Question: SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT AT WAL-MART1 Ken Mark wrote this case under the supervision of Professor P. Fraser Johnson solely to provide material for class discussion.

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT AT WAL-MART1

Ken Mark wrote this case under the supervision of Professor P. Fraser Johnson solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality.

This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G 0N1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com.

Copyright 2006, Richard Ivey School of Business Foundation Version: 2017-05-30

INTRODUCTION

With US$312.4 billion in 2006 sales from operations spanning 15 countries, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (Wal- Mart) was the worlds largest retailer. Wal-Marts supply chain, a key enabler of its growth from its beginnings in rural Arkansas, was long considered by many to be a major source of competitive advantage for the company. In fact, when Wal-Mart was voted Retailer of the Decade in 1989, its distribution costs were estimated at 1.7 per cent of its cost of sales, comparing favorably with competitors such as Kmart (3.5 per cent of total sales) and Sears (five per cent of total sales).2

But by 2006, competitors were catching up. Many of Wal-Marts management techniques, which it borrowed and refined after having seen them in action at innovative retailers, were now being copied by others. By 2006, most retailers were using bar codes, shared sales data with suppliers, had in-house trucking fleets to enable self distribution, and possessed computerized point-of-sale systems that collected item-level data in real-time.

Although Wal-Mart continually searched for cost saving initiatives, in the most recent quarters, the company had been unable to meet its self-imposed target of holding inventory growth to half the level of sales growth. Wal-Marts new executive vice-president of logistics, Johnnie C. Dobbs, wondered what he could do to ensure that Wal-Marts supply chain remained a key competitive advantage for his firm.

RETAIL INDUSTRY

U.S. retail sales, excluding motor vehicles and parts dealers, reached US$2.8 trillion in 2005. Major categories in the U.S. retail industry included the following:3

1 This case has been written on the basis of published sources only. Consequently, the interpretation and perspectives presented in this case are not necessarily those of Wal-Mart or any of its employees.

2 Discount Store News, Low distribution costs buttress chains profits, 18 December 1989.

3 www.census.gov, accessed 23 August 2006.

Category 2005

(US$ billions)

General merchandise stores 525.7

Food and beverage 519.3

Food services and drinking places 396.6

Gasoline 388.3

Building materials and gardening equipment and supplies 327.0

Furniture, home furnishings, electronics and appliances 211.7

Health and personal care 208.4

Clothing and clothing accessories 201.7

Sporting goods, hobby, book, music 81.9

In the United States, retailers competed at local, regional and national levels, with some of the major chains, such as Wal-Mart and Costco, counting operations in foreign countries as well. In addition to the traditional one-store owner-operated retailer, the industry included formats such as discount stores, department stores (selling a large percentage of soft goods, i.e., clothing), variety and convenience stores, specialty stores, supermarkets, supercentres (combination discount and supermarket stores), Internet retailers and catalogue retailers. Major retailers competed for employees and store locations, as well as for customers. The 10 biggest global retailers were as follows:

Retailer 2006 Sales (US$ billions) Headquarters

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. 312.4 U.S.

Carrefour SA 88.2 France

The Home Depot, Inc. 81.5 U.S.

Metro AG 66.0 Germany

Tesco 63.7 U.K.

The Kroger Co. 60.6 U.S.

Costco 53.0 U.S.

Target Corp. 52.6 U.S.

Royal Ahold 52.2 Netherlands

Aldi Group 37.0 (est.) Germany

Source: Company reports, www.hoovers.com

The top 200 retailers accounted for approximately 30 per cent of worldwide retail sales.4 For 2005, retail sales were estimated to be US$3.7 trillion5 in the United States and CDN$572 billion in Canada.6

4 http://www.uneptie.org/pc/sustain/reports/Retail/Nov4Mtg2002/Retail_Stats.pdf, accessed 10 May 2006.

5 http://www.census.gov/mrts/www/data/pdf/annpub06.pdf, accessed 10 May 2006.

6 http://www.cardonline.ca/tools/cma_retail.cfm, accessed 10 May 2006.

BACKGROUND OF WAL-MART STORES, INC.7

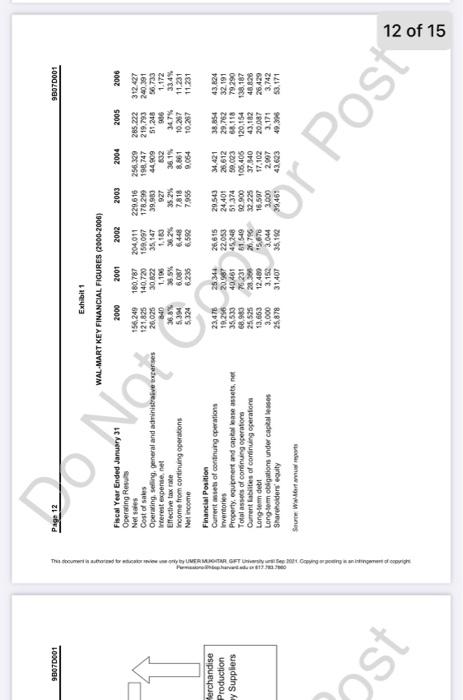

Based in Bentonville, Arkansas and founded by the legendary Sam Walton, Wal-Mart was the worlds largest retailer with more than 6,500 stores worldwide, including stores in all 50 states as well as international stores in Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico and the United Kingdom, as well as joint venture agreements in China and a stake in a leading Japanese retail chain. The company had 1.3 million employees (known as associates) in the United States and a total of 1.8 million worldwide. It was estimated that Wal-Mart served more than 138 million customers each week. Exhibit 1 presents a summary of Wal-Mart historical financial statements.

Wal-Marts strategy was to provide a broad assortment of quality merchandise and services at everyday low prices (EDLP) and was best known for its discount stores, which offered merchandise such as apparel, small appliances, housewares, electronics and hardware, but also ran combined discount and grocery stores (Wal-Mart Super Centers), membership-only warehouse stores (Sams Club), and smaller grocery stores (Neighborhood Markets). In the general merchandise area, Wal-Marts competitors included Sears and Target, with specialty retailers including Gap and The Limited. Department store competitors included Dillard, Federated and J.C. Penney. Grocery store competitors included Kroger, Albertsons and Safeway. The major membership-only warehouse competitor was Costco Wholesale.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF WAL-MARTS SUPPLY CHAIN

Before he started Wal-Mart Stores in 1962, Sam Walton owned a successful chain of stores under the Ben Franklin Stores banner, a franchisor of variety stores in the United States. Although he was under contract to purchase most of his merchandise requirements from Ben Franklin Stores, Walton was able to selectively purchase merchandise in bulk from new suppliers and then transport these goods to his stores directly. When Walton realized that a new trend, discount retailing based on driving high volumes of product through low-cost retail outlets was sweeping the nation, he decided to open up large, warehouse-style stores in order to compete. To stock his new warehouse-style stores, initially named Wal- Mart Discount City, Walton needed to step up his merchandise procurement efforts. As none of the suppliers were willing to send their trucks to his stores, which were located in rural Arkansas, self- distribution was necessary.

As Wal-Mart grew in the 1960s to 1980s, it benefited from improved road infrastructure and the inability of its competitors to react to changes in legislation, such as the removal of resale price maintenance, which had prevented retailers from discounting merchandise.

Purchasing

As his purchasing efforts increased in scale, Walton and his senior management team would make trips to buying offices in New York City, cutting out the middleman (wholesalers and distributors). Wal-Marts

U.S. buyers, located in Bentonville, worked with suppliers to ensure that the correct mix of staples and new items were ordered. Over time, many of Wal-Marts largest suppliers had offices in Bentonville, staffed by analysts and managers supporting Wal-Marts business.

7 The information contained in the background and history section is similar to that found in Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 9B06M068.

In addition, Wal-Mart started sourcing products globally, opening the first of these offices in China in the mid-1980s. Wal-Marts international purchasing offices worked directly with local factories to source Wal- Marts private label merchandise. Private label sales at Wal-Mart, first developed in the 1980s, were believed to account for 20 per cent of 2005 sales. Private label products appealed to customers since they were often priced at a significant discount to brand name merchandise; for Wal-Mart, the private label items generated higher margins than did the suppliers branded products.

Every quarter, buyers met in Bentonville to review new merchandise, exchange buying notes and tips and review a fullymerchandised prototype store, located within a warehouse. In order to gather field intelligence, buyers toured stores two or three days a week, working on the sales floors to help associates stock and sell merchandise.

Wal-Mart wielded enormous power over its suppliers. For example, observers noted that increased bargaining clout was a contributing factor in Procter & Gambles (P&G) acquisition of chief rival Gillette.8 Prior to the acquisition, sales to Wal-Mart accounted for 17 per cent of P&Gs revenues and 13 per cent of Gillettes revenues.9 On the other hand, these two suppliers combined accounted for about eight per cent of Wal-Marts sales.10 Some viewed Wal-Marts close co-operation with suppliers in a negative light:

Wal-Mart dictates that its suppliers accept payment entirely on Wal-Marts terms share information all the way back to the purchasing of raw materials. Wal-Mart controls with whom its suppliers speak, how and where they can sell their goods and even encourages them to support Wal-Mart in its political fights. Wal-Mart all but dictates to suppliers where to manufacture their products, as well as how to design those products and what materials and ingredients to use in those products.11

When negotiating with its suppliers, Wal-Mart insisted on a single invoice price and did not pay for co- operative advertising, discounting or distribution.

Globally, Wal-Mart was thought to have around 90,000 suppliers, of whom 200 such as Nestle, P&G, Unilever and Kraft were key global suppliers. With Wal-Marts expectations on sales data analysis, category management responsibilities and external research specific to their Wal-Mart business, it was not uncommon for a supplier to have several dozen employees working full-time to support the Wal-Mart business.

Distribution

Wal-Marts store openings were driven directly by its distribution strategy. Because its first distribution centre in the early 1970s was a significant investment for the firm, Walton insisted on saturating the area within a days driving distance of the distribution centres in order to gain economies of scale. Over the years, competitors copied this hub-and-spoke design of high volume distribution centres serving a cluster of stores. This distribution-led store expansion strategy persisted for the next two decades as Wal-Mart added thousands of U.S. stores, expanding across the nation from its headquarters in Arkansas.

8 http://www.newyorker.com/talk/content/?050214ta_talk_surowiecki, accessed 7 Feb 2005.

9 Larry Dignan, Procter & Gamble, Gillette Merger Could Challenge Wal-Mart RFID Adoption, Extremetech.com, accessed 31 January 2005.

10 Mark Roberti, P&G-Gillette Merger Could Benefit RFID, RFID Journal, 4 February 2005.

11 Barry C. Lynn, Breaking the chain, Harpers Magazine, July 2006, page 34.

Stores were located in low-rent, suburban areas, close to major highways. In contrast, key competitor Kmarts stores were thinly spread throughout the United States and were located in prime, urban areas. By the time the rest of the retail industry started to take notice of Wal-Mart in the 1980s, it had built up the most efficient logistics network of any retailer.

Wal-Marts 75,000-person logistics division and its information systems division included the largest private truck fleet employee base of any firm 7,800 drivers, who delivered the majority of merchandise sold at stores. Wal-Marts 114 U.S. distribution centres, located throughout the United States, were a mix of general merchandise, food and soft goods (clothing) distribution centres, processing over five billion cases a year through its entire network.

Product was picked up at the suppliers warehouse by Wal-Marts in-house trucking division and was then shipped to Wal-Marts distribution centres. Shipments were generally cross-docked, or directly transferred, from inbound to outbound trailers without extra storage. To ensure that cases moved efficiently through the distribