Question: Read DeCSS Code on the Internet; Is it Protected Speech? By: G. Keith Roberts Do you agree that computer code and programs can merit protection

Read DeCSS Code on the Internet; Is it Protected Speech? By: G. Keith Roberts

Do you agree that computer code and programs can merit protection under First Amendment? Why?

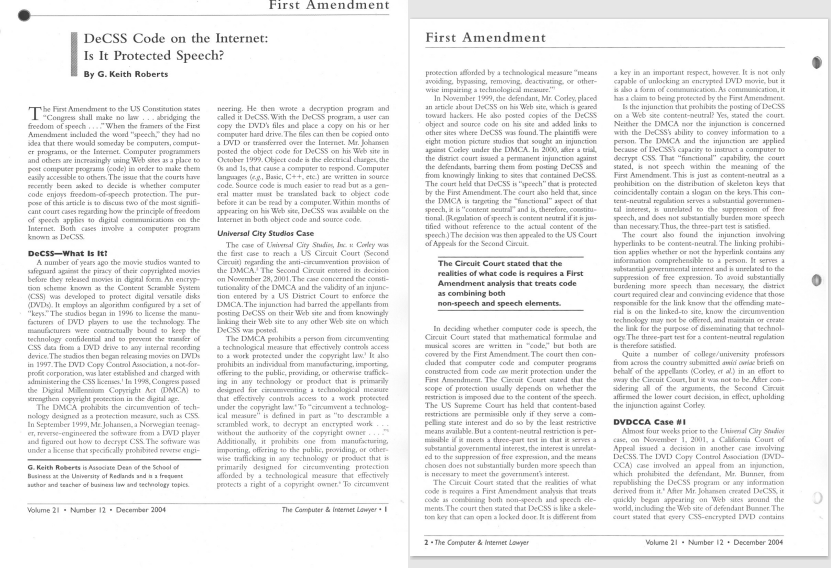

DeCSS Code on the Internet: Is It Protected Speech? By G. Keith Roberts First Amendment First Amendment he First Amendment to the US Constitution states Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech...."When the framers of the First Amendment included the word "speech," they had no idea that there would someday be computers, comput- er programs, or the Internet. Computer programmers and others are increasingly using Web sites as a place to post computer programs (code) in order to make them easily accessible to others. The issue that the courts have recently been asked to decide is whether computer code enjoys freedom-of-speech protection. The pur- pose of this article is to discuss two of the most signifi cant court cases regarding how the principle of freedom of speech applies to digital communications on the Internet. Both cases involve a computer program known as DeCSS DeCSS-What Is It? A number of years ago the movie studios wanted to safeguard against the piracy of their copyrighted movies before they released movies in digital form. An encryp tion scheme known as the Content Scramble System (CSS) was developed to protect digital versatile disks (DVD). It employs an algorithm configured by a set of "keys." The studios began in 1996 to license the manu- facturers of DVD players to use the technology. The manufacturers were contractually bound to keep the technology confidential and to prevent the transfer of CSS data from a DVD drive to any internal recording device. The studios then began releasing movies on DVDs in 1997. The DVD Copy Control Association, a not-for- profit corporation, was later established and charged with administering the CSS licenses. In 1998, Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) to strengthen copyright protection in the digital age. The DMCA prohibits the circumvention of tech- nology designed as a protection measure, such as CSS In September 1999, Mr. Johansen, a Norwegian teenag er, reverse-engineered the software from a DVD player and figured out how to decrypt CSS. The software was under a license that specifically prohibited reverse engi- G. Keith Roberts is Associate Dean of the School of Business at the University of Redlands and is a frequent author and teacher of business law and technology topics Volume 21 Number 12 December 2004 neering. He then wrote a decryption program and called it DeCSS. With the DeCSS program, a user can copy the DVD's files and place a copy on his or her computer hard drive. The files can then be copied onto a DVD or transferred over the Internet. Mr. Johansen posted the object code for DeCSS on his Web site in October 1999. Object code is the electrical charges, the Os and 1s, that cause a computer to respond. Computer languages (eg, Basic, C++, etc.) are written in source code. Source code is much easier to read but as a gen- eral matter must be translated back to object code before it can be read by a computer. Within months of appearing on his Web site, DeCSS was available on the Internet in both object code and source code. Universal City Studios Case The case of Universal City Studies, Inc. Conley was the first case to reach a US Circuit Court (Second Circuit) regarding the anti-circumvention provision of the DMCA. The Second Circuit entered its decision on November 28, 2001. The case concerned the consti- tutionality of the DMCA and the validity of an injunc- tion entered by a US District Court to enforce the DMCA. The injunction had barred the appellants from posting DeCSS on their Web site and from knowingly linking their Web site to any other Web site on which DeCSS was posted. The DMCA prohibits a person from circumventing a technological measure that effectively controls access to a work protected under the copyright law. It also prohibits an individual from manufacturing, importing, offering to the public, providing, or otherwise traffick ing in any technology or product that is primarily designed for circumventing a technological measure that effectively controls access to a work protected under the copyright law To "circumvent a technolog- ical measure is defined in part as "to descramble a scrambled work, to decrypt an encrypted work without the authority of the copyright owner... Additionally, it prohibits one from manufacturing, importing, offering to the public, providing, or other- wise trafficking in any technology or product that is primarily designed for circumventing protection afforded by a technological measure that effectively protects a right of a copyright owner. To circumvent The Computer & Intemet Lawyer I protection afforded by a technological measure "means avoiding, bypassing, removing, deactivating, or other- wise impairing a technological measure" In November 1999, the defendant, Mr. Corley, placed an article about DeCSS on his Web site, which is geared toward hackers. He also posted copies of the DeCSS object and source code on his site and added links to other sites where DeCSS was found. The plaintiffs were eight motion picture studios that sought an injunction against Corley under the DMCA. In 2000, after a trial, the district court issued a permanent injunction against the defendants, barring them from posting DeCSS and from knowingly linking to sites that contained DeCSS The court held that DeCSS is "speech" that is protected by the First Amendment. The court also held that, since the DMCA is targeting the "functional" aspect of that speech, it is "content neutral" and is, therefore, constitu tional. (Regulation of speech is content neutral if it is jus- tified without reference to the actual content of the speech.) The decision was then appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit The Circuit Court stated that the realities of what code is requires a First Amendment analysis that treats code as combining both non-speech and speech elements. In deciding whether computer code is speech, the Circuit Court stated that mathematical formulae and musical scores are written in "code" but both are covered by the First Amendment. The court then con- cluded that computer code and computer programs constructed from code cae merit protection under the First Amendment. The Circuit Court stated that the scope of protection usually depends on whether the restriction is imposed due to the content of the speech. The US Supreme Court has held that content-based restrictions are permissible only if they serve a com- pelling state interest and do so by the least restrictive means available. But a content-neutral restriction is per- missible if it meets a three-part test in that it serves a substantial governmental interest, the interest is unrelat- ed to the suppression of free expression, and the means chosen does not substantially burden more speech than is necessary to meet the government's interest. The Circuit Court stated that the realities of what code is requires a First Amendment analysis that treats code as combining both non-speech and speech ele- ments. The court then stated that DeCSS is like a skele- ton key that can open a locked door. It is different from 2. The Computer & Internet Lawyer a key in an important respect, however. It is not only capable of unlocking an encrypted DVD movie, but it is also a form of communication. As communication, it has a claim to being protected by the First Amendment. Is the injunction that prohibits the posting of DeCSS on a Web site content-neutral? Yes, stated the court. Neither the DMCA nor the injunction is concerned with the DeCSS's ability to convey information to a person. The DMCA and the injunction are applied because of DeCSS'S capacity to instruct a computer to decrypt CSS. That "functional" capability, the court stated, is not speech within the meaning of the First Amendment. This is just as content-neutral as a prohibition on the distribution of skeleton keys that coincidentally contain a slogan on the keys. This con- tent-neutral regulation serves a substantial governmen- tal interest, is unrelated to the suppression of free speech, and does not substantially burden more speech than necessary. Thus, the three-part test is satisfied. The court also found the injunction involving hyperlinks to be content-neutral. The linking prohibi- tion applies whether or not the hyperlink contains any information comprehensible to a person. It serves a substantial governmental interest and is unrelated to the suppression of free expression. To avoid substantially burdening more speech than necessary, the district court required clear and convincing evidence that those responsible for the link know that the offending mate- rial is on the linked-to site, know the circumvention technology may not be offered, and maintain or create the link for the purpose of disseminating that technol- ogy. The three-part test for a content-neutral regulation is therefore satisfied. Quite a number of college/university professors from across the country submitted awici cride briefs on behalf of the appellants (Corley, et al) in an effort to sway the Circuit Court, but it was not to be. After con- sidering all of the arguments, the Second Circuit affirmed the lower court decision, in effect, upholding the injunction against Corley. DVDCCA Case #I Almost four weeks prior to the Universal City Studios case, on November 1, 2001, a California Court of Appeal issued a decision in another case involving DeCSS. The DVD Copy Control Association (DVD- CCA) case involved an appeal from an injunction. which prohibited the defendant, Mr. Bunner, from republishing the DeCSS program or any information derived from it." After Mr. Johansen created DeCSS, it quickly began appearing on Web sites around the world, including the Web site of defendant Bunner. The court stated that every CSS-encrypted DVD contains Volume 21 Number 12 December 2004

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Yes I agree that computer code and programs can merit protection under the First Amendment The First Amendment guarantees the right to freedom of spee... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts