Question: Please discuss the management, core and support processes for a fastfood restaurant (i.e. a landscape model). If you have any questions, please let me know.

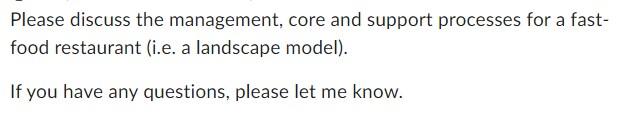

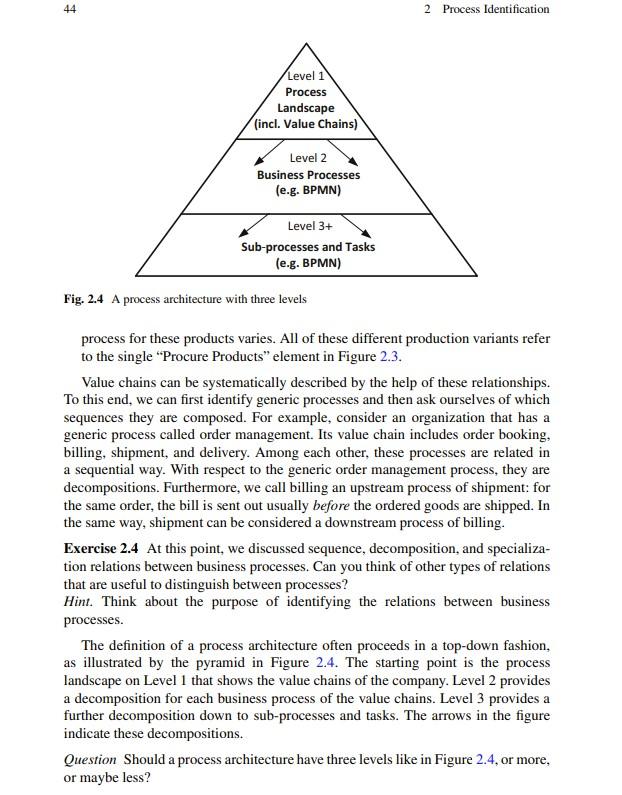

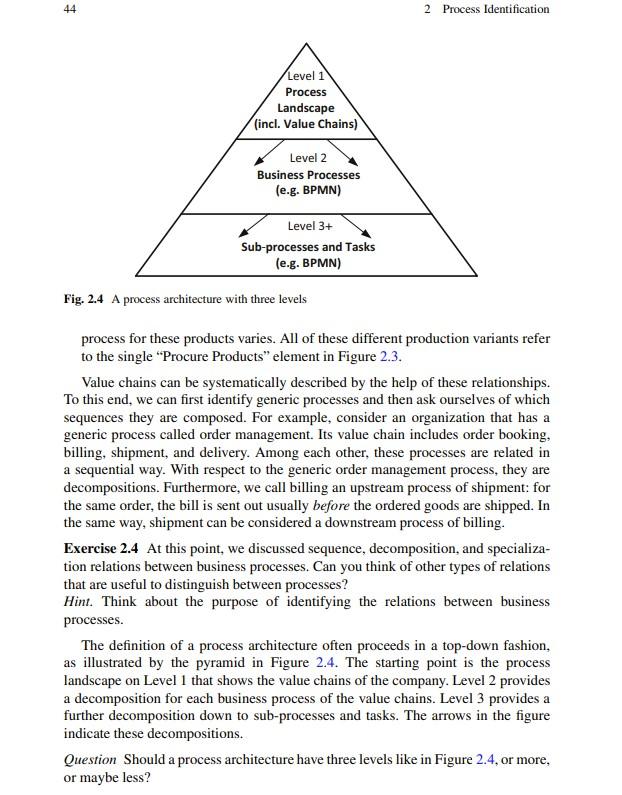

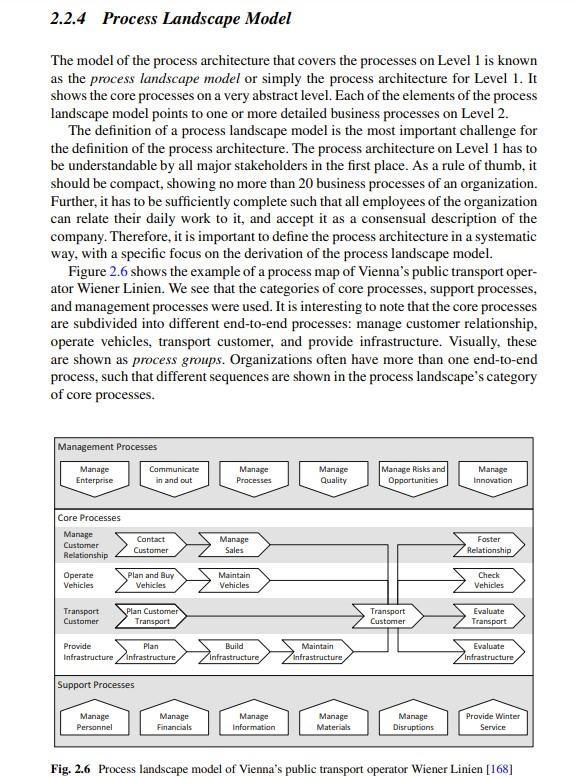

Please discuss the management, core and support processes for a fastfood restaurant (i.e. a landscape model). If you have any questions, please let me know. Fig. 2.4 A process architecture with three levels process for these products varies. All of these different production variants refer to the single "Procure Products" element in Figure 2.3. Value chains can be systematically described by the help of these relationships. To this end, we can first identify generic processes and then ask ourselves of which sequences they are composed. For example, consider an organization that has a generic process called order management. Its value chain includes order booking, billing, shipment, and delivery. Among each other, these processes are related in a sequential way. With respect to the generic order management process, they are decompositions. Furthermore, we call billing an upstream process of shipment: for the same order, the bill is sent out usually before the ordered goods are shipped. In the same way, shipment can be considered a downstream process of billing. Exercise 2.4 At this point, we discussed sequence, decomposition, and specialization relations between business processes. Can you think of other types of relations that are useful to distinguish between processes? Hint. Think about the purpose of identifying the relations between business processes. The definition of a process architecture often proceeds in a top-down fashion, as illustrated by the pyramid in Figure 2.4. The starting point is the process landscape on Level 1 that shows the value chains of the company. Level 2 provides a decomposition for each business process of the value chains. Level 3 provides a further decomposition down to sub-processes and tasks. The arrows in the figure indicate these decompositions. Question Should a process architecture have three levels like in Figure 2.4, or more, or maybe less? 2.2.4 Process Landscape Model The model of the process architecture that covers the processes on Level 1 is known as the process landscape model or simply the process architecture for Level 1. It shows the core processes on a very abstract level. Each of the elements of the process landscape model points to one or more detailed business processes on Level 2. The definition of a process landscape model is the most important challenge for the definition of the process architecture. The process architecture on Level 1 has to be understandable by all major stakeholders in the first place. As a rule of thumb, it should be compact, showing no more than 20 business processes of an organization. Further, it has to be sufficiently complete such that all employees of the organization can relate their daily work to it, and accept it as a consensual description of the company. Therefore, it is important to define the process architecture in a systematic way, with a specific focus on the derivation of the process landscape model. Figure 2.6 shows the example of a process map of Vienna's public transport operator Wiener Linien. We see that the categories of core processes, support processes, and management processes were used. It is interesting to note that the core processes are subdivided into different end-to-end processes: manage customer relationship, operate vehicles, transport customer, and provide infrastructure. Visually, these are shown as process groups. Organizations often have more than one end-to-end process, such that different sequences are shown in the process landscape's category of core processes. The definition of a process landscape model requires the involvement of major stakeholders of the organization, either using interviews or, preferably, using a workshop setting. The contributions of the stakeholders are required in order to establish the legitimacy of the resulting model. For this reason, it is important that all senior executives are involved. Once the commitment of the stakeholders is secured, there are several steps that help us to define the process landscape model in a systematic way. We present these steps as a sequence, but note that in practice there will be jumps back and forth with iterations. 1. Clarify terminology: The key terms to be used in the process landscape model should be defined. Often, there exists already an organizational glossary, which can be used as a reference. Reference models are also useful to support this step. The definition helps to make sure that all stakeholders have a consistent understanding of the process landscape model to be defined. 2. Identify end-to-end processes: End-to-end processes are those processes that interface with customers and suppliers of the organization. The goods and services that an organization provides to customers or procures from suppliers are a good starting point for this identification, since they are explicitly defined in most organizations. Several properties help us to distinguish end-to-end processes, including: - Product type: This property identifies types of products that are produced in a similar way. For instance, at this abstract level, an automotive company might distinguish cars from trucks. - Service type: This property identifies types of services that are produced in a similar way. For instance, a software vendor might distinguish purchased software from software-as-a-service. - Channel: this property represents the channels through which the organization interacts with its customers. For example, an insurance company might separate its Internet offerings from its offerings via intermediary banks. - Customer type: This property represents the types of customer that the organization deals with. A bank might, for instance, distinguish wealth customers, private banking customers, and retail customers. The identification of end-to-end processes combines an external view of what the provisions of the organization are from the view of the customer, and an internal view of how these are created. The selection of the listed properties should be driven by the idea to only define separate end-to-end processes when their internal behavior is substantially different. Those end-to-end processes that are shown on the process landscape model represent the value chains of the organization. 3. For each end-to-end process, identify its sequential processes: For this step, it is important to identify the internal, intermediate outcomes of an end-to-end process. There are different perspectives that help setting the boundaries of these processes: - Product lifecycle: The lifecycle of a product or service includes different states, which can be used to subdivide an end-to-end process. For instance, a plant construction company typically first submits a quote, then sets up the contract, designs the plant in collaboration with the customer, produces its building blocks, delivers and constructs the plant on premise, writes the invoice, and provides maintenance services. - Customer relationship: There are also typical stages that a customer relationship goes through. First, leads are generated, then a contract is sealed and services provided. For these, invoices are written. The contract might be changed and eventually terminated. - Supply chain: Along the supply chain, materials are procured, which are used to produce products. These are checked for quality assurance and delivered to customers. - Transaction stages: There are different stages that transactions typically go through from initiation to negotiation, execution, and acceptance. Consider, for instance, buying clothes at a fashion retailer. First, interest in the products is generated (initiation). Advisory services in the shop have to be provided to the customers, such that they can make a good decision (negotiation). Taking the clothes to the point of sale marks execution. The payment completes the transaction (acceptance). - Change of business objects: If there are different business objects, the process should be split up into respective business processes. For instance, the transition from a quote to a contract or from an order to a payment mark the boundaries of different processes. A change of multiplicity is a specific condition for splitting up; for example, when several job applications lead to one hiring. - Separation: Different stages of a process can also be defined by a temporal, spatial, logical, or other type of separation. Often, these separations define handoffs, and major handoffs are suitable points to distinguish sequential processes. The identification of business processes is closely connected with the internal view of an end-to-end process. It is also referred to as the identification of internal functions, because there typically exist functional units in the organization like divisions or departments that are responsible for particular business processes. 4. For each business process, identify its major management and support processes: The question for this step is what is required in order to execute the previously identified processes. Typical support processes, as also shown in Figure 2.6, are management of personnel, financials, information, and materials. Note, however, that these support processes can be core processes if they are an integral part of the business model. For a staff-borrowing company, personnel management is a core process. However, management processes are usually generic. 2.2 Definition of the Process Architecture 51 5. Decompose and specialize business processes: Each of the business processes of the process landscape should be further subdivided into an abstract process on Level 2 of the process architecture. Also further subdivision to Level 3 might be appropriate until processes are identified that can be managed autonomously by a single process owner. There are different considerations when this subdivision should stop: - Manageability: The smaller the number of the identified processes, the bigger their individual scope is. In other words, if only a small number of processes is identified, then each of these will cover numerous operations. This makes their management more difficult. Among others, the involvement of a large number of staff in a single process will make communication more difficult and improvement projects more complex. - Impact: A subdivision into only a few large processes will increase the impact of their management. The more operations are considered to be part of a process, the easier it will become, for example, to spot opportunities for efficiency gains by rooting out redundant work. Also risks arising from compliance violations might be considered as having an impact. 6. Compile process profile: Each of the identified processes should not only be modeled, but also described using a process profile. This process profile supports the definition of the boundaries of the process, its vision and process performance indicators, its resources, and its process owner. Figure 2.7 shows an example of a process profile of BuildIT's procure-to-pay process. 7. Check completeness and consistency: These checks should build on the following inputs. First, reference models can be used to check whether all major processes that are relevant for the organization are included. Reference models can also help us to check the consistency of the terminology. Second, it should be checked whether all processes can be associated with functional units of the organization chart and the other way around