Question: Question: Write a 6- to 12-sentence paragraph summarizing how installing solar panels on California Canals can reduce greenhouse gas emissions (don't talk about other alternatives,

Question:

Write a 6- to 12-sentence paragraph summarizing how installing solar panels on California Canals can reduce greenhouse gas emissions (don't talk about other alternatives, focus is on Solar panels on California Canals). Use both sources I've provided below; no other sources should be used. You must use my sources below to prove your point and claim. Make your answer as specific as possible. Thanks.

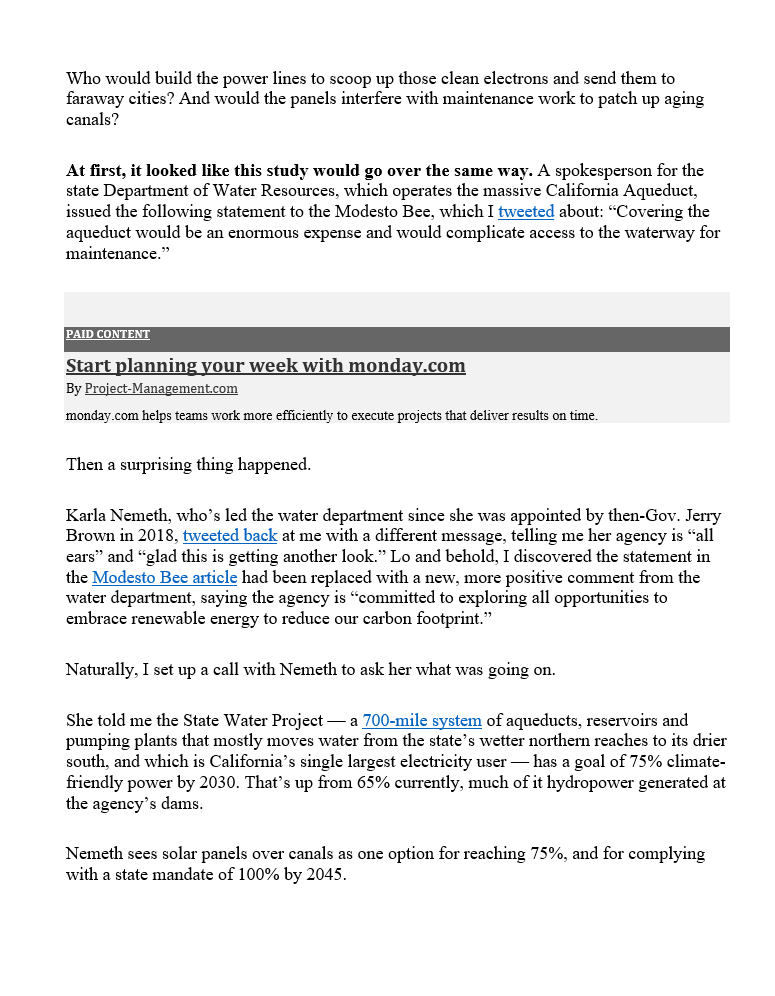

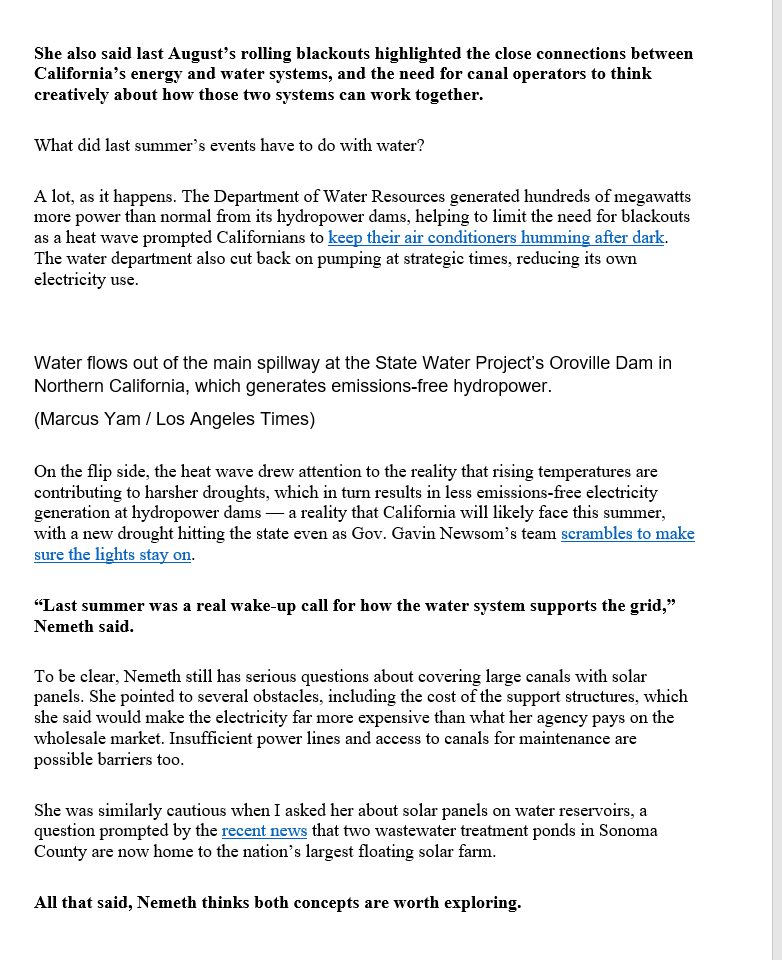

Conserving water and land such system in the world. We estimate that about 1%-2% of the water they carry is lost to evaporation under the hot California sun. Climate change and water scarcity are front and center in the western U.S. The region's climate is warming, a severe multi-year drought is underway and groundwater supplies are being overpumped in many locations Western states are pursuing many strategies to aclapt to these stresses and prepare for the future. These include measures to promote renewable energy development, conserve water, and manage natural and working lands more sustainably. As engineers working on climate-smart solutions, we've found an easy wir win for both water and climate in California with what we call the "solar canal solution." About 4,000 miles of canals transport water to some 35 million Californians and 5-7 million acres of farmland across the state. Covering these canals with solar panels would reduce evaporation of precious water - one of California's most critical resources - and help meet the state's renewable energy goals, while also saving money. California is prone to drought, and water is a constant concern. Now, the changing climate is bringing hotter, drier weather. In a 2021 study, we showed that covering all 4,000 miles of California's canals with solar panels would save more than 65 billion pallons of water annually by reducing evaporation. That's enough to irrigate 50,000 acres of farmland or meet the residential water needs of more than 2 million people. By concentrating solar installations on land that is already being used, instead of building them on undeveloped land, this approach would help California meet its sustainable management goals for both water and land resources. Climate-friendly power Shading California's canals with solar panels would generate substantial amounts of electricity. Our estimates show that it could provide some 13 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity, which is about half of the new sources the state needs to add to meet its clean electricity goals: 60% from carbon-free sources by 2030 and 100% renewable by 2045. Installing solar panels over the canals makes both systems more efficient. The solar panels would reduce evaporation from the canals, especially during hot California summers. And because water heats up more slowly than land, the canal water flowing beneath the panels could cool them by 10 F, boosting production of electricity by up to 3%. Severe droughts over the past 10 to 30 years dried up wells, caused officials to implement water restrictions and fueled massive wildfires. As of mid-April 2021, the entire state was officially experiencing drought conditions. These panels could also generate electricity locally in many parts of California, lowering both transmission losses and costs for consumers. Combining solar power with battery storage can help build microgrids in rural areas and underserved communities, making the power system more efficient and resilient. This would mitigate the risk of power losses due to extreme weather, human crror and wildfires. At the same time, California has ambitious conservation goals. The state has a mandate to reduce groundwater pumping while maintaining reliable supplies to farms, cities, wildlife and ecosystems. As part of a broad climate change initiative, in October 2020 Gov. Gavin Newsom directed the California Natural Resources Agency to spearhead efforts to conserve 30% of land and coastal waters by 2030. Most of California's rain and snow falls north of Sacramento during the winter, while 