Question: Question: What is culture? 9 Culture and Cultural Diversity and Their Relationship to Academic Achievement Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able

Question: What is culture?

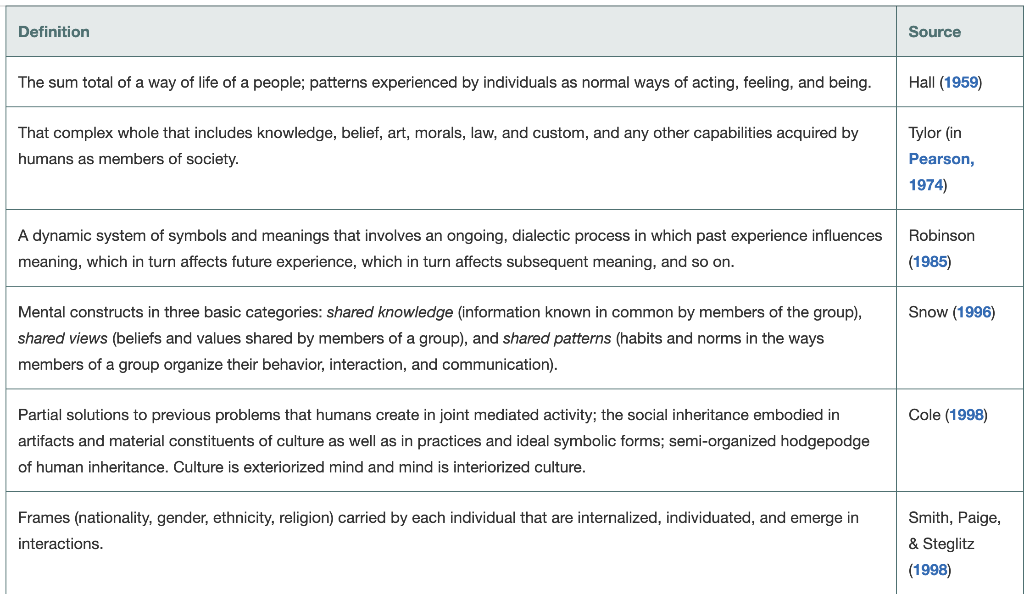

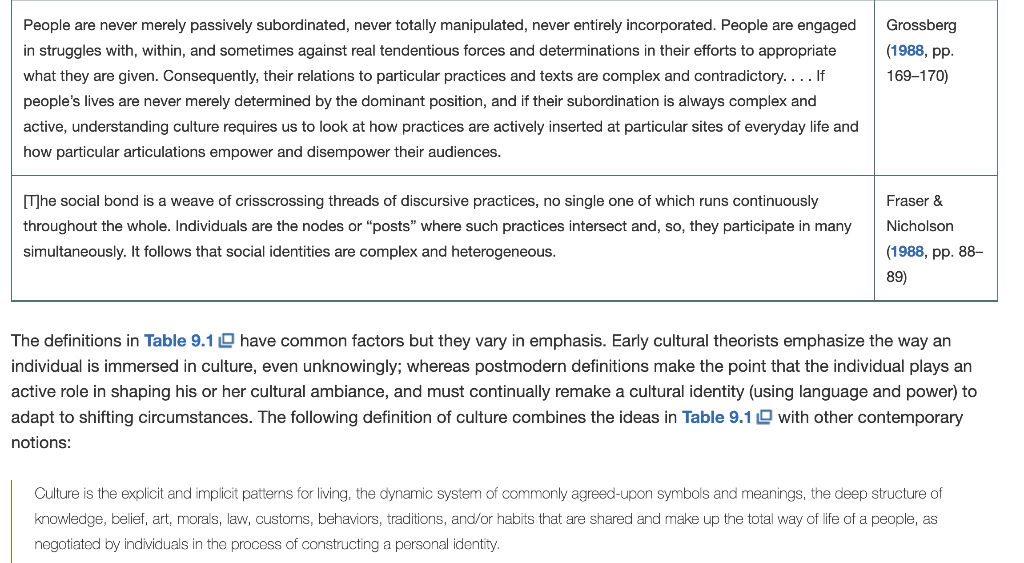

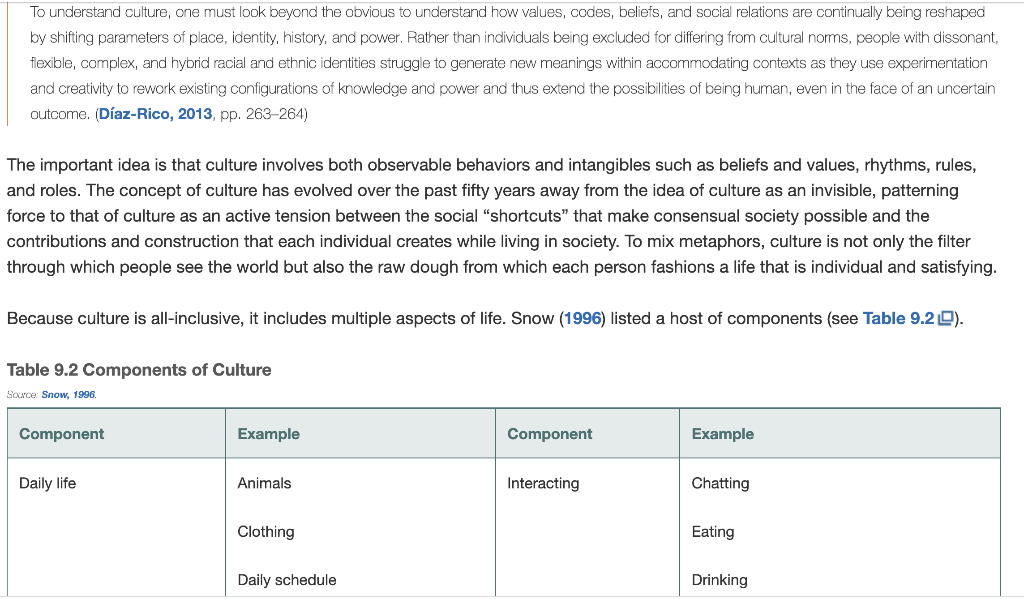

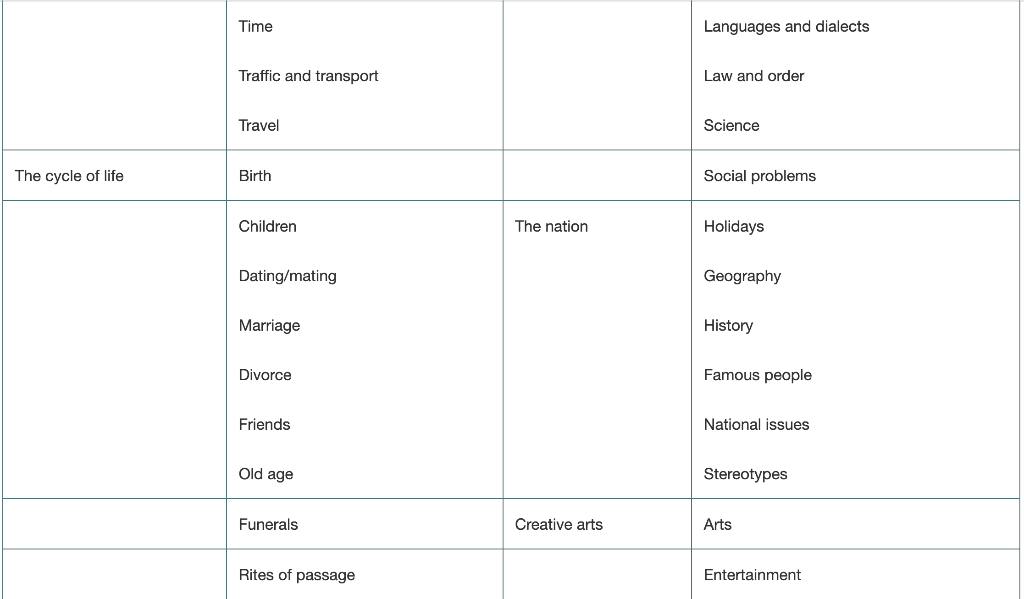

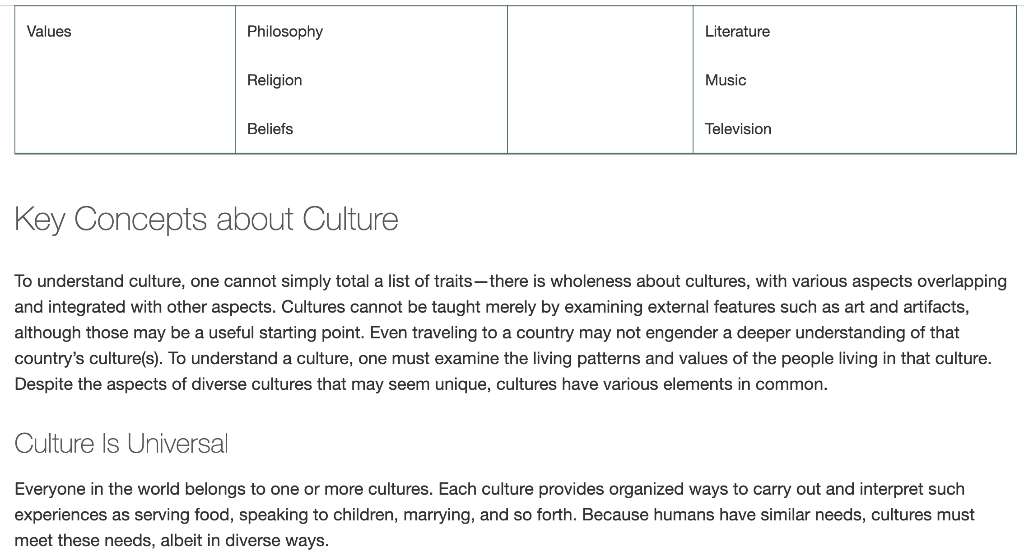

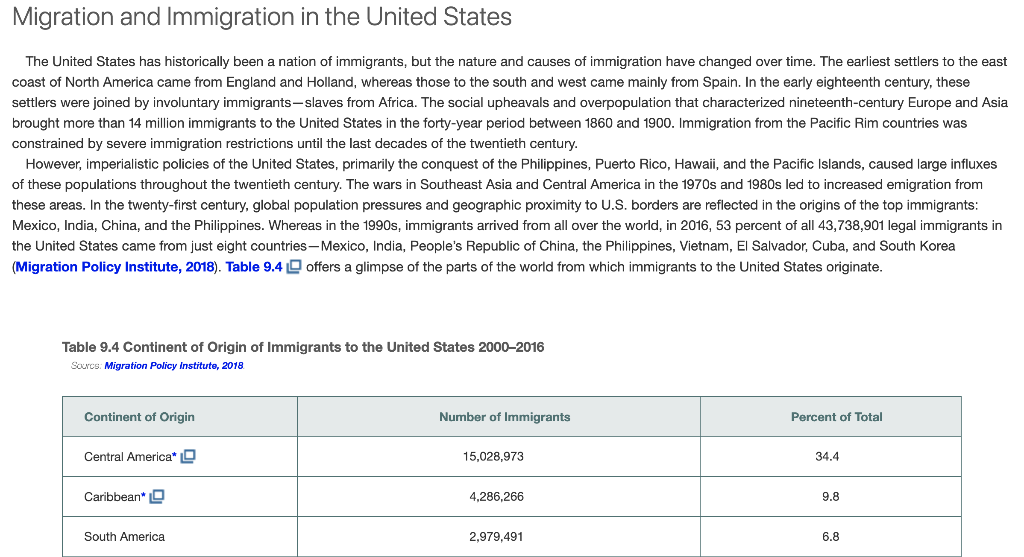

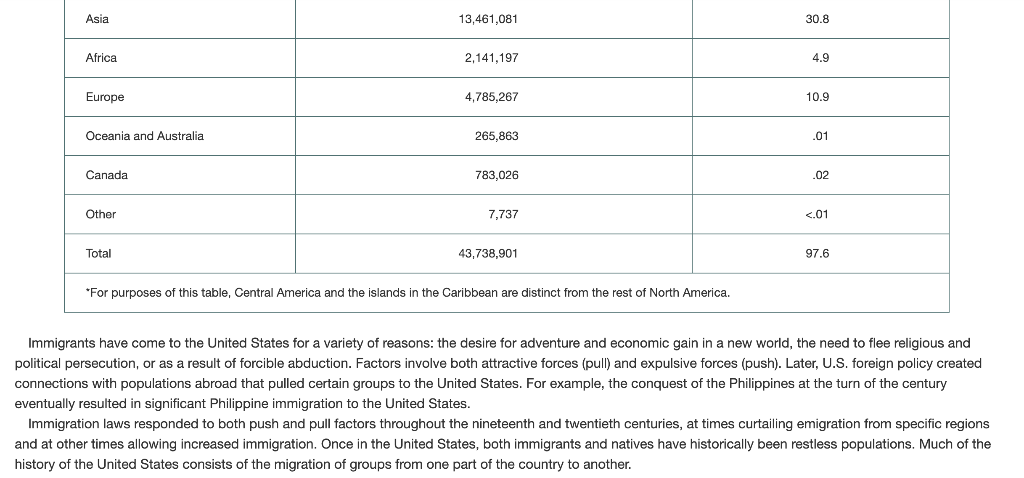

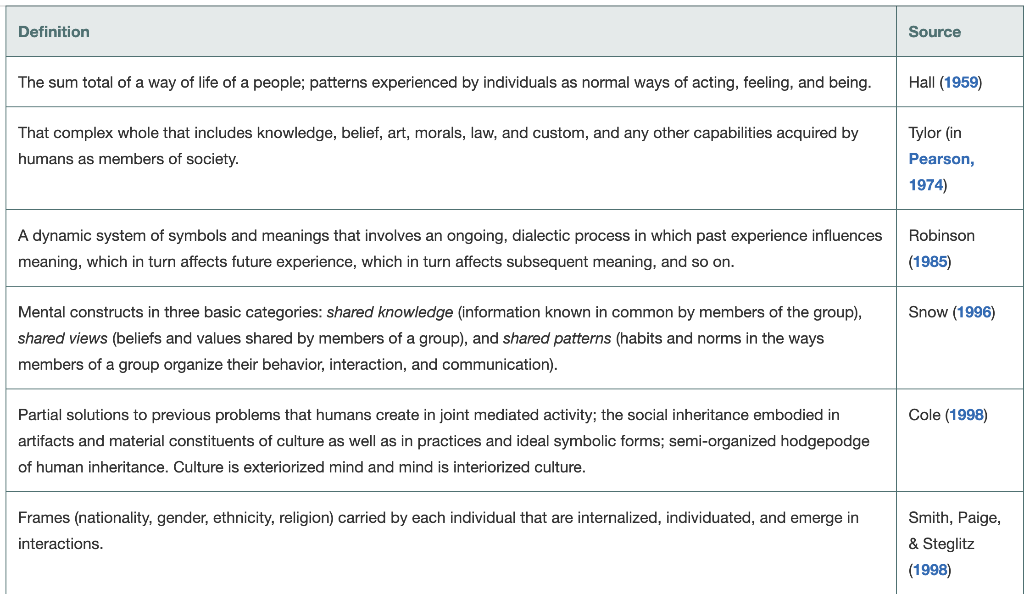

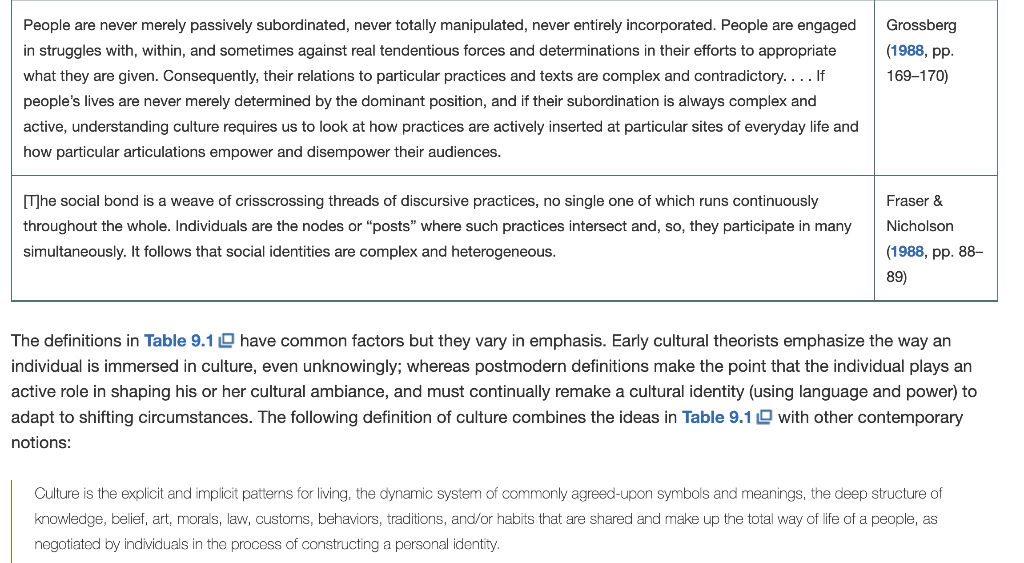

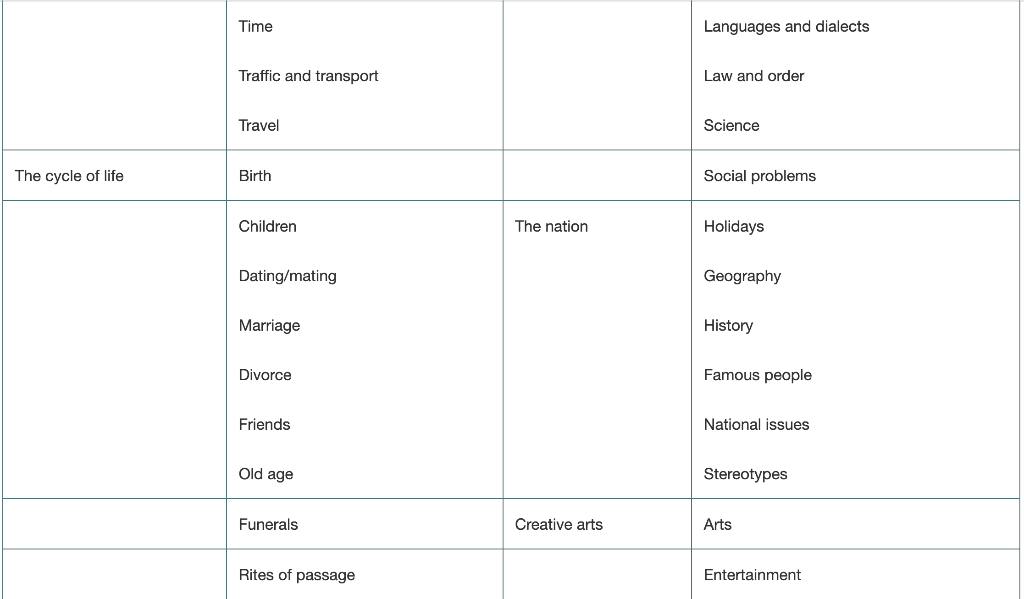

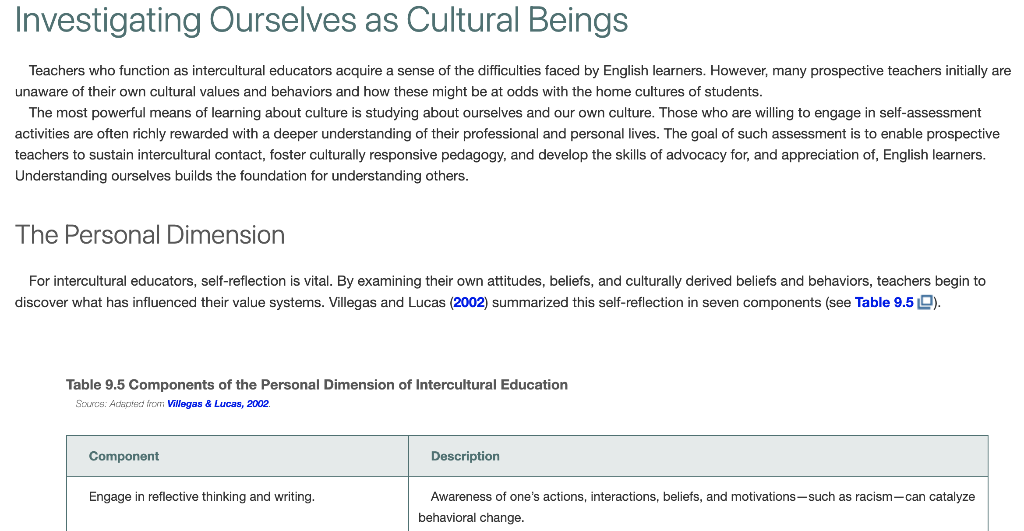

9 Culture and Cultural Diversity and Their Relationship to Academic Achievement Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able to ... Define culture; describe the psychological, sociocultural factors and educational issues that affect English learners; Explain the process of, and the issues surrounding, cultural contact, and possible ways to resolve problems of cultural contact; Characterize in detail the history and demographics of cultural diversity within the United States as well as the historical and contemporary causes of migration and immigration, and the challenges of linguistic and cultural diversity; Depict the ways that intercultural communication, both verbal and nonverbal, is affected by diversity; relate ways that intercultural communication strategies can be used and taught in the classroom; and Investigate oneself as a cultural being by engaging in self-study and growth relationships. Cultural Concepts and Perspectives People used to think of culture as Culture, as in "highbrow" activities such as going to the opera or symphony, or as Exotic Culture, such as viewing a display of African masks. But culture is more than performing traditional rites or crafting ritual objects. Culture, though largely invisible, influences the way people think, talk, and act-the very way people see the world. Cultural patterns are especially evident in schools because home and school are the chief sites where the young are acculturated. If we accept the organization, teaching and learning styles, and curricula of the schools as natural and right, we may not realize that these patterns are cultural; they seem natural and right only to the members of the culture who created them. As children of nondominant cultures enter the schools, however, they may find the organization, teaching and learning styles, and curricula to be alien, incomprehensible, and exclusionary. Fortunately, teachers can learn to see clearly the key role of culture in teaching and learning. They can incorporate culture into classroom activities in superficial ways-as a group of artifacts (baskets, masks, distinctive clothing), as celebrations of holidays (Cinco de Mayo, Martin Luther King Jr. Day), or as a laundry list of stereotypes and insensitivities to be avoided. These ways of dealing with culture are limiting but useful as a starting point. However, teachers can also gain a more insightful view of culture and cultural processes and use this understanding to move beyond the superficial. To be knowledgeable as an intercultural educator is to understand that observable cultural items are but one aspect of the cultural web-the intricate pattern that weaves and binds a people together. Knowing that culture provides the lens through which people view the world, teachers can look at the "what" of a culture-the artifacts, celebrations, traits, and facts - and ask "why?" Knowledge of the deeper elements of culture-beyond aspects such as food, clothing, holidays, and celebrations can give teachers a cross-cultural perspective that allows them to educate students to the fullest extent possible. What Is Culture? Does a fish understand water? Do people understand their own culture? Teachers are responsible for helping to pass on cultural knowledge through the schooling process. Can teachers step outside their own culture long enough to see how it operates and to understand its effects on culturally diverse students? A way to begin is to define culture. Defining Culture The term culture is used in many ways. It can refer to activities such as art, drama, and ballet or to items such as pop music, mass media entertainment, and comic books. The term culture can be applied to distinctive groups in society, such as adolescents and their culture. It can be a general term for a society, such as the "French culture." Such uses do not, however, define what a culture is. As a field of study, culture is conceptualized in various ways (see Table 9.1 ). Definition The sum total of a way of life of a people; patterns experienced by individuals as normal ways of acting, feeling, and being. That complex whole that includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, and custom, and any other capabilities acquired by humans as members of society. A dynamic system of symbols and meanings that involves an ongoing, dialectic process in which past experience influences meaning, which in turn affects future experience, which in turn affects subsequent meaning, and so on. Mental constructs in three basic categories: shared knowledge (information known in common by members of the group), shared views (beliefs and values shared by members of a group), and shared patterns (habits and norms in the ways members of a group organize their behavior, interaction, and communication). Partial solutions to previous problems that humans create in joint mediated activity; the social inheritance embodied in artifacts and material constituents of culture as well as in practices and ideal symbolic forms; semi-organized hodgepodge of human inheritance. Culture is exteriorized mind and mind is interiorized culture. Frames (nationality, gender, ethnicity, religion) carried by each individual that are internalized, individuated, and emerge in interactions. Source Hall (1959) Tylor (in Pearson, 1974) Robinson (1985) Snow (1996) Cole (1998) Smith, Paige, & Steglitz (1998) Grossberg (1988, pp. 169-170) People are never merely passively subordinated, never totally manipulated, never entirely incorporated. People are engaged in struggles with, within, and sometimes against real tendentious forces and determinations in their efforts to appropriate what they are given. Consequently, their relations to particular practices and texts are complex and contradictory.... If people's lives are never merely determined by the dominant position, and if their subordination is always complex and active, understanding culture requires us to look at how practices are actively inserted at particular sites of everyday life and how particular articulations empower and disempower their audiences. Fraser & Nicholson [T]he social bond is a weave of crisscrossing threads of discursive practices, no single one of which runs continuously throughout the whole. Individuals are the nodes or "posts" where such practices intersect and, so, they participate in many simultaneously. It follows that social identities are complex and heterogeneous. (1988, pp. 88- 89) The definitions in Table 9.1 have common factors but they vary in emphasis. Early cultural theorists emphasize the way an individual is immersed in culture, even unknowingly; whereas postmodern definitions make the point that the individual plays an active role in shaping his or her cultural ambiance, and must continually remake a cultural identity (using language and power) to adapt to shifting circumstances. The following definition of culture combines the ideas in Table 9.1 with other contemporary notions: Culture is the explicit and implicit patterns for living, the dynamic system of commonly agreed-upon symbols and meanings, the deep structure of knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs, behaviors, traditions, and/or habits that are shared and make up the total way of life of a people, as negotiated by individuals in the process of constructing a personal identity. To understand culture, one must look beyond the obvious to understand how values, codes, beliefs, and social relations are continually being reshaped by shifting parameters of place, identity, history, and power. Rather than individuals being excluded for differing from cultural norms, people with dissonant, flexible, complex, and hybrid racial and ethnic identities struggle to generate new meanings within accommodating contexts as they use experimentation and creativity to rework existing configurations of knowledge and power and thus extend the possibilities of being human, even in the face of an uncertain outcome. (Daz-Rico, 2013, pp. 263-264) The important idea is that culture involves both observable behaviors and intangibles such as beliefs and values, rhythms, rules, and roles. The concept of culture has evolved over the past fifty years away from the idea of culture as an invisible, patterning force to that of culture as an active tension between the social "shortcuts" that make consensual society possible and the contributions and construction that each individual creates while living in society. To mix metaphors, culture is not only the filter through which people see the world but also the raw dough from which each person fashions a life that is individual and satisfying. Because culture is all-inclusive, it includes multiple aspects of life. Snow (1996) listed a host of components (see Table 9.2 L). Table 9.2 Components of Culture Source: Snow, 1996. Component Component Example Daily life Interacting Chatting Eating Drinking Example Animals Clothing Daily schedule Food Games Hobbies Housing Hygiene Jobs Medical care Plants Recreation Shopping Space Sports Society Gift giving Language learning Parties Politeness Problem solving Business Cities Economy Education Farming Industry Government and politics The cycle of life Time Traffic and transport Travel Birth Children Dating/mating Marriage Divorce Friends Old age Funerals Rites of passage The nation Creative arts Languages and dialects Law and order Science Social problems Holidays Geography History Famous people National issues Stereotypes Arts Entertainment Values Philosophy Literature Religion Music Beliefs Television Key Concepts about Culture To understand culture, one cannot simply total a list of traits-there is wholeness about cultures, with various aspects overlapping and integrated with other aspects. Cultures cannot be taught merely by examining external features such as art and artifacts, although those may be a useful starting point. Even traveling to a country may not engender a deeper understanding of that country's culture(s). To understand a culture, one must examine the living patterns and values of the people living in that culture. Despite the aspects of diverse cultures that may seem unique, cultures have various elements in common. Culture Is Universal Everyone in the world belongs to one or more cultures. Each culture provides organized ways to carry out and interpret such experiences as serving food, speaking to children, marrying, and so forth. Because humans have similar needs, cultures must meet these needs, albeit in diverse ways. Culture Simplifies Living Social behaviors and customs offer structure to daily life that minimizes interpersonal stress. Cultural patterns are routines that free humans from endless negotiation about each detail of living. Culture helps to unify a society by providing a common base of communication and social customs. Culture Is Learned in a Process of Deep Conditioning Cultural patterns are absorbed unconsciously from birth, as well as explicitly taught by other members. The fact that cultural patterns are deep makes it difficult for the members of a given culture to see their own culture as learned behavior. Culture Is Demonstrated in Values, Beliefs, and Behaviors Every culture holds some beliefs and behaviors to be more desirable than others, whether about nature, human character, material possessions, or other aspects of the human condition. Those members of the culture who exemplify these values are rewarded with prestige or approval. Culture Is Expressed Both Verbally and Nonverbally Although language and culture are closely identified, nonverbal components of culture can be just as powerful in communicating cultural beliefs, behaviors, and values. Images, gestures, and emotions are as culturally conditioned as words. In the classroom, teachers may misunderstand a student's intent if nonverbal communication is misinterpreted. Reader Prefe Classroom Glimpse Nonverbal Miscommunication Ming was taught at home to sit quietly when she was finished with a task and wait for her mother to praise her. As a newcomer in the third grade, she waited quietly when finished with her reading assignment. Mrs. Wakefield expected Ming to take out a book to read or to begin another assignment when she completed her work. She made a mental note: "Ming lacks initiative." Societies Represent a Mix of Cultures The patterns that dominate a society form the macroculture of that society. Within the macroculture, a variety of microcultures (subcultures) coexist, distinguished by characteristics such as gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, geographical location, social identification, and language use. Did You Know? Generations of Japanese Immigrants The first generation of Japanese immigrants, who often referred to themselves as issei or first generation, came to the United States starting about 1900. These were, for the most part, young men who worked as agricultural laborers or skilled craftsmen. Often seen as a threat by European Americans, these immigrants were often the targets of discrimination. This prejudice came to a head after the attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor in 1941, when the issei were divested of their property and removed to relocation camps. After the war, their children, the nisei generation, assumed a low ethnic profile, perhaps as a response to the treatment of their parents. (Leathers, 1967) Generational experiences can cause the formation of microcultures. For example, the children of Vietnamese who immigrated to the United States after the Vietnam War often became native speakers of English, although their parents often spoke little English. This separated the two generations by language. Similarly, Mexicans who migrate to the United States may find that their children born in the United States do not consider themselves Mexicans or Mexican American but instead identify with other terms such as Chicano. Most Societies Have a Mainstream Culture The term mainstream culture refers to those individuals or groups who share values of the dominant macroculture. In the United States, the macroculture's traditions and cultural patterns-the mainstream culture-have largely been determined by European Americans who constitute the middle class. Mainstream American culture is characterized by the following values (Gollnick & Chinn, 2013): Individualism and privacy Independence and self-reliance Equality Ambition and industriousness Competitiveness Appreciation of the good life Perception that humans are separate from, and superior to, nature Culture Is Both Dynamic and Persistent Some features of human cultures are flexible and responsive to change, and other features last thousands of years without changing. Values and customs relating to birth, marriage, medicine, education, and death seem to be the most persistent, for humans seem to be deeply reluctant to alter those cultural elements that influence labor and delivery, marital happiness, health, life success, and eternal rest. Culture Is a Mix of Rational and Nonrational Elements Much as individuals living in western European post-Enlightenment societies may believe that reason should govern human behavior, many cultural patterns are . . passed on through habit rather than reason. People who bring a real tree into their houses in December-despite the mess it creates-do because of age-old Yule customs. Similarly, carving a face on a hollow pumpkin or hiding colored eggs are hardly rational activities. Customs persist because they provide human satisfaction, or offer workable solutions to persistent problems, such as assigning postal numbers to houses on a street. Cultures Represent Different Values The fact that each culture possesses its own particular traditions, values, and ideals means that each culture of a society judges right from wrong in a different way. Actions can be judged only in relation to the cultural setting in which they occur. This point of view has been called cultural relativism. In general, the primary values of human nature are universal-for example, few societies condone murder. However, sanctions relating to actions may differ. The Native American cultures of California before contact with Europeans were peace loving to such an extent that someone who took the life of another would be ostracized by the tribe. In contrast, the U.S. macroculture deems it acceptable for soldiers to kill in the context of war. Classroom Glimpse Clashing Values about Reading Fiction Jerome Harvey gave out library prizes in the sixth grade for ROAR (Required Outside Additional Reading). Students competed with one another to see how many pages they could read and report during the contest period. Min-Yi Chen, one of the outstanding readers in class, ranked near the bottom in number of pages. Mr. Harvey brought this up with the Chens at the fall parent-teacher conference. "Well," said Mr. Chen, "Reading of stories is a waste of time-we expect her to go to summer math camp, and the entrance exam is in January. She will be working two or three hours per night on that." Mr. Harvey wonders if he should quit urging Min-Yi to read on her own. Culture Affects People's Attitudes toward Schooling Educational aspiration affects the attitude people have toward schooling, what future job or profession they desire, the importance parents ascribe to education, and how much investment in education they are willing to make. The son of blue-collar workers, for example, might not value a college education because his parents, who have not attained such an education, have nevertheless prospered; whereas the daughter of a recent low-wage immigrant may work industriously in school to pursue higher education and a well-paid job. Cultural values also affect the extent to which families are involved in their children's schooling and the forms this involvement takes. Family involvement is discussed in Chapter 10. Best Practice Working with Aspirations about Schooling In working with English learners, teachers will want to know the following: What educational level does the family and community expect for the student? What understanding do family members have about the connection between educational level attained and career aspiration? What link does the family make between current effort and career aspiration? Culture Governs the Way People Learn Any learning that takes place is built on previous learning. Students have absorbed the basic patterns of living in the context of their families. They have acquired the verbal and nonverbal behaviors appropriate r their gender and age and have observed their family members in various occupations and activities. They have seen community members cooperating to learn in a variety of methods and modes. Their families have given them a feeling for music and art and have shown them what is beautiful and what is not. Finally, they have learned to use language in the context of their homes and communities, and they can express their needs, desires, and delights. The culture that students bring from the home is the foundation for their learning in school. Although certain communities exist in relative poverty-that is, they are not equipped with middle-class resources-poverty should not be equated with cultural deprivation. Every community's culture incorporates vast knowledge about successful living. Teachers can use this cultural knowledge to organize students' learning in schools. Culture appears to influence the way individuals select strategies and approach learning. For example, students who live in a farming community may have sensitive and subtle knowledge about weather patterns, and this may predispose students to value study in the classroom that helps them better understand natural processes such as climate. These students may prefer a kinesthetic style that builds on the same kind of learning that has made it possible for them to sense subtleties of weather. In a similar manner, Mexican American children from traditional families who are encouraged to view themselves as an integral part of the family may prefer social learning activities. Acting and performing are the focus of learning for many African American children. Children observe other individuals to determine appropriate behavior and to appreciate the performance of others. In this case, observing and listening culminates in an individual's performance before others (Heath, 1999). In contrast, reading and writing may be primary learning modes for other cultures. Traditionally educated Asian students equate the printed page with learning and often use reading and writing to reinforce understanding. Despite these varying approaches, all cultures lay out the basic design for learning for their members. Ethnocentrism Versus Cultural Relativism Individuals who grow up within a macroculture and never leave it may act on the assumption that their values are the norm. When encountering other cultures, they may be unable or unwilling to recognize that alternative beliefs and behaviors are legitimate within the larger society. Paige (1999) defined this ethnocentrism as how "people unconsciously experience their own cultures as central to reality. They therefore avoid the idea of cultural difference as an implicit or explicit threat to the reality of their own cultural experience" (p. 22). In contrast, people who accept cultural relativism recognize that all behavior exists in a cultural context, including their own. They understand the limitation this places on their experience, and they therefore seek out cultural diversity as a way of understanding others and enriching their own experience of reality (Paige, 1999). When people adopt a culturally relative point of view, they are able to accept that a different culture might have different operating rules, and they are willing to see that in a neutral way, without having to judge their own culture as inferior or superior by comparison. Cultural Relativism Versus Ethical Relativism Accepting the fact that a person from another culture may have different values does not mean that from a culturally relative point of view one must always agree with the values of a different culture-some cultural differences may be judged negatively-but the judgment is not ethnocentric in the sense of denying that such a difference could occur. Cultural relativism is not the same as ethical relativism-saying "cultures have different values" is not the same as saying "morally and ethically, anything goes" (all behavior is acceptable in all contexts). One does not have to abandon one's own cultural values to appreciate the idea that not all cultures share the same values. Cultural Pluralism The idea that a society can contain a variety of cultures is a pluralist viewpoint. There are two kinds of pluralist models-pluralist preservation holds that a society should preserve all cultures intact, with diversity and unity as equal values, whereas pluralistic integration is the belief that society should have consensus about core civic values. Both these positions contrast with the idea that a society should be composed of a monoculture, with all diversity assimilated (the "melting pot" model). Individually, some people are bicultural, able to shift their cultural frames of reference and intentionally change their behavior to communicate more effectively when in a different culture. However, just because people are raised in two cultures does not necessarily give them the ability to understand themselves or to generalize cultural empathy to a third culture. Even in a society in which members of diverse cultural groups have equal opportunities for success, and in which cultural similarities and differences are valued, ethnic group identity differences may lead to intergroup conflict. A dynamic relationship between ethnic groups is inevitable; each society must find healthy ways to mediate conflict. The strength of a healthy society is founded on a basic willingness to work together to resolve conflicts. Schools can actively try to foster interaction and integration among different groups. Integration creates the conditions for cultural pluralism. Cultural Congruence In U.S. schools, the contact of cultures occurs daily. Students from families whose cultural values are similar to those of the European American mainstream culture may be relatively advantaged in schools, such as children from those Asian cultures who are taught that students sit quietly and attentively-behavior that is rewarded in most classrooms. In contrast, African American students who learn at home to project their personalities and call attention to their individual attributes (Gay, 1975) may be punished for acting out. The congruence or lack thereof between mainstream and minority cultures has lasting effects on students. Teachers, who have the responsibility to educate students from diverse cultures, find it relatively easy to help students whose values, beliefs, and behaviors are congruent with U.S. schooling but often find it difficult to work with others. The teacher who can find a common ground with diverse students will promote their further education. Relationships between individuals or groups of different cultures are built through commitment, enjoyment of diversity, and a willingness to communicate. The teacher, acting as intercultural educator, accepts and promotes cultural content in the classroom as a valid and vital component of the instructional process and helps students to achieve within the cultural context of the school. Classroom Glimpse Schooling in Vietnam American schools may be a shock for children-and for parents who have immigrated from Vietnam. In Vietnam children go to school six days a week for about five hours. In most subjects, students are taught by means of rote learning. There is a strong emphasis on moral and civic education, especially the behavior expected of a socialist citizen. Most schools have no playground equipment or extracurricular activities. Teachers are required to pay for classroom supplemental materials themselves, such as art supplies. The high school curriculum is college-entry-examination oriented. Source:http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Vietnam/sub5_9f/entry-3458.html The Impact of Physical Geography on Cultural Practices A social group must develop the knowledge, ideas, and skills it needs to survive in the kind of environment the group inhabits. The geographical environment or physical habitat challenges the group to adapt to or modify the world to meet its needs. When the Native Americans were the sole inhabitants of the North American continent, wide variety of cultures existed, a necessary response to the variety in the environment. The Iroquois were a village people who lived surrounded by tall wooden palisades. The Chumash, in contrast, had a leisurely seashore existence on the California coast where fishing was plentiful and the climate moderate. Still a third group, the Plains Indians, were a nomadic people who followed the bison. Each group's culture was adapted for success in its own specific environment. Classrooms constitute physical environments. These environments have an associated culture. In a room in which the desks are in straight lines facing forward, participants are acculturated to listen as individuals and to respond when spoken to by the teacher. This may be a difficult environment for a young Pueblo child whose learning takes place largely in the communal courtyards outside comfortable adobe dwellings and who is taught traditional recipes by a mother or grandmother or the secrets of tribal lore in an underground kiva by the men of the village. The physical environments in which learning takes place vary widely from one culture to another. Intragroup and Intergroup Cultural Differences Even among individuals from the same general cultural background, there are intragroup differences that affect their worldviews. Some student populations have very different cultures despite a shared ethnic background. Such is the case at Montebello High School in the Los Angeles area: Students at Montebello ... may look to outsiders as a mostly homogeneous population-93 percent Latino, 70 percent low-income-but the 2,974 Latino students are split between those who are connected to their recent immigrant roots and those who are more Americanized. On the "TJ" (for Tijuana) side of the campus, students speak Spanish, take ESL classes, and participate in soccer, folklorico dancing, and the Spanish club. On the other side of campus, students speak mostly English, play football and basketball, and participate in student government. The two groups are not [mutually] hostile... but, as senior Lucia Rios says, "it's like two countries." The difference in values between the two groups stems from their families' values-the recent immigrants are focused on economic survival and do not have the cash to pay for extracurricular activities. Another difference is musical taste (soccer players listen to Spanish music in the locker room, whereas football players listen to heavy metal and rap). (Hayasaki, 2004, pp. A1, A36-A37) In the preceding example, the immigrants who had arrived within the last three to five years still referred to Mexico as home. Most of these students were monolingual in Spanish, with varying levels of English proficiency. In contrast, the U.S.-born Mexican American students were English speakers-although they had Mexican last names, they were strongly acculturated into mainstream U.S. values and manifested few overt Mexican cultural symbols. Each of these groups could be considered a microculture within the larger microculture of people of Mexican descent living within the United States. In this case, social identification and language usage, as well as dress, were the markers of the distinct microcultures. As immigrants enter American life, they make conscious or unconscious choices about which aspects of their culture to preserve and which to modify. These decisions are a response to cultural contact. Looking at Culture from the Inside ut External Elements of Culture External elements of culture (e.g., shelter, clothing, food, arts and literature, religious structures, government, technology, language) are relatively easily identified as cultural markers. Certainly young immigrant children would feel comfortable if external elements of their home culture were prominently displayed in the classroom or school. A display of Mexican-style paper cutouts as decoration in a classroom, for example, usually would be viewed in a positive way and not as a token of superficial cultural appropriation. Indeed, external elements of culture are visible and obvious, to the extent that these are often used as symbols of cultural diversity. How many times does a printed flyer for a Chinese guest speaker have to display a bamboo border before this becomes hackneyed? These visible markers are "ethnic," as in ethnic food." When one goes out for "ethnic food," does one eat roast beef and potatoes-quintessentially British food? When these external symbols are marked only for minorities, the mainstream culture thinks of itself as "culturally neutral," whereas those displaying external elements of microcultures are considered "ethnic." Thus, European American culture is maintained as the norm. Internal Elements of Culture Internal elements of culture (e.g., values, customs, worldview, mores, beliefs and expectations, rites and rituals, patterns of nonverbal communication, social roles and status, gender roles, family structure, patterns of work, and leisure) are harder to identify as cultural markers because they are intangible. Yet these can be as persistent and emotionally loaded as external symbols such as flags or religious icons. In fact, behaviors and attitudes that are misinterpreted can be considered potentially more damaging than misunderstandings about overt symbols, especially with people from cultures that are skilled in reading subtle behavior signals. Classroom Glimpse Can't You Tell I'm Bored? In an English-language development (ELD) class with beginning middle school English learners, Iris Schaffer pointed to a picture with birds on a tree. "Is this a bird or a tree?" she asked. "How many leaves are there on the ground? What is the color of the leaves?" From the student's facial expressions and voice tones, visitor noted that they were bored and showed little interest in learning. To be asked these types of questions at their age could be insulting. The question was, why didn't the teacher know the students were bored? Were their behaviors and attitudes too subtle for the teacher to read? Was she unable to decipher these internal elements of culture? Source: Adapted from Fu, 2004, pp. 9-10 Cultural Diversity: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives The rhetoric seeking to explain school failure of minority children has changed over the years. Because racial explanations have largely failed-although even as late as the turn of the twenty-first century, several psychologists tried to resurrect racial inferiority theory-there have been attempts to find other explanations based more on cultural than racial differences. From Racial Inferiority to Cultural Inferiority Binet's research on intelligence at the turn of the twentieth century, researchers became convinced that inherited racial differences were an explanation for the differential success of students. This became a rationale for unequal school facilities. The genetic inferiority argument, now discredited, assumes that certain populations do not possess the appropriate genes for high intellectual performance. After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision officially signaled the end of segregated schools, the continued lack of school achievement on the part of racial minorities in the United States was attributed not to racial differences but to the fact that families originating in poor, working-class, urban areas were holders of a culture that was inherently inferior. This was a cultural deprivation or cultural deficit model-essentially, it blamed the poor for the lack of resources in the home. Conveniently, it could be used to blame cultural minorities as well as racial minorities. Cultural Incompatibility Theory The next theory, cultural incompatibility or cultural mismatch, denied the implication of an inherent inferiority in minority cultures but posited that the difference in home culture versus school culture was one of the reasons minority students do poorly (Irvine, 1990). The cultural mismatch perspective maintains that cultures vary, and that some of the skills learned in one culture may transfer to a second, but that other skills will be of little value or, worse, interfere with assimilation to the new culture. Cultural mismatch was quickly generalized from its origin in race theory to all cultural differences, including those involving language. Unlike cultural deprivation theory, it placed no explicit value judgment on the culture of either the school or the home, merely stating that when teachers and students do not share the same culture, the different cultural behaviors performed by the other are open to misinterpretation because neither party realizes they may be operating on different cultural codes. Yet the implication was that students from cultures most like those of European Americans would do well in school, students from noncongruent cultures would not. The concept that minority students experience a cultural dissonance between their home and school culture is well documented (Heath, 1999). Unfortunately, this theory has left the onus on teachers to change conditions within the classroom to accommodate the students' cultures, which has proved to be difficult when students from many cultures are schooled in the same room. The result has been "business as usual," with the culture of the schools remaining intact along with the expectation that the culture of the home will change. The Contextual Interaction Model Another explanation posits that achievement is a function of the interaction between two cultures. The contextual interaction model states the values of each are not static but instead adapt to one another when contact occurs. This is the origin of the idea that teachers should accommodate instruction to students as they acculturate. Issues of Power and Status In classrooms during the monolingual era, students spoke one language or remained silent. The institution controlled the goals and purposes of students' second-language acquisition. There was no question who had the power-the teacher, the authorities, and the language sanctioned by the school (McCarty, 2005). As for theories of cultural incompatibility, in retrospect these were too narrowly focused on the student, the school, and the home, ignoring the larger issue of inequity of resources in society. The "cure" for school failure in the cultural dissonance model was to align the cultures of the home and school more congruently- and because teachers and schools could not accomplish that mission in the short time allotted for teacher multicultural education, the burden was put again to the families to assimilate more rapidly. Hence the classic emphasis put on the individual to transcend his or her social class. As soon as the limitations of this liberalist model became apparent, a conservative federal administration instituted rigorous testing, setting into motion the specter of failure not only for individuals but also for entire schools in minority communities. This distracted schools from the mission of cultural congruence and left the issues unresolved, emphasizing instead standardized testing. The Impact of Ethnic Politics In the postmodern shift, power circulates, just as dual-language acquisition circulates power between peoples and among cultures. Instead of the pretense that power is nonnegotiable, unavailable, and neutral, communities sought to gain the power to speak, to use public voice for their self-determined ends. This resulted in the movement toward charter schools, by which families can choose to exit the public schools. Some charter schools have done a better job than the public schools of fostering ethnic pride. One student from a small middle school in Oakland, California, put it this way: It was just really like a community setting... like we were learning at home... with a bunch of our friends. They had really nice teachers who were, you know, mostly Chicano and Chicana. . We could relate to them. They know your culture, your background. [They] talk to your parents and your parents trust them. It's like a family. The pursuit of local schools that reflect the values of the parent community has led to serious alternatives to the dream of the public school that can educate all children with equity under one roof. Many advocates of charter schools no longer believe that the children of diversity can wrest a high-quality education from neighborhood schools that are underfunded and mediocre. The notion of empowerment has taken many ethnic communities down the path of separatism (Fuller, 2003). Overall, charter schools have proven to be of mixed success. Political and Socioeconomic Factors Affecting English Learners and Their Families By the year 2010-ten years into the new millennium-one of every three Americans was African American, Hispanic American, or Asian American. This represents a dramatic change from the image of the United States throughout its history. Immigration, together with differing birthrates among various populations, is responsible for this demographic shift. Along with the change in racial and ethnic composition has come a dramatic change in the languages spoken in the United States as well as the languages heard in U.S. schools. These changing demographics are seen as positive or negative depending on one's point of view. Some economists have found that immigrants contribute considerably to the national economy by filling low-wage jobs, spurring investment and job creation, revitalizing once-decaying communities, and paying billions annually in taxes. Unfortunately, the money generated from federal taxes is not returned to the local communities most affected by immigration to pay for schools, hospitals, and social services needed by newcomers. The resultant stress on these services may cause residents to view newcomers negatively. In the midst of changing demographics in the United States, immigrants and economically disadvantaged minorities within the country face such challenges as voting and citizenship status; family income, employment, and educational attainment; housing; and health care availability. Culture and Gender Issues Parents of English learners often work long hours outside the home, and some families simply are unable to dedicate time each evening to help students complete school assignm Many young people find themselves working long hours outside the home help support the family or take care of while parents work double shifts. The role of surrogate caretaker often falls disproportionately on young women, compromising their academic potential. Some immigrant families favor the academic success of sons over daughters, to the dismay of teachers in the United States who espouse equality of opportunity for women. This issue may be more acute as high school students contemplate attending college. Other issues have emerged as immigrants enter U.S. schools from ever more diverse cultures. Some girls from traditional cultures are forbidden by their families to wear physical education attire that reveals bare legs. Male exchange students from Muslim cultures may be uncomfortable working in a mixed-gender cooperative learning group in the classroom. Parents who have adopted children from the People's Republic of China may request heritage-language services from the local school district. Multiple issues of language and culture complicate schooling for English learners. Poverty among Minority Groups A key difficulty for many minorities is poverty. In 2016, almost one-quarter (22 percent) of African Americans and 19 percent of Hispanic Americans lived in poverty, compared with Whites at 8.8 percent (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Poverty hits minority children particularly hard. In 2016, 41 percent of the 72.4 million children in the United States who were age eighteen or under lived in poverty (about 30 million children). In percentages, 35 percent of poor children are White, 24 percent are Black, and 36 percent are Hispanic (Koball & Jiang, 2018). The Children's Defense Fund (2017) reports that 31 percent of Black children live under the poverty line, and 27 percent of Hispanic children are poor. Poverty does not mean merely inadequate income; rather, it engenders a host of issues, including underemployment, insufficient income and jobs with limited opportunity, homelessness, lack of health insurance, inadequate education, and poor nutrition. Poor children are at least twice as likely as nonpoor children to suffer stunted growth or lead poisoning or to be kept back in school. They score significantly lower on reading, math, and vocabulary tests when compared with similar nonpoor children (Children's Defense Fund, 2017). However, not all poverty can be linked to these difficulties; some minorities continue in poverty because of social and political factors in the country at large, such as racism and discrimination. Poverty affects the ability of the family to devote resources to educational effort and stacks the deck against minority-student success. Demographic trends ensure that this will be a continuing problem in the United States. Almost three-quarters (74.0 percent) of the Hispanic population is under thirty-five years of age, compared with a little more than half (51.7 percent) of the non-Hispanic White population. The average Hispanic female is well within childbearing age, and Hispanic children constitute the largest growing school population. Therefore, the educational achievement of Hispanic children is of particular concern. Educational Issues Involving English Learners Beyond the Classroom What obligation does a community have toward non-English-speaking children? When education is the only means of achieving social mobility for the children of immigrants, these young people must be given the tools necessary to participate in the community at large. When school dropout rates exceed 50 percent among minority populations, it seems evident that the schools are not providing an adequate avenue of advancement. Clearly, some English learners do succeed: Asian American students are overwhelmingly represented in college attendance, whereas Hispanics are underrepresented. Individual states are addressing the obligation to educate all students by adhering to content standards documents, such as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Nevertheless, children continue to receive different treatment in public schools. The structure of schooling creates equity problems, all the way from segregative tracking procedures to the day-to-day operation of classrooms, in which some students' voices are heard while others are silenced. These structural components of schools must be addressed lest the belief continue that achievement problems reside solely within students. In schools, underachievement, the "overachievement" myth, segregation, overreferral to special education, lack of access to the core curricula, and little support for the home language are key concerns. These phenomena may occur because of the ways in which schools and classrooms promote unequal classroom experiences for students. In response to the perception that some students underachieve or overachieve or drop out or are pushed out, schools have designed various mechanisms to help students succeed. Some of these have been successful, others problematic. The economy of the United States in the future will rest more on Asian American and Hispanic American workers than at present. As a consequence, the education of these populations will become increasingly important. Consider that in 2014, 47 percent of students enrolled in public elementary and secondary schools were minorities-an increase of 21 percent from 2000, largely due to the growth in the Hispanic population (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2017b). Of these minorities, 89.1 percent of Asian Americans have a high school degree and 53.9 percent have bachelor degrees or higher. In contrast, only 66.7 percent of Hispanics have high school diplomas and 15.5 percent have college degrees or higher, whereas 88.8 percent of non-Hispanic Whites have high school diplomas and almost one third (32.8 percent) have bachelor degrees (Ryan & Bauman, 2016). With these numbers, the extent of the problem becomes clearer. Underachievement-Retention, Placement, and Promotion Policies Unfortunately, some students are at risk of grade retention due to underachievement almost immediately on entering school. In 2015, higher overall percentages of Black students (3.0 percent) and Hispanic students (2.9 percent) than of White students (1.8 percent) were retained in kindergarten through twelfth grade (Musu- Gillette, Robinson, McFarland, KewalRamani, Zhang, & Wilkinson-Flicker, 2016), despite the fact that numerous studies have cast doubt on the usefulness of grade retention (see Cordes, 2016, for a review of this literature). However, English learners (ELS) fared far worse: In every grade except kindergarten, ELs were overrepresented among the students retained in grade at the end of the school year. A larger proportion of the students retained at grade level were ELs, compared to the proportion of ELs enrolled (e.g., 13 percent compared with 10 percent). The overrepresentation of English leamers among retained students was largest in high school.... For example, in 2011-12, the EL percentage of all students retained in 12th grade (11 percent) was more than twice the EL percentage of students enrolled in 12th grade (5 percent). (U.S. Department of Education Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development Policy and Program Studies Service, 2016, p. 2). Thus, ELs are much more at risk of school retention than other students. This causes a corresponding hit on graduation rates: ELs' graduation rate (59 percent) is much lower than non-ELs (82 percent). On the other side of the coin, English learners are also differentially distributed in advanced placement courses, thus failing to achieve a type of "in-house" promotion. Tracking offers very different types of instruction depending on students' placement in academic or general education courses. To justify this, educators have argued that tracking is a realistic, efficient response to an increasingly diverse student population. However, tracking has been found to be a major contributor to the continuing gaps in achievement between minorities and European Americans (Oakes, 1992). Underachievement-ELD as Compensatory Education The impetus behind the success of the original Bilingual Education Act was that language-minority students needed compensatory education to remediate linguistic "deficiencies." However, compensatory programs are often reduced in scope, content, and pace, and students are not challenged enough, nor given enough of the curriculum to be able to move to mainstream classes. The view that ELD is compensatory education is all too common. As a part of ELD programs, a portion of the instructional day is usually reserved for ELD instruction. Too often the ELD instruction is given by teaching assistants who have not had professional preparation in ELD teaching, and the instruction has consisted of skill-and-drill worksheets and other decontextualized methods. Inclusion of English learners in mainstream classrooms and challenging educational programs is now the trend. In a study of good educational practice for English learners, research has found numerous schools that have successfully been educating these students to high standards (McLeod, 1995). In these schools, programs for English learners were an integral part of the whole school program, neither conceptually nor physically separate from the rest of the school. The exemplary schools have devised creative ways to both include English learners centrally in the educational program and meet their needs for language instruction and modified curriculum. Programs for English learners are so carefully crafted and intertwined with the school's other offerings that it is impossible in many cases to point to "the LEP [limited-English proficient[ program" and describe it apart from the general program (McLeod, 1995). Several reform efforts have attempted to dismantle some of the compensatory education and tracking programs previously practiced in schools. These have included accelerated sch cooperative restructured scho and "detracking." A particularly noteworthy high school program is Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID). This "detracking" program places low-achieving students (who are primarily from low-income and ethnic or language-minority backgrounds) in the same college preparatory academic program as high-achieving students (who are primarily from middle- or upper-middle-income and "Anglo" backgrounds). Use a search engine to explore the AVID model. Underachievement-Dropping Out of High School An unfortunate and direct result of being schooled in an unfamiliar language is that some students begin falling behind their expected grade levels, eventually putting them at risk. Students who repeat at least one grade are more likely to drop out of school. Every year across the country, a dangerously high percentage of students-disproportionately poor and minority-disappear from the educational pipeline before graduating from high school. Nationally, only about 68 percent of all students who enter ninth grade will graduate "on time" with regular diplomas in twelfth grade. Whereas the graduation rate for White students is 75 percent, only approximately half of Latino students earn regular diplomas alongside their classmates. Even though California reports a robust overall graduation rate of 86.9 percent, researchers at the Harvard Civil Rights Project have claimed that this figure dramatically underestimates the actual numbers of dropouts and that graduation rates in individual districts and schools-particularly those with high minority concentrations- remain at crisis-level proportions. Recent research reveals disturbing dropout rates for minorities in the United States. Seven states had the worst graduation rates for Hispanic/Latino students in 2012-2013: Minnesota (59 percent), Oregon (60.8 percent), New York (62.3 percent), Georgia (62.6 percent), Nevada (64.4 percent), Colorado (65.4 percent), and Washington (65.9 percent) (the national rate was 75 percent) (Wong, 2015). In 2016, Los Angeles Unified School District recorded a 77 percent graduate rate for Latinos, in contrast with 88 percent for Whites and 93 percent for Asians (one source, however, attributed this rate to an array of "credit recovery" programs, in which students can make up missing credits quickly) (Kohli, 2017). Despite a California state graduation rate of 83.2 percent in 2016, just 62 percent of California State University freshmen were considered college-ready in both English and math. Disappointing graduate rates suggest that Hispanics will be underrepresented in higher education for years to come. An important marketplace repercussion from dropout statistics is the differential rate of employment of these two groups: In 2014, about 70 percent of high school dropouts were in the labor force versus 85 percent of graduates who were enrolled in college (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). The Hispanic Dropout Project (1998) explicated the continuing stereotypes, myths, and excuses that surround Hispanic-American youth and their families: What we saw and what people told us confirmed what well-established research has also found: Popular stereotypes-which would place the blame for school dropout on Hispanic students, their families, and language background, and would allow people to shrug their shoulders f to say that t was an enormous, insoluble problem or one that would go away by itself-are just plain wrong. (p. 3) The Hispanic Dropo