Question: Please label and bold or underline course concepts A) Read the article What monetary rewards can and cannot do: How to show employees the money

Please label and bold or underline course concepts

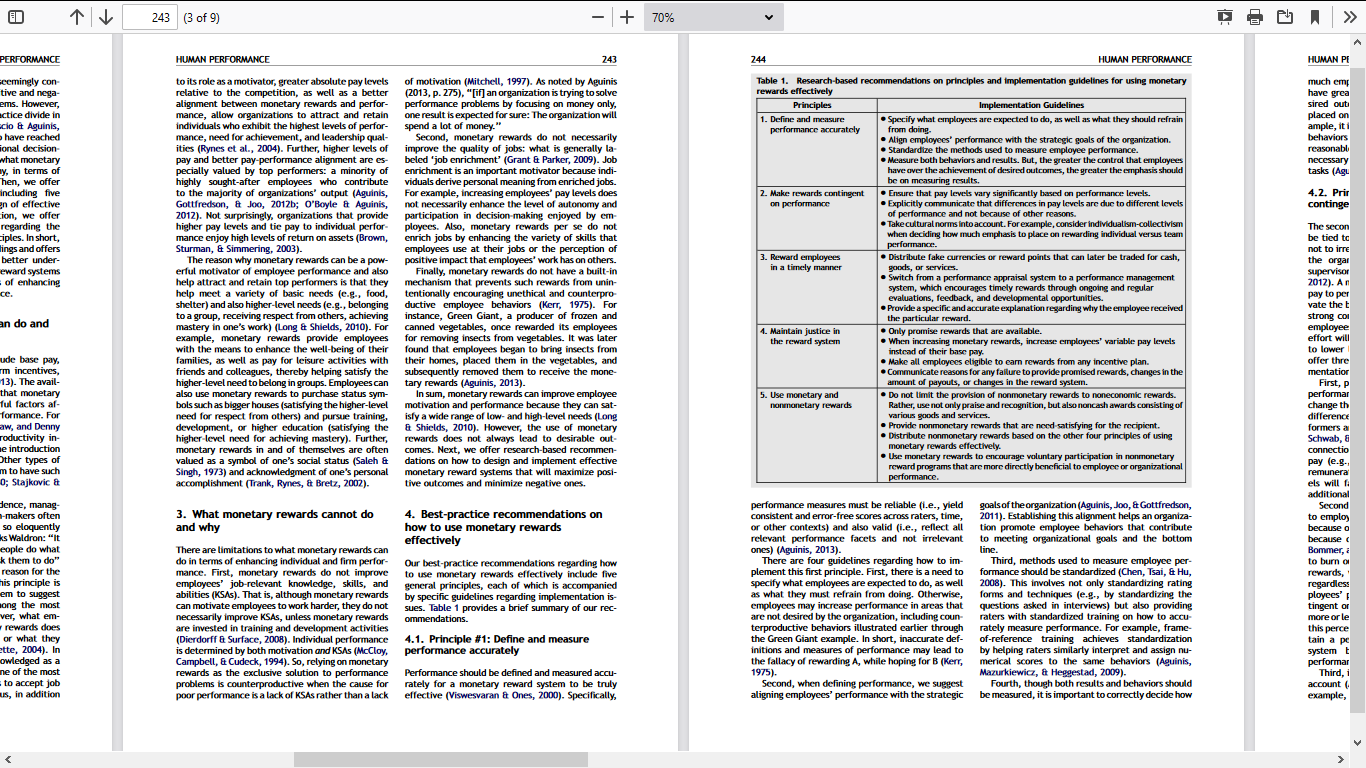

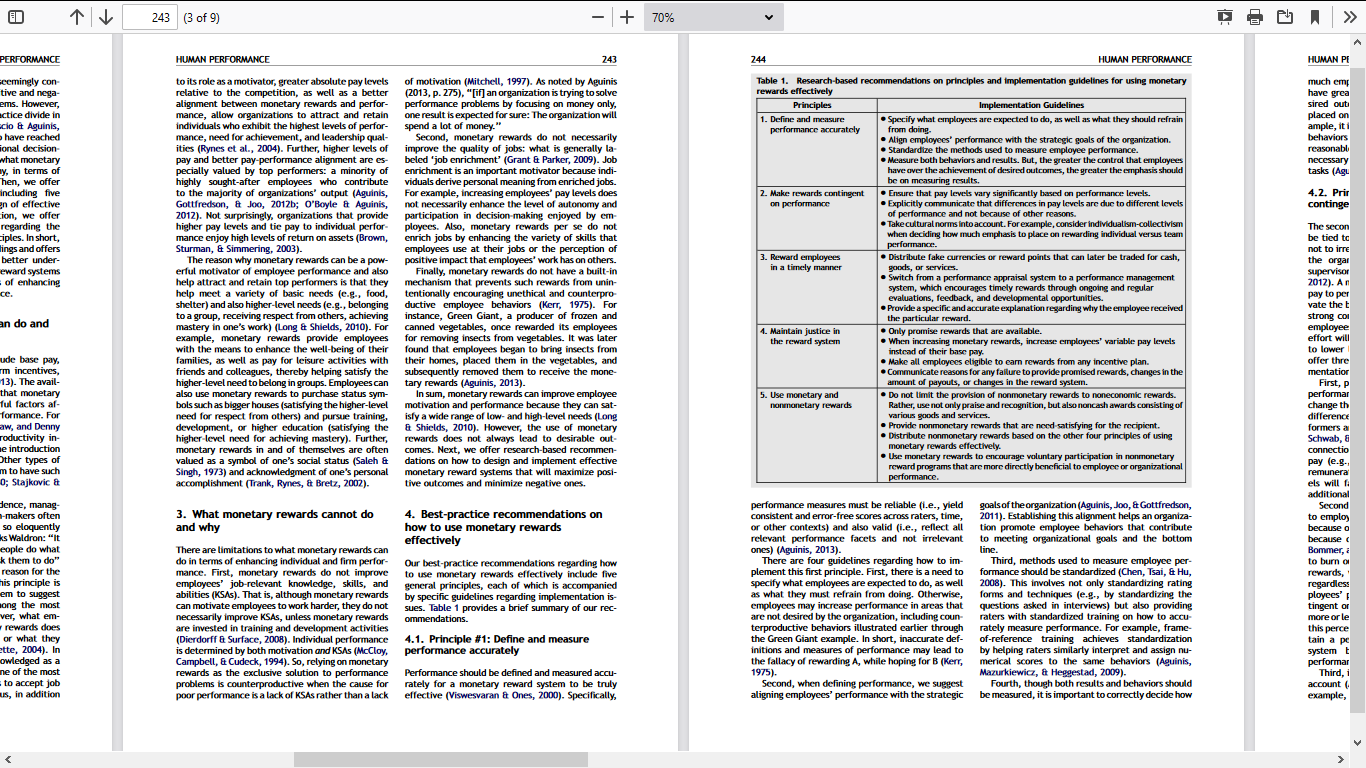

A) Read the article What monetary rewards can and cannot do: How to show employees the money by Aguinis, Joo & Gottfredson. It is located in the module. Refer to Table 1: Research-based recommendations on principles and implementation guidelines for using monetary rewards effectively.

B) Provide an pay practice example (positive or negative) highlighting one or more of these principles - ideally from your work experience but can be from what you are familiar with through a friend, family member or current event).

C) Apply evidence-based management - what made this pay practice particularly effective or ineffective? Consider how or why these pay practices were used, think about the groups or individuals doing the work, type of work, and environment the work is done. What recommendations do you have for improvement and what information or research would you need in order make those decisions?

1 241 (1 of 9) - + 70% >> Business Horizons (2013) 56, 741 749 242 HUMAN PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE Available online at www.sciencedirect.com SciVerse ScienceDirect KELLEY SCHOOL OF BUSINESS INDIANA UNIVERSITY www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor ELSEVIER HUMAN PERFORMANCE What monetary rewards can and cannot do: How to show employees the money Herman Aguinis*, Harry Joo, Ryan K. Gottfredson Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 1309 E Tenth Street, Bloomington, IN 47405-1701, U.S.A. to its role as a motivator, greater absol relative to the competition, as wel alignment between monetary reward mance, allow organizations to attra individuals who exhibit the highest le mance, need for achievement, and le ities (Rynes et al., 2004). Further, hi pay and better pay-performance alig pecially valued by top performers: highly sought-after employees wh to the majority of organizations' ou Gottfredson, & Joo, 2012b; O'Boy! 2012). Not surprisingly, organizations higher pay levels and tie pay to indi mance enjoy high levels of return on Sturman, & Simmering, 2003). The reason why monetary rewards erful motivator of employee perform help attract and retain top performe help meet a variety of basic need: shelter) and also higher-level needs (e to a group, receiving respect from oth mastery in one's work) (Long & Shiel example, monetary rewards provic with the means to enhance the well- families, as well as pay for leisure a friends and colleagues, thereby helpi higher-level need to belong in groups. I also use monetary rewards to purcha: bols such as bigger houses (satisfying th need for respect from others) and pe development, or higher education ( higher level need for achieving mast monetary rewards in and of themsel valued as a symbol of one's social st Singh, 1973) and acknowledgment of accomplishment (Trank, Rynes, & Brel ; KEYWORDS Motivation; Compisation; Human resource management; Individual performance; Employee retention Rod: Yeah! Louder! systems that allows us to reconcile seemingly con tradictory conclusions about the positive and nega Jerry: Show me the money!! tive effects of monetary reward systems. However, given the much lamented science-practice divide in Rod: I need to feel you, Jerry! management and related fields (Cascio & Aguinis, 2008), this research does not seem to have reached Jerry: (Screaming) Show me the money!!! Show me many managers and other organizational decision- the money!!! makers. Accordingly, next we discuss what monetary rewards can and cannot do, and why, in terms of Rod: Congratulations, Jerry, you are still my agent. improving employee performance. Then, we offer research-based recommendations including five As was the case for Rod Tidwell, monetary rewards general principles to guide the design of effective can be a very powerful motivator, and the effect that monetary reward systems. In addition, we offer monetary rewards have on motivation often trans specific research-based guidelines regarding the lates into other positive outcomes such as employee implementation of each of these principles. In short, retention (Jewell & Jewell, 1987). Moreover, our article distills research-based findings and offers Stajkovic and Luthans (2001) conducted a study in recommendations that allow for a better under- cluding more than 7,000 employees with identical job standing of when and why monetary reward systems responsibilities and found that objective perfor are likely to be successful in terms of enhancing mance improvements measured in real-time by a employee motivation and performance. meter in each employee's work station-were high- est among employees in a monetary incentive inter- vention program compared to those who received 2. What monetary rewards can do and social recognition or performance feedback instead. why In addition, benefits of monetary rewards seem to be global and have been documented not only in the Examples of monetary rewards include base pay, United States but also in many other countries and cost-of-living adjustments, short-term incentives, industries around the world including China (Du & and long-term incentives (Aguinis, 2013). The avail- Choi, 2010), Australia (Cadsby, Song, & Tapon, 2007), able empirical evidence documents that monetary and England (Campbell, Reeves, Kontopantelis, rewards are among the most powerful factors af- Sibbald, &t Roland, 2009). fecting employee motivation and performance. For However, monetary rewards do not always lead to example, Locke, Feren, McCaleb, Shaw, and Denny desirable outcomes. First, generous amounts of (1980) found that an employee's productivity in monetary incentives sometimes fail to motivate creased by an average of 30% after the introduction (Beer & Cannon, 2004) and may even lead to coun of individual monetary incentives. Other types of terproductive outcomes such as financial misrepre rewards and interventions do not seem to have such sentation activities (Harris & Bromiley, 2007). a powerful effect (Locke et al., 1980; Stajkovic & Second, when promised very high amounts of mon Luthans, 2001). etary incentives, employees can 'choke,' or suffer In spite of the research-based evidence, manag- declined performance levels as a result of sharply ers and other organizational decision-makers often increased fear of failure (Chib, De Martino, Shimojo, seem to lose sight of the principle so eloquently & O'Doherty, 2012). Third, employees can develop a encapsulated by former Avon CEO Hicks Waldron: "it sense of entitlement to certain amounts of payouts took me a long while to learn that people do what (Beer & Cannon, 2004) and, as a result, actual you pay them to do, not what you ask them to do payouts that fall short of their expectations can (Cascio ft Cappelli, 2009). One likely reason for the cause various negative reactions such as pay-level lack of generalized acceptance of this principle is dissatisfaction and intentions to quit the organiza that results of employee surveys seem to suggest tion (Schaubroeck, Shaw, Duffy, & Mitra, 2008). that monetary rewards are not among the most This point is humorously illustrated in National important motivating factors. However, what em- Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (Chechik, 1989), in ployees say is the value of monetary rewards does which the main character Clark Griswold (played by not always reflect what they think or what they Chevy Chase) goes on a bizarre rant in front of his actually do (Rynes, Gerhart, & Minette, 2004). In family after finding out that his usually generous fact, although pay is not often acknowledged as a Christmas cash bonus was not given out for the year. critical factor in most surveys, it is one of the most There is an important body of scholarly research important factors leading employees to accept job on motivation, individual performance, and reward offers (Feldman et Amold, 1978). Thus, in addition Abstract Monetary rewards can be a very powerful determinant of employee motivation and performance which, in turn, can lead to important returns in terms of firm-level performance. However, monetary rewards do not always lead to these desirable outcomes. We discuss in this installation of Human Performance what monetary rewards can and cannot do, and reasons why, in terms of improving employee performance. Also, we offer research-based recommendations including the following five general principles to guide the design of successful monetary reward systems: (1) define and measure performance accurately, (2) make rewards contin- gent on performance, (3) reward employees in a timely manner, (4) maintain justice in the reward system, and (5) use monetary and nonmonetary rewards. In addition, we offer specific research-based guidelines for implementing each of the five principles. In short, our article summarizes research-based findings and offers recommendations that will allow managers and other organizational decision makers to understand when and why monetary reward systems are likely to be successful in terms of enhancing employee motivation and performance. 2012 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Show me the money Jerry: What can I do for you, Rod? You just tell me. What can I do for you? A well-known scene from the movie Jerry Maguire (Crowe, 1996) portrays the high value that employ- Rod: It's a very personal, a very important thing. ees give to monetary rewards. The scene involves Are you ready, Jerry? the following shortened telephone conversation be- tween Jerry Maguire, a sports agent played by Tom Jerry: I'm ready Cruise, and Rod Tidwell, a National Football League wide receiver played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.: Rod: Here it is: Show me the money. Oh-ho-ho! Show! Me! The! Money! A-ha-ha! Jerry, doesn't it make you feel good just to say that? Say it with me one time, Jerry! Corresponding author E-mail address: haguinis indiana.edu (H. Aguinis) Jerry: Show me the money! : 0007-6813/$ se front matter 2012 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor 2012.11.007 3. What monetary rewards ca and why There are limitations to what monetar do in terms of enhancing individual ar mance. First, monetary rewards do employees' job-relevant knowledge abilities (KSAs). That is, although mon can motivate employees to work harde necessarily improve KSAs, unless mon are invested in training and developn (Dierdorff & Surface, 2008). Individual is determined by both motivation and Campbell, & Cudeck, 1994). So, relyin rewards as the exclusive solution to problems is counterproductive when poor performance is a lack of KSAs ratt 11 - + 70% >> HUMAN PE much em have grea sired out placed on ample, iti behaviors reasonabl necessary tasks (Agi 4.2. Prir continge and 243 (3 of 9) PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE 243 244 HUMAN PERFORMANCE eemingly con to its role as a motivator, greater absolute pay levels of motivation (Mitchell, 1997). As noted by Aguinis Table 1. Research-based recommendations on principles and implementation guidelines for using monetary tive and nega relative to the competition, as well as a better (2013, p. 275). "[if an organization is trying to solve rewards effectively ems. However, alignment between monetary rewards and perfor performance problems by focusing on money only, Principles Implementation Guidelines actice divide in mance, allow organizations to attract and retain one result is expected for sure: The organization will 1. Define and measure ecio e Aguinis, individuals who exhibit the highest levels of perfor- Specify what employees are expected to do, as well as what they should refrain spend a lot of money." performance accurately from doing. have reached mance, need for achievement, and leadership qual Second, monetary rewards do not necessarily Align employees' performance with the strategic goals of the organtzation. Tonal decision ities (Rynes et al., 2004). Further, higher levels of improve the quality of jobs: what is generally la Standardize the methods used to measure employee performance. vhat monetary pay and better pay-performance alignment are es beled 'job enrichment' (Grant & Parker, 2009). Job Measure both behaviors and results. But, the greater the control that employees my, in terms of pecially valued by top performers: a minority of enrichment is an important motivator because indi- have over the achievement of desired outcomes, the greater the emphasis should Then, we offer highly sought-after employees who contribute viduals derive personal meaning from enriched jobs. be on measuring results. including five to the majority of organizations' output (Aguinis, For example, increasing employees' pay levels does 2. Make rewards contingent Ensure that pay levels vary significantly based on performance levels. en of effective Gottfredson, & Joo, 2012b; O'Boyle at Aguinis, not necessarily enhance the level of autonomy and on performance Explicitly communicate that differences in pay levels are due to different levels Lion, we offer 2012). Not surprisingly, organizations that provide participation in decision-making enjoyed by em- of performance and not because of other reasons. regarding the higher pay levels and tie pay to individual perfor ployees. Also, monetary rewards per se do not Take cultural norms into account. For example, consider individualism-collectivism iples. In short, mance enjoy high levels of return on assets (Brown, enrich jobs by enhancing the variety of skills that when deciding how much emphasis to place on rewarding individual versus team lings and offers performance. Sturman, & Simmering, 2003). employees use at their jobs or the perception of better under The reason why monetary rewards can be a pow positive impact that employees' work has on others. 3. Reward employees Distribute fake currencies or reward points that can later be traded for cash, eward systems erful motivator of employee performance and also Finally, monetary rewards do not have a built-in in a timely manner goods, or services. of enhancing help attract and retain top performers is that they mechanism that prevents such rewards from unin- Switch from a performance appraisal system to a performance management system, which encourages timely rewards through ongoing and regular help meet a variety of basic needs (e.g., food, tentionally encouraging unethical and counterpro evaluations, feedback, and developmental opportunities. shelter) and also higher-level needs (e.g., belonging ductive employee behaviors (Kerr, 1975). For Provide a specific and accurate explanation regarding why the employee received to a group, receiving respect from others, achieving instance, Green Giant, a producer of frozen and the particular reward. an do and mastery in one's work) (Long & Shields, 2010). For canned vegetables, once rewarded its employees 4. Maintain justice in Only promise rewards that are available. example, monetary rewards provide employees for removing insects from vegetables. It was later with the means to enhance the well-being of their When increasing monetary rewards, increase employees' variable pay levels the reward system found that employees began to bring insects from instead of their base pay. ude base pay. families, as well as pay for leisure activities with their homes, placed them in the vegetables, and Make all employees eligible to earn rewards from any incentive plan. . rm incentives, friends and colleagues, thereby helping satisfy the subsequently removed them to receive the mone- Communicate reasons for any failure to provide promised rewards, changes in the 13). The avail- higher-level need to belong in groups. Employees can tary rewards (Aguinis, 2013). amount of payouts, or changes in the reward system. that monetary also use monetary rewards to purchase status sym In sum, monetary rewards can improve employee 5. Use monetary and Do not limit the provision of nonmonetary rewards to noneconomic rewards. ful factors al- bols such as bigger houses (satisfying the higher-level motivation and performance because they can sat- nonmonetary rewards Rather, use not only praise and recognition, but also noncash awards consisting of formance. For need for respect from others) and pursue training, isfy a wide range of low- and high-level needs (Long various goods services. saw, and Denny development, or higher education (satisfying the & Shields, 2010). However, the use of monetary Provide nonmonetary rewards that are need satisfying for the recipient. roductivity in higher level need for achieving mastery). Further, rewards does not always lead to desirable out- Distribute nonmonetary rewards based on the other four principles of using ne introduction monetary rewards in and of themselves are often comes. Next, we offer research-based recommen- monetary rewards effectively. Other types of valued as a symbol of one's social status (Saleh & dations on how to design and implement effective Use monetary rewards to encourage voluntary participation in nonmonetary m to have such Singh, 1973) and acknowledgment of one's personal monetary reward systems that will maximize posi- reward programs that are more directly beneficial to employee or organizational performance 0; Stajkovic & accomplishment (Trank, Rynes, & Bretz, 2002). tive outcomes and minimize negative ones. dence, manag performance measures must be reliable (.e., yield goals of the organization (Aguinis, Joo, & Gottfredson, -makers often 3. What monetary rewards cannot do 4. Best-practice recommendations on consistent and error-free scores across raters, time, 2011). Establishing this alignment helps an organiza- so eloquently and why how to use monetary rewards or other contexts) and also valid (i.e., reflect all tion promote employee behaviors that contribute ks Waldron: "It effectively relevant performance facets and not irrelevant to meeting organizational goals and the bottom eople do what There are limitations to what monetary rewards can ones) (Aguinis, 2013). line. k them to do" do in terms of enhancing individual and firm perfor There are four guidelines regarding how to im- Our best-practice recommendations regarding how Third, methods used to measure employee per- reason for the mance. First, monetary rewards do not improve to use monetary rewards effectively include five plement this first principle. First, there is a need to formance should be standardized (Chen, Tsai, & Hu, mis principle is employees' job-relevant knowledge, skills, and general principles, each of which is accompanied specify what employees are expected to do, as well 2008). This involves not only standardizing rating em to suggest abilities (KSAs). That is, although monetary rewards by specific guidelines regarding implementation is- as what they must refrain from doing. Otherwise, forms and techniques (e.g., by standardizing the song the most can motivate employees to work harder, they do not sues. Table 1 provides a brief summary of our rec- employees may increase performance in areas that questions asked in interviews) but also providing ver, what em- necessarily improve KSAs, unless monetary rewards ommendations. are not desired by the organization, including coun raters with standardized training on how to accu rewards does are invested in training and development activities terproductive behaviors illustrated earlier through rately measure performance. For example, frame- or what they (Dierdorff & Surface, 2008). Individual performance 4.1. Principle #1: Define and measure the Green Giant example. In short, inaccurate def of-reference training achieves standardization ette, 2004). In is determined by both motivation and KSAS (McCloy. performance accurately initions and measures of performance may lead to by helping raters similarly interpret and assign nu- owledged as a Campbell, & Cudeck, 1994). So, relying on monetary the fallacy of rewarding A, while hoping for B (Kerr, merical scores to the same behaviors (Aguinis, ne of the most rewards as the exclusive solution to performance Performance should be defined and measured accu- 1975). Mazurkiewicz, & Heggestad, 2009). to accept job problems is counterproductive when the cause for rately for a monetary reward system to be truly Second, when defining performance, we suggest Fourth, though both results and behaviors should us, in addition poor performance is a lack of KSAs rather than a lack effective (Visweswaran at Ones, 2000). Specifically, aligning employees' performance with the strategic be measured, it is important to correctly decide how The secon be tied to not to irre the orgai supervisor 2012). An pay to per vate the t strong col employee effort will to lower offer thre mentatior First, P performar change th difference formers a Schwab, & connectio pay (e.g. remunera els will: additional Second to employ because o because Bommer, to burn of rewards, regardless ployees' tingent or more or le this perce tain a pe systemt performar Third, i account example, 1 245 (5 of 9) - + 70% IUMAN PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE 245 246 HUMAN PERFORMANCE HU es for using monetary at they should refrain f the organtzation. Tormance. ontrol that employees er the emphasis should much emphasis to place on each. When employees have greater control over the achievement of de sired outcomes, then more emphasis should be placed on measuring results (Grote, 1996). For ex- ample, it is better to emphasize the measurement of behaviors for employees who have not yet had a reasonable period of time on the job to develop the necessary knowledge and skills to complete their tasks (Aguinis, 2013). 4.2. Principle #2: Make rewards contingent on performance an (e. cei th me pe bu ski dis for by nance levels. due to different levels vidualism-collectivism individual versus team 'individualism-collectivism. In general, people in countries such as the United States and Australia, which are more individualistic, place great value on individual achievement. Alternatively, people in countries such as China and Guatemala, which are more collectivistic, place great value on group identification. Accordingly, employees in individu alistic countries tend to prioritize their own individ- ual interests above the interests of groups in which they belong (e.g., extended family). On the other hand, employees in collectivistic societies tend to value interdependence and place the interests of the groups they are affiliated with above their own. Thus, monetary reward systems that emphasize individual rewards will be more successful in more individualistic compared to more collectivistic soci- eties. For example, the average U.S. worker, and more so for high-performing employees, prefers pay systems that are strongly contingent on individual performance (Trank et al., 2002). On the other hand, the greater an organization's collectivist na- ture (e.g., an organization located in a collectivist country), the greater the emphasis should be on rewarding team performance in addition to reward- ing individual performance (Aguinis et al., 2012c). 4.3. Principle #3: Reward employees in a timely manner no cal be traded for cash, nance management ng and regular that rewards everyone who reaches beyond the expected" (https://www.firstdatabravo.com/). Supervisors are able to distribute Bravo! points to their employees on the spot based on performance; points can then be redeemed for gift cards, electron- ics, home accessories, sporting goods, and travel options. Second, we suggest that organizations switch from a performance appraisal system to a perfor- mance management system (Aguinis et al., 2011). Performance appraisal systems usually involve a formal, end-of-the-year performance evaluation form that managers unfortunately often fill out carelessly because it is a requirement from the human resource department, and employees typi- cally receive no ongoing feedback and developmen- tal opportunities (Aguinis et al., 2011). In contrast, a performance management system involves ongoing and regular evaluation, feedback, and developmen- tal opportunities (Aguinis, 2013). When an organi- zation has a performance management rather than a performance appraisal system, the regular interac- tions centered on evaluating and developing perfor- mance will provide useful information so that employees will be able to receive rewards in a timely manner. Third, we suggest that managers provide a spe- cific and accurate explanation regarding why an employee is being rewarded. For example, avoid making vague statements such as good job" and instead provide explanations such as, "Our monthly figures show that of all the tellers during the month of April, you conducted the most transactions" (Aguinis, Gottfredson, & Joo, 2012, p. 109). Em- ployees are more likely to repeat desired behaviors if they have a specific and accurate understanding of why they received a reward (Aguinis, 2013). 4.4. Principle #4: Maintain justice in the reward system he employee received the people who maintain the reward system provide personal treatment and information in a just man- ner?") (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). Next, we offer four implementation guidelines regarding this fourth principle. First, to maintain distributive justice, it is impor- tant to only make promises of rewards that are actually available (Aguinis, 2013). Otherwise, unful- filled promises tend to incite negative emotions and counterproductive behaviors (Bordia, Restubog, & Tang, 2008). Second, to maintain procedural justice, when increasing monetary rewards, it is better to increase employees' variable pay rather than their base pay (Aguinis, 2013). The reason for this recommendation is that employees typically see variable pay as more contingent on performance and thus less stable over time (Kuhn & Yockey, 2003). Therefore, if the amount of compensation received from variable pay, as opposed to base pay, fluctuates (e.g., de- clines) due to changes in performance levels, an employee is more likely to accept the fact than feel injustice. Third, also related to procedural justice, orga- nizations should make all of their employees eligible to earn payment from any incentive plan, instead of only a select group of individuals (Aguinis, 2013). For example, if the top executives of a company are promised stock options and profit-sharing depending on their performance, extending this to lower-level employees fosters the perception that they are in a just workplace. In turn, this perception increases the motivation levels of all employees in the orga nization (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). Fourth, to maintain interactional justice, it is important to provide a thorough and convincing explanation for any circumstances such as budget constraints or organization-wide pay cuts that make it no longer feasible to keep promises of rewards that were previously available (Greenberg, 1990). Even when no explicit promises are made, employ- ees tend to form expectations, such that a thorough and convincing explanation is also warranted when changes are made to actual amounts of payouts or the system (Schaubroeck et al., 2008). ic res bu be th rel tar aw tia ati tit au WC tai variable pay levels centive plan ewards, changes in the neconomic rewards. wh awards consisting of The second principle is that monetary rewards must be tied to performance as closely as possible, and not to irrelevant factors such as number of years in the organization or unquestionably following a supervisor's directives (Trevor, Reilly, & Gerhart, 2012). A monetary reward system that closely links pay to performance helps attract, retain, and moti- vate the best, while sorting out the rest. Without a strong connection between pay and performance, employees are less likely to believe that increasing effort will result in additional pay, thereby leading to lower levels of motivation (Aguinis, 2013). We offer three specific guidelines regarding the imple mentation of this second principle. performance because employees are not likely to First, pay levels must vary significantly based on change their motivation levels when there is a small difference in the amount of pay between high per- formers and low performers (Aguinis, 2013; Rynes, Schwab, &t Heneman, 1983). Even if there is a strong connection between performance and supplemental pay (e.g., bonuses), small amounts of additional remuneration promised for higher performance lev- els will fail to motivate employees to exert the additional effort. Second, it is important to explicitly communicate to employees that they are being paid differently because of different levels of performance and not because of other reasons. As stated by Baldwin, Bommer, and Rubin (2013, p. 262), "Nothing is likely to burn out your star performer as much as equal rewards, whereby everyone receives the same... regardless of performance." Ultimately, it is em- ployees' perceptions of whether rewards are con- tingent on performance that drives them to exert more or less effort (Trevor et al., 2012). To maximize this perception, organizations should not only main- tain a performance contingent monetary reward system but also explicitly communicate the performance contingent nature of the rewards Third, it is important to take cultural norms into account (Aguinis, Joo, & Gottfredson, 2012c). For example, consider the cultural dimension labeled the recipient principles of using ion in nonmonetary yee or organizational gyi SOK an prt 20 wa be is, Joo, & Gottfredson, ent helps an organiza- eviors that contribute als and the bottom The third principle involves the need to reward employees in a timely manner (Aguinis, 2013). It is better to reward employees shortly after they have exhibited exemplary behaviors so that the behavior-reward link is established more clearly. However, assigning a cash bonus to an employee every single time an exemplary behavior occurs is not practically feasible. In light of this, we offer three specific guidelines regarding the realistic and effective implementation of this principle. First, managers can distribute fake currencies or reward points that can later be traded for cash, goods, or services (Merrill, Aldana, Garrett, & Ross, 2011). For example, Dave Warren, president of the manufacturing company Energy Alloys, imple mented a reward program called Energy Bucks. Managers and supervisors carry printouts of fake money that are distributed to employees based on their on-the-job performance on an ongoing basis. At the end of the day, employees can use the fake money to purchase various products at the company store or save it for bigger purchases in the future (Witt, 2005). As another illustration, First Data corporation, a financial services firm, has a program in place called Bravo! designed to "recognize employees for their unique contribution to the company and foster a community of excellence 20 co th err sig th sin 4.5. Principle #5: Use monetary and nonmonetary rewards easure employee per- zed (Chen, Tsai, & Hu, standardizing rating by standardizing the s) but also providing ning on how to accu For example, frame eves standardization erpret and assign nu- behaviors (Aguinis, 2009). and behaviors should correctly decide how The fourth principle is that organizations maintain justice in the reward system (Greenberg, 1990). It is important to have a just reward system not only because it is the right thing to do, but also because employees' perceptions of justice lead to a variety of desirable attitudes (e.g., organizational commit- ment) and behaviors (e.g., performance) while reducing undesirable outcomes (e.g., counterpro- ductive work behaviors) (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). There are three types of justice perceptions in the context of a reward system: distributive justice (i.e., "was the allocation of rewards to various employees just?"), procedural justice (i.e., "were the procedures used to allocate re- wards just?"), and interactional justice (i.e., "did th eft mc ini The fifth principle involves the use of nonmonetary rewards in addition to monetary rewards. The rea son is that nonmonetary rewards serve to develop and motivate employees in ways in which monetary rewards do not (Long & Shields, 2010). As we men- tioned earlier, paying employees more does not necessarily improve their job-relevant knowledge #2 th As 1 247 (7 of 9) - + 70% ORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE 247 248 HUMAN PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFOF m provide just man- we offer ding this is impor that are se, unful- tions and tubog, & Saleh, S. D., & Si employees as a of Applied Psyc Schuppel, C. (2011, clever mon cash www.hrmornin clever-non-cash Schaubroeck, J., St under met and reactions to 93(2), 124 134 Stajkovic, A.D., incentive motiv ogement for Trank, C. Q.. Ryni applicants in ce, when increase base pay sendation y as more able over e, if the variable e.g., de evels, an than feel ce, orga- s eligible nstead of 2013). For pany are epending wer-level y are in a increases the orga- and skills or enrich the characteristics of their jobs rewards typically satisfy these criteria because they (e.... job autonomy, positive impact on others). But, "are usually available there is an unlimited supply of certain nonmonetary rewards are designed to do just praise); all employees are usually eligible; and nonfi- that. For example, valuable training and develop nancial rewards are visible and contingent, [and] ment opportunities, offered as rewards for good usually timely." performance, help not only motivate employees Fourth, we suggest that organizations use mone but also increase their job-relevant knowledge and tary rewards to encourage voluntary participation in skills (Brown & Sitzmann, 2011). Further, greater nonmonetary reward programs that are more direct- discretion over redesigning one's own job as a per ly beneficial to employee or organizational perfor- formance contingent reward motivates employees mance (Dierdorff & Surface, 2008). For example, by satisfying their need for autonomy (Wrzesniewski the food and beverage department in Argasy Casino & Dutton, 2001). Next, we offer four specific imple makes cross-training a nonmonetary reward that an mentation guidelines regarding our fifth principle. employee must earn with good performance. Given First, it is not necessary to limit the provision of such, the department adds 50 cents to an employ nonmonetary rewards to noneconomic rewards, be ee's hourly pay rate for every new skill learned. As a cause nonmonetary is not equivalent to noneconom result of this creative use of both monetary and ic (Long & Shields, 2010). Instead, nonmonetary nonmonetary rewards, the department reported rewards involve not only praise and recognition that it experienced high levels of voluntary partici- but also various goods and services. The difference pation in the training program, as well as improved between monetary and nonmonetary rewards is that attraction of job applicants and retention of em- the former involves cash, whereas the latter can be ployees (Davidson & Freundlich, 2011). relabeled noncash rewards. Examples of nonmone- tary rewards include formal commendations and awards, a favorable mention in company publica- 5. Conclusions tions, receiving praise in public, letters of appreci- ation, status indicators such as an enhanced job Monetary rewards can be a powerful influence on title, a more flexible work schedule, greater job employee motivation and performance. However, autonomy, paid sabbaticals, and more interesting monetary reward systems do not always live up to work (Aguinis, 2013). Other examples of nonmone expectations. A likely reason is the much lamented tary rewards include training and development, science practice gap in management and related tuition reimbursement, coveted parking spaces, a fields (Cascio Et Aguinis, 2008). In other words, al- gym membership, a new piece of furniture, going to though there is considerable empirical research on social events or vacations with coworkers, and even what monetary rewards can and cannot do in terms of an opportunity to get out of one's least favorite improving individual performance, such research project (reserved for top performers only) (Douglas, does not seem to have reached many managers 2012; Schappel, 2011). and other organizational decision-makers. We relied Second, make sure to provide nonmonetary re- on the available research results to distill five prin wards that are need-satisfying for the recipient ciples that, if followed, will allow organizations to because effective nonmonetary rewards motivate take advantage of what monetary reward systems people by satisfying their desires (Long & Shields, have to offer. However, the devil is in the details. 2010). For example, if a manager gives a Celine Dion Thus, we also offered research-based guidelines re- concert ticket to an employee who has no interest in garding the effective implementation of each of the singer, this will likely have no effect on the these five general principles. We hope that the adop employee's motivation or worse, may send the tion of our five principles, as well as their implemen- signal that the manager does not care about tation using our specific guidelines, will allow the employee. This situation can be avoided by organizations to improve their performance by ad- simply asking what the employee wants. dressing employees' number one request: "Show me Third, distribute nonmonetary rewards based on the money!" the other four principles of using monetary rewards effectively. Just like with monetary rewards, non- monetary rewards should be based on accurate def- References initions and measurement of employee performance (Principle #1), contingent on performance (Principle Aguinis, H. (2013). Performance management (3 ed.). Upper #2), provided in a timely manner (Principle #3), and Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K. & Joo, H. (2012a). Delivering the reward systems must be just (Principle #4). effective performance feedback: The strengths based ap As noted by Aguinis (2013, p. 275), nonmonetary preach. Business Horizons, 55(2), 105-111. Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2012). Using perfor- mance management to win the talent war. Business Horizons, 55(6), 609 616. Aguinis, H., Joo, H., & Gottfredson, R. K. (2011). Why we hate performance management and why we should love it. Busi ness Horizons, 546), 503 507. Aguinis, H., Joo, H., & Gollfredson, R. K. (2012). Performance management universals: Think globally and act locally. Busi- ness Horizons, 55(4), 385 392. Aguinis, H., Mazurkiewicz, M.D., & Heggestad, E. D. (2009). Using Web-based frame-of-reference training to decrease biases in personality based job analysis: An experimental field study Personnel Pychology, 77.405 Experimental field study Ambrose, M.L., & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Jour nal of Applied Psychology, 9412) 491 500. Baldwin, T. T. Bommer, W. H., & Rubin, R.S. (2013). Managing organizational behavior: What great managers know and do ed.). New York: McGraw Hill/Irwin. Beer, M., & Cannon, M. D. (2004). Promise and peril in implement- ing pay-for-performance. Human Resource Management, 4311). 3 20. Bardia, P., Restubog, 5.L.D., & Tang, R.L. (2008). When employ- ees strike back Investigating mediating mechanisms between psychological contract breach and workplace deviance. Jour nal of Applied Psychology, 931), 1104 1117. Brown, K G., & Silma, T. (2011). Training and employee development for improved performance. In S. Zedeck (Ed.). A handbook of Industrial and organizational pychology (Vol. 2, pp. 469 503). Washington, DC: American Psychologi- cal Association Brown, M. P, Sturman, M. C., Simmering, M. J. (2003). Com pensation policy and organizational performance. The efficien- cy, operational, and financial implications of pay levels and pay structure. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 752 762 Cadsby, C.B., Song, E., & Tapon, F. (2007). Sorting and incentive effects of pay-for-performance: An experimental investiga- tion. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 387405. Campbell, S., Reeves, D., Kontopantelis, E., Sibbald, B., & Roland, M. (2009). Effects of pay-for-performance on the quality of primary care in England. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(4), 368 378. Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2005). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 935), 1062 1081. Cascia, W.F., & Cappelli, P. (2009, January 1). Lessons from the financial services crisis: Danger lies where questionable ethics intersect with company and individual incentives. HR Mogo- zine. Retrieved July 24, 2012, from http://www.shirm.org/ Publications/hrmagazine/Editorial content/Pages/010ascio. aspx Chechik, J. S. (Director). (1989). National Lampoon's Christmas wacation Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros. Pictures Chen, Y. C., Tsai, W. C., & Hu, C. (2008). The influences of interviewer-related and situational factors on interviewer reactions to high structured job interviews. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1916), 1056-1071 Chib, V.S., De Martino, B., Shimojo, S., & O'Doherty, J. (2012). Neural mechanisms underlying paradacical performance for monetary incentives are driven by loss aversion. Neuron, 743), 582 594 Crowe, C. (Director). (1996). Jerry Maguire Motion picture) United States: Columbia Tristar. Davidson, S., & Freundlich, D. (2011). Cosh borses and incentives. Retrieved July 24, 2012, from http://restaurantbriefing.com/ 2010/03/cash bonuses and incentives/ Dierdorff, E.C., & Surface, E. A. (2008). If you pay for skills, will they learn. Skill change and maintenance under a skill-based pay system. Journal of Managw, 34(4), 721-743. Douglas, E. (2012, March 28). Monetary non-monetary rewards. Which are more attractive? Retrieved July 24, 2012, from http://blogs.odweek.org/topschoolja/k-12 talent_manager/2012/03/monetary_versus_non-monetary rewards which are more attractive.html Du, J., & Chol, J. N. (2010). Pay for performance in emerging markets: Insights from China. Journal of International Busi- ness Studies, 41(0.671 689. Feldman, D.C., Arnold, H. (1978). Position choice: Compar ing the importance of organizational and job factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 6316). 706 710. Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives Academy of Management Arols, 3, 273-331. Greenberg, J. (1990). Employee theft as a reaction to underpay ment inequity. The hidden cost of pay cuts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75), 561 568. Grote, D. (1996). The complete guide to performance appraisal (1* ed.). New York American Management Association. Harris, I., & Bromiley, P. (2007). Incentives to cheat: The influ- ence of executive compensation and firm performance on financial misrepresentation. Organization Science, 18(3), 350 367. Jewell, D.O., & Jewell, S. (1987). An example of economic gainsharing in the restaurant industry. National Productivity Review, 612), 134 14. Kerr, S. (1975). On the folly of rewarding, while hoping for B. Academy of Management Journal, 18(4), 769783 Kuhn, K.M., & Yockey, M.D. (2003). Variable pay as a risky choice: Determinants of the relative attractiveness of incentive plans. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 902), 323 341. Locke, E. A, Feren, D. B., McCaleb, V. M, Shaw, K.N., & Denny A T. (1980). The relative effectiveness of four methods of motivating employee performance. In K. D. Duncan, M. M. Gruenberg, D. Wallis (Fds.), Changes in working life pp. 363 388). New York: Wiley. Long, R. J., & Shields, J. L. (2010). From pay to praise? Non-cash employee recognition in Canadian and Australian firms. Inter national Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(8), 1145 1172 McCloy, R. A, Campbell, J., & Cudeck, R. (1994). A confirma tary test of a model of performance determinants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 7914), 493505. Merrill, R. M., Aldana, S. G., Garrett, J., & Ross, C. (2011). Effectiveness of a workplace wellness program for main taining health and promoting healthy behaviors. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53(7), 782 787. Mitchell, T. R. (1997). Matching motivational strategies with organizational contexts. Research in Organizational Behavior, 19. 57-149. O'Boyle, E., Aguinis, H. (2012). The best and the rest: Revisiting the norm of normality of individual performance. Personnel Psychology, 6541), 79 119. Rynes, S.L., Gerhart, B., & Minette, K. A. (2004). The importance of pay in employee motivation Discrepancies between what people say and what they do. Human Resource Management, 4314), 381 394 Rynes, S. L. Schwab, D., Hereman, H. G. (1983). The role of pay and market pay variability in job application decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 312). 363 364. ice, it is onvincing as budget that make rewards 3. 1990). employ- thorough ted when ayouts or 1 monetary The rea develop monetary we men- does not nowledge 1 241 (1 of 9) - + 70% >> Business Horizons (2013) 56, 741 749 242 HUMAN PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE Available online at www.sciencedirect.com SciVerse ScienceDirect KELLEY SCHOOL OF BUSINESS INDIANA UNIVERSITY www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor ELSEVIER HUMAN PERFORMANCE What monetary rewards can and cannot do: How to show employees the money Herman Aguinis*, Harry Joo, Ryan K. Gottfredson Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 1309 E Tenth Street, Bloomington, IN 47405-1701, U.S.A. to its role as a motivator, greater absol relative to the competition, as wel alignment between monetary reward mance, allow organizations to attra individuals who exhibit the highest le mance, need for achievement, and le ities (Rynes et al., 2004). Further, hi pay and better pay-performance alig pecially valued by top performers: highly sought-after employees wh to the majority of organizations' ou Gottfredson, & Joo, 2012b; O'Boy! 2012). Not surprisingly, organizations higher pay levels and tie pay to indi mance enjoy high levels of return on Sturman, & Simmering, 2003). The reason why monetary rewards erful motivator of employee perform help attract and retain top performe help meet a variety of basic need: shelter) and also higher-level needs (e to a group, receiving respect from oth mastery in one's work) (Long & Shiel example, monetary rewards provic with the means to enhance the well- families, as well as pay for leisure a friends and colleagues, thereby helpi higher-level need to belong in groups. I also use monetary rewards to purcha: bols such as bigger houses (satisfying th need for respect from others) and pe development, or higher education ( higher level need for achieving mast monetary rewards in and of themsel valued as a symbol of one's social st Singh, 1973) and acknowledgment of accomplishment (Trank, Rynes, & Brel ; KEYWORDS Motivation; Compisation; Human resource management; Individual performance; Employee retention Rod: Yeah! Louder! systems that allows us to reconcile seemingly con tradictory conclusions about the positive and nega Jerry: Show me the money!! tive effects of monetary reward systems. However, given the much lamented science-practice divide in Rod: I need to feel you, Jerry! management and related fields (Cascio & Aguinis, 2008), this research does not seem to have reached Jerry: (Screaming) Show me the money!!! Show me many managers and other organizational decision- the money!!! makers. Accordingly, next we discuss what monetary rewards can and cannot do, and why, in terms of Rod: Congratulations, Jerry, you are still my agent. improving employee performance. Then, we offer research-based recommendations including five As was the case for Rod Tidwell, monetary rewards general principles to guide the design of effective can be a very powerful motivator, and the effect that monetary reward systems. In addition, we offer monetary rewards have on motivation often trans specific research-based guidelines regarding the lates into other positive outcomes such as employee implementation of each of these principles. In short, retention (Jewell & Jewell, 1987). Moreover, our article distills research-based findings and offers Stajkovic and Luthans (2001) conducted a study in recommendations that allow for a better under- cluding more than 7,000 employees with identical job standing of when and why monetary reward systems responsibilities and found that objective perfor are likely to be successful in terms of enhancing mance improvements measured in real-time by a employee motivation and performance. meter in each employee's work station-were high- est among employees in a monetary incentive inter- vention program compared to those who received 2. What monetary rewards can do and social recognition or performance feedback instead. why In addition, benefits of monetary rewards seem to be global and have been documented not only in the Examples of monetary rewards include base pay, United States but also in many other countries and cost-of-living adjustments, short-term incentives, industries around the world including China (Du & and long-term incentives (Aguinis, 2013). The avail- Choi, 2010), Australia (Cadsby, Song, & Tapon, 2007), able empirical evidence documents that monetary and England (Campbell, Reeves, Kontopantelis, rewards are among the most powerful factors af- Sibbald, &t Roland, 2009). fecting employee motivation and performance. For However, monetary rewards do not always lead to example, Locke, Feren, McCaleb, Shaw, and Denny desirable outcomes. First, generous amounts of (1980) found that an employee's productivity in monetary incentives sometimes fail to motivate creased by an average of 30% after the introduction (Beer & Cannon, 2004) and may even lead to coun of individual monetary incentives. Other types of terproductive outcomes such as financial misrepre rewards and interventions do not seem to have such sentation activities (Harris & Bromiley, 2007). a powerful effect (Locke et al., 1980; Stajkovic & Second, when promised very high amounts of mon Luthans, 2001). etary incentives, employees can 'choke,' or suffer In spite of the research-based evidence, manag- declined performance levels as a result of sharply ers and other organizational decision-makers often increased fear of failure (Chib, De Martino, Shimojo, seem to lose sight of the principle so eloquently & O'Doherty, 2012). Third, employees can develop a encapsulated by former Avon CEO Hicks Waldron: "it sense of entitlement to certain amounts of payouts took me a long while to learn that people do what (Beer & Cannon, 2004) and, as a result, actual you pay them to do, not what you ask them to do payouts that fall short of their expectations can (Cascio ft Cappelli, 2009). One likely reason for the cause various negative reactions such as pay-level lack of generalized acceptance of this principle is dissatisfaction and intentions to quit the organiza that results of employee surveys seem to suggest tion (Schaubroeck, Shaw, Duffy, & Mitra, 2008). that monetary rewards are not among the most This point is humorously illustrated in National important motivating factors. However, what em- Lampoon's Christmas Vacation (Chechik, 1989), in ployees say is the value of monetary rewards does which the main character Clark Griswold (played by not always reflect what they think or what they Chevy Chase) goes on a bizarre rant in front of his actually do (Rynes, Gerhart, & Minette, 2004). In family after finding out that his usually generous fact, although pay is not often acknowledged as a Christmas cash bonus was not given out for the year. critical factor in most surveys, it is one of the most There is an important body of scholarly research important factors leading employees to accept job on motivation, individual performance, and reward offers (Feldman et Amold, 1978). Thus, in addition Abstract Monetary rewards can be a very powerful determinant of employee motivation and performance which, in turn, can lead to important returns in terms of firm-level performance. However, monetary rewards do not always lead to these desirable outcomes. We discuss in this installation of Human Performance what monetary rewards can and cannot do, and reasons why, in terms of improving employee performance. Also, we offer research-based recommendations including the following five general principles to guide the design of successful monetary reward systems: (1) define and measure performance accurately, (2) make rewards contin- gent on performance, (3) reward employees in a timely manner, (4) maintain justice in the reward system, and (5) use monetary and nonmonetary rewards. In addition, we offer specific research-based guidelines for implementing each of the five principles. In short, our article summarizes research-based findings and offers recommendations that will allow managers and other organizational decision makers to understand when and why monetary reward systems are likely to be successful in terms of enhancing employee motivation and performance. 2012 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Show me the money Jerry: What can I do for you, Rod? You just tell me. What can I do for you? A well-known scene from the movie Jerry Maguire (Crowe, 1996) portrays the high value that employ- Rod: It's a very personal, a very important thing. ees give to monetary rewards. The scene involves Are you ready, Jerry? the following shortened telephone conversation be- tween Jerry Maguire, a sports agent played by Tom Jerry: I'm ready Cruise, and Rod Tidwell, a National Football League wide receiver played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.: Rod: Here it is: Show me the money. Oh-ho-ho! Show! Me! The! Money! A-ha-ha! Jerry, doesn't it make you feel good just to say that? Say it with me one time, Jerry! Corresponding author E-mail address: haguinis indiana.edu (H. Aguinis) Jerry: Show me the money! : 0007-6813/$ se front matter 2012 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor 2012.11.007 3. What monetary rewards ca and why There are limitations to what monetar do in terms of enhancing individual ar mance. First, monetary rewards do employees' job-relevant knowledge abilities (KSAs). That is, although mon can motivate employees to work harde necessarily improve KSAs, unless mon are invested in training and developn (Dierdorff & Surface, 2008). Individual is determined by both motivation and Campbell, & Cudeck, 1994). So, relyin rewards as the exclusive solution to problems is counterproductive when poor performance is a lack of KSAs ratt 11 - + 70% >> HUMAN PE much em have grea sired out placed on ample, iti behaviors reasonabl necessary tasks (Agi 4.2. Prir continge and 243 (3 of 9) PERFORMANCE HUMAN PERFORMANCE 243 244 HUMAN PERFORMANCE eemingly con to its role as a motivator, greater absolute pay levels of motivation (Mitchell, 1997). As noted by Aguinis Table 1. Research-based recommendations on principles and implementation guidelines for using monetary tive and nega relative to the competition, as well as a better (2013, p. 275). "[if an organization is trying to solve rewards effectively ems. However, alignment between monetary rewards and perfor performance problems by focusing on money only, Principles Implementation Guidelines actice divide in mance, allow organizations to attract and retain one result is expected for sure: The organization will 1. Define and measure ecio e Aguinis, individuals who exhibit the highest levels of perfor- Specify what employees are expected to do, as well as what they should refrain spend a lot of money." performance accurately from doing. have reached mance, need for achievement, and leadership qual Second, monetary rewards do not necessarily Align employees' performance with the strategic goals of the organtzation. Tonal decision ities (Rynes et al., 2004). Further, higher levels of improve the quality of jobs: what is generally la Standardize the methods used to measure employee performance. vhat monetary pay and better pay-performance alignment are es beled 'job enrichment' (Grant & Parker, 2009). Job Measure both behaviors and results. But, the greater the control that employees my, in terms of pecially valued by top performers: a minority of enrichment is an important motivator because indi- have over the achievement of desired outcomes, the greater the emphasis should Then, we offer highly sought-after employees who contribute viduals derive personal meaning from enriched jobs. be on measuring results. including five to the majority of organizations' output (Aguinis, For example, increasing employees' pay levels does 2. Make rewards contingent Ensure that pay levels vary significantly based on performance levels. en of effective Gottfredson, & Joo, 2012b; O'Boyle at Aguinis, not necessarily enhance the level of autonomy and on performance Explicitly communicate that differences in pay levels are due to different levels Lion, we offer 2012). Not surprisingly, organizations that provide participation in decision-making enjoyed by em- of performance and not because of other reasons. regarding the higher pay levels and tie pay to individual perfor ployees. Also, monetary rewards per se do not Take cultural norms into account. For example, consider individualism-collectivism iples. In short, mance enjoy high levels of return on assets (Brown, enrich jobs by enhancing the variety of skills that when deciding how much emphasis to place on rewarding individual versus team lings and offers performance. Sturman, & Simmering, 2003). employees use at their jobs or the perception of better under The reason why monetary rewards can be a pow positive impact that employees' work has on others. 3. Reward employees Distribute fake currencies or reward points that can later be traded for cash, eward systems erful motivator of employee performance and also Finally, monetary rewards do not have a built-in in a timely manner goods, or services. of enhancing help attract and retain top performers is that they mechanism that prevents such rewards from unin- Switch from a performance appraisal system to a performance management system, which encourages timely rewards through ongoing and regular help meet a variety of basic needs (e.g., food, tentionally encouraging unethical and counterpro evaluations, feedback, and developmental opportunities. shelter) and also higher-level needs (e.g., belonging ductive employee behaviors (Kerr, 1975). For Provide a specific and accurate explanation regarding why the employee received to a group, receiving respect from others, achieving instance, Green Giant, a producer of frozen and the particular reward. an do and mastery in one's work) (Long & Shields, 2010). For canned vegetables, once rewarded its employees 4. Maintain justice in Only promise rewards that are available. example, monetary rewards provide employees for removing insects from vegetables. It was later with the means to enhance the well-being of their When increasing monetary rewards, increase employees' variable pay levels the reward system found that employees began to bring insects from instead of their base pay. ude base pay. families, as well as pay for leisure activities with their homes, placed them in the vegetables, and Make all employees eligible to earn rewards from any incentive plan. . rm incentives, friends and colleagues, thereby helping satisfy the subsequently removed them to receive the mone- Communicate reasons for any failure to provide promised rewards, changes in the 13). The avail- higher-level need to belong in groups. Employees can tary rewards (Aguinis, 2013). amount of payouts, or changes in the reward system. that monetary also use monetary rewards to purchase status sym In sum, monetary rewards can improve employee 5. Use monetary and Do not limit the provision of nonmonetary rewards to noneconomic rewards. ful factors al- bols such as bigger houses (satisfying the higher-level motivation and performance because they can sat- nonmonetary rewards Rather, use not only praise and recognition, but also noncash awards consisting of formance. For need for respect from others) and pursue training, isfy a wide range of low- and high-level needs (Long various goods services. saw, and Denny development, or higher education (satisfying the & Shields, 2010). However, the use of monetary Provide nonmonetary rewards that are need satisfying for the recipient. roductivity in higher level need for achieving mastery). Further, rewards does not always lead to desirable out- Distribute nonmonetary rewards based on the other four principles of using ne introduction monetary rewards in and of themselves are often comes. Next, we offer research-based recommen- monetary rewards effectively. Other types of valued as a symbol of one's social status (Saleh & dations on how to design and implement effective Use monetary rewards to encourage voluntary participation in nonmonetary m to have such Singh, 1973) and acknowledgment of one's personal monetary reward systems that will maximize posi- reward programs that are more directly beneficial to employee or organizational performance 0; Stajkovic & accomplishment (Trank, Rynes, & Bretz, 2002). tive outcomes and minimize negative ones. dence, manag performance measures must be reliable (.e., yield goals of the organization (Aguinis, Joo, & Gottfredson, -makers often 3. What monetary rewards cannot do 4. Best-practice recommendations on consistent and error-free scores across raters, time, 2011). Establishing this alignment helps an organiza- so eloquently and why how to use monetary rewards or other contexts) and also valid (i.e., reflect all tion promote employee behaviors that contribute ks Waldron: "It effectively relevant performance facets and not irrelevant to meeting organizational goals and the bottom eople do what There are limitations to what monetary rewards can ones) (Aguinis, 2013). line. k them to do" do in terms of enhancing individual and firm perfor There are four guidelines regarding how to im- Our best-practice recommendations regarding how Third, methods used to measure employee per- reason for the mance. First, monetary rewards do not improve to use monetary rewards effectively include five plement this first principle. First, there is a need to formance should be standardized (Chen, Tsai, & Hu, mis principle is employees' job-relevant knowledge, skills, and general principles, each of which is accompanied specify what employees are expected to do, as well 2008). This involves not only standardizing rating em to suggest abilities (KSAs). That is, although monetary rewards by specific guidelines regarding implementation is- as what they must refrain from doing. Otherwise, forms and techniques (e.g., by standardizing the song the most can motivate employees to work harder, they do not sues. Table 1 provides a brief summary of our rec- employees may increase performance in areas that questions asked in interviews) but also providing ver, what em- necessarily improve KSAs, unless monetary rewards ommendations. are not desired by the organization, including coun raters with standardized training on how to accu rewards does are invested in training and development activities terproductive behaviors illustrated earlier through rately measure performance. For example, frame- or what they (Dierdorff & Surface, 2008). Individual performance 4.1. Principle #1: Define and measure the Green Giant example. In short, inaccurate def of-reference training achieves standardization ette, 2004). In is determined by both motivation and KSAS (McCloy. performance accurately initions and measures of performance may lead to by helping raters similarly interpret and assign nu- owledged as a Campbell, & Cudeck, 1994). So, relying on monetary the fallacy of rewarding A, while hoping for B (Kerr, merical scores to the same behaviors (Aguinis, ne of the most rewards as the exclusive solution to performance Performance should be defined and measured accu- 1975). Mazurkiewicz, & Heggestad, 2009). to accept job problems is counterproductive when the cause for rately for a monetary reward system to be truly Second, when defining performance, we suggest Fourth, though both results and behaviors should us,