Question: Read case study below to answer this question ----Do you foresee any potential problems or challenges facing AES because of the changes outlined in this

Read case study below to answer this question ----Do you foresee any potential problems or challenges facing AES because of the changes outlined in this case? How could these challenges be addressed by management?

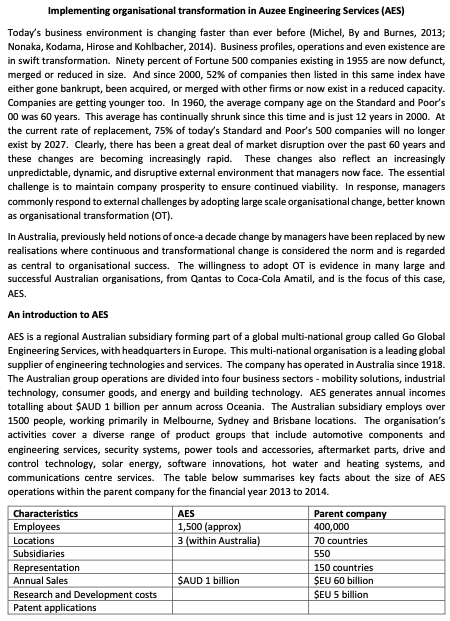

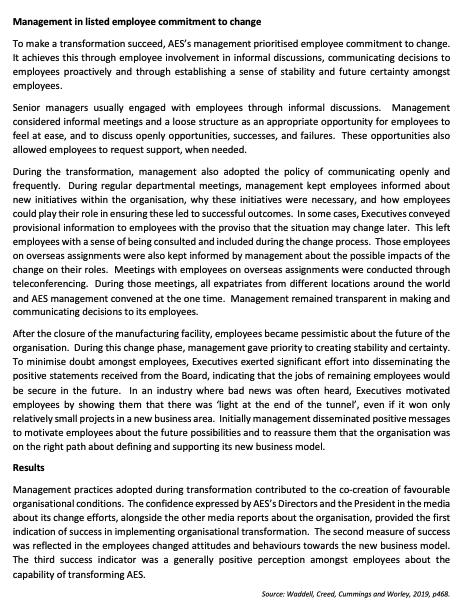

Implementing organisational transformation in Auzee Engineering Services (AES) Today's business environment is changing faster than ever before (Michel, By and Burnes, 2013; Nonaka, Kodama, Hirose and Kohlbacher, 2014). Business profiles, operations and even existence are in swift transformation. Ninety percent of Fortune 500 companies existing in 1955 are now defunct, merged or reduced in size. And since 2000,52% of companies then listed in this same index have either gone bankrupt, been acquired, or merged with other firms or now exist in a reduced capacity. Companies are getting younger too. In 1960, the average company age on the Standard and Poor's 00 was 60 years. This average has continually shrunk since this time and is just 12 years in 2000 . At the current rate of replacement, 75% of today's Standard and Poor's 500 companies will no longer exist by 2027. Clearly, there has been a great deal of market disruption over the past 60 years and these changes are becoming increasingly rapid. These changes also reflect an increasingly unpredictable, dynamic, and disruptive external environment that managers now face. The essential challenge is to maintain company prosperity to ensure continued viability. In response, managers commonly respond to external challenges by adopting large scale organisational change, better known as organisational transformation (OT). In Australia, previously held notions of once-a decade change by managers have been replaced by new realisations where continuous and transformational change is considered the norm and is regarded as central to organisational success. The willingness to adopt OT is evidence in many large and successful Australian organisations, from Qantas to Coca-Cola Amatil, and is the focus of this case, AES. An introduction to AES AES is a regional Australian subsidiary forming part of a global multi-national group called Go Global Engineering Services, with headquarters in Europe. This multi-national organisation is a leading global supplier of engineering technologies and services. The company has operated in Australia since 1918. The Australian group operations are divided into four business sectors - mobility solutions, industrial technology, consumer goods, and energy and building technology. AES generates annual incomes totalling about \$AUD 1 billion per annum across Oceania. The Australian subsidiary employs over 1500 people, working primarily in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane locations. The organisation's activities cover a diverse range of product groups that include automotive components and engineering services, security systems, power tools and accessories, aftermarket parts, drive and control technology, solar energy, software innovations, hot water and heating systems, and communications centre services. The table below summarises key facts about the size of AES operations within the parent company for the financial year 2013 to 2014. Changing winds for AES Until the financial year 2009-2010, AES was one of the largest suppliers of automotive components and technology to automotive manufacturers worldwide. From this time, the business landscape underwent rapid adjustments. Global and local trends in the automotive manufacturing industry saw falling tariff barriers and new competition from manufacturers capitalising on relatively low-cost sources of labour. These external shifts placed financial pressure on the Australian automotive component manufacturing industry that resulted in closures among several automotive component manufacturers in Australia (Australian Government Productivity Commission 2014). More generally, global forces have driven dramatic changes in the demand for motor vehicles. Organisations have responded by increasing the size and scale of production in new locations. This new competition has placed relentless pressure on traditional automotive global manufacturers, who have focused on finding new ways to reduce manufacturing costs. In fact, motor vehicle producers in Australia have not survived these increasingly highly competitive global and domestic automotive markets. Australia has a long history of mass car production. Last century, Australia produced cars that were arguably the best available in the world (Mellor 2014). Global car manufacturers, including Ford, General Motors, Mitsubishi, Nissan and Toyota located subsidiaries in Australia to produce cars for the domestic and export markets (Australian Government Productivity Commission 2014). Production realised close to 500,000 units in the 1970s. However, by 2013, the total production of Australian manufactured cars had fallen to around 200,000 units, with the Australian market becoming dominated by cars imported from Asia and Europe. At this time, Australia's share of global production was about 0.25%, and of that, approximately 40% of locally produced cars were exported (Australian Government Productivity Commission 2014). Nevertheless, the remaining car manufacturers in Australia - Toyota, General Motors, Holden and Ford - announced their intention to cease manufacturing operations in Australia. The last locally built Australian mass-produced car left the assembly line in 2017 (Davis 2017). The end of the mass car production had flow-on effects for the Australian automotive component manufacturing. This impacted AES directly. Due to the relatively high cost of Australian based manufacture/supply of automotive components, AES was no longer competitive in global markets. This was due mainly to the changing requirements and preferences of the automotive manufacturing industry globally, such as a change in geographic patterns of demand for new vehicles; global production capacity exceeding demand of new vehicles; intense competition in local global markets; changing consumer preferences; increased automotive manufacturing in developing countries; plus, cost pressures associated with doing business in Australia. These factors necessitated that AES developed a new business model to remain financially viable. A shift in AES's strategy The automotive component being manufactured at AES were primarily produced for export (up to 90% ), but due to global cost competition, it was no longer sufficiently competitive in export markets. To remain competitive in the global automotive components market, AES shifted approximately 70% of automotive components manufacturing operations to overseas locations in Asia and Europe-these locations being geographically closer to endpoint consumers. This process coinciding with a reduced local car production, was completed in 2012. AES's reduced Australian manufacturing operations had a profound impact on the company. After relocating 70% of its automotive component manufacturing operations to offshore locations, current automotive component manufacturing activities represent just 5-10\% of its \$AUD 1 billion business. As a result, approximately 400 employees were retrenched from the Melbourne facility and AES was on the verge of being shut down. However, instead of shutting down, the company chose to transform itself by changing its business model. This process involved a redirection towards finding new businesses to replace the existing business. The significant reductions in automotive component manufacturing operations in Australia necessitated diversification, through the application of technologies into new products and industries, other than automotive component manufacturing. To achieve this, the company had to actively seek business diversification and subsequent development outside of the automotive industry. The diversification meant the existing automotive-style technology and applying it to a non-passenger motor vehicle environment. For example, adapting automotive radar and camera detection systems and finding their application to rail transport. Consequently, the company had to adopt a proactive model, to explore and develop niche markets and new products. This was a counter to past practices, where AES followed a reactive model, determined by customer demand. Challenges faced by AES in implementing a new business model In 2012-2013, AES's management considered diversification into other industries products and markets. Finding alternative businesses was a significant change for AES. Traditionally employees and management had little upfront work to gain new business. Customers were usually in-house or large original equipment manufacturers that did not require matching or negotiating cut-throat competition to get the business. The strategic change of clientele now required a significant effort to explore new markets and to find new customers. This added further complexity in understanding competitors and matching their needs to the employees existing skills and technological expertise. AES had to focus on small customers rather than being an equipment supplier to large companies, such as Bunnings. Success in these new markets required employees to be more customer-oriented and flexible to customer requirements. AES's management faced huge challenges. In altering the way operated, it had no real experience exploring new business fields. To do so, it had to change its employees' understanding of the organisation's purpose - or more simply, the way they looked at their work, work practices and organisational structure. Employees understanding of organisational purpose To diversify their business, AES's employees had to change the way they interpreted and delivered the current business model, while understanding and accepting the purpose of a new business model. Almost all of AES's employees, except offers coordinators, are engineers. To comply with the new business strategy, these engineers were required to: source new business; contribute to new ideas; work on new opportunities; and overall, to become more flexible in their work practises. These activities required a fundamental shift in the way they perceive the nature of their work. Employees work practises Changes to work practises represented a significant shift for employees. Prior to the shift in their customer base, applications and systems engineering were considered distinct areas. Now engineers had to work in both domains. Additionally, engineers were to be exposed to external clients, which presented them with technical and problem-solving challenges along with the need for greater flexibility. Paralleling these changes to work practises were increased cost pressures and new processes. Engineers no longer waited for work to be allocated. Instead, they were required to conduct preliminary discussions and to work with potential clients before they could even hope to secure or start new projects. Organisation structure The new business model also meant downsizing and creating a new organisational structure. In terms of organisational structure, a shift was required from a functional structure to a customer-focused matrix structure. Subsequent employee resistance Being a longstanding engineering organisation, AES used to employ engineers with a penchant for stability and long-term horizons. In the past, these skilled employees focused exclusively on single, multi-year projects. The new business model, encompassing short-term projects, created uncertainty and anxiety amongst employees. Not surprisingly, one quarter of AES's remaining engineering employees took a redundancy or retirement package and left the organisation. Those employees who left the organisation found they did not fit in with the new business model and felt unsuited to working on new projects and technologies. Since most of the continuing employees in AES also had been working there for at least 10 years or longer, there was some dissatisfaction and implementing the new business model met with resistance from them. Leading AES through rough waters Like the employees, AES's management had little experience in implementing new business models. However, rather than hiring external consultants, it adopted an organic approach to implementing change. Knowingly or unknowingly, it dealt with the change implementation challenges by adopting the following strategies. Management was open-minded During the change implementation process, management exhibited openness to the uncertainty of its current situation and to inviting new possibilities from its employees. In relation to business diversification efforts, management was not rigid in its approach to capturing new business. Instead, it was open to the idea of new business occurring from yet unknown sources. It had also understood that a significant proportion of new business would emerge from this area. As part of its strategy of being open to the unknown, management convinced its Board, headquartered in Europe, that its new business plan should include approximately 15% of turnover from unknown sources. It did not pursue any specific business fields for new work. In addition to management's comfort with an uncertain future, the senior management team was very receptive to the new ideas generated by employees. Management's approach was to work closely with employees and to listen for new concepts. It encouraged employees to offer opinions about new opportunities and to explore these as far as possible. The engineers tended to follow a scientific approach towards testing new ideas and were more critical about time spent on these tasks. Conversely, management was very responsive to new suggestions and opportunities and to developing a vision to materialise them. To encourage employees to generate new concepts, the management team actively implemented a continuous improvement programme, known as CIP - an Internet based repository, where employees could initiate and document a new idea for improvement. Ideas thought worthy of consideration were evaluated at management team meetings. One employee was assigned the task of monitoring the overall progress of ideas generated through the continuous improvement programme. Management promoted organisational agility AES's management demonstrated its ability to rapidly respond to changes in the operational environment. To make the organisation agile, management ensured that the company became more flexible, risk taking, and only minimally compliant with headquarters strategic and operational plans. Since the new business areas were different from the conventional activities previously engaged in by AES, management emphasised the need for the organisation to become more flexible - both at individual and structural levels. Flexibility at the employee level included variable working arrangements, skill diversification, expanding job roles, and employees having freedom to drive their own careers. The flexibility in terms of organisational structure included achieving lean and therefore cost-effective structures through continuous structural adjustments. During the business diversification process, management encouraged risk taking to assist with business diversification. As subsidiary of a European parent company, AES sometimes found itself in a conflicted situation. On the one hand, the company needed to be agile for success. But, on the other hand, the multinational organisational structure policies and procedures did not support agility. Central directives from headquarters made it difficult for the Australian subsidiary to quickly act in new business fields. Management improved organisational agility through the removal of its process and procedures, or by insisting that headquarters adopt central changes to meet AES's new business plans. Management relied on employees to initiate and enact change Management valued its existing workforce, afforded them autonomy, and acknowledge and acted upon their feedback to diversify their business. Management aimed to extract benefit from existing employees through motivation and support. It shunned hiring external consultants. The new team dynamic was sufficiently strong amongst existing employees that management did not dilute their motivation by hiring employees from outside the organisation. In some cases, employees who had departed the company where approach, and offered new roles in the organisation. Management also encouraged employee autonomy. Autonomy here refers to the level of control that employees and teams had over their jobs and day-to-day work activities. Each team had its own project manager, responsible for the work. Most of the decisions concerning new projects were decided by the project manager or the project team, rather than management. Moreover, in terms of decision-making, employees were generally independent. The engineers worked autonomously, deciding when they would attend the proving grounds or undertake testing. Only decisions that impacted on a larger proportion of the organisation were made with management's input. Another form of management's reliance on employees related to feedback. The feedback here refers to employee's observations suggestions and comments about the different processes and structures introduced by management. During the change process, feedback channels created an innovation mindset among employees and encouraged employees with an entrepreneurial spirit. Management acted upon employee feedback. Where management did not consider it viable to act on an employee's suggestion, feedback was at least acknowledged. Management acknowledged feedback by informing employees in subsequent meetings that it had listened to suggestions, analysed them, and had given them consideration, and gave reasons for no action or later implementation. In some instances, where management was not able to implement a whole idea, it considered some elements of the idea to acknowledge employee feedback. Management supported knowledge sharing Management supported knowledge sharing through tapping into a deep pool of tacit knowledge within AES and its worldwide subsidiaries. The deep pool of knowledge refers to knowledge within the organisation, locally or globally, and especially within the employees. It may be knowledge gained through personal interests in technical areas that were not related to the organisation's previous activities. This encouraged the emergence of informal teams that would exchange information about how employees could work together on new and innovative technologies to win projects in different fields of business. To learn from the experience of other subsidiaries, AES often sent its employees overseas, to be cross trained by in other subsidiaries. These employees could then bring back knowledge about different areas of business that had not previously been pursued by AES. This further contributed to creating employee networks with overseas subsidiaries and these networks later provided advice to AES. In situations where employees faced a specific problem in a new business field, the problem was opened to subsidiaries worldwide. Where overseas groups with relevant experience could provide suitable advice, employees formed weekend groups where they discussed how to take skills such as sensor technology to the next level when applied to rail projects. Management was aware of this and fully supported this approach. Thus, employees shared their ideas and knowledge and further refine them before presenting them to management. Another way of tapping into the pool of tacit knowledge was to utilise the past experiences of employees, gained from previous jobs outside AES. Management respected the experience of employees gained in other organisations and let them apply this experience to assist diversification. AES's executives understood the power and importance of informal teams as it tapped into previously underutilised skill and knowledge, such as monitoring software and mobile phone applications. TO demonstrate its support for the informal groups, management permitted informal groups to add additional hours spent working on projects informally against their regular office hours. Management exercised less control An interesting and unexpected management practice was the non-directive approach adopted by Executives during the transformation. Management kept operations informal by promoting decentralisation and by not being overly critical about employees' mistakes. As the organisation moved into diverse areas, it became relatively more relaxed in terms of how and with whom employees engaged to achieve work outcomes. Consequently, the power to make decisions was increasingly deferred to the employees in the new organisational structure. Many issues, such as budgetary approval processes, became ambiguous and depended on employees own interpretation rather than relying on clarification from management. Executives did not want to define everything for employees, thus allowing employees to decide on the best options as appropriate to specific situations. Employees had reasonable relationships with each other. In circumstances where guidance was needed, they preferred having informal discussions with their peers and management, rather than going through a formalised process. Thus, the working relationships amongst employees and between employees and management became less formal, with employees taking greater responsibility for decision-making and outcomes. Generally, instead of management providing constructive criticism to employees, management encouraged employees to evaluate their own shortcomings. This approach assisted employees to understand their own positions, to reflect on their actions and their role, and to identify what they needed to do in future to learn from their mistakes. Management in listed employee commitment to change To make a transformation succeed, AES's management prioritised employee commitment to change. It achieves this through employee involvement in informal discussions, communicating decisions to employees proactively and through establishing a sense of stability and future certainty amongst employees. Senior managers usually engaged with employees through informal discussions. Management considered informal meetings and a loose structure as an appropriate opportunity for employees to feel at ease, and to discuss openly opportunities, successes, and failures. These opportunities also allowed employees to request support, when needed. During the transformation, management also adopted the policy of communicating openly and frequently. During regular departmental meetings, management kept employees informed about new initiatives within the organisation, why these initiatives were necessary, and how employees could play their role in ensuring these led to successful outcomes. In some cases, Executives conveyed provisional information to employees with the proviso that the situation may change later. This left employees with a sense of being consulted and included during the change process. Those employees on overseas assignments were also kept informed by management about the possible impacts of the change on their roles. Meetings with employees on overseas assignments were conducted through teleconferencing. During those meetings, all expatriates from different locations around the world and AES management convened at the one time. Management remained transparent in making and communicating decisions to its employees. After the closure of the manufacturing facility, employees became pessimistic about the future of the organisation. During this change phase, management gave priority to creating stability and certainty. To minimise doubt amongst employees, Executives exerted significant effort into disseminating the positive statements received from the Board, indicating that the jobs of remaining employees would be secure in the future. In an industry where bad news was often heard, Executives motivated employees by showing them that there was 'light at the end of the tunnel', even if it won only relatively small projects in a new business area. Initially management disseminated positive messages to motivate employees about the future possibilities and to reassure them that the organisation was on the right path about defining and supporting its new business model. Results Management practices adopted during transformation contributed to the co-creation of favourable organisational conditions. The confidence expressed by AES's Directors and the President in the media about its change efforts, alongside the other media reports about the organisation, provided the first indication of success in implementing organisational transformation. The second measure of success was reflected in the employees changed attitudes and behaviours towards the new business model. The third success indicator was a generally positive perception amongst employees about the capability of transforming AES. Source: Woddell, Creed, Cummings and Worley, 2019, pd6\&