Question: QUESTION 1) Imagine that an OD consultant was going to conduct an intervention in an organization you know well. Of the Process Variables (Figure 14.1)

QUESTION 1) Imagine that an OD consultant was going to conduct an intervention in an organization you know well. Of the Process Variables (Figure 14.1) and Outcome Variables (Figure 14.2) in Organization Development Evaluation in Chapter 14 of your textbook, what outcome or process variables would you use to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention?

QUESTION 2) Of the challenges discussed in Chapter 16 of the textbook, what challenge do you think will be the most prominent you will face in your career? What will be the implications - both positive and negative - for organizations and the people in them? Why do you think so?

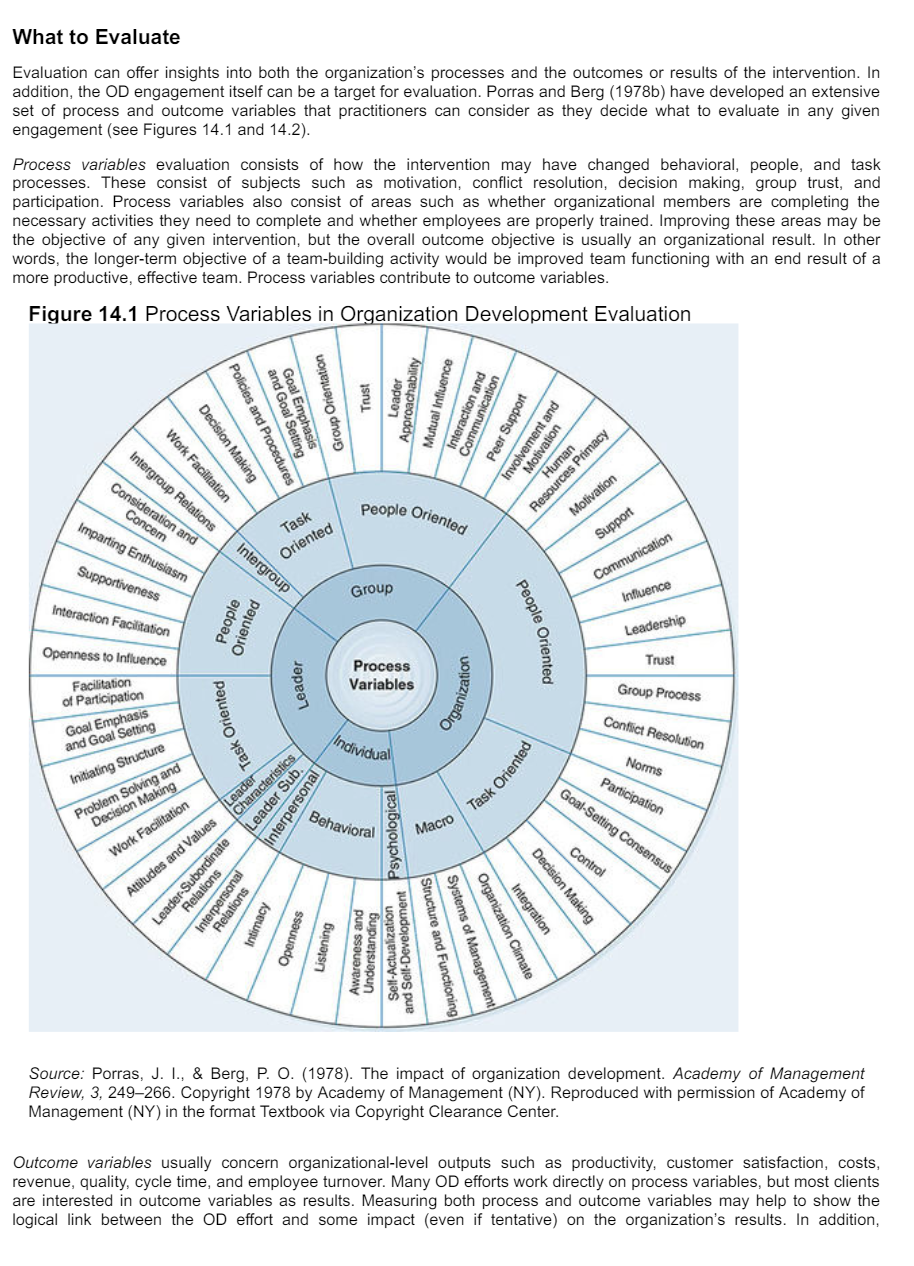

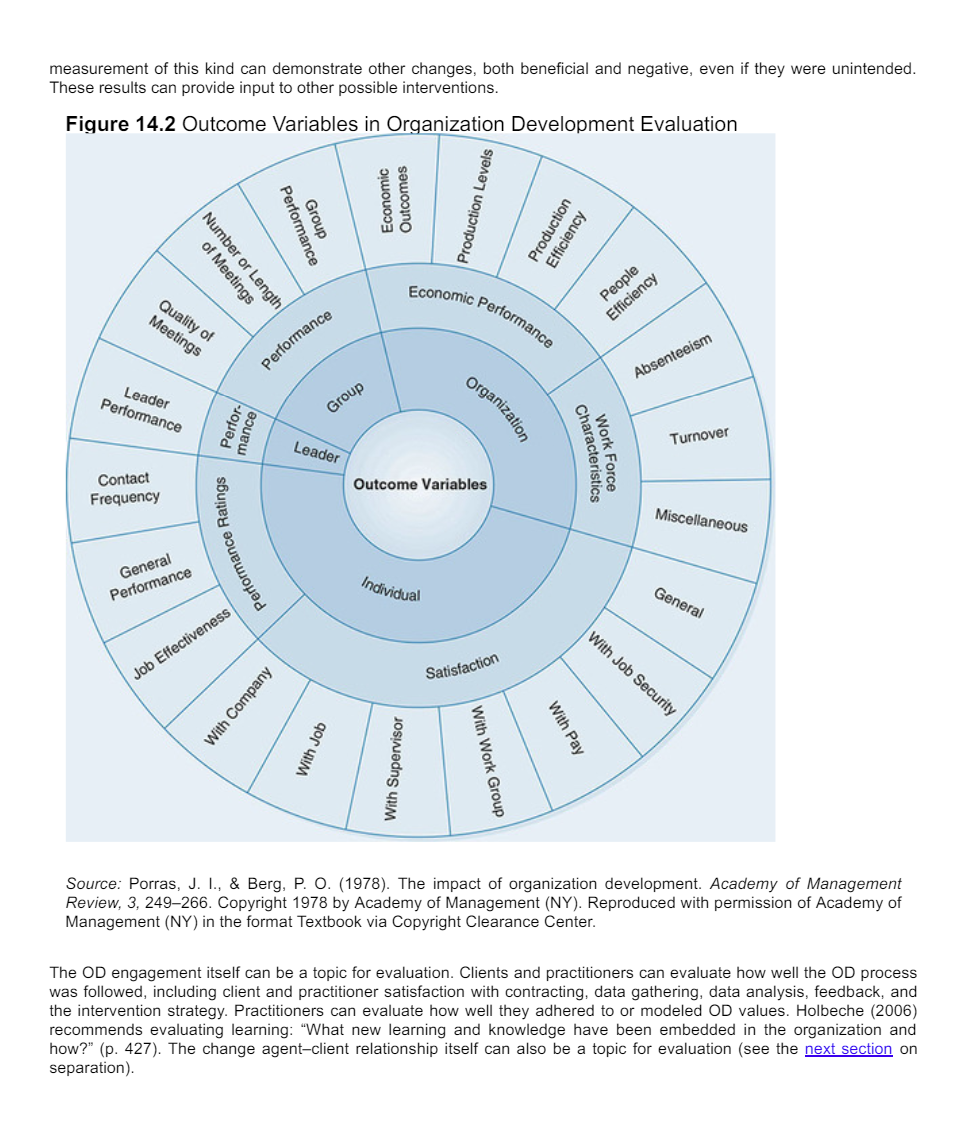

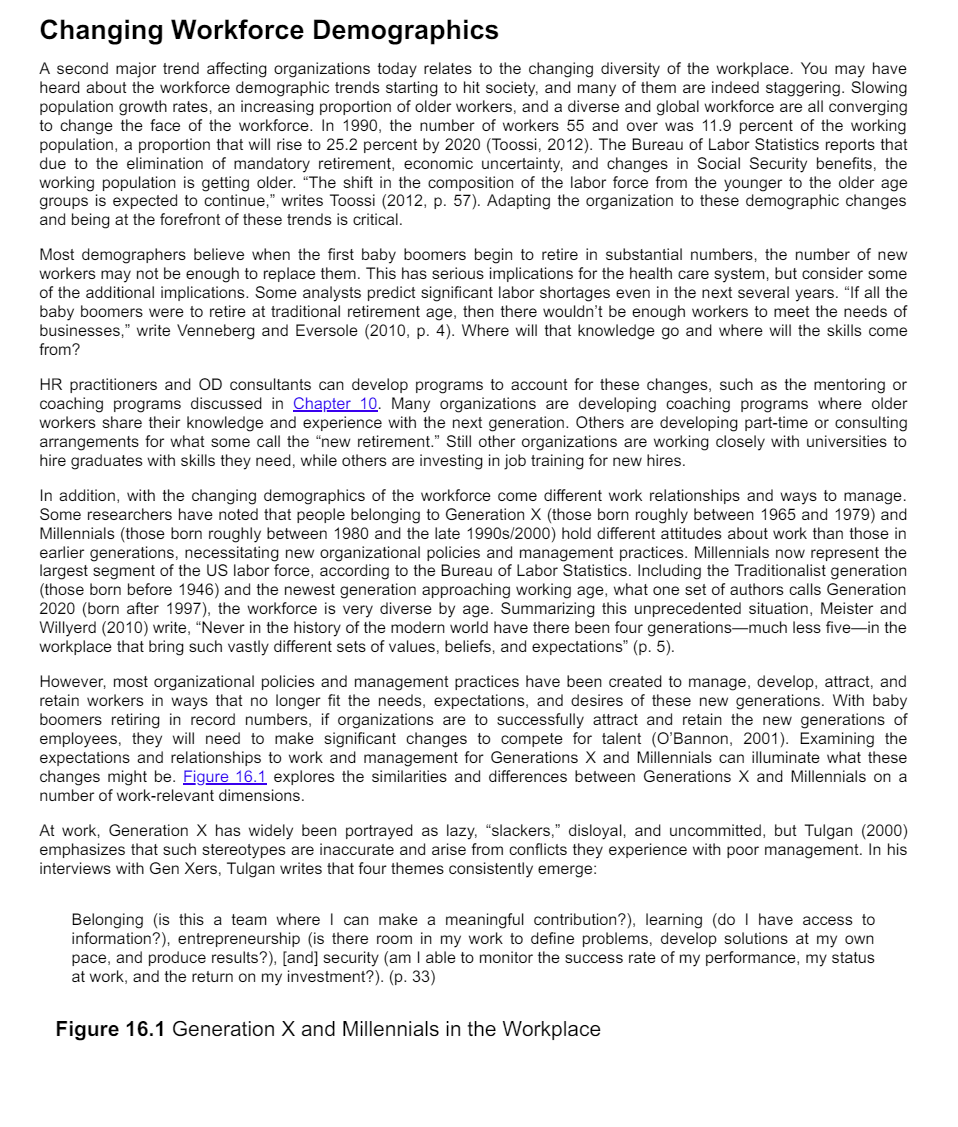

What to Evaluate Evaluation can offer insights into both the organization's processes and the outcomes or results of the intervention. In addition, the OD engagement itself can be a target for evaluation. Porras and Berg (1978b) have developed an extensive set of process and outcome variables that practitioners can consider as they decide what to evaluate in any given engagement (see Figures 14.1 and 14.2). Process variables evaluation consists of how the intervention may have changed behavioral, people, and task processes. These consist of subjects such as motivation, conflict resolution, decision making, group trust, and participation. Process variables also consist of areas such as whether organizational members are completing the necessary activities they need to complete and whether employees are properly trained. Improving these areas may be the objective of any given intervention, but the overall outcome objective is usually an organizational result. In other words, the longer-term objective of a team-building activity would be improved team functioning with an end result of a more productive, effective team. Process variables contribute to outcome variables. Figure 14.1 Process Variables in Organization Development Evaluation Trust Leader Approachability Group Orientation Mutual Influence Goal Emphasis Interaction and and Goal Setting Communication Policies and Procedures Peer Support Decision Making Involvement and Motivation Work Facilitation Human Resources Primacy Intergroup Relations Motivation Consideration and Concem Task People Oriented Support Oriented Imparting Enthusiasm Communication Intergroup Supportiveness Group nfluence Interaction Facilitation People Oriented People Oriented Leadership Openness to Influence Process Trust Facilitation Leader Variables of Participation Organization Group Process Goal Emphasis Task Oriented and Goal Setting Conflict Resolution Individual Initiating Structure acterstics ask Oriented Norms Problem Solving and Leader Decision Making Chara Leader Sub. Participation nterpersonal Work Facilitation Behavioral Macro Goal-Setting Consensus Psychological Attitudes and Values Control Leader-Subordinate Decision Making Relations interpersonal Relations Integration Intimacy Organization Climate Openness Systems of Management Listening and Sell-Development Structure and Functioning Awareness and Understanding Self-Actualization Source: Porras, J. I., & Berg, P. O. (1978). The impact of organization development. Academy of Management Review, 3, 249-266. Copyright 1978 by Academy of Management (NY). Reproduced with permission of Academy of Management (NY) in the format Textbook via Copyright Clearance Center. Outcome variables usually concern organizational-level outputs such as productivity, customer satisfaction, costs, revenue, quality, cycle time, and employee turnover. Many OD efforts work directly on process variables, but most clients are interested in outcome variables as results. Measuring both process and outcome variables may help to show the logical link between the OD effort and some impact (even if tentative) on the organization's results. In addition,measurement of this kind can demonstrate other changes, both beneficial and negative, even if they were unintended. These results can provide input to other possible interventions. Figure 14.2 Outcome Variables in Organization Development Evaluation Outcomes Economic Production Levels Group Performance Production Efficiency Number or Length of Meetings People Efficiency Quality of Economic Performance Meetings performance Absenteeism Leader Group Performance ganization Perfor- mance Turnover Leader Work Force Characteristics Contact Outcome Variables Frequency Miscellaneous Performance Ratings General Performance Individual General Job Effectiveness Satisfaction With Job Security With Company With Pay With Job With Work Group With Supervisor Source: Porras, J. I., & Berg, P. O. (1978). The impact of organization development. Academy of Management Review, 3, 249-266. Copyright 1978 by Academy of Management (NY). Reproduced with permission of Academy of Management (NY) in the format Textbook via Copyright Clearance Center. The OD engagement itself can be a topic for evaluation. Clients and practitioners can evaluate how well the OD process was followed, including client and practitioner satisfaction with contracting, data gathering, data analysis, feedback, and the intervention strategy. Practitioners can evaluate how well they adhered to or modeled OD values. Holbeche (2006) recommends evaluating learning: "What new learning and knowledge have been embedded in the organization and how?" (p. 427). The change agent-client relationship itself can also be a topic for evaluation (see the next section on separation).Changing Workforce Demographics A second major trend affecting organizations today relates to the changing diversity of the workplace. You may have heard about the workforce demographic trends starting to hit society, and many of them are indeed staggering. Slowing population growth rates, an increasing proportion of older workers, and a diverse and global workforce are all converging to change the face of the workforce. In 1990, the number of workers 55 and over was 11.9 percent of the working population, a proportion that will rise to 25.2 percent by 2020 (Toossi, 2012). The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that due to the elimination of mandatory retirement, economic uncertainty, and changes in Social Security benefits, the working population is getting older. \"The shift in the composition of the labor force from the younger to the older age groups is expected to continue,\" writes Toossi (2012, p. 57). Adapting the organization to these demographic changes and being at the forefront of these trends is critical. Most demographers believe when the first baby boomers begin to retire in substantial numbers, the number of new workers may not be enough to replace them. This has serious implications for the health care system, but consider some of the additional implications. Some analysts predict significant labor shortages even in the next several years. \"If all the baby boomers were to retire at traditional retirement age, then there wouldn't be enough workers to meet the needs of businesses,\" write Venneberg and Eversole (2010, p. 4). Where will that knowledge go and where will the skills come from? HR practitioners and OD consultants can develop programs to account for these changes, such as the mentoring or coaching programs discussed in Chapter 10. Many organizations are developing coaching programs where older workers share their knowledge and experience with the next generation. Others are developing part-time or consulting arrangements for what some call the \"new retirement.\" Still other organizations are working closely with universities to hire graduates with skills they need, while others are investing in job training for new hires. In addition, with the changing demographics of the workforce come different work relationships and ways to manage. Some researchers have noted that people belonging to Generation X (those born roughly between 1965 and 1979) and Millennials (those born roughly between 1980 and the late 1990s/2000) hold different attitudes about work than those in earlier generations, necessitating new organizational policies and management practices. Millennials now represent the largest segment of the US labor force, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Including the Traditionalist generation (those born before 1946) and the newest generation approaching working age, what one set of authors calls Generation 2020 (born after 1997), the workforce is very diverse by age. Summarizing this unprecedented situation, Meister and Willyerd (2010) write, \"Never in the history of the modern world have there been four generationsmuch less fivein the workplace that bring such vastly different sets of values, beliefs, and expectations\" (p. 5). However, most organizational policies and management practices have been created to manage, develop, attract, and retain workers in ways that no longer fit the needs, expectations, and desires of these new generations. With baby boomers retiring in record numbers, if organizations are to successfully attract and retain the new generations of employees, they will need to make significant changes to compete for talent (O'Bannon, 2001). Examining the expectations and relationships to work and management for Generations X and Millennials can illuminate what these changes might be. Eigure 16.1 explores the similarities and differences between Generations X and Millennials on a number of work-relevant dimensions. At work, Generation X has widely been portrayed as lazy, \"slackers,\" disloyal, and uncommitted, but Tulgan (2000) emphasizes that such stereotypes are inaccurate and arise from conflicts they experience with poor management. In his interviews with Gen Xers, Tulgan writes that four themes consistently emerge: Belonging (is this a team where | can make a meaningful contribution?), learning (do | have access to information?), entrepreneurship (is there room in my work to define problems, develop solutions at my own pace, and produce results?), [and] security (am | able to monitor the success rate of my performance, my status at work, and the return on my investment?). (p. 33) Figure 16.1 Generation X and Millennials in the Workplace Characteristic Millennials Birth Years Between 1965 and 1979 Between 1980 and 2000 Aftitudes toward Independent, free agent mentality = More open than Gen X to leaving if work work toward work requirements not met Desires to keep skills current Desires challenging work Strives for work-life balance Wants to meet personal goals Willing to forgo some financial Wants flexibility in work gains and status for personal ime \\y s 10 know why before tackling the job Technologically literate Continually wired and connected to digital media Aftitudes toward Would rather be left alone to Prefers a participative style of management complete tasks management Would prefer to learn just-in-time Wants to participate in decision making 28 needad Desires immediate feedback about Low confidence in leaders and performance ofganizalions Respects ability and skills over rank They value flexibility at work to the point that they will leave for jobs elsewhere when better opportunities present themselves, not expecting lifelong employment with a single company. Thus, they view themselves as \"free agents\" with the right to move as necessary to make best use of their skills in the right environment. They also value their family and free time and strive for a healthy balance with work. Financial gains are important, but Gen Xers are willing to earn less in order to maintain personal time. Generations X and Millennials share many similarities but also important differences. For example, while they were both raised close to technology, Millennials tend to be much more advanced with their knowledge of technology, spending 6 hours per day, on average, online (Eisner, 2005) and taking those skills to the workplace, where they multitask at their desks and in meetings. Millennials prize ability and skill development (rather than rank and job titles) and often seek out opportunities for learning. At work, they ask questions frequently with curiosity and a learning approach to their jobs, which can be perceived by their managers as threatening or challenging (Kehrli & Sopp, 2006). They dislike micromanagement yet value access to a manager who can provide immediate feedback and information as necessary. Jamison (2008) writes of four themes that emerge in work with Millennials: Recognize me: \"Millennial beliefs that everyone is equal and that everyone should be encouraged to embrace the differences in others . . . are beliefs that can be critically important to organizations struggling with how to leverage differences and build cultures of inclusion in which everyone feels valued.\" Include me: \"Twentysomethings were brought up to voice opinions and believe that their opinions are valued. . . . Millennials have been accustomed to being involved in decisions that affect them.\" Challenge me: \"Millennials are multi-taskers . . . [who desire] working on multiple assignments and participating in numerous projects.\" Work with me: \"Millennials . . . work, think, and create better in groups and bring a collaborative approach to projects and situations.\" (p. 56) A number of management practices are implicated in the expectations and work preferences of Generations X and Millennials. Both generations are likely to hold less loyalty to their employer than did people of previous generations, moving on quickly to new jobs when opportunities arise and the current job is no longer satisfying. Consequently, adapting management styles to their needs will encourage stronger relationships to the organization. Minimally, the work environment should be flexible and ideally virtual, making use of both generations' technological literacy. Organizationwide communications can be sent through technology with the ability to be downloaded to portable media devices. Training can be delivered through these same methods in short packets of information that can be learned quickly. Managers should design jobs that provide challenge, opportunities to genuinely contribute (rather than put in time or \"pay dues\"), opportunities to participate in decision making, and opportunities to learn. Managers can follow up with employees by inviting text messages with status updates on projects (Kehrli & Sopp, 2006). Some have noted that despite these management challenges, employees from Generation Y (Millennials) may be easier to manage than those of Generation X. \"Gen Y tends to value teamwork and fairness and is likely to be more positive than Gen X on a range of workplace issues including work-life balance, performance reviews, and availability of supervisors\" (Eisner, 2005, p. 9). Rewards such as additional time off can be valuable retention mechanisms. Last, employers would do well to consider the future workforce. Today's teenagers and those in their early 20s (now popularly called Generation Z, born roughly after 1996) have grown up in a hyperconnected world, and this experience will translate to values and expectations at work. Estimates are that Gen Z will become the dominant generation in the US waorkforce quickly since their numbers exceed those of Gen X (Morris, 2018). One study highlighted the technology expectations of Generation Z: 66 percent want the freedom to get an education anywhere on Earth, even through their phone. e 57 percent of smartphone users and 29 percent of regular cell phone users said they carry their cell phone because it is how they stay connected to their world. 59 percent want mobile access to help them organize their volunteering opportunities and corporate social responsibilities. (Meister & Willyerd, 2010, p. 53) With most Gen Zers expecting to interact with their organizations through mobile technology, organizations must consider the ways that this expectation will change the nature of work responsibilities, management, recruitment, team communication, retention, and more. To cite a final example of the changes in workforce demographics, based on the 2010 census, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that half of the nation's population growth since 1990 was due to immigration. There is increasing diversity in the U.S. workplace and an increasing trend toward global teams and virtual teams. Local and global workforce diversity must prompt organizations to take seriously the need for training and dialogue to develop understanding among people of different backgrounds. Diverse organizations contain the seeds of diverse ideas, and when these ideas have an opportunity to be surfaced and are considered seriously, the organization has a greater likelihood of developing more innovative solutions. An organization that does not reflect these population trends or does not take them seriously is not likely to succeed for long. It also magnifies the complexities of working in a team environment. OD practitioners who understand the complexities of global teaming (recall our discussions of team effectiveness in Chapter 11) are helping to design team interventions to maximize team effectiveness and helping teams become explicit about their roles and assumptions about how they work. OD consultants who work with clients and organizational teams can help managers \"recognize that all employees cannot be managed the same way. Individual employees, especially those from different generations or at different life stages, have different needs, goals, and motivators\" (Eversole, Venneberg, & Crowder, 2012, p. 618). Whether the challenges are between individuals of different age groups or cultural backgrounds, OD practitioners can work with teams and organizations to facilitate effective communication and enhance collaboration

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts