Question: Question: What action steps are taken to ensure that translingualism unit designs and assessments promote content to build on their bilingualism, promote stronger social-emotional identity,

Question: What action steps are taken to ensure that translingualism unit designs and assessments promote content to build on their bilingualism, promote stronger social-emotional identity, and work toward social justice Explain Why?

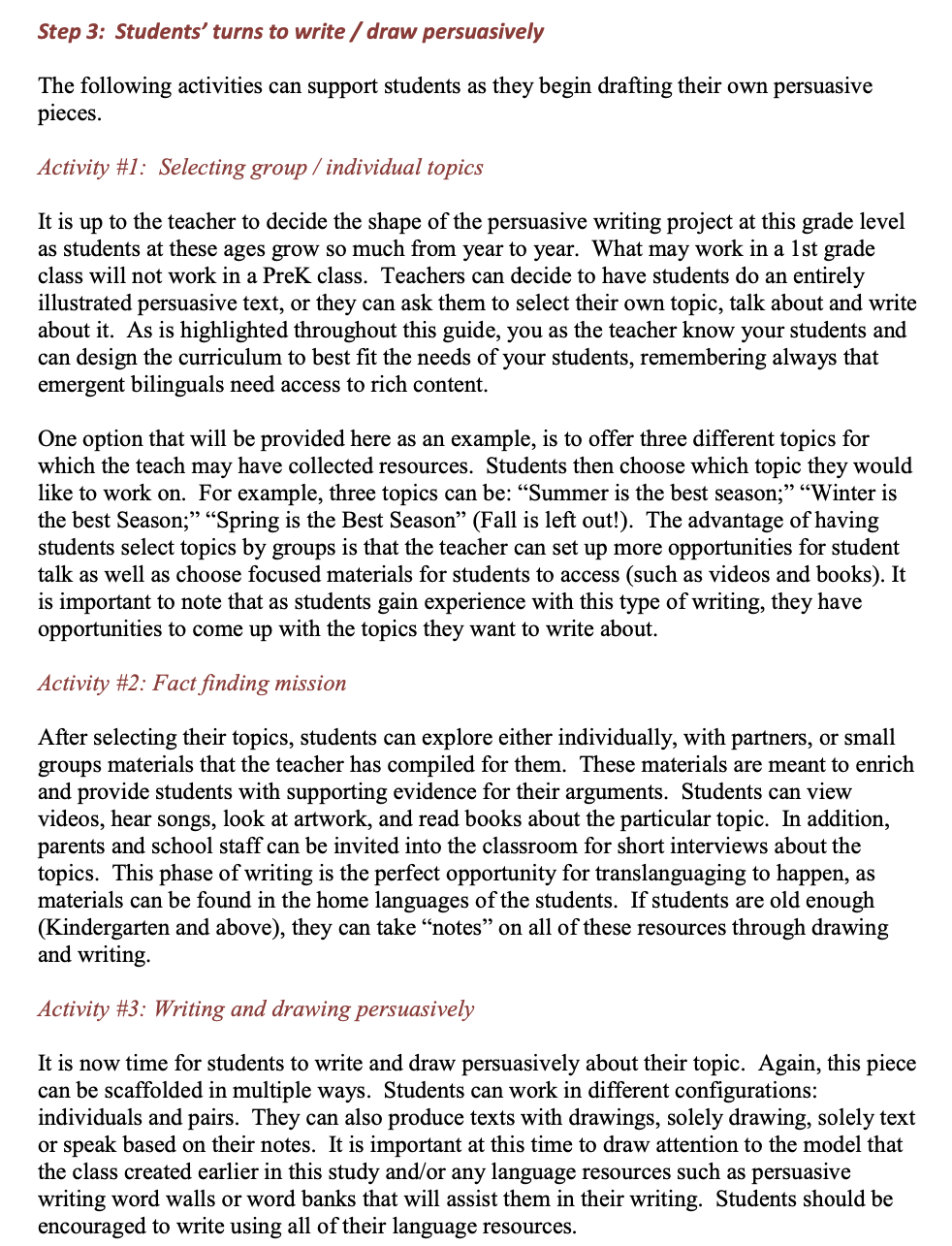

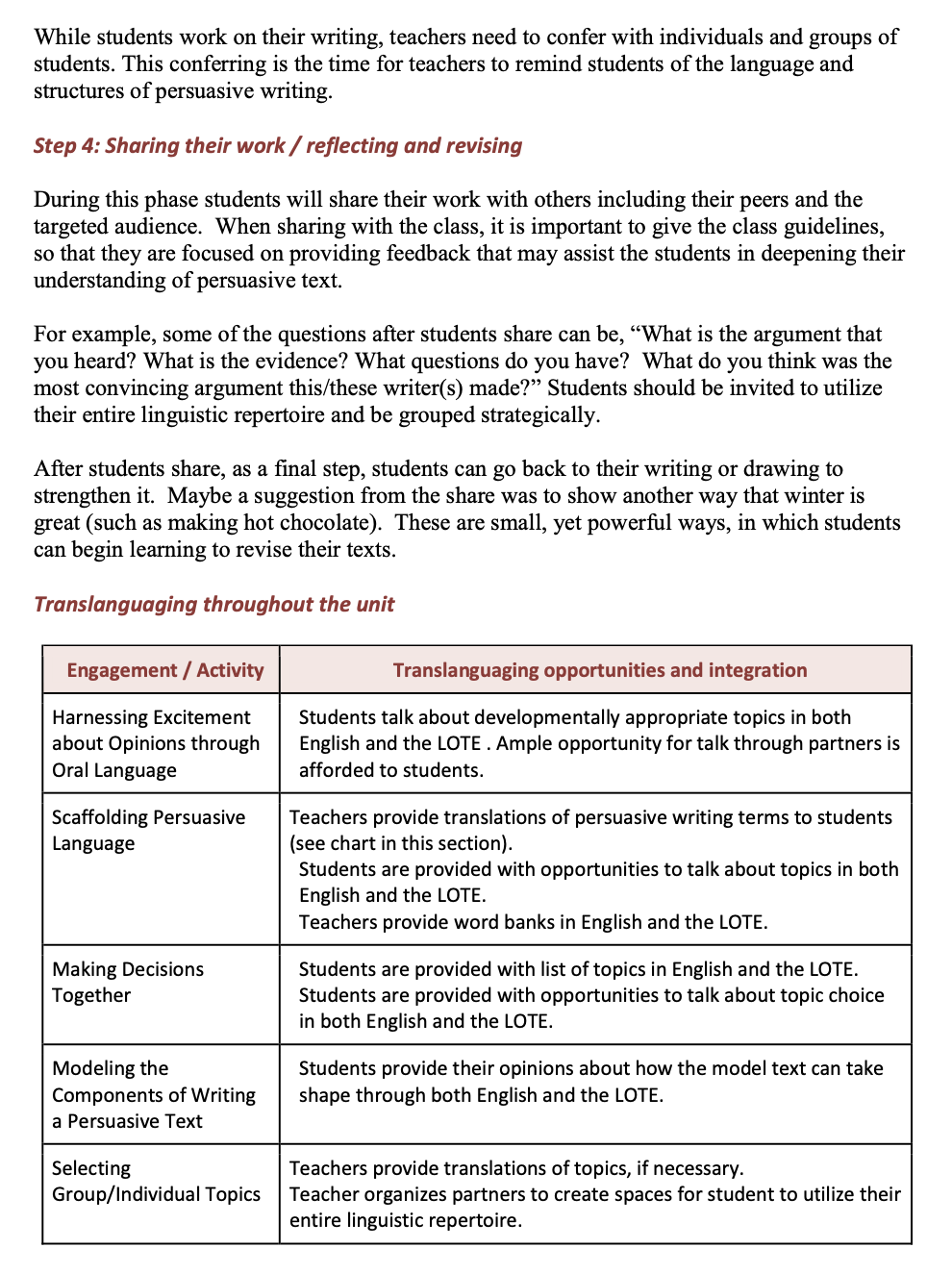

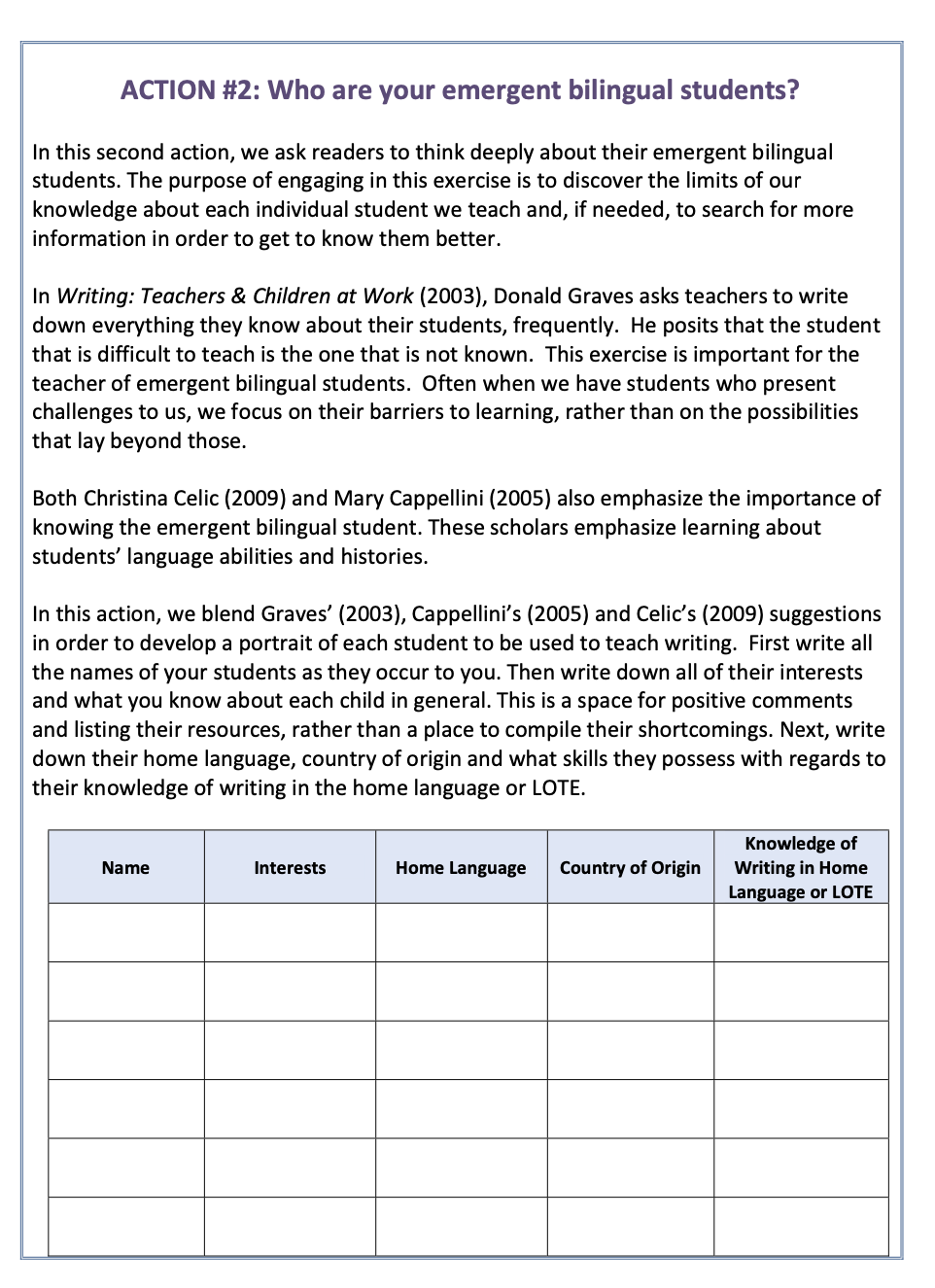

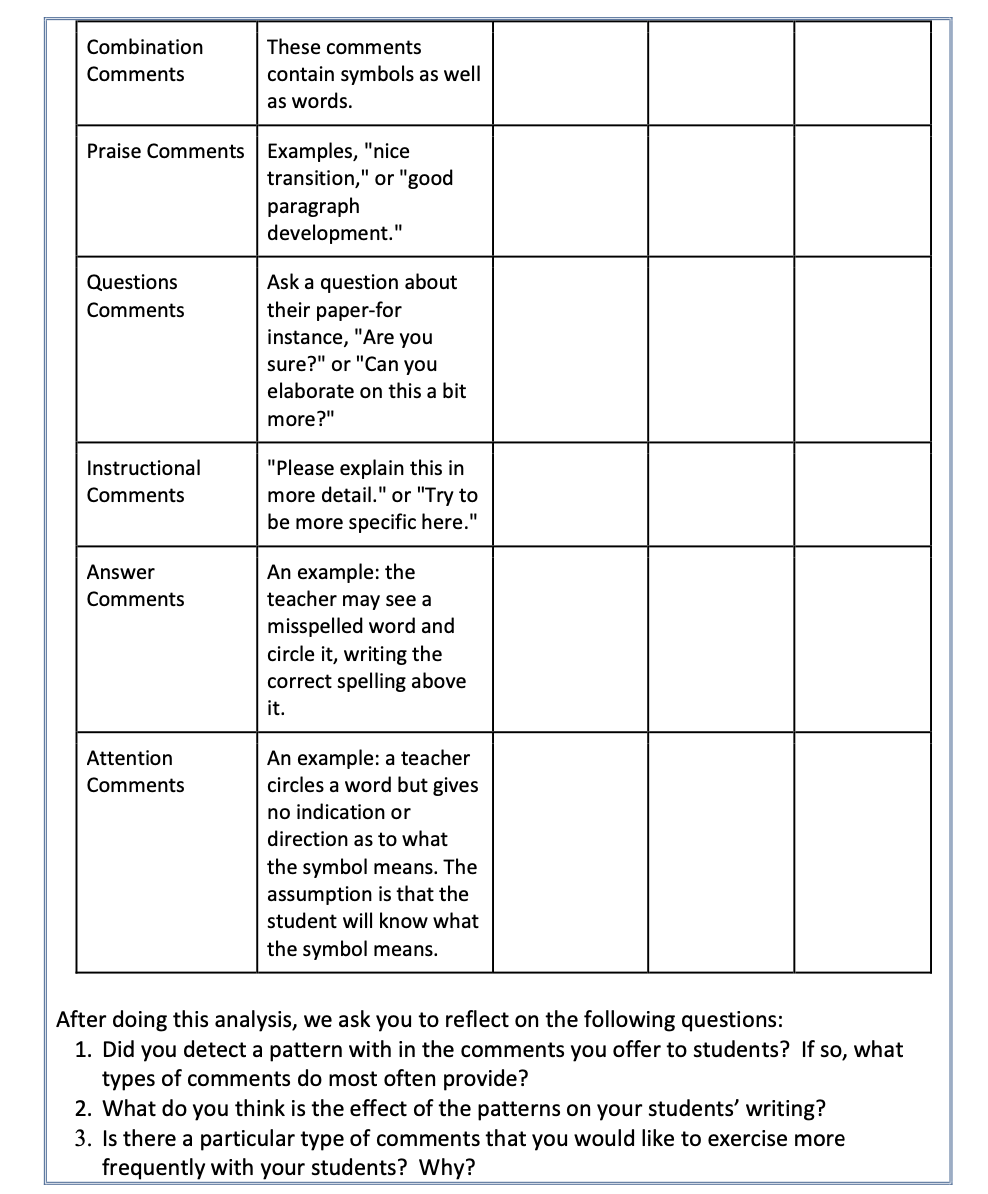

INTRODUCTION Emergent bilinguals are a diverse group of students who bring a range of resources and challenges to the classroom. In this guide, we extend an invitation to teachers of all grade levels, and across disciplines and programs, to examine how you currently instruct writing, and to try out innovative practices with your emergent bilinguals. We offer a novel language as a resource perspective on the teaching of writing, based on the principles of the City University of New York - New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals (CUNY-NYSIEB) project. Since Spring 2012, CUNY-NYSIEB has worked to support school communities around New York State as they improve education for this student population, guided by two non-negotiable principles: 1) Support of a multilingual ecology for the whole school; and 2) Bilingualism as a resource in education. The content in this guide merges CUNY-NYSIEB's approach with a long trajectory of scholarly work on writing instruction. This guide is not meant to be solely read, but also lived by teachers, as you make the ideas contained in this text your own, and truly adapt them to teach your own emergent bilingual students, whose needs may change throughout the academic year and from year to year. Our work catalyzes multiple dialogues. Firstly, we invite you to engage in conversation with your writing self" otherwise known as your identity as a writing teacher (Culham, 2015). Readers of this guide are encouraged to complete the actions which are sprinkled throughout the text. These short writing activities will jumpstart personal reflection about your classroom and provide you with opportunities to make connections with ideas in the text. Secondly, we would like teachers to discuss the approaches and activities in this guide with others, so ideas may be further developed with particular students and school contexts in mind. We are also in conversation with a rich tradition of thinkers and researchers in the field of writing. As such, we forward a conception of writing as a process (Fletcher, 2001; Graves, 2003; Heard, 2014; Murray, 2012). Process writing refers to all of the recursive actions which writers go through in order to produce a text -- this includes brainstorming, drafting, rereading of writing, sharing ideas with others, and revising. Language is inextricably intertwined with all of these components of the writing process. Therefore, translanguaging, or the fluid use of a person's whole linguistic repertoire across languages, is a natural fit with this conception of writing (Velasco & Garca, 2014). The writing process is also enriched when students use multiple modalities of language (reading, writing, listening and speaking) in order to access and express their ideas. Writing is not solely an intellectual task, but rather is developed socially, and through experience and engagement with art, technology, drama, play, music, and the world outside the classroom. Lastly, we believe that students must take an active role in the writing process. This means that their interests must be activated and employed when writing, and that teachers help students make connections to content and material. Writing tasks must also be authentic and have meaning for students, rather than solely being exercises for grading. The menu of strategies and tools in this guide are both student-centered and suggest authentic writing experiences for teachers to infuse into your writing curriculum. We hope that teachers who read this guide find a space to try out the writing tools we describe here with your students, regardless of the type of program students are in (Dual Language Bilingual Education [DLBE], English as a New Language [ENL], English Language Arts [ELA], or Native Language Arts [NLA]). Translanguaging is a powerful tool for all emergent bilingual writers to draw upon as they write in English,and in languages other than English (LOTE). Translanguaging can support, expand, and enhance student writing in general. As Hopewell (2011) writes, the outdated argument that a first language is a bridge to English must be abandoned to make room for a broader conceptualization of all languages contributing to a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts (p. 616). Translanguaging can assist students along all stages of the writing process and with a variety of purposes. It is often thought of as a powerful scaffold for students when they struggle to write text in one language. However, this is only one purpose of a translanguaging vision for writing, albeit one that is especially beneficial to students who are acquiring a new language. Writers also translanguage to express themselves creatively, to think about a subject, to connect to a given audience, and to promote their own self-development as writers. In this way translanguaging is an essential process during the writing process not only as a scaffold for those at the initial stages of learning a language, but throughout the emergent bilingual students' writing life. On a final note, this guide is premised upon the idea that you as the teacher are in the "driver's seat of your writing instruction. Regardless of mandated writing curriculum or demands that are placed on classroom instruction at any given school, teachers should adapt mandated curriculum and find spaces for authentic writing within it. Rather than viewing teachers as implementers of curriculum, we see teachers as creators. This quality of teachers is essential, as strong writing instruction practices flows from classrooms where students are known. This means that teachers are knowledgeable and curious about the home language resources that emergent ingual students bring to the classroom and harness these to advance student engagement and achievement in writing. In this guide readers will find five basic sections: 1. Personal Reflections on Writing 2. Theoretical Framework: A Translanguaging Pedagogy for Writing 3. Actions for Readers of this Guide 4. Tools to Leverage Translanguaging in Writing 5. Sample Persuasive Writing Units We invite you into our conversation about authentic writing instruction for emergent bilingual students, and hope you find our approaches and tools inspiring. PERSONAL REFLECTIONS ON WRITING We begin with our stories of how we learned to write in school. We provide these for you because we believe that in order to change writing instruction, we need to be aware of our history as learners. Following the stories, is Action #1, where we invite you to reflect on your own story as a writer, as we do here. Cecilia's story I grew up in Ecuador, South America. I went to the same school for 12 years between the 1970s and early 1980s. At this school, writing was used as a tool to support memorization and drills. Writing was never used as a tool for thinking, for self-expression, for reflection, for wondering, or for learning. The belief was that in order to learn to write, one first needed to do drills about each letter of the alphabet. Later on, once we had mastered the basics, we were expected to take dictation from the teachers or to copy information from the blackboard. This information would become the text we had to memorize for exams. Books were very expensive and scarce in Ecuador, so we rarely studied from them. We were also asked to do extensive exercises of verb conjugations in each tense and each pronoun, including the pronoun vosotros, which is not used in Ecuador. At school we never used writing as it exists in the world: to write letters, to post signs, to write a poem or a story, to learn about a particular topic. When we had to write compositions the focus was on orthography, penmanship and cleanliness, never on content or on editing, revising and crafting a piece. The teacher's focus was on the product, not the process of helping the writer grow in his/her writing abilities. We never made connections between writing and reading in order to study the craft of a writer, the structure of a text, or the specifics of a genre. Writing on my own was different. At home I kept a journal. This was the only space where I could reflect and react to what was happening in my life. I treasured both the journal and the time I had to write. English was the additional language we learned at school. English classes consisted mostly of translating vocabulary, diagramming sentences, studying verb tenses, conjugating verbs and practicing the dialogues from the book. We never used writing to study a social studies or science topic. There was a strong belief that before we could use writing to learn in English, we first had to master the English language. It was only in college that I discovered the power of writing as a tool for thinking, reflecting, expressing, creating, etc. In college, I encountered professors who provided me with the kind of feedback that led me to express my thinking in the clearest way possible. These professors also modeled what it was possible to do with writing. As I unearthed the power of writing, I learned to engage my bilingual K-2nd grade students at a school in Phoenix, AZ in writing projects that had deep meaning and relevance to their lives. Later on, as a Director of the Dual Language Bilingual Program at the same school, I continued to support teachers as we searched for ways to best support the students' growth as writers. Now as a college professor I strive to provide spaces for my students to further develop their identities as writers in a multilingual world. My work has impacted greatly by my experiences with the New York City Writing Project Summer Institutes as a participant and a co-leader, as well as the Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) Seminars offered by the Institute for Literacy Studies at Lehman College/CUNY. Laura's story I grew up in Queens, NY in the 70s and 80s. At that time, much like now, most public school students were children of immigrants, if not immigrants themselves, and working class. Writing was taught in a piecemeal fashion. My memory of writing in the early grades is of spelling exercises and responses to reading in a workbook. On rare occasions we were asked to answer prompts. One that I remember clearly is, what would you find at the end of a rainbow? These prompts were divorced from the richness of our daily lives. I do not remember ever writing about my family life or my friends -- it was clear that writing was about knowing how to spell words and put them together in simple sentences in response to a question. We never wrote in any genres -- such as poetry, descriptive reports, or procedures. Correspondingly, our exposure to books was limited. We were taught to read through a basal -- therefore, almost all of our reading was selected for us. The powerful connections between reading and writing were absent for us. As a parent reflecting on this now, it is clear that my parents, as many of the parents in community, did not have the knowledge, time, or cultural capital to demand a richer reading and writing curriculum. Despite how out-dated my experience seems, as an educator, I am struck by how it continues to occur to varying degrees throughout the United States. My secondary experiences reflected the same poor conception of writing instruction begun in elementary school. During my middle school experience, very little changed in terms of writing instruction, except that teachers told us that we could not write. In English class we mapped sentences, identifying nouns, verbs, etc. We were given spelling words, which we were asked to use in sentences. Once a week, the teacher would ask us to write a story using all of our weekly spelling words -- an innovation we all enjoyed. In High School, most of the writing I did was content based, conceived as response to reading. We were not taught to write, but were constantly evaluated through our writing. It was only during college when I realized that writing meant expressing a unique vision of a particular topic, and not demonstrating knowledge I had read. It was then that I began to learn to write. I continue to consciously work on writing daily. Sara's story I remember my first writer's journal. It was a marbled composition notebook which I had decorated with brightly colored pictures from magazines. As I lived daily life as a kid in my upper-middle class Brooklyn neighborhood in the 1990s, I followed the advice of my third grade teacher, and carried that notebook with me everywhere. After all, she said, real writers never know where seed' ideas for their next writing pieces might come from. I would free-write on park benches, on the stoop outside of our house, at the pizza shop. I could write from the perspective of the wall, or a flower, a snail, or a city bus. From my teachers, I also learned about the writing process. Books didn't just fall fully formed from the sky. You had to select your ideas, draft them, revise them with your friends and your teacher, and of course, have a celebration at the end of the month, where you'd be able to share your words with everyone. Moving from my progressive public elementary school to a progressive public junior high school, I experimented with many new kinds of writing: reviews, monologues and plays, poetry, fantasy stories, brochures, historical fiction, and personal reflections, each genre offering a different set of tools for expressing myself. When my foreign language teachers assigned writing pieces in Spanish, the work was challenging, but I had a great deal of experience writing in English, and trusted my voice, even if I knew the essay would be riddled with grammatical mistakes. As I grew older, writing assignments at school became more formulaic, more academic. I remember sitting in front of the computer with my mother for hours proofreading and reorganizing paragraphs. I sought out spaces for more creative writing, like the high school newspaper, and later, the college campus newspaper, the student blog, and university literary magazines. My peers on these publications -- exceptional young writers and editors -- - taught me to use journalistic lingo like ledes and nutgrafs when discussing the first paragraph of an article, and how to murder my darlings (to sacrifice my favorite turns of phrases), in the interest of a coherent story arc. Today, I recognize how privileged I was to learn to write in environments which valued my cultural capital, language, voice and self-expression, and made connections to the authentic ways that writing exists in the world. Now that I am a doctoral student, I write academic texts daily. Sometimes I feel like I am hitting the upper limit of my abilities as a writer. My main arguments get lost in a blizzard of extraneous words, and I succumb to the sickness that is passive voice. Even in those moments of frustration, more often than not, it's some strategy from the third grade -- free writing, writing from someone else's perspective, or asking a peer for help -- that saves the day. ACTION #1: What is your relationship to writing? In the first action, we ask you to reflect on how you learned to write in school, and how your history as a writer impacts your vision for writing instruction as a teacher. As noted in the introduction, we hope that all of these actions provide readers with an opportunity to personally engage with the ideas in this guide. Teachers' practices are shaped by their beliefs. When we reflect upon our personal histories with writing, the way that we were instructed to teach writing, as well as how we currently engage in writing practices, we are better able to understand how our mindsets impact our writing instruction. In the following action, we ask you to reflect on your writing history and then to consider based on your thoughts, how you want your writing instruction for emergent bilinguals to take shape. Please feel free to continue your reflection on another sheet of paper, if the space below does not suffice. o 1. Write about each of the following individual questions: What does writing mean to you? How did you learn to write? When did writing come easily for you? When was it challenging? What is your experience writing in a different language? O O 2. Based on this reflection, what kinds of writers do you want to see your students become? (including those that are emergent bilinguals) THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: A TRANSLANGUAGING PEDAGOGY FOR WRITING All teachers hold theories about what writing is and how to teach writing. Our beliefs about these fundamental aspects of teaching impact our instruction. It matters that we take the time to examine them. We know that readers may have some questions about the research which undergirds the ideas in this guide. This section offers a theoretical framework to answer those questions by bringing together research from the fields of writing instruction and the teaching and learning of emergent bilingual students. This framework is presented in a question and answer format so that readers can explore aspects of the rich background of writing research according to their choices. Within this section, we include two actions designed to provoke reflection about your theories and beliefs about writing instruction. Action #2 centers your practice on recognizing the emergent bilingual writers in your class, and Action #2 follows up with questions to help you examine your present and desired writing environment. What is writing? / What is not writing? Samway (2006) argues that writing, good writing, is a clear and evocative piece that captures the intellect and/or emotions of the reader (p. 22). Given this holistic definition of writing, Samway (2006) asserts that writing is not filling in the blanks, copying sentences or words, or making sentences from a word list (as an end to the engagement). Central to writing is the development of voice, and writing with power (Elbow, 1998). Writing is much more than what we read on the page or text. A good deal goes on behind the scenes. The writing process is inextricably tied to other language modalities reading, speaking, viewing, listening, performing, etc. (Lankshear & Knobel, 2011; Medina & Campano, 2006; Whitmore, 2015). As such, it is crucial that students are exposed to a range of high quality reading materials, as well as opportunities to speak (dialogue), create, reflect, critique constructively and listen to peers (Fletcher, 2001; Heard, 2014; Horn, 2005). The pivotal work done in these other modalities nurture writers; it provides them with schema about the structure and possibilities of writing, as well as supports students' idea development and the creative construction of meaning. For the emergent bilingual student, meaning-making is only possible if they can participate by utilizing their entire linguistic repertoire, what is called translanguaging (Garca & Li Wei, 2014). To truly encourage authentic writing and learning, teachers can create spaces for translanguaging in their classrooms (Garca, 2012). What do we mean by translanguaging and writing? Translanguaging refers to the language practices of bilingual people (Garca, 2012, p. 1). Bilinguals may be taught to operate in monolingual contexts, but emergent bilingual students often translanguage -- utilize their linguistic repertoires flexibly, without suppressing features from a particular language -- in order to make sense of their lived experiences in their homes and communities (Dwarte, 2014). At school, educators can leverage emergent bilingual students' translanguaging practices, creating spaces for them to use the linguistic resources they already possess to access rigorous content, and thus to be able to participate fully in all learning events (Garca, 2012). Good writing can be translanguaged -- featuring words from multiple languages, as in the work of Junot Diaz, who received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (2008) for his novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Writers can also translanguage -- speak, read, write, and think in multiple languages -- throughout the writing process, even if they are aiming to produce a monolingual text. Canagarajah (2011) has been a pioneer in thinking about how multilingual writers use their entire linguistic repertoire as one integrated whole. Rather than limit themselves to engaging in the writing process entirely in one language or another, which can stifle cognitive processing and expression, multilinguals may, for example, plan and take notes bilingually, even if their goal is to compose a formal essay in one language. They may speak about their ideas with peers in a particular language, but may compose bilingual texts inspired by those conversations. Through such acts, multilingual writers create a space to re-appropriate and resist traditional, monolingual academic discourses, and through it construct spaces for rhetorical efficacy. Canagarajah (2011) studied the narrative writing of one of his bilingual graduate students. He found that while the student was aware of audience and the expertise of her teacher, translanguaging (adding Arabic words, emoticons, italics and even Islamic art to her English text) allowed her to develop her voice, negotiate meaning, and engage with her intended audience in more complex ways. Utilizing her entire linguistic repertoire was transformational for this student, as it set in motion her creativity and criticality. Garca & Li Wei, (2014) and Canagarajah (2011) argue that educators need to study the practices multilingual students are constantly adopting. These researchers add that it matters that students' agency is encouraged as they make decisions about their use of translanguaging in their writing (Garca & Li Wei, 2014; Michael-Luna & Canagarajah, 2007). Canagarajah (2011 & 2013) coined two related terms to translanguaging, codemeshing and translingual. These terms refer to the process of fusing a variety of dialects and practices from languages and registers. We prefer the term translanguaging as used by Garca (2008) and Garca & Li Wei (2014). Translanguaging is multimodal, transdisciplinary, and it emerges from the contextual affordances in the complex interactions of multilinguals (Garca & Li Wei, 2014, p. 40). What is writing in the 21st Century? 9 The 21st Century calls for a new paradigm for the teaching of writing. We have named this paradigm the Translanguaging Pedagogy for Writing. From this perspective, variety, fluidity, and multilingualism are the norm (Garca & Li Wei, 2014). This pedagogy moves away from an ideology of monolingualism and monoculturalism as the standard (Dwarte, 2014). Bilingualism is no longer seen as a problem that needs to be eradicated. Instead, it is a resource that leads to deeper meaning in all areas of language: writing, listening, talking, reading, viewing, and acting on multimodal ways of conceptualizing writing. A 21st Century perspective on writing challenges the idea that there is a universal standard for writing which is static, discrete and separate (Menken, 2015). This point of view assumes that language is always changing, that we are all language learners, and are also creators of language (Horner, Lu, Jones, & Trimbur, 2011). Language, as Garca (2015) states, is about using/doing/performing "languages. Language is not something that exists in isolation, outside from our experiences and our being. It exists because we populate it with our own intentions (Bakhtin & Holquist, 1981). In the bilingual person, as Garca & Li Wei (2014) state, there aren't two separate languages, but one linguistic repertoire which bilinguals rely on to negotiate situations (Garca, 2015). Consequently, the bilingual child needs to come fully into the classroom with his/her entire linguistic repertoire. The 21st Century perspective on writing rather than being exclusive, is inclusive of multiplicity of voices and perspectives (Bakhtin & Holquist, 1981; Carini, 2010). While we dedicate only a brief section of this guide to writing in the digital era (see: Composing Multimodal Texts in the Writing Tools section), the 21st Century demands that teachers are aware, understand and support the many different ways in which students compose through digital media. As we continue the broad shift from reading words on a printed page to consuming media and text on screens (Kress, 2003), good writing is increasingly taking multimodal form, integrating sound, images, video, data visualizations, and computer programming languages. There are now many opportunities to network and to write for social participation (Blake, 2009). Writers today produce multimodal video documentaries, memes, websites, photo essays, podcasts, interactive maps, social media campaigns, video games and other digital texts. What is the CUNY-NYSIEB vision of writing? The CUNY-NYSIEB vision of writing embodies a strengths-based perspective (Carini, 2010), and therefore requires that we move away from deficit views and myths, such as: bilinguals can't write; they have too many writing problems, they don't like to write; they are reluctant writers; they need to be taught the skills of writing before being asked to write originally and independently; and they have to learn to write to pass a test. Instead, it invites emergent bilingual students to utilize their entire linguistic repertoire to construct meaning and fully participate in the life of the classroom, taking a stance of strength. It is a necessity and a reality for bilinguals to draw on their entire linguistic repertoire on a daily basis. For this, translanguaging lives in the language practices of the writer (Garca & Li Wei, 2014). CUNY NYSIEB's vision for writing in the 21st century builds on, supports and honors the students' linguistic repertoires. It asks what writers are doing with language, what their intentions and purposes are, and how writing exists in the world. It invites the writer to consider the instance, the reasons, and the purpose of their writing. Therefore, it matters that students have opportunities to write in authentic contexts. Authenticity of writing purpose leads to more opportunities for students to engage their entire linguistic repertoire. A translanguaging pedagogy for writing builds on the two CUNY NYSIEB non-negotiable principles (http://www.nysieb.ws.gc.cuny.edu/our-vision/): Support of a multilingual ecology for the whole school Bilingualism as a resource in education. The CUNY NYSIEB vision for writing invites teachers to reflect deeply about their pedagogical language knowledge (Faltis, 2013) in order to become well informed about how to best capitalize on the language practices students' bring with them and must rely on, if they are to fully construct meaning. It challenges teachers to grapple with new ideas about language and the possibilities the pedagogy of translanguaging offers (Garca & Li Wei, 2014). How do emergent bilinguals experience writing? At its core, writing is the creation of meaning (Berthoff, 1981; Hudelson, 1989, 2000, 2005). Writers learn how writing works and what it is for within their cultural contexts at home, at school and in the classroom, and in their communities and the larger world. While at home, emergent bilingual children may learn that writing has a purpose and an audience and that their bilingualism is part of their lived experience (Dwarte, 2014); at school they often learn that their only audience is the teacher, who, for the most part, expects them to write in English solely. Students view the teacher's job as primarily to correct and grade their work, but rarely to respond to it in a dialogical manner. School offers limited opportunities for emergent bilingual students to seek the support and guidance of an authentic audience (teachers, peers, and others outside of the classroom) as they attempt to clearly convey their ideas. They seldom learn that writing can be a process of discovering what one means (Hudelson, 2000). Researcher Anne Haas Dyson (2015) states that under these circumstances, instead of learning to write, children learn to negotiate how to do school because sadly, writing at school is often only about writing the correct answers. Teachers' beliefs about the teaching of writing have profound implications for how children understand writing (Hudelson, 2005). To truly know how the emergent bilinguals in their classes experience writing, teachers should ask themselves: What are the purposes for writing I offer in my class? Do my students have opportunities to write for authentic audiences? In what ways do I support the development of the emergent bilingual writer's ideas? In what ways do I invite emergent bilingual students to bring their entire linguistic repertoire, so that they can fully construct meaning as writers and thinkers? In what ways can translanguaging in writing offer emergent bilingual students at all levels opportunities to express themselves and what they know? . . When educators view emergent bilingual students' homes, families, communities from a perspective of strength (as having a wealth of socio-cultural writing resources), emergent bilingual children will experience a richer learning writing environment (D'warte, 2014). It matters that the teacher learns what are the contexts, including funds of knowledge for writing in the homes and communities where the children come from (Mercado, 2005; Moll, Amanti, Neff & Gonzlez, 1992). Children need opportunities in the classroom to write for particular purposes and audiences by being able to capitalize on their entire linguistic repertoire (Dwarte, 2014, Velasco & Garca, 2014). It is only then that they will be able to write for self-expression, to document and present their learning in a content area, to compose in different genres, to respond and examine literature, and to advocate for issues that matter to them in order to create a more just world. While it is evident that emergent bilingual children also need explicit instruction and scaffolding, they also need to learn that conversations, collaborating, receiving feedback, discussing with others their work, examining the work of published authors are important recursive components of the writing process. Emergent bilingual children need to know that their voices matters and that they can be developed further -- that writing can help them make sense of their worlds, as they use writing to learn and wonder about it. Clearly, the only way to accomplish this is when they are invited to bring in their entire linguistic repertoire as the construct meaning, express their understandings, and have opportunities to consider new ways of using language (Horner et. al, 2011). ACTION #2: Who are your emergent bilingual students? In this second action, we ask readers to think deeply about their emergent bilingual students. The purpose of engaging in this exercise is to discover the limits of our knowledge about each individual student we teach and, if needed, to search for more information in order to get to know them better. In Writing: Teachers & Children at Work (2003), Donald Graves asks teachers to write down everything they know about their students, frequently. He posits that the student that is difficult to teach is the one that is not known. This exercise is important for the teacher of emergent bilingual students. Often when we have students who present challenges to us, we focus on their barriers to learning, rather than on the possibilities that lay beyond those. Both Christina Celic (2009) and Mary Cappellini (2005) also emphasize the importance of knowing the emergent bilingual student. These scholars emphasize learning about students' language abilities and histories. In this action, we blend Graves' (2003), Cappellini's (2005) and Celic's (2009) suggestions in order to develop a portrait of each student to be used to teach writing. First write all the names of your students as they occur to you. Then write down all of their interests and what you know about each child in general. This is a space for positive comments and listing their resources, rather than a place to compile their shortcomings. Next, write down their home language, country of origin and what skills they possess with regards to their knowledge of writing in the home language or LOTE. Name Interests Home Language Country of Origin Knowledge of Writing in Home Language or LOTE What is the role of oral language? What is the role of multimodalities? Writing for our youngest students begins through talk (Gort, 2012). Students play with language and ideas in order to generate topics and situations in which to write and draw about. This often occurs in the company of other children. For emergent bilingual students, playing with language as a stage in pre-writing occurs fluidly between both languages (Gort, 2012). Therefore, writing instruction for young emergent bilinguals must be supported with ample opportunities both planned and unplanned for multilingual talk. This can take shape through turn and talks, writing partners, and free talk while writing. It is important to emphasize that oral language flows from experience. Multimodal theory enriches our understanding of how multiple realms of experience linguistic, visual, auditory, gestural, and spatial -- can enrich language learning and literacy development (Martens, Martens, Hassay-Doyle, Loomis & Aghalarov, 2012). When students focus on the both the text and the illustrations of picture books or explore books through art and drama, they not only develop strong comprehension but are also able to create and write based on those texts (Martens et al. 2012). Such exploration also helps young students learn about characters, story elements, and text features. For example, in one bilingual kindergarten classroom, before having students work on writing stories for the first time, the teacher engaged students in creating puppets of their characters. These characters then became objects used in dramatic play with language and story. After students had ample time to make up stories and scenes with their puppets, they engaged in writing. It is important to note that all of these experiences can occur in both the home and the new language. Oral language has a key role to play in older emergent bilingual students' writing. In reference to children in grades 2-6, Swinney & Velasco (2011) note that oral language allows students to talk about what they are learning as well as expand their language. They state that teachers have a crucial role in modeling conversation and dialogue. In her study of adolescent emergent bilingual writers, Kibler (2010) found that students spoke about their ideas for writing assignments, and assessed their writing using their entire language repertoire. Their authorship emerged out of these conversations about writing, underscoring how essential oral home language use was to the writing process. Siegel (2012) emphasizes that multimodal practices have promise also for older learners. She notes that students bring their multimodal practices to school regardless if they are the focus of instruction. In addition, when a multimodal approach is taken, students who are often viewed as at risk are suddenly acknowledged for the resources they bring. As Siegel writes, multimodality is in the air in those classrooms where teachers and students read manga, design digital stories, produce podcasts, and perform dramatic tableaux (2012, p. 678). As her list suggests, adopting a multimodal approach can help ensure writing work is authentic, student centered, and focused on audience. What do teachers of emergent bilinguals need to know about writing in the early years? For teachers working with young emergent bilingual children, families and communities are an invaluable resource, since the parents are the children's first educators. Teachers should study, from a perspective of strength, the particular cultural and linguistic traditions in the child's home and community, and draw on them (Alvarez, 2014; Arpacik, 2015; Genishi & Dyson, 2009). Teachers can learn about the family's and child's literacy experiences by sending home a survey, inviting parents into the classroom, and having informal conversations. This data can inform the teacher about the emergent bilingual child's interests, talents, resources, experiences, needs, etc. (Meier, 2004). Meier (2004) states that, we write in order to express ourselves, make connections with others, and better understand the worlds we live in both real and imagined (p. 102). In the preschool classroom, emergent bilingual children need to have ample opportunities to explore writing for authentic purposes (Whitmore, Martens, Goodman & Owocki, 2005). Play is young children's work. Therefore, writing needs to be weaved into play on a daily basis. While a classroom's writing center is important (and needs to be stocked with interesting writing materials), the classroom should be filled with additional writing possibilities, such as a station for sign-making in the block area, and paper pads in the dramatic play area so that children can use them in the context of scenes at the doctor's office, pizzeria, bakery, post office, etc. Learning to write one's name can happen as part of the daily routine of taking attendance, signing up for an area to play in, or signing their name in a thank you letter to a visitor. These writing opportunities should mirror the languages of the community where the children come from, as well as English. Sadly, in many kindergarten classrooms, the idea of play as child's work is rapidly disappearing. We feel strongly that at this age level children need to continue to have meaningful, authentic, developmentally and linguistically appropriate writing experiences. The role of the teacher is to model, support and scaffold children's attempts to figure out what writing is for and how it is done, while inviting children to genuinely utilize their entire linguistic repertoire. It is critical that teachers legitimize the children's home languages and challenge a monolingual and monocultural standard, thus, inviting students to perform identities that reflect their entire linguistic repertoire (Gort & Sembiante, 2015). Emergent bilingual children need ample opportunities to draw, use art, perform, write [use invented spelling], and dictate their ideas. These are the tools (in addition to social interaction) that allow children to figure out the alphabetic system as containing symbols that convey meanings. It is important to remember also that reading compliments writing, so emergent bilingual children need to hear read alouds on a daily basis. They also need opportunities to write books, even though they might not know fully the alphabet yet. The emergent bilingual child who is writing books is engaged in other important higher order thinking processes: composing, crafting, engaging in work over time, researching about the topic, studying other author's work, etc. (Wood Ray & Glover, 2008). The child should be invited to utilize their entire linguistic repertoire during these experiences. In addition, opportunities for performances in which children become the story not only offers children new ways of experiencing literacy, but it reminds educators that the body is central to early literacy development (Whitmore, 2015). . The early childhood teacher can ask her/himself: Are the writing engagements I create in the classroom embedded in the social and intellectual life of the classroom (Meier, 2004)? In what ways do I invite the students to utilize their entire linguistic repertoire to construct meaning and become an important member of the classroom community? . What do teachers of emergent bilinguals need to know about writing in elementary school? The emergent bilingual writer who develops as a confident writer, does so because he/she has had meaningful, authentic, varied and holistic experiences with writing (National Council of Teachers of English [NCTE], 2008). When emergent bilingual children have had these opportunities, they know what writing is for, why people write, and what people do with writing (Britton, 1987; Horner et. al, 2011; Hudelson, 2000, 2005; Vygotsky, 1978). These types of experiences need to start from the very beginning of the elementary years. Teachers don't need to wait for a child to learn the alphabet before engaging them in meaningful writing experiences. To begin to develop a strong identity as writers emergent bilinguals need to write daily (journals, free writes) even if only for a few minutes. One becomes a writer by writing, the same way one becomes a piano player by playing the piano (Wood Ray, 2001). The children should be invited to write these entries daily in the language of their choice and without worrying about errors. The purpose of these experiences is to build fluidity while learning to write extensively (NCTE, 2008). There will be other opportunities to focus on other aspects of the writing process such as: revising, grammar corrections, editing, etc. Emergent bilinguals in elementary school need to have opportunities to write for authentic audiences, even if this means the teacher has to carve out some time from the busy curriculum. A focus on the emergent bilingual child's intentions and meanings as a writer is critical. Students need to experience what it means to write and learn about a topic one cares deeply about or a topic one is curious about. There are ample opportunities for these kinds of writing experiences through the content areas, whether in English or in the LOTE (Owocki, 2013). They can work collaboratively in these writing experiences by pursuing answers to questions that matter to them. The questions can also arise from issues (content) the emergent bilingual children are studying. These experiences will help strengthen students understanding of audience and development of voice as writers (NCTE, 2008). a Emergent bilingual children also need ample opportunities to experience writing as process: one crafts, revises, and edits a draft before it becomes a final product. This is not a linear process but a recursive process (NCTE, 2008). Throughout the writing process children experience receiving feedback and constructive criticism from others. They also support other writers, read mentor texts from a writer's perspective, share their published work and celebrate the work of others. Emergent bilingual students should have writing experiences that involve all genres. The types of genres and quality of texts emergent bilingual children read will influence their writing. Velasco and Garca (2014) found that emergent bilingual students utilized translanguaging throughout all the steps of the writing process. They strongly recommend that teachers open up the spaces for emergent bilingual students to capitalize on their entire linguistic repertoire in order to fully participate in each aspect of the writing process. Education for democratic participation has to engage students in the development of their own agency (Garca & Li Wei, 2014). Teachers can reflect on questions such as: What are the opportunities for emergent bilingual students to engage with issues that involve social action? In what spaces might I provide more opportunities for authentic writing? . . Without a doubt, emergent bilingual students will become deeply engaged in writing when they can study and write about issues that matter to them, while developing expertise in a subject and composing their work for an authentic audience. In addition, they will learn the power of writing in a democracy and how to advocate for a more just world (Cioe-Pea and Snell, 2015). What do teachers of emergent bilinguals need to know about writing in middle schools? Middle school-aged students are actively discovering, exploring, and creating their identities. They test and resist boundaries, because, as Lucy Calkins (1994) writes in The Art of Teaching Writing, they have a need to understand [their] lives, to find a plot line in the complexity of events, to see coordinates of continuity amid the discontinuity (p. 158). Under the guidance of a savvy but flexible teacher, students can use writing to help them figure out who they are and want to be in their world. It matters that teachers learn to listen to the students' own voices (National Commission on Writing, 2009). At the same time, middle school students are expected to use writing to demonstrate their knowledge of academic content, and their writing must meet increasingly higher expectations for critical thinking, argumentation, organization, and voice. Even given the constraints of middle school expectations and schedules, Calkins (1994) cautions against giving students "writing process exercises and advocates a model wherein students develop their own writing projects at their own pace, drawing on their hobbies, interests, and the poignant, turbulent details of their lives (p. 174). Teachers should harness the power of the peer group, spending time helping students build community and trust before they review each other's writing. Middle school teacher Gretchen Hovan (2012) affirms, Writing group transformed how my students wrote. They became more comfortable with revising, in part because going through the revision process with three other people hearing their ideas, offering feedback and hearing others, seeing group members' revision processgave them more ideas about how to approach their own writing and revision. (p. 53) Nancie Atwell (2014) writes about the multiple roles a teacher plays in a writer's workshop at the middle school level, including a listener and a teller, an observer and an actor, a collaborator and a critic and a cheerleader (p. 21). She stresses that while ideally the writer's workshop is a space for students to make their own decisions as writers, teachers should not shy away from drawing on their knowledge to push students to solve problems and try new things, as students become more independent writers. Emergent bilingual writers at this age may experiment with their linguistic identities, developing positive, negative, or more complex attitudes about their home and new languages. At this age, youth are perceptive of social prejudices, and their attitudes about language are often influenced by the status of the languages in their communities (Menyuk & Brisk, 2005). They need plenty of opportunities to hear, read, and speak their languages in context, and to write in their languages (if they have been or are being taught to write in their home language). Such practice and exposure will not only help them build positive, prideful associations with their home language and cultures, but will help them negotiate content and make meaning as they write in English and/or in a LOTE. In a study done by Garca and Kano (2014) emergent bilinguals with a range of diverse language abilities used translanguaging to scaffold, enhance, and expand their learning. Translanguaging served different purposes for each student, yet it consistently allowed them to access deeper and more complex content. Emergent bilingual students' comfort levels and experiences with writing vary with their academic backgrounds, their family members' education levels, their home and new language proficiencies, and their own motivation, among other variables (Menyuk & Brisk, 2005). Writing may have also been taught differently in their countries of origins, and they may be unfamiliar with a writing workshop model. A middle school teacher can ask him/herself: What are the spaces I create for my emergent bilingual students to engage fully as I writers? In what ways do I nudge them to solve problems, support one another and try new things as writers? In what ways does translanguaging assist students to express themselves and to find their voices in both English and the LOTE? . . What do teachers of emergent bilinguals need to know about writing in high schools? There are many factors which contribute to the kinds of relationships that older adolescent emergent bilinguals develop with writing; including their age at arrival to the United States, whether they attended school in their country of origin, the quality of the schools they attended in their home countries and/or in the United States, experiences writing in their home languages and English, and their parents' and families' education levels. Variations in these characteristics make teaching writing to emergent bilinguals at the high school level especially complex (Faltis & Coulter, 2007). Also complicating the work are the high standards for students' academic writing at the high school level (Fu, 2009). Students must use technical and discipline-specific vocabulary, and their writing must demonstrate knowledge of concepts from math, the sciences, history, and other subjects. At the same time, according to Schleppegrell, every school task writing definitions, reporting on an experiment, describing an event has an expected textual organization. Each genre, or text type, has, with great variation, associated register (grammar and discourse) features that construct it as a genre of a particular type (2006, p. 56). Fu (2009), reflecting on prior research she had conducted (Fu & Townsend, 1998), concludes that emergent bilingual students who are better writers in their native language learn to write in English with less frustration than students who are poorer writers in their native language (p. 25). Fu (2009) encourages students who are beginning to write in English to draft in their home languages so as not to stifle thinking capacity and expression. As their English proficiency comes to match what she calls students' "thinking level, they might begin to draft in English, so that more idiomatic English texts can result. Emergent bilinguals who learned to write academically in a different cultural context may also have to negotiate new and different expectations for academic writing in the United States. As Menyuk and Brisk (2005) write, "different cultures have different rules based on their own philosophical ideas of the purpose of a academic writing, and the responsibility bestowed upon writer and a reader (p. 170). High school classrooms are also populated by students who have less experience reading and writing in their home languages. In New York State, the term Long Term English Learners (LTELs) is used to denote emergent bilingual students who were primarily schooled in the United States, but due to poor quality schooling and other circumstances, still struggle with English and/or other academic subjects. Ascenzi-Moreno, Kleyn & Menken, et. al. (2013) critique the term LTEL for its tendency to pathologize the students' complex languaging practices and the length of time it takes an individual student to acquire the academic language and literacy skills that secondary schools demand (p. 1). They stress the importance of learning about these students' schooling history and building on students' oral home language practices. Students who are new to the country, and have low home language literacy and/or attended school infrequently in their home countries are termed Students with Interrupted Formal Education (SIFE). There is a great deal of diversity within this subgroup: students have their own unique strengths and face different challenges (Garca, Herrera, Hesson, Kleyn, et. al., 2013). According to the practitioner-research teams comprising the Bridges to Academic Success program housed at the CUNY-Graduate Center, teachers of SIFE students are advised to "highlight the patterns and big ideas repeated across disciplines so students might explicitly develop academic language, literacy, and habits of mind. In writing, SIFE students should use home language as a resource and should focus on meaning and sense- making well before syntactical accuracy (Bridges, 2015). High school teachers of emergent bilingual students can ask themselves: What are the spaces in my classroom for emergent bilingual students to engage fully as writers in the different content areas? . . . How do I provide relevant and rich educational experiences to all students? In what ways do I take into account their prior schooling experiences, home language and literacy practices? What is the role of the writing environment? Sharing one's writing, receiving public feedback, and critiquing the work of others involves taking risks, especially when one is learning to write in a new language. A strong community can support emergent bilingual students in moments of vulnerability, such as when they make their work visible not only to their teachers, but also to classmates. The goal is to create a community where being a writer who draws from his/her entire linguistic repertoire is valued. How the teacher establishes the classroom community of writers matters (Britton, 1987). It takes time to establish trust. Norms for responding to one another's work need to be discussed by all members of the classroom community. In these conversations, students should reflect on what helps create an environment where one feels known, and can safely receive support from others, as well as provide feedback. The classroom needs to be student- centered, which means that even the physical arrangement of the students' seats need to allow for dialogue with one another. In this setting the teacher is not the sole provider of knowledge (Britton, 1987). At the same time, the teacher needs to make her/his own writing process visible to students and provide opportunities for the students to notice authentic struggles with her/his own writing process. It matters when the teacher sees him/herself also as a writer in the classroom. Katie Wood Ray (2001) argues that we would not take piano lessons from a teacher who does not play the piano. Wood Ray contends that the same stance needs to apply to the teaching of writing. As we stated before, if a teacher is going to teach writing, he/she must also practice being a writer. Students need daily writing routines, ample time to write, opportunities to talk as well as quiet time, high and clear expectations, as well as choice (Wood Ray, 2001). While the tone of the writing time is essential, how the teacher organizes the physical classroom environment in order to welcome and fully support the student's entire linguistic repertoire is also of critical importance (Celic, 2009). In Action #3, you will find some questions that we pose with the intention of helping teachers think about the language ecology of your classroom and how it supports emergent bilingual students utilize their entire linguistic repertoire as writers. In addition, it is important to consider also the ways in which you can utilize language as a resource in your pedagogy, as you teach writing to emergent bilinguals. You will find some questions in Action #3 to guide you in this reflection. ACTION #3: Describe your writing environment In this third action, we ask you to think about the writing environment that currently exists in your classroom as well as your vision for your classroom's writing environment. The questions below draw from the two CUNY NYSIEB non-negotiable principles. Reflecting on these questions will help you consider ways to create an environment that welcomes and supports translanguaging and builds a community of writers. The goal of this action is to identify areas with respect to the environment in which to strengthen and develop. With regards to principle #1: 'Support of a multilingual ecology for the whole school, think about the following questions: What opportunities do students and families have to use home language during writing activities that take place in your classroom? How are other languages visible, palpable in the writing landscape of the classroom? What does the language landscape of your classroom look like? Does it represent the language practices of the students in your classroom? How do different texts support, enhance, nurture and challenge the imagination of the writer's language practices and cultural experiences at the school? How do the texts support multiplicity of voices and deeper thinking? With regards to principle # 2: Bilingualism as a resource in education, think about the following questions: Who are my students? What are their languaging practices? What strengths do they bring? How do I capitalize and build on these? (See Action #2 for more). In what ways are the writing-language practices of ALL my students not only recognized but also leveraged as a crucial instructional tool? Dol explicitly state in my classroom that students can/should utilize their entire linguistic repertoire in order to fully participate in the writing engagements? How dol address these varied language practices in my teaching of writing? What resources do I provide? How do I structure the class so that they can engage their entire linguistic repertoire? What adaptations do I need to provide to the writing tools we use? In what ways do the resources I provide support, nurture and challenge the students' entire ling