center and other means, CMS has been aggressively pursuing implementation of value-based payment methods and exploring the viability of alternative models of care and payment. The various ACA programs rely heavily on quality HCIS to achieve their goals. A greater emphasis than ever is placed on facilitating patient engagement in their own care through the use of technology. New models of care and payment include improved health for populations as an explicit goal, requiring HCIS to manage the sheer volume and complexity of data needed. PROMOTING INTEROPERABILITY PROGRAM Under the original CMS Meaningful Use program, hospitals and eligible professionals were able to qualify for substantial payments from EHR Incentive Programs if they adopted and used EHRs according to the program's established "meaningful use" criteria. In 2018, The Meaningful Use program became known as Promoting Interoperability as its purpose evolved from adoption of EHRs to promoting interoperability among EHRs. Currently, Promoting Interoperability and certified EHRs are key components of CMS Quality Payment Programs, which are discussed in more detail in Chapter Three. ONC continues to oversee the certification process using The 2015 Edition Health IT Certification Criteria (2015 Edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) Certification Criteria, 2016). MEDICARE ACCESS AND CHIP REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2015 The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) streamlined existing CMS value-based payment models under the Quality Payment Program (QPP) umbrella. There are two QPP tracks from which providers under Medicare Part B can choose: 1. The Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) 2. Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs) 2015-PRESENT: PROMOTING INTEROPERABILITY, PATIENT ENGAGEMENT AND POPULATION HEALTH n of Health Care Information Systems in the United States Traditional MIPS requires participating clinicians to report a variety of measures and activities in order to determine Medicare reimbursement. The measures are divided into four groups: 1. Quality (six or more measures selected from a pool of measures) 2. Promoting Interoperability (based on EHR certification criteria) 3. Cost measures 4. Improvement activities (two to four approved activities) Participants subsequently receive negative or positive payment adjustments based on how well they perform on these measures. Participants, however, have expressed that the reporting requirements are burdensome and not always relevant or helpful to their practices. Consequently, CMS introduced MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs), providing a new MIPS reporting framework beginning in 2021, designed to lessen clinicians' reporting burden, make performance measurement more meaningful, and encourage participation in APMs. CMS's goal is to refine the pathways over the next five years. Participants' data reporting will be decreased by CMS using existing administrative claims data. In addition, quality and improvement measures will be targeted to the clinician's area of practice. Table 1.1 provides an example of how MVPs will impact a surgeon (CMS, 2020). Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs) evolved from, modified, and added to established Medicare value-based payment programs. There are multiple models of APMs, including primary care medical homes (PCMHs) and accountable care organizations (ACOs). The PCMH emphasizes the central role of primary care and care coordination, with the vision that every person should have the opportunity to easily access high-quality primary care in a place that is familiar and knowledgeable about their health care needs and choices. A PCMH is not a location, but rather a patient-centered model of care. ACOs emphasize the urgent need to think beyond patients to populations, providing a vision for increased accountability for performance and spending across the health care system (Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, 2011). Both models rely on health care organizations and physicians providing coordinated and integrated care in an evidence-based, cost-effective way. 1 Population Health Measures: a set of administrative claims-based quality measures that focus on public health priorities and/ or cross-cutting population health issues; CMS provides the data through administrative claims measures, for example, the AllCause Hospital Readmission measure. 2 Enhanced Performance Feedback: CMS provides data and feedback that is meaningful to clinicians and patients. Source: Based on Centers for Medicare \& Medicaid Services (2020). EHR Adoption Rates 11 Medicare reimbursement methods have evolved over time and are varied and somewhat complicated. However, CMS is committed to streamlining its programs while moving from prospective payment for hospitals and fee-for-service reimbursement for clinicians to reimbursement schemes that reward quality, all of which will require the support and meaningful use of HCIS. 21st CENTURY CURES ACT The 21st Century Cures Act (Cures Act), signed into law in 2016 included several HCIS-related components. ONC is responsible for portions of the act related to improving interoperability, prohibiting information blocking, and enhancing the usability, accessibility, privacy, and security of HCIS. The Cures Act defines interoperability as the ability exchange and use electronic health information without special effort on the part of the user and as not constituting information blocking [authors' emphasis]. (Office of the Coordinator for Health Information Technology, 2020) Information blocking is discussed in Chapter Four, but simply stated it occurs when vendors, health systems, or other entities engage in activities to knowingly "block" the exchange of the health information (Office of the Coordinator for Health Information Technology, 2020). At the time of this writing deadlines for the ONC Cures Act were delayed, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in technology, along with national initiatives and incentives since the mid-2000s, have resulted in significant increases in EHR use. As of 2017, - 96% of nonfederal acute care hospitals had an EHR certified by HHS, - 86% of office-based physicians had adopted any EHR, and 80\% had adopted a certified EHR (representing a 50% increase in a ten-year period), and - 78% of home health agencies and 66% of skilled nursing facilities had adopted EHRs. Figure 1.3 illustrates the growth of EHR adoption for hospitals and physician office-based practices since 2000. Not surprisingly, use of EHR data across different categories of hospitals varied, with small, rural, critical access, state/local government, and nonteaching hospitals having lower rates (Parasrampuria \& Henry, 2019). EHR ADOPTION RATES FIGURE 1.3 Estimated EHR adoption rates by decade 12 CHAPTER 1 Evolution of Health Care Information Systems in the United States SUMMARY Chapter One provides a chronology of the some of the most significant national drivers in the development, growth, and use of HCIS in the United States. Since the 1990s and the publication of The Computer-Based Patient Record: An Essential Technology for Health Care, the national HIT landscape has certainly evolved, and it will continue to do so. Although widespread adoption of EHRs has been achieved for the most part, challenges to realizing a truly integrated interoperable national infrastructure are numerous-but the need for one has never been greater. Recognizing that the technology is not the major barrier to the national infrastructure, the government, through legislation, CMS Quality Payment Programs, the ONC, and other initiatives, will continue to play a significant role in the "meaningful use" and increased interoperability of HCIS, pushing for the alignment of incentives within the health care delivery system. In a 2016 speech, CMS acting Chief Andy Slavitt summed up the government's role in achieving its vision with the following statements: The focus will move away from rewarding providers for the use of technology and towards the outcome they achieve with their patients. Second, providers will be able to customize their goals so tech companies can build around the individual practice needs, not the needs of the government. Technology must be user-centered and support physicians, not distract them. Third, one way to aid this is by leveling the technology playing field for start-ups and new entrants ... We are deadly serious about interoperability. We will begin initiatives . . pointing technology to fill critical use cases like closing referral loops and engaging a patient in their care. Technology companies that look for ways to practice "data blocking" in opposition to new regulations will find that it won't be tolerated. (Nerney, 2016) Much of what is discussed in Chapter One will be explored more fully in subsequent chapters of this book. The purpose of Chapter One is to provide a snapshot of the factors that have shaped and are shaping current HCIS in the United States and enough historical background to set the stage for why health care managers and leaders must understand and actively engage in the implementation of effective systems to achieve better health for individuals and populations while managing costs

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts