Question: Please read the question Question : Using the text shar e what you feel were the most important educational reforms of the last century (pick

Please read the question

Question: Using the text share what you feel were the most important educational reforms of the last century (pick at least two). Why do you see them as so fundamental? Explain why?

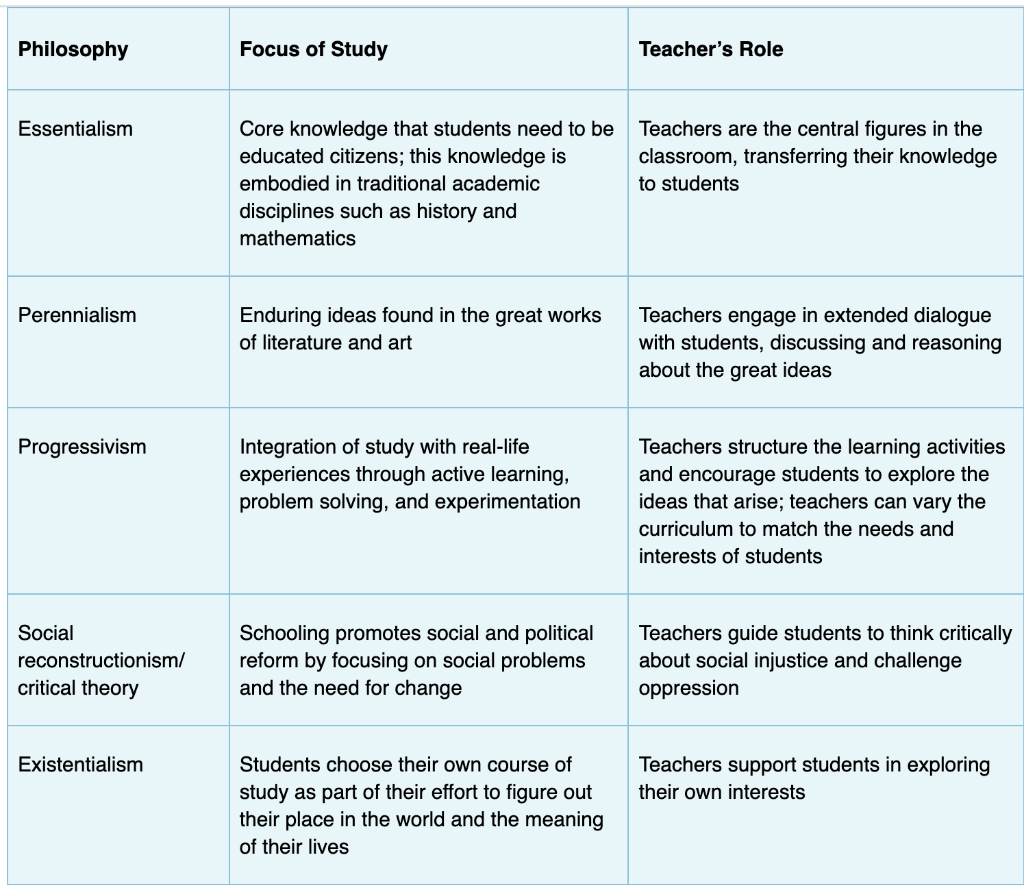

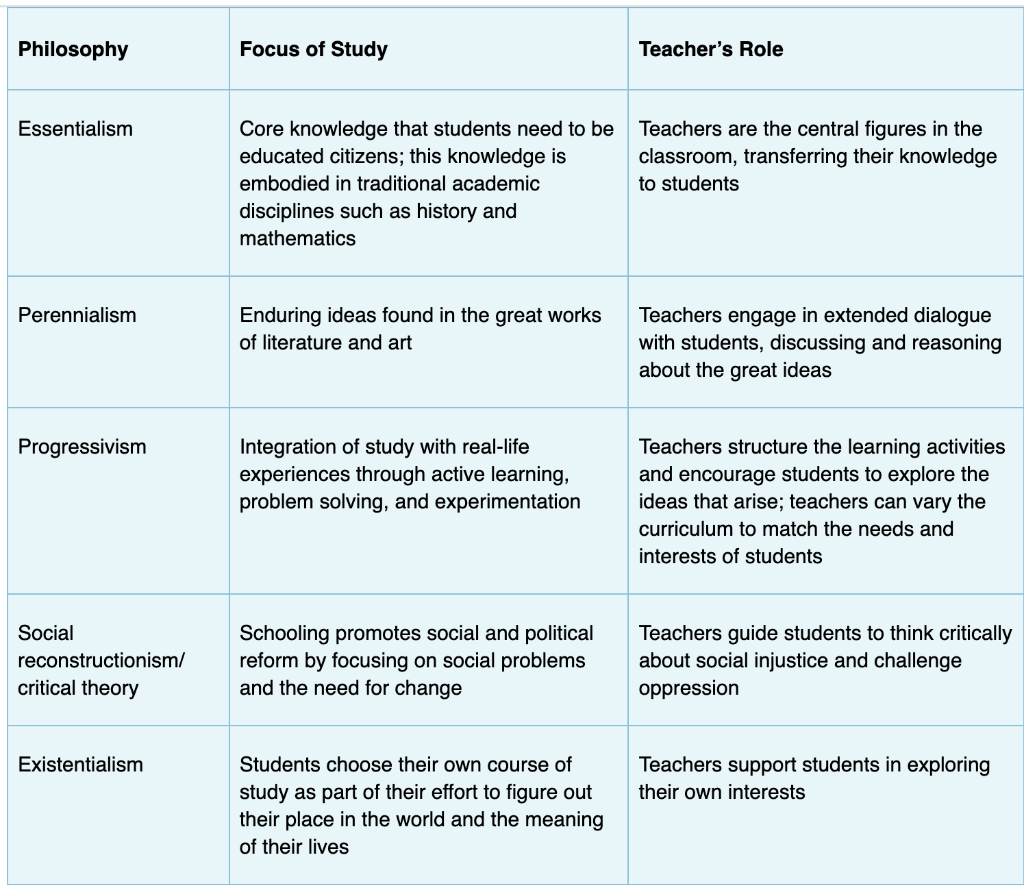

Teaching has a long and impassioned history in the United States. Knowing what and who came before us gives us a deeper understanding of our mission as we move forward. We teach in a contemporary context; the culture of that context, like the culture of an individual school, shapes our practice now more than ever in our nation's history. We are living at a time when private foundations and federal and state governments are designing solutions to problems that besiege public schooling in the United States. There are few who doubt that teachers make a huge difference that it is better to be in a poorer school with a great teacher than a richer school with a terrible teacher. Still, amidst the fuss is the challenge of how to evaluate a "terrific teacher and what "terrific, "successful," or "great" teachers look like. Reasonable doubts remain about effective school reform, and even more doubts about the best way to educate future teachers like you. In order to assess teacher candidates' readiness to teach, the edTPA, which was introduced in Chapter 2, was developed. The topics that this assessment ask you to become knowledgeable about are addressed by this text. American schools are represented by wide varieties including a tapestry of experimental and traditional public schools, all designed to ensure a literate populace in a democratic society. Simultaneously, the digital revolution is transforming the meaning of teaching and learning as "delivery systems," providing online courses for precollege students. Many of you may have taken these online courses en route to earning your high school diploma. Teaching online may be a route you will want to take. There is so much information available online that it can challenge our thinking about what we need to know and be able to do as educated women and men. It also challenges our skills as teachers, since teaching and learning are two sides of the same coin. It is a dialectic and requires an exchange of ideas. Teaching is not "telling," and online teaching and learning is far more than a delivery system. Against this backdrop of rapid change and confusing options, this chapter provides an overview of the history of education in the United States to give you a historical context for where we are today. What do you picture in your mind when you think of an elementary school? A middle school? A high school? Did any of you attend a junior high school? The history of U.S. public education reflects the changes that an emerging nation endures as it matures and ensures that all of its citizens become educated. Learning about the evolution of public schools in our country reminds us that free societies require an educated populace, one where people understand their choices in a diverse society. Like many other complex histories, the history of education reveals the changing belief systems of the times. As the pendulum swings from more rigid governance of the schools to more flexible governance and back again, the main goal and hope is that all its citizens will have access to, and participate in, the process of becoming educated through a public school system designed to meet their needs. The Swinging Pendulum: Dominant Philosophies Influencing Education The struggle to change or reform educational practices is as old as organized public schooling. From common school days to present times, the content and processes of education have been under continuous scrutiny. Schools, like other public institutions, are products of their times politically, socially, and economically. Schools both reflect and influence the societal events of their day. We are all a part of what we are trying to change. As teachers and future teachers, we seek a profession dedicated to student learning. As citizens, we know that, as Thomas Jefferson observed, it is impossible for a nation to be both free and ignorant. But we are people of diverse regions, ethnicities, and social and economic backgrounds, and to be successful educators we need to make sense of (1) who we are in the world and (2) what conditions we believe are important for learning to occur. At different periods in our history, different philosophies have dominated our thinking about teaching and learning, and about the manner in which education should proceed. In this section, we look at several competing philosophies that have shaped efforts to reform U.S. schools since late in the 19th century. Many classrooms today are hybrids of several of these philosophies of education. As you read this section, think about what is happening in schools today and how the current phase of U.S. public education will be viewed by others 50 years from now. During this recent era of standardization and testing, which of these philosophies appears to dominate? Enduring Ideas: The Influence of Perennialism An educational philosophy related to essentialism, perennialism stresses the belief that all knowledge or wisdom has been accumulated over time and is represented by the great works of literature and art as well as religious texts. This educational philosophy found a strong expression in the 1980s with the Paideia Proposal by Mortimer Adler. In this influential call for school reform, Adler proposed one universal curriculum for elementary and secondary students, allowing for no electives. Everyone would take the same courses, and the curriculum would reflect the enduring ideas found in the works of history's finest thinkers and writers. Like essentialism, perennialism holds that one type of education is good for all students. It differs from essentialism by placing greater emphasis on classic works of literature, history, art, and philosophy (including works of the ancient Greeks and Romans), and on the teaching of values and moral character. Essentialism can include practical, vocation-oriented courses-a class in computer skills, for instance-but perennialism leaves little room for such frivolity. The perennialist approach has found a home at several U.S. colleges, such as St. John's College in Maryland and in the state of New Mexico, and its influence shows in the core curricula at some larger universities, including the University of Chicago and Columbia University. Threads of the perennialist philosophy are present in many parochial schools as well. Whenever you hear about a program centered on great ideas or great books," it most likely reflects perennialist ideas. Adler emphasized the Socratic Method, a type of teaching based on extensive discussion with students. In this respect, he was somewhat less teacher centered than many essentialists. His perennialism does, however, leave little room for flexibility in the curriculum and little opportunity to reflect the changing demographics of our times. Radical Reform Philosophies: Social Reconstructionism, Critical Theory, and Existentialism Alongside essentialism, progressivism, and perennialism, the 20th century gave rise to some radical reform philosophies that proposed a fundamental rethinking of the nature of schooling. Among these are social reconstructionism, critical theory, and existentialism. Social reconstructionism is an educational philosophy that emphasizes social justice and a curriculum promoting social reform. Responding to the vast inequities in society and recognizing the plight of the poor, social reconstructionists believe that schools must produce an agenda for social change. Linked with social reconstructionism is critical theory or critical pedagogy, which stresses that students should learn to challenge oppression. In this view, education should tackle the real-world problems of hunger, violence, poverty, and inequality. Clearly, students are at the center of this curriculum with teachers advocating involvement in social reform. The focus of critical theorists and social reconstructionists is the transformation of systems of oppression through education to improve the human condition. perennialism An educational philosophy that emphasizes enduring ideas conveyed through the study of great works of literature and art. Perennialists believe in a single core curriculum for everyone. Among critical theorists, Paulo Freire (1921-1997), a Brazilian whose experiences living in poverty led him to champion education and literacy as the vehicle for social change, has had a particularly profound impact on the thinking of many educators. His most influential work was Pedagogy of the Oppressed, published in English in 1970. Another philosophy that proposes fundamental changes in education is existentialism, which posits student- centered learning as the ideal. Rooted in the thinking of 19th-century philosophers like Sren Kierkegaard, existentialism gained popular notice in the mid-20th century through the works of Jean Paul Sartre and others. According to this philosophy, the only authoritative truth lies within the individual. Existentialism is defined by what it rejects-namely, the existence of any source of objective truth other than the individual person, who must seek the meaning of his or her own existence. Aesthetics and Maxine Greene We want to expand the range of literacy, offering the young new ways of symbolizing, new ways of structuring their experience, so they can see more, hear more, make more connections, embark on unfamiliar adventures into meaning. - Maxine Greene (2001) In this era of global interdependence and multicultural diversity, educators continue to develop their ideas about the purposes of education and the best ways to reform schools. One influential contemporary thinker is the late Maxine Greene, a U.S. philosopher, social activist, and teacher who was an active scholar and educator at Teachers College, Columbia University, from 1965 until her death in 2014. She believed that the role of education is to create meaning in the lives of students and teachers through an interaction between knowledge and experience with the world. Greene's educational philosophy was rooted in Dewey's ideas about art and aesthetics. Dewey's democratic view of education suggested that when children are able to approach problem solving artistically and imaginatively, they grow socially and culturally through their shared experiences, insights, and understandings. Therefore, the arts are an essential part of the human experience. Table 3.1 Key Elements of Five Education Philosophies Philosophy Focus of Study Teacher's Role Essentialism Core knowledge that students need to be educated citizens; this knowledge is embodied in traditional academic disciplines such as history and mathematics Teachers are the central figures in the classroom, transferring their knowledge to students Perennialism Enduring ideas found in the great works of literature and art Teachers engage in extended dialogue with students, discussing and reasoning about the great ideas Progressivism Integration of study with real-life experiences through active learning, problem solving, and experimentation Teachers structure the learning activities and encourage students to explore the ideas that arise; teachers can vary the curriculum to match the needs and interests of students Social reconstructionism/ critical theory Schooling promotes social and political reform by focusing on social problems and the need for change Teachers guide students to think critically about social injustice and challenge oppression Existentialism Teachers support students in exploring their own interests Students choose their own course of study as part of their effort to figure out their place in the world and the meaning of their lives Educational Reform: Funding, Priorities, and Standards Although education of the citizenry was important to the founders of the United States, there is no mention of education for all in the Constitution. Hence, schooling became the domain and responsibility of the states, which left most of the control of schools to local communities. Thus, U.S. schools have traditionally been run by local school boards, and the bulk of the money they need has been raised through local taxes, especially property taxes. Many critics have argued that the reliance on local property taxes is unfair because it means that wealthier districts can raise more money for schools than poorer districts can. Yet Americans have long been reluctant to give up local funding and the control that goes with it. As we noted previously, however, the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik in 1957 prompted a rethinking of U.S. educational priorities. Federal and state governments increasingly began to intervene in educational matters, setting priorities and (at least sometimes) providing funds to make sure those priorities were met. The overall result of these changes is that local school districts receive federal money to implement reform movements in their districts. Although local schools are happy to receive government money, they are not always pleased that the funds come with strings attached, reducing local control over the way schools operate. The following sections introduce you to several ways in which government legislation, publications, and court cases have changed the course of U.S. public education. A Nation at Risk In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education, a group of scholars and educators convened by the U.S. Department of Education, issued a report in the form of an open letter to the U.S. people. Called A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform, this document showed deep concern about the educational system in the United States: Our society and its educational institutions seem to have lost sight of the basic purposes of schooling, and of the high expectations and disciplined effort needed to attain them. This report, the result of 18 months of study, seeks to generate reform of our educational system in fundamental ways and to renew the Nation's commitment to schools and colleges of high quality throughout the length and breadth of our land. (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983, p. 1) The report called for tougher standards for graduation, increases in the required number of mathematics and science courses, higher college entrance requirements, and a return to what was called academic basics." It also defined "computer skills as a new basic. The report further recommended an increase in the amount of homework given, a longer school day, more rigorous requirements for teachers, and updated textbooks. A Nation at Risk inaugurated a new period of academic rigor, with increased attention to skills and standards, and less emphasis on progressive concerns such as schools' role in building social understanding. The at risk wording implied that the United States would lose its global competitive edge if the reforms were not carried out. Even though these recommendations came from the federal government, they were implemented (or sometimes ignored) in different ways at the local, state, and district levels. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act In 1975, Congress passed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142) to ensure that all children with disabilities could receive free, appropriate public education, just like other children. This law was revised in 1990, in 1997, and most recently in 2004. It is now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act What is so important about this act? Before 1975, there was no organized, equitable way of addressing the needs of disabled students in the public school system. Often they were marginalized, taught in separate classrooms, and provided with watered-down curricula. A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform A 1983 federal report that found U.S. schools in serious trouble and inaugurated a new wave of school reform focused on academic basics and higher standards for student achievement. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act The federal law that guarantees that all children with disabilities receive free, appropriate public education. As a result of the federal legislation, however, strong efforts have been made to include students with disabilities in regular classrooms. This reform, known as inclusion, has been implemented to greater or lesser degrees in different school districts. In some classrooms, students with learning disabilities are integrated with general education students as much as possible. In other classrooms, students with special educational needs are included in the general education classroom some of the time; this arrangement is called partial inclusion. Some districts have a self-contained class as well for students with special needs (who are often called special education students). Often, depending on the needs of the student population, all three models exist in the same school district. Reform movements on behalf of children with disabilities have dominated special education programs for the past 30 years. Much educational research suggests that inclusion benefits both special education students and students from the general population. We will return to the subject of inclusion in Chapter 6. Standards-Based Reform As a response to A Nation at Risk and similar publications that followed, groups of scholars from content area associations developed standards for their disciplines, beginning with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. The first version of Principles and Standards for School Mathematics appeared in 1989. Language arts, science, social studies, and foreign languages followed in the 1990s, developing standards for what children at each grade level from prekindergarten to Grade 12 should know and be able to do in each of the content areas. States were asked to prepare content standards based on these national guidelines and to create assessments to match the standards. Hence, the era in which we are presently living-and in which you are preparing to teach-is dominated by standards-based school reform and assessments. Many of you went to school as the standards-based movement was getting under way. Standards in the academic area were developed by professional organizations in concert with scholars and teachers in the field. Standards-based educational reform refers to clear, measurable academic standards for all school students in all academic areas. inclusion The practice of educating students with disabilities in regular classrooms alongside nondisabled students. NCLB and ESSA National standards and the testing that assesses whether students are meeting those standards is a policy issue that has supporters and critics. This movement, supported in part by NCLB, is a model of considerable rigor, accountability, and strict benchmarks for student learning. Supporters of the movement contend that this reform movement encourages schools to set higher standards for their students and to find ways in which their students can meet those standards. Critics insist that curriculum needs to be connected to the students' lived experiences and that standards will stifle innovation and creativity in the classroom. NCLB (signed by President George W. Bush in January 2002) was the most dramatic federal education legislation since ESEA. Although NCLB was a reauthorization and revision of ESEA, it went beyond the previous act in several important ways. It increased funding for less-wealthy school districts and emphasized higher achievement for financially poor and minority students. It also introduced new measures for holding schools accountable for students' progress. Most controversially, NCLB set new rules for standardized testing, requiring that students in Grades 3 through 8 be tested every year in mathematics and reading. This requirement had important implications for the way the curriculum was developed and implemented in many elementary schools across the country. Because of the initial push for statewide standardized tests in mathematics and reading, elementary students in the first decade of this century received less instruction in science and social studies. For many educators, the promise of the NCLB legislation became a massive testing movement, and there has not been substantial research to demonstrate that these standards-based assessments actually improved student learning. The controversy centers on the notion that there was so much at stake from one standardized assessment in either mathematics or language arts. It is important to remember, however, that NCLB asked public schools to be accountable for the progress their students make in these areas. Prior to NCLB, this level of accountability had not existed. This was very significant for American public education because it resulted in using data to reveal the achievement gap between White middle class and poor minority communities. Common Core State Standards The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Initiative is a state-led effort coordinated by the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) to develop a clear and consistent framework to prepare students for college and the workforce through the collaboration with teachers, school administrators, and experts. The standards are designed to provide teachers and parents with a common understanding of what students are expected to learn. Consistent standards will provide appropriate benchmarks for all students, regardless of where they live. These standards define the knowledge and skills students should have within their K-12 education careers so that they will graduate from high school able to succeed in entry-level, credit-bearing academic college courses and in workforce training programs (CCSS, n.d.). These standards have been adopted by 42 states, the District of Columbia, four territories, and the Department of Defense Education Activity (CCSS, n.d.). States not adopting the CCSS are Alaska, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas, Indiana, Virginia, and South Carolina. Many reasons inform their decisions not to adopt the CCSS, including lack of resources for teacher professional development and the desire to maintain control over local standards for teaching and learning mathematics and language arts. In 2009, the first official public draft of the college- and career-readiness standards in English language arts (ELA) and mathematics were released. Care was taken to ensure that these standards in mathematics and English could be used broadly for every state in the country and are designed to influence the development of high-quality curricula in each state. For teachers and students, using curriculum aligned with the CCSS is challenging; in ELA, for example, CCSS asks both teachers and students to spend more time instructionally on nonfiction texts. The CCSS fosters the development of students' skills at citing evidence in what they read for claims they make about its meaning. This involves close reading of texts, enabling students to critically examine the meanings of informational narratives. Similarly, the CCSS in mathematics asks students and teachers to examine the processes and number sense behind mathematical computations in ways that promote deep understanding of mathematical functions. The standards have been met with some resistance, as they represent new approaches to teaching and learning in ELA and mathematics. The CCSS are a significant part of statewide initiatives for educational reform. Improvements in public schooling require experimentation and innovation in the design of the school. As we will see in later chapters, this has led to a proliferation of charter schools, supported by public funds and existing under a special state charter with its own set of standards