Question: Please read the question Question : What strategies have you used to communicate in a language you were acquiring? What strategies do you think emergent

Please read the question

Question: What strategies have you used to communicate in a language you were acquiring? What strategies do you think emergent bilinguals use?

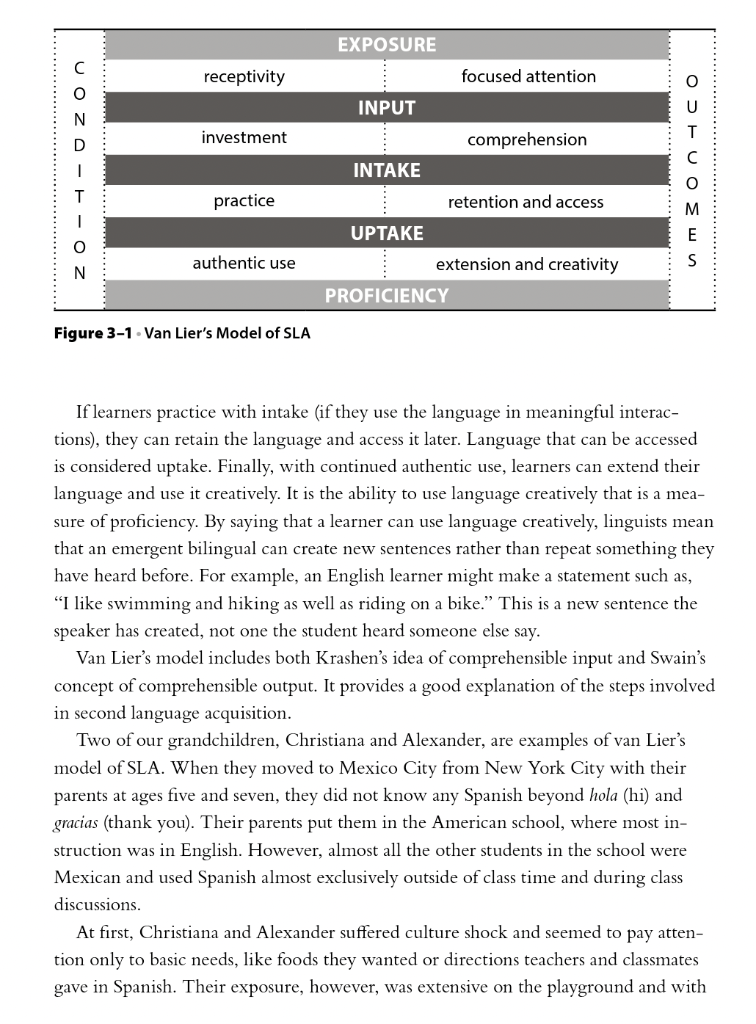

3 How Do People Learn and How Do They Acquire Language? Key Points Learning and language acquisition occur during social interaction in different contexts. Vygotsky claims that students learn when instruction is targeted to their zone of proximal development . Goodman and Goodman argue that teachers should encourage personal invention in the context of social conventions to promote learning. Vygotsky distinguishes between spontaneous concepts acquired through everyday experience and scientific concepts developed in school. Cummins distinguishes between academic and conversational language as emergent bilinguals learn a new language. Two types of linguistic competence are communicative competence and grammatical competence. Krashen's monitor model for language acquisition consists of five hypotheses: the acquisition versus learning, natural order, monitor, input, and affective filter hypotheses. Swain has proposed that output plays a key role in second language acquisition. Van Lier's model of language acquisition includes both input and output. Before examining research and theories of language acquisition, in this chapter we consider how people learn generally. The model of learning we present holds that all learning, including language learning, must always be regarded as a social process. This is the view Halliday (1982) developed. He argued that we learn language, we learn through language, and we learn about language. As Halliday explained, children learn language through social interactions. As they learn language, they learn about the world around them by using language. In schools chil- dren learn about language as they study language as a subject Faltis and Hudelson point out, Learning and language acquisition overlap to a great extent in the sense that both are social, contextual, and goal- oriented. That is, individuals learn both content and language as they engage with others in a variety of settings to accomplish specific purposes (1998, 85). While it is generally accepted that children go through a process of creative construction as they form and test hypotheses about academic content subjects and language, the learning they do is always social. According to Faltis and Hudelson, "learning does not happen exclusively inside the heads of learners; it results from social interactions with oth- ers that enable learners to participate by drawing on past and present experiences and relating them to the specific context at hand in some meaningful way (87). A recent comprehensive review of research on learning by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine states, The committee has taken a sociocul- tural view of learning" (2018, 22). The authors (the Committee on How People Learn II) draw on the work of Cole and Wertsch, who explain the importance of the work of three theorists, Vygotsky, Luria, and Leontiev, also known as the troika of pioneers in sociocultural, social-historical, or cultural-historical theories of development (Cole 1998; Wertsch 1991). The review of research also relies on the work of John-Steiner and Mahn (1996), who show that social, cultural, and historical contexts define and shape children and their experiences. They explain, The underlying principle in this body of work is that cognitive growth happens because of social interactions in which children and their more advanced peers or adults work jointly to solve problems. (26) The research the committee reviews in detail confirms the view that learning oc- curs in social interaction. This finding is particularly important for teaching and learn- ing languages and should influence how teachers teach language in schools. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK In this section we have described a social view of learning. In what ways does your teaching reflect this view? Share one specific example. Vygotsky's Social View of Learning The report of the Committee on How People Learn II is built on the work of Vygotsky and his colleagues. Vygotsky (1962) developed a social theory of learning that included two important concepts: the zone of proximal development (ZPD) and the distinction between spontaneous and scientific concepts. Zone of Proximal Development Based on his research, Vygotsky argued that for learning to take place, instruction must occur in a student's zone of proximal development, which he defined as the dis- tance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers (1978, 86). According to Vygotsky, learning results as we interact with someone else, an adult or a more capable peer, in the process of trying to solve a problem. This applies to both learning about the world and acquiring fuller proficiency in one or more languages. Vygotsky explains that the learner has a certain zone in which the next learning can take place. For example, a student might use the -ing forms of verbs to express progressive tense, as in I studying English. The next area of learning for this student might be to add the auxiliary verb am to produce a more conventional sentence: I am studying English. The teacher, recognizing a teachable moment, could point out the correct form, and this could help the student begin to use the auxiliary. However, un- til the student begins to use the -ing form, attempts to have them add the auxiliary are usually not effective. Students might also notice auxiliaries as they interact with more proficient English speakers and then incorporate them into their speech and writing. A student who already uses auxiliaries would not benefit from instruction on this topic, and a student who is just beginning to study English and uses only simple present tense, such as, I study English, would not be ready to add the auxiliary because it would be beyond the student's learning zone. The ZPD refers to the area that is just beyond what the student can currently do. Good teachers try to aim instruction at this zone by building background and scaffolding instruction. They also plan regular pair and small-group work so students can learn from one another. Another way to think about the ZPD is to consider two students who both score 60 percent on a math test. This score would represent their independent level. A teacher might work with both students and then retest them. One student's score might rise to 70 percent while the other student might get an 80 on the second test. This would suggest that the two students had different zones of proximal develop- ment. One was ready to take a big leap with a little help, while the other could make only a modest gain. Yvonne remembers her statistics class as a graduate student. She had a math pho- bia and a weak background in math in general. The textbook was way beyond her zone of proximal development. The instructor was good and helped her understand through class lectures, but it was when she was part of a study group that she was able to understand enough to pass the statistics exams. She did not excel, but that social interaction with her peers moved her into her zone, which was enough to allow her to understand the basics and pass the course. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Vygotsky's concept of a zone of proximal development is widely accepted and forms the basis for scaffolded instruction. Sometimes students already know what is being taught and are not pushed into that zone of new learning and sometimes the instruction even with scaffolding is far beyond someone's one of proximal development. Think of a specific example of a time when your own learning occurred in your ZPD because of the support you received and one example of when the instruction you received was either in your zone of independent learning (you could do it on your own and the instruction was not useful) or was beyond your zone. Share your examples and try to observe how the ZPD works in your class or in your life more generally. Personal Invention and Social Convention Central to the concept of the zone of proximal development is the view of learning as a process of internalizing social experience. Vygotsky emphasized the role of social forces working on the individual. Goodman and Goodman, however, argue that lan- guage [and other aspects of learning are] as much personal invention as social conven- tion (1990, 231). The Goodmans present a view of learning that recognizes both the effects of social forces and the efforts of individual learners: Human learners are not passively manipulated by their social experiences; they are actively seeking sense in the world (231). Social interaction is crucial. Individuals present their personal inven- tions to others, who provide feedback the learners can use to make their inventions conform, to a greater or lesser degree, with social conventions. We see this process occur when young children begin to write and invent spellings for the words they use. Over time, if teachers and peers respond to the messages they are attempting to express and if children are exposed to lots of print, their spellings change, moving steadily toward conventional usage. The key is to achieve a balance between the two forces of invention and convention. The Goodmans compare inven- tion and convention with the centripetal and centrifugal forces that keep a satellite revolving around Earth. Both forces are needed to keep the satellite in orbit. In the same way, in classrooms, if students are allowed to write any way they wish, they may produce spellings no one can read. On the other hand, if teachers insist on correct spelling, some students may choose not to write at all. Helen was able to help her student Magdalena shape her personal inventions move toward social conventions by engaging her in a writing workshop and being sure she was exposed to lots of reading. Helen wrote: At the beginning of the year, Magdalena was not concerned if her work was readable or followed any of the conventions of standard English. She knew she was putting down her thoughts and ideas, and that was what I emphasized to her. I felt confident that her spelling and grammar would come along if she felt more comfortable in class, was allowed to write in a writer's workshop environment, and was exposed to more texts during reading times. I decided to follow my instincts and only focus on one area with Magdalena. I wanted her to understand that writing is a process and that her misspellings were normal for a child who knew two languages. Recently, she started asking more questions about sentence structures and about the "right way to spell . During a conference time with her group, she and I worked together to pick out the types of words she seemed to misspell or misuse most often. Then we problem solved the reasons why these words might cause her grief when writing. Most of the words we found were words she could spell correctly when she reread her writing. a Helen encouraged Magdalena to invent spellings to get her ideas down on paper. At first, Magdalena was not concerned with correct spellings. However, in the context of a writing workshop and rich reading experiences, Magdalena wanted her teacher and other students to be able to read what she had written, so she started to ask her teacher how to spell words. Helen helped Magdalena develop strategies that allowed this English learner to make her writing more conventional. If Helen had insisted on correct spelling from the beginning, Magdalena probably would not have developed the confidence to write. Helen took her cue from her student and helped her focus on spelling once Magdalena had produced writing she wanted others to read. By taking this approach, Helen provided instruction in Magdalena's ZPD. When emergent bilinguals first try to communicate in their new language, they often invent structures or words based on what they know about the language. For example, many students learning Spanish use Yo gusto instead of the irregular, con- ventional form, Me gusta, for I like. Since other verbs add o to form the first-person singular, they invent forms like Yo gusto. As they interact with more proficient speak- ers, they begin to notice the conventional form, Me gusta, and then they modify their personal invention to conform to the conventional Spanish form. Selinker (1972) explains that in the process of acquiring a language, learners go through several gradual approximations that move them from their home language to their new language through a series of what he calls interlanguages. These interlan- guages are their personal inventions. Over time, these inventions come closer to the conventional forms of the language they are acquiring. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Think of an example in your own language learning or your students' oral or written language development in which the personal inventions gradually approximated the social convention. Share your example. Spontaneous and Scientific Concepts A second important theoretical construct that Vygotsky developed was the distinc- tion between spontaneous and scientific concepts. Spontaneous concepts are ideas we develop fairly directly from everyday experience. For example, we know what car means if we live in a society in which people drive cars. We develop the concept for car by riding in cars and seeing cars. The word car becomes a label we can use to talk about this concept. We acquire spontaneous concepts without any special help. They are simply part of our daily lives. Scientific concepts, on the other hand, are abstract ideas that societies use to organize and categorize experiences. The concept of transportation, for example, is a scientific concept. We use this term to categorize a number of different means of conveyance, whether the mode be a car, a bus, a boat, or an airplane. Children do not acquire scientific concepts from exposure to everyday events. Most often, they learn them in school. The ideas of spontaneous and scientific concepts are important in two ways when we apply them to language learning. Krashen (1982) makes an important distinction between acquiring a language and learning one. He argues that we acquire a language in the course of daily living and without much conscious awareness of the process itself. We acquire both spontaneous concepts and the language we need to commu- nicate them. On the other hand, if we study a language in school, we usually learn scientific concepts, such as verb and present tense, which we can use to categorize aspects of the language. As Krashen points out, acquisition allows us to use language to com- municate, while learning gives us abstract terms, the scientific language and concepts to talk about language. Similarly, Cummins (2000) makes a distinction between conversational language and academic language. Conversational language is what we use to communicate spontaneous concepts and talk about daily events. In contrast, academic language involves the use of terms and language forms we use to communicate scientific concepts that we study in school. This distinction is important for teachers work- ing with emergent bilinguals. As Cummins points out, students may appear to have developed a high level of basic English communicative proficiency but still struggle with grade-level academic work. This is because they have not yet acquired the sci- entific concepts and language needed in school even though they can communicate in English with teachers and other students. What they need is greater exposure to the academic register, both oral and written, that occurs as students read, write, and discuss school subjects. They can acquire the concepts and the vocabulary used in academic language in school in the same way they acquire conversational language outside school settings. Surez-Orozco and Marks explain that less-developed academic English profi- ciency can mask the actual knowledge and skills of immigrant second language learners (SLLs), which they are unable to express and demonstrate (2016, 114). They go on to explain that even when they seem to be able to participate, students whose English is just developing often read more slowly and struggle with the language and cultural knowledge native-born middle-class students have (114). Emergent bilinguals who lack academic language have lower standardized test scores, get lower GPAs, repeat grades more often, and generally have lower graduation rates. Surez- Orozco reports: Scholarly research has shown a high correlation between proficiency in academic language skills and academic achievement (2018, 6). REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Vygotsky's distinction between spontaneous concepts and scientific concepts extends to the language needed to communicate those concepts. Conversational language reflects spontaneous concepts, while academic language reflects scientific language. Think of some ways you or another teacher could help students move from using conversational language to using academic language. Share specific examples. Language Acquisition As students develop their first and additional languages, they develop different types and levels of language. It is helpful to consider the main types of competence needed to communicate in settings in and out of schools. Grammatical Competence Grammatical competence is knowledge of a language that allows us to get and give information about the world. Linguists use the term grammatical to refer to an ability to use the grammatical forms and structures of a language to communicate. It does not refer to consciously knowing the scientific language of forms and structures or to what most educators mean when they teach grammar in English classes. We can communi- cate in a language without knowing that the word is a noun or whether a sentence is declarative or interrogative. Instead, grammatical competence allows us to say, Today is Monday, or The man chased the dog. Linguists such as Chomsky have described grammatical compe- tence. They include the following areas when they discuss grammatical competence: (1) phonology, (2) morphology, (3) syntax, and (4) semantics. Phonology refers to the sound system of a language. Each language consists of a set of sounds (phonemes) that speakers use to indicate differences in meaning among words. Developing grammatical competence involves learning which sounds in a language make a difference in meaning and being able to distinguish and produce those sounds. So, for example, native speakers of English can recognize the dif- ference in meaning between cat and hat because of the difference in the phonemes represented by the letters c and h. Phonology also includes other areas, such as into- nation and stress. Morphology is our knowledge of the structure of words. It involves knowing which prefixes or suffixes can be added to a root or base form. We add -ed to some verbs to make them past tense, for example. English morphology is fairly simple compared with that of other languages. English relies more on the order of the words (the syntax) than on prefixes and suffixes. Languages such as Turkish, on the other hand, have complex morphology, but there are fewer restrictions on the order of the words. Syntax is the area most linguists working in English have focused on, since English relies heavily on the order of words to convey meanings. We know that there is a big difference between The man chased the dog and The dog chased the man. This difference in meaning depends on the order of the words. Syntax is a study of the acquired rules that native speakers use to combine words into sentences. Semantics is a fourth aspect of grammatical competence. Semantics has to do with word meanings. If we know English, we know that dog refers to a particular kind of animal, and cat refers to a different kind of animal. Meanings can be complex. Both dog and cat can have secondary meanings. You can dog it at work, and someone can be catty. a Semantics also has to do with the knowledge of words that commonly go together or collocate. Words like dog and cat are usually associated with other words referring to animals that are pets. Words like boat might be connected with water and lake. We organize concepts into categories and use different terms to refer to more general or more specific ideas within the categories. Cook is a general term and bake and roast are more specific. The three words are in the same semantic field. Grammatical compe- tence involves a knowledge of how such fields are organized. This is a very brief overview of some of the aspects of grammatical competence. We simply want to give you some idea of the kinds of knowledge speakers acquire as they develop proficiency in a language. In order to get and give basic information, speakers need phonological, morphological, syntactic, and semantic knowledge. That's what we all acquire as we develop our home language, and it's what English learners need to develop as they acquire English. Grammatical competence allows us to talk about the world, but we need more than grammatical competence to function effec- tively in a new language. Communicative Competence A second kind of competence that language learners need to function in a new lan- guage and culture is communicative competence. Hymes (1970) defines communica- tive competence as knowing what to say to whom, when, and in what circumstances. Linguists often refer to this as pragmatics. Acquiring a language, then, involves more than developing grammatical competence. Learners must also develop the knowledge of how to use the language appropriately in different contexts. The norms for com- municative competence vary from one linguistic and sociocultural group to another and from one context to another, and part of what we acquire when we acquire a language is the ability to function effectively in different settings. Often, second lan- guage learners have developed grammatical competence but still lack communicative competence. We became more aware of the importance of helping students develop communi- cative competence while living in Venezuela. Both of us speak Spanish well enough to communicate (we have grammatical competence), but at times we found ourselves lacking in communicative competence. For example, in Mrida there is a very popular bakery where many people go to get fresh breads, rolls, and pastries. At certain times of the day, the long counter of the bakery is crowded with people two or three rows deep. We found ourselves avoiding these busy times because we had trouble getting the attention of the clerks. The orderly rules for taking turns that apply in the United States didn't apply at this bakery. On one occasion Yvonne waited helplessly for twenty minutes as people came, called out their orders to the clerks, and left with their purchases. Finally, a man noticed how long she had been standing there, and he called to the clerk to help the seora. Yvonne knew what words to useshe could understand the Spanishbut she simply could not call out her order like all the Venezuelans who preceded her. She didn't want to appear rude, but what is interpreted as overly aggressive behavior in one country may be the norm in another. Yvonne lacked the communicative competence needed to buy bread in that situation. Communicative competence is the ability to say the right thing in different social situations. This is hard enough in one's home language and developing communica- tive competence in a new language is even more difficult. A professor friend of ours from Venezuela came to study with us in California. We took trips with her along the coast and to Yosemite with the dean of our graduate school and his wife. Both the dean and his wife are very religious people and also very proper. Even though the car trips were contexts for casual conversation, we maintained a fairly formal style of speech. Our Venezuelan friend spoke excellent English, but she had not yet acquired some of the nuances needed for effective communication. As we drove into Yosemite National Park, she was very impressed with the views and continually exclaimed, "Oh, my God! That's so beautiful! In Spanish, Dios mo (my God) is a very common expression that carries little emotional impact, but in English it is a much stronger expression and one we would not have used with the dean and his wife. Coming from this sophisticated professor in that company, the words sounded completely inappro- priate. In other settings with other people, there would be nothing unusual about her words. One of the problems for second language learners is that teachers will seldom explain sociolinguistic gaffes. Instead, they respond to the inappropriate behavior as a discipline problem or ignore it because they do not know how to explain it. However, students benefit when teachers recognize their actual intent and help them develop the communicative competence they lack instead of disciplining them for poor behavior or ignoring these gaffes. Johnson (1995) points out that one specific social context in which our students need to function is the classroom. Classrooms have very clear (if typically unstated) rules that govern topics for conversation and writing and roles for participants in communicative exchanges. What students need, according to Johnson, is classroom communicative competence, which she defines as the knowledge and competencies that second language students need in order to participate in, learn from, and acquire a second language in the classroom (160). Teachers can help students acquire a new language by making the rules for classroom interactions explicit. For example, communicative competence involves learning how to enter a conver- sation or to end one. In our home language, we have acquired the rules for contribut- ing to an ongoing discussion. However, English language learners often have trouble knowing when to add to a classroom discussion. They may jump in at what seems to be an inappropriate time, or they may remain silent, even when called on. Classroom discussions may be particularly difficult if students have had previous schooling other countries where the unwritten rules for discussion were quite different from the rules in their new country. Teachers can help students by setting some guidelines for classroom conversations and small-group discussions. We have seen teachers do this effectively when they organize literature studies or guided reading or writing instruc- tion. The point is that teachers need to teach communicative competence explicitly by explaining the norms for classroom communication. Communicative competence is often thought of as the knowledge to use oral lan- guage in ways that are appropriate to different social settings. However, communica- tive competence includes the ability to use language effectively in any mode. School content areas have both oral and written language norms. In general, the spoken (or signed) and written language have properties of academic language (Schleppegrell 2004). This register is more formal and abstract. In addition, academic language varies from one subject to another. A book report in language arts and a science report are organized differently and use a different style and vocabulary (Freeman and Free- man 2009). REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Think of a time you or one of your emergent bilingual student's communicative competence did not match their grammatical competence. In other words, a time when they said or wrote something using conventional language in the wrong context. Share your example. Competence and Performance Another distinction that is important for determining an emergent bilingual's lan- guage proficiency in school is the difference between competence and performance. As Chomsky (1975) explains, competence in a language is how well a person can communicate in that language under the best conditions. Our competence repre- sents a kind of idealized best ability. In contrast, our performance represents how well we use language in a particular situation. As we all know, our performance seldom matches our competence. In most situations, we don't perform up to our full ability. We may be nervous, tired, bored, or simply careless. The competence is important for teachers trying to determine how proficient a student is. We should remember that a student's actual performance may a concept of not fully show their underlying competence. For example, ten-year-old Alfredo, educated in both Mexico and the United States, understands, speaks, reads, and writes English well despite having an accent. When he arrived at a new school, his teacher first tried to engage him in friendly conversation and then called on him to answer questions. He responded haltingly because he was nervous and was unaccustomed to the informal classroom atmosphere. Based on his performance, his teacher assumed Alfredo understood and spoke very little English. Actually, Alfredo's competence in English was much greater than his performance suggested. Competence and Correctness People acquire competence in one or more languages, but their ability to produce and comprehend a language or languages is not the same as their ability to use conven- tional or standard forms of the languages. The competence we are describing is not the kind of conscious knowledge usually associated with school grammar lessons. It is not the ability to put commas in the right places or to use different from rather than different than. Those are matters of usage and are typically associated with standard written language and are generally acquired when students receive feedback on their language use during class discussions and in the editing stage of process writing. The feedback is most effective when it is presented as a way to communicate important ideas more effectively. Many teachers do this through minilessons on particular points that several students may be having trouble with, such as writing complete sentences or avoiding run-on sentences. Competence and Learner Strategies Teachers can also encourage individual language learners to use some specific strate- gies to communicate in their new language. In order to acquire a language, students need to use it, so these strategies are designed to engage language learners who might otherwise remain passive and unengaged. Canale and Swain refer to this as helping students develop strategic competence, which they define as the verbal and nonverbal communication strategies that may be called into action to compensate for break- downs in communication due to performance variables or due to insufficient com- petence (1980, 30). Teachers can help English learners acquire English by making them aware of these strategies and encouraging their use. As long as English learners are active participants in classroom discussions and small-group activities, they will continue to acquire grammatical and communicative competence. There are several learner strategies students can use. One is to use nonverbal strate- gies, a kind of charade, such as spreading your hands apart to indicate big." Students can also use different verbal strategies to express meanings. One strategy is to make up (coin) a word to describe something in hopes that the person they are talking to will supply the target-language word. Wells and Chang-Wells (1992) recorded a conver- sation in which Marilda employed this strategy by coining the word windfinder for weather vane. A teacher we work with reported that one of her English language learn- ers asked if she could use the pencil fixer. The teacher realized her student needed to use the pencil sharpener. Language learners may also paraphrase, using a word or phrase that they hope is equivalent to the word they lack. When Christa, a student teacher, interviewed Moua for her case stud the Hmong student explained that his dad puts in wind makers ... cold wind makers for a living. After a bit of probing, Christa figured out that Moua's father installs air conditioners. By using paraphrase, Moua was able to get his message across. Another teacher wrote about how her student used paraphrase. A small group of students was reading a book about what some children gave their mother for her birthday. The text did not name the gift, but the last page contained a colorful picture of a flower vase. One of the boys in the reading group asked, What is that thing that you use to put flowers into?" This paraphrase allowed the teacher to help him find the word he wanted. In addition to using paraphrase for specific words, an English learner a literal translation and apply the structure of their home language to their new language. For example, in Spanish adjectives usually follow nouns while in English adjectives generally precede nouns. As a result, a Spanish speaker may use a struc- ture such as a car red rather than the standard English form, a red car. However, over time with exposure to English, most emergent bilinguals acquire the conven- tional English syntax. If a person is studying a language related to their native language, a good strategy is to use cognates. English and Spanish, for example, have many words in common derived from Latin roots. For instance, the Spanish noun parque is a cognate for park in English. Emergent bilinguals can access cognates when they come across an unknown word during reading, if they stop to think whether it looks or sounds like a word they know in their native language. This is especially helpful in science, since for many scientific terms, such as ecology and photosynthesis, the English and Spanish are spelled almost the same. However, cognates also exist in other content areas, like social stud- ies, where words like government and contract are very similar in the two languages. may use Teachers can find an extensive list of cognates at the Colorn Colorado website, www .colorincolorado.org. A very common strategy that many second language learners use is to assume that the language they are learning is completely regular. Children use this strategy naturally as they acquire their home language. They overgeneralize a rule and apply it to a word that does not follow the pattern. For example, English-speaking children at a certain stage will often use a past-tense form like goed because they assume that all verbs form the past tense the same way. English learners use the same strategy. Moua used the word becomed as he talked with Christa. He also used golds for the plural of gold, overgeneralizing the rule for forming plurals. Even though the forms may not be correct, they enable the English learner to communicate. A more direct strategy many students develop is to simply ask, How do you say... ? In fact, this is a handy phrase that most teachers give their students early in a language course. This strategy works very well in a language class in which the teacher is bilingual. It doesn't work as well in a setting in which the teacher and the other students don't speak both languages. If a Spanish speaker asks, How do you say pensar in English? someone needs to be able to translate pensar from Spanish to English in order to answer the question. This is more difficult with less common lan- guages, such as Basque. The other problem with using this strategy too much is that it interrupts the flow of conversation more than the other strategies we have described, and students may come to rely too heavily on this one strategy rather than use a vari- ety of strategies. One strategy language learners often adopt, avoidance, is not productive. When specific strategies fail, language learners may simply avoid using a word, structure, or topic. For example, they may avoid a topic because they don't feel competent to talk about it in the target language, or they may stop in the middle of an ex- planation or story because the linguistic demands are simply too great. For this reason, the key is for teachers to scaffold language instruction to ensure students stay engaged. Students cannot acquire a language if they avoid communicating in that language. Fillmore (1991, as cited in Grosjean 2010) reports that the successful second lan- guage learners she studied relied on three strategies in using their new language: (1) Join a group and act as if you know what is going on, even if you don't; (2) give the impression, with a few well-chosen words, that you can speak the language; and, (3) count on your friends for help. (187) By using these three general strategies, the good language learners were more fully involved in using the new language, and, in the process, they acquired the language. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK What strategies have you used to communicate in a language you were acquiring? What strategies do your emergent bilinguals use? First and Second Language Acquisition: Becoming Bilingual Nearly all humans develop a home language, and many develop additional languages. This raises the question of whether second language acquisition is different in some fundamental way from first language acquisition. For example, some researchers have argued that a first language is acquired, that is, it is picked up naturally without instruction, but second languages must be learned in the same way we learn history or biology. However, other researchers claim that humans can acquire multiple languages, and the number of bi- and multilingual people in the world suggests that people can acquire more than one language. Baker writes, Children are born ready to become bilinguals, trilinguals, multilinguals (2006, 116). Simultaneous and Sequential Bilingualism Baker (2006) distinguishes between two types of childhood bilingualism. When a child acquires two languages at the same time from birth or early childhood, this is referred to as simultaneous childhood bilingualism or infant bilingualism. Wang and other researchers have come to refer to this process as multilingual first language acquisition (Wang 2015). Researchers have noticed differences between language acquisition in young chil- dren up to about age five and acquisition in older learners. Studies have shown that brain lateralization occurs at about age five (Brown 2007). These first five years are a seen as the optimal period for the acquisition of one or more languages. Wang states: It seems that the peak of language acquisition begins shortly before the age of 2 years, and the gradual decline sets in before the age of 5 (2015, 115). This period, which other researchers often extend to about age twelve, is often referred to as a critical or sensitive period for language acquisition. A more common scenario is sequential bilingualism, when children learn one lan- guage at home and then another language in preschool or elementary school. Studies of individual bilinguals show that the process of second language acquisition is like first language acquisition. The keys to acquiring a second language are regular contact with people who speak another language and a need to communicate with them. When those conditions are met, people acquire additional languages. Older language learners can attain high levels of proficiency in one or more lan- guages, so the idea of a biological period may be less important than the quality and quantity of input in an additional language. There is no clear evidence that the process of acquiring additional languages is different from the process of the initial language acquisition. The factors that help account for acquisition are both social and biological. Language develops in response to a need to communicate, and humans seem to have an ability to acquire additional languages when they have a need and interact with us- ers of the other language or languages, including oral or signed and written. As emergent bilinguals begin school, the kind of input they receive changes. They continue to interact with parents, community members, and peers at school in their home language(s). However, at the same time, they interact with teachers and other adults who may use not only a different language, English, but also different registers of language including the academic registers of the various subject areas. In this pro- cess, they also develop the scientific language of the disciplines. As English learners get older, they may suffer some attrition of their home lan- guage. These students who enter school speaking a language other than English may leave school speaking primarily English. The long-term English learners we described in Chapter 2 fall into this category. This occurs as students spend more time commu- nicating in the new language and less time communicating in the home language. In addition, if society values English more than the home language, LTELs often avoid using the home language. Some older students may reach a stage at which they have developed enough proficiency in English that they hit a sort of plateau as their English stabilizes, and they do not seem to acquire more complex English or they maintain some accent. Previously, scholars referred to this as fossilization, but stabilization better describes this phenomenon. As this shows, language develops to meet communicative needs, and when a certain language is not needed, it stops developing. Unfortunately, this process of natural language acquisition does not usually oc- cur in most foreign language classes. Students studying another language in a foreign language class are not in regular contact with native speakers of the target language except for their teacher, and they do not have a need to communicate in that language other than to pass the class. That is why in many classes foreign languages are learned the same way other school subjects are learned instead of being acquired the way languages are naturally acquired. This is also because the focus is often on the forms of the language, that is, aspects of language such as verb tenses and sentence structures. a Theory and Research Research in second language acquisition can contribute to a theory of SLA. Examples of research would be a study of the natural order of acquisition of morphemes or a study of the relationship between intelligence and language aptitude. A theoreti- cal researcher, for example, might develop a theory that the effects of reading in the second language will be reflected in students' second language writing. The researcher might then look at the writing of second language learners for evidence of the effects of reading Research always supports credible theories. However, attempts to apply research di- rectly to practice have not been productive. In his own research into the acquisition of morphemes by second language students, Krashen found that certain morphemes were acquired earlier than others. Morphemes are the smallest parts of words that carry meaning. So, for example, in the word unties there are three morphemes: the prefix un, the base tie, and the suffix s. In English the morpheme s that indicates the plural in a word like toys is acquired at an earlier age than the third-person s in a word like unties (He unties his shoes). Krashen maintains that research findings such as these cannot be directly applied to practice. As he himself says, I made this error several years ago when I suggested that the natural order of acquisition become the new grammatical syllabus (1985, 47). He realized that he could not use the research to design a grammar textbook with a lesson on the plural s before a lesson on the third-person s. In the first place, different students would acquire the morphemes at different times. The whole class would not be ready to acquire a certain morpheme on a certain day any more than a whole class would be ready to write a complete sentence on the a same day. In the second place, while linguists know something about the natural order of morpheme acquisition, there is much more to English grammar than morphemes, and linguists have not charted the acquisition of all the complex structures of English or any other language. Krashen's research helped him develop a theory of SLA that downplays the direct teaching of grammar. Krashen points out that SLA theory acts to mediate between research and practice. Teachers can benefit from their understanding of theory in their daily teaching practice. Krashen asserts, Methodologists are missing a rich source of information ... if they neglect theory (48), and without theory, there is no way to distinguish effective teaching procedures from ritual, no way to determine which aspects of a method are and are not helpful (1985, 52). A knowledge of SLA theory, then, allows a teacher to reflect on and to refine day-to-day practice. A teacher with an understanding of language acquisition can better evaluate different curriculum op- tions or specific strategies and programs. With that view in mind, we describe Krash- en's theory of second language acquisition. Krashen's Theory of Second Language Acquisition We have looked generally at how learning takes place, and we have also considered the kinds of competence emergent bilinguals acquire when they acquire an addi- tional language. We now examine Krashen's theory of second language acquisition. Krashen's monitor model consists of five interrelated hypotheses: (1) the acquisition versus learning hypothesis, (2) the natural order hypothesis, (3) the monitor hypoth- esis, (4) the input hypothesis, and (5) the affective filter hypothesis. In the follow- ing sections, we explain each hypothesis and provide examples. The monitor model emphasizes the role of comprehensible input in language acquisition, and it is based on Chomsky's theory of linguistics. The Acquisition Versus Learning Hypothesis Krashen begins by making an important distinction between two ways of developing a new language. The first of these is acquisition. According to Krashen we acquire a new language subconsciously as we receive messages we understand. For example, if we are living in a foreign country and go to the store to buy food, we may acquire new vocabulary or syntactic structures in the process of trying to understand what the clerk is saying. We are not focused on the language. Rather, we are using the language for real purposes, and acquisition occurs naturally as we attempt to conduct our business. Yvonne remembers learning the names of fruits in the market in Venezuela. She would point to the type of fruit she wanted and then discuss whether a specific fruit was at the perfect point of maturation with the vendor. She learned to insist that her papayas were ripe but not spoiled and tell the vendor she wouldn't buy from him next time if he didn't pick out a perfect one for her. Acquisition can also occur in classrooms in which teachers engage students in authentic communicative experiences. For example, if students work in pairs to read and solve a math word problem, in the process of discussing a solution both students begin to acquire the academic language related to math, such as greater than and less than, subtract, and add. They also may acquire syntactic structures including questions beginning with subordinate clauses, such as If Juan has twenty-five marbles and gives ten to Bill, how many marbles does Juan have left? Krashen (2004, 2013) has also shown that we can acquire language as we read. In fact, since people are able to read more rapidly than they speak, written language is a better source for acquisition than oral language. In addition, reading provides the input students need to acquire academic language since written language has more of the characteristics of academic language than does spoken language (Biber 1986; Hal- liday 1989). Krashen contrasts acquisition with learning. Learning is a conscious process in which we focus on various aspects of the language itself. It is what generally occurs in classrooms when teachers divide language up into chunks, present one chunk at a time, and provide students with feedback to indicate how well they have mastered the various aspects of language that have been taught. A teacher might present a lesson on regular verbs in the past tense, for example, giving attention to the ed that we add to the verb in sentences, such as He played chess yesterday. It is this structure that students are expected to learn. Learning is associated with classroom instruction and is usually tested. Although Krashen's theory focuses on individual psychological factors involved in second language acquisition, Gee offers a definition of acquisition that expands on Krashen's by including a social component: Acquisition is a process of acquiring something subconsciously by exposure to models, a process of trial and error, and practice within social groups, without formal teaching. It happens in natural settings that are meaningful and functional in the sense that acquirers know that they need to acquire the thing they are exposed to in order to function and that they in fact want to so function. (1992, 113) For example, teenagers pay close attention to how their peers dress. They acquire a knowledge of current clothing styles that are appropriate in different settings. In the 1950s girls wore poodle skirts and currently they may wear jeans with rips and tears. No one teaches them how to choose the clothing. This expanded definition of acquisition brings an important social element into the distinction between acquisition and learning. Acquisition occurs in social contexts as people attempt to communicate with others. When the context of learning is a social studies class, students acquire this register of academic language as they acquire knowledge of social studies. It appears that acquisition and learning lead to different kinds of abilities. As Gee puts it, we are better at performing what we acquire, but we consciously know more about what we have learned (1992, 114). In the case of second languages, acquisition allows us to speak and understand, read and write the language. Learning allows us to talk about (or pass exams on) the language. Many adults who have studied a foreign language in high school or college and received high grades never developed the abil- ity to speak or understand the language they studied. Their performance on grammar and vocabulary tests determined their grades. Yvonne's experience with studying French in college certainly demonstrates this. She took four years of French, could translate French into English quite well, and knew French grammar. Her grades were always very high in the courses she took. However, her ability to communicate in French is severely limited. Recently, when Yvonne and David were in Costa Rica staying at a remote inn, the only other guests were from Paris. Although Yvonne had studied French extensively, she struggled to understand simple conversation and communicate basic ideas. A good example of the acquisition versus learning distinction comes from the experiences of Jos Luis, Guillermo, and Patricia, whom we discussed in Chapter 2. The teens studied English in El Salvador. This was a case of learning the rules and structures of the language. When they came to the United States, they did know some English, but it was very limited. In their new home in Tucson, they were immersed in English and began to acquire the language as they used it daily. Krashen argues that children acquire (they don't learn) their first language(s) as they use language to communicate and to make sense of the world. Krashen claims that both children and adults have the capacity to acquire additional languages because a they possess what Chomsky (1975) calls a universal grammar, a mental ability to ac- quire language. Krashen claims that acquisition accounts for almost all of our language development and that learning plays a minimal role. Second language classrooms should be places for acquisition, but more often second and foreign language teachers focus on learning When teaching Spanish, Yvonne, like many foreign language teachers, worried that students needed to learn the grammar, because that is what the department tested. At the beginning of the course, she explained the difference between acquisition and learning to her students in Spanish 1 and Spanish 2. She suggested students study the grammar in the books at home and take advantage of classroom time for language acquisition. She organized activities to help her students develop Spanish proficiency by talking, reading, and writing about current events and topics related to their lives. Discussions of music and television programs involved her students in using language for authentic purposes, and they acquired language as they used it. Yvonne ensured that the conver- sations included the grammar points and structures in the textbook grammar lessons but were put into an engaging context. So, for example, students used the past tense to describe what had happened in a movie or in a current event. Yvonne had departed from traditional approaches to engage her students and to change her classroom from a place for learning to a setting for acquisition. This required careful planning and a search for materials in Spanish that included current events and trends in society. At the end of the semester, students were able to pass the level exams despite the limited time spent in class on the teaching of grammar. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK If you studied a foreign language in high school or college, did your teacher use a method that emphasized acquisition or learning? Did you develop proficiency in the language? If you are bilingual or multilingual, how did you develop your additional language or languages? Was it through learning or acquisition? Discuss this with others and consider how your experiences affect your teaching of emergent bilinguals. The Natural Order Hypothesis Krashen's second hypothesis is that language is acquired in a natural order. Some aspects of a language are developed earlier than others. For example, the ing mor- pheme added to a word like run to form running comes earlier than the possessive s added to the word John in John's book. Most parents are aware that phonemes like /p/ and /m/ are acquired earlier than others, like /r/. That's why English-speaking parents are often called Papa or Mama by babies, not Roro. In the area of syntax, state- ments generally precede questions. Children do not acquire the structure of questions early, so they often use statement structures such as I go store, too? or You like teddy? to pose questions. Krashen points out that all learners of a particular language, such as English, seem to acquire the language in the same order no matter what their home language may be. Krashen bases this hypothesis on studies carried out by Dulay and Burt (1974). These researchers collected samples of speech from Chinese- and Spanish-speaking students acquiring English. They found that both groups acquired English morphemes in about the same order. They found, for example, that students acquired the articles such as a and the before they acquired the regular past tense ed. These early studies were subsequently confirmed by the work of a number of other researchers. The natural order applies to language that is acquired, not language that is learned. In fact, students may be asked to learn aspects of language before they are ready to ac- quire them. The result may be good performance of the items on a test but inability to use the same items in a natural setting. During grammar tests, students' performance may exceed their competence. In teaching Spanish, Yvonne found that the expression for like in Spanish was a late-acquired item. In Spanish, I like is Me gusta (It is pleasing to me). If the things I like are plural, I say Me gustan (They are pleasing to me). This structure caused no end of confusion for Yvonne's beginning students. She worked with them diligently, explaining how the structure worked and giving examples. Even those who did well on the department test had not acquired the structure. When Yvonne asked her stu- dents to evaluate the course in their daily diary at the end of the semester, almost all the students incorrectly wrote Yo gusto for I like. They knew that yo meant I and knew the verb gustar was to like. So they simply conjugated the verb as a regular verb despite the emphasis on learning the expression Me gusta. Most books used in language courses present grammar in a certain order, but since linguists have only a rudimentary understanding of the complete order of acquisition of phonemes, morphemes, syntax, and so on, no book can be written that can claim to mirror the natural order. Even if such a book were written, students would invari- ably be at different stages, and in a class of thirty students, no grammar lesson would be appropriate for everyone. Krashen, however, points out that if a teacher focuses on acquisition activities, rather than trying to get students to learn certain grammatical points, all students will acquire the aspects of a language that they are developmentally ready to acquire in a natural order. The rate of acquisition of morphemes and struc- tures will vary for different students, but the order will be the same. The Monitor Hypothesis The monitor hypothesis helps explain the different functions that acquisition and learning play. Acquisition results in developing the phonology, vocabulary, and syntax that we can draw on to produce and comprehend a new language. Without acquisi- tion, we could not understand or produce anything other than limited aspects of the language we have learned. Learning, on the other hand, provides us with rules we can use to monitor our output as we speak or write. The monitor is like an editor, check- ing what we produce. The monitor can operate when we have time, when we focus on grammatical form, and when we know the rules. Yvonne applied her monitor during her oral exams for her doctorate. Her com- mittee of five had asked her several questions in English about language acquisition and bilingual education that she had answered fairly comfortably. Then, one of her committee members asked a question in Spanish, a clear suggestion that Yvonne should also answer in Spanish. Her most vivid memory of the incident was how much she was checking to be sure her Spanish was correcthow much she was ap- plying her monitor. In particular, she was careful to watch for the correct use of the subjunctive mood, verb endings, and adjective agreement, all aspects of Spanish that she had learned and had not fully acquired. In this situation, Yv