80% of its water use occurs in Southern California, mostly in summer. That's why canals snake across the state - it's the largest We estimate that the cost to span canals with solar panels is higher than building ground-mounted systems. But when we added in some of the co- benefits, such as avoided land costs, water savings, aquatic weed mitigation and enhanced PV efficiency, we found that solar canals were a better investment and provided electricity that cost less over the life of the solar installations, Bencfits to the land shade from the panels limits growth of weeds that block drains and restrict water flow. Solar canals are about much more than just generating renewable energy and saving water. Building these long, thin solar arrays could prevent more than 80,000 acres of farmland or natural habitat from being converted for solar farms, Fighting these weeds with herbicide and mechanical equipment is expensive, and herbicides threaten human health and the environment. For large, 100-foot-wide canals in California, we estimate that shading canals would save about US,000 per mile. Statewide, savings could reach million per year. Bringing solar canals to California California grows food for an ever-increasing global population and produces more than 50% of the fruits, nuts and vegetables that U.S. consumers eat. However, up to 50% of new renewable energy capacity to meet decarbonization goals could be sited in agricultural areas, including large swaths of prime farmland. Solar canal installations will also protect wildlife, ecosystems and culturally important land. Large-scale solar developments can result in habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, which can harm threatened species such as the Mojave Desert tortoise. While India has built solar arrays over canals and the U.S. is developing floating solar projects, California lacks prototypes to study locally. They also can harm desert scrub plant communities, including plants that are culturally important to indigenous tribes. As an example, construction of the Genesis Solar Energy Center in the Sonoran and Mojave deserts in 2012-2014 destroyed trails and burial sites and damaged important cultural artifacts, spurring protracted legal conflict. (Get the best of the Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.) Discussions are underway for both large and small demonstration projects in the Central Valley and Southern California. Building prototypes would help operators, developers and regulators refine designs, assess environmental impacts, measure project costs and benefits, and evaluate how these systems perform. With more data, planners can map out strategies for extending solar canals statewide, and potentially across the West. [You're smart and curious about the world. So are the Conversation's authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.] It will take a dozen or more partners to plan, fund and carry out a solar canal project in California. Public-private partnerships will likely include federal, state and local government agencies, project developers and university researchers, Clearing the air By generating clean electricity, solar canals can improve air quality - a serious problem in central California, which has some of the dirtiest air in the U.S. Solar electricity could help retire particulate-spewing diesel engines that pump water through California's agricultural valleys. It also could help charge growing numbers of electric light- and heavy-duty vehicles that move people and goods around the state. Yet another benefit would be curbing aquatic weeds that choke canals. In India, where developers have been building solar canals since 2014, California's aging power infrastructure has contributed to catastrophic wildfires and multi-day outages. Building smart solar developments on canals and other disturbed land can make power and water infrastructure more resilient while saving water, reducing costs and helping to fight climate change. We believe it's a model that should be considered across the country - and the planet. Solar panels on California's canals could save water and help fight climate change in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. By virtue of the fact that you're reading this newsletter, you're probably aware today is Earth Day or as environmental reporters know it, The day we get even more press releases than usual, but we keep doing the same job we've been doing all year. So I don't have a special Earth Day edition of Boiling Point for you. I do, however, have some intriguing information about an idea that always seems to gets folks excited: Putting solar panels over water. I was initially skeptical when I read about a new study from researchers at UC Merced, finding that covering thousands of miles of California's largest canals with solar panels could generate huge amounts of clean energy at a reasonable cost, while saving lots of water by reducing evaporation. Published in the journal Nature Sustainability, the study concluded that the "net present value of canal-spanning solar systems could be as much as 50% higher than solar farms on nearby land. ADVERTISING Don't get me wrong at an intuitive level, it makes perfect sense. Install photovoltaic panels atop canals, and avoid the land-use battles over habitat protection and rural community character that are a growing roadblock for the solar industry. Save water in a drought-prone state that can use every last drop. Maybe even improve air quality in the notoriously smoggy Central Valley by using the newly installed clean energy infrastructure, paired with batteries, to replace diesel-powered irrigation pumps. A rendering shows what the California Aqueduct would look like covered with solar panels as it flows through Stanislaus County. But when I'd heard these ideas floated in the past, I'd also heard skepticism from the people who run California's water systems. How much would all that solar power cost? Who would build the power lines to scoop up those clean electrons and send them to faraway cities? And would the panels interfere with maintenance work to patch up aging canals? At first, it looked like this study would go over the same way. A spokesperson for the state Department of Water Resources, which operates the massive California Aqueduct, issued the following statement to the Modesto Bee, which I tweeted about: "Covering the aqueduct would be an enormous expense and would complicate access to the waterway for maintenance." PAID CONTENT Start planning your week with monday.com By Project Management.com monday.com helps teams work more efficiently to execute projects that deliver results on time. Then a surprising thing happened. Karla Nemeth, who's led the water department since she was appointed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018, tweeted back at me with a different message, telling me her agency is "all ears and glad this is getting another look. Lo and behold, I discovered the statement in the Modesto Bee article had been replaced with a new, more positive comment from the water department, saying the agency is committed to exploring all opportunities to embrace renewable energy to reduce our carbon footprint." Naturally, I set up a call with Nemeth to ask her what was going on. She told me the State Water Project - a 700-mile system of aqueducts, reservoirs and pumping plants that mostly moves water from the state's wetter northern reaches to its drier south, and which is California's single largest electricity user has a goal of 75% climate- friendly power by 2030. That's up from 65% currently, much of it hydropower generated at the agency's dams. Nemeth sees solar panels over canals as one option for reaching 75%, and for complying with a state mandate of 100% by 2045. She also said last August's rolling blackouts highlighted the close connections between California's energy and water systems, and the need for canal operators to think creatively about how those two systems can work together. What did last summer's events have to do with water? A lot, as it happens. The Department of Water Resources generated hundreds of megawatts more power than normal from its hydropower dams, helping to limit the need for blackouts as a heat wave prompted Californians to keep their air conditioners humming after dark. The water department also cut back on pumping at strategic times, reducing its own electricity use. Water flows out of the main spillway at the State Water Project's Oroville Dam in Northern California, which generates emissions-free hydropower. (Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) On the flip side, the heat wave drew attention to the reality that rising temperatures are contributing to harsher droughts, which in turn results in less emissions-free electricity generation at hydropower dams a reality that California will likely face this summer, with a new drought hitting the state even as Gov. Gavin Newsoms team scrambles to make sure the lights stay on. "Last summer was a real wake-up call for how the water system supports the grid, Nemeth said. To be clear, Nemeth still has serious questions about covering large canals with solar panels. She pointed to several obstacles, including the cost of the support structures, which she said would make the electricity far more expensive than what her agency pays on the wholesale market. Insufficient power lines and access to canals for maintenance are possible barriers too. She was similarly cautious when I asked her about solar panels on water reservoirs, a question prompted by the recent news that two wastewater treatment ponds in Sonoma County are now home to the nation's largest floating solar farm. All that said, Nemeth thinks both concepts are worth exploring. "We do have a need to reinvest in the State Water Project, so we should do it with a mentality and understanding of the challenges that are coming at us, one of which is climate and energy," she said. The idea for the UC Merced study came from a Berkeley-based marketing firm called Citizen Group, whose principals are trying to put the solar canals idea into action. They've started a company called Solar AquaGrid LLC that's looking to develop pilot projects with smaller water agencies that operate their own canals. If and when that happens, expect a story from me. There's no question more research and testing is needed. Not many solar canal systems have been built, meaning the researchers largely relied on a few projects in India for cost estimates. The study's projected water savings of 200,000 acre-feet annually is almost certainly an overestimate, since it assumes 4,000 miles of large canals would be covered with solar, which isn't likely. The same is true of the estimated 13 gigawatts of solar energy, which would equal one-sixth of the state's current power capacity. At the same time, the study didn't capture all the potential benefits of canal-spanning solar canopies, according to Roger Bales, an engineering professor at UC Merced and one of the authors. Replacing pollution-spewing diesel pumps in the Central Valley, which the researchers didn't explore in detail, could improve public health. Keeping some amount of undisturbed land from getting paved over with solar panels could protect biodiversity and support Newsoms 30 by 30" goal to shield nearly one-third of California's land and waters from development by 2030. The economics are attractive because of the multiple benefits," Bales said. But therein lies a challenge for a lot of seemingly straightforward ideas that could stem the climate crisis and otherwise help people and the environment: The costs and benefits aren't always shared by the same people communities. In this particular case, installing solar panels over canals may have plenty of advantages. But why would the Department of Water Resources agree to pay a higher price for electricity when it's only going to see a fraction of the benefits itself? I discussed that question with Felicia Marcus, a former chair of the State Water Resources Control Board, who offered some guidance to the UC Merced researchers and was excited by their results. She told me their vision isn't likely to become a reality unless government agencies and entire communities can find creative ways to break down silos and work together. Maybe it's going to cost you a little more on the energy side, but you're going to get a little more on the water side. And not everything is about money, Marcus said. None of this is as simple as people think it is, she added. And yet as people professionalize, they get so buried in the details that sometimes they can't see the magic and the wonder and the common sense of the idea. Magic and wonder and common sense. We could use more of that, don't you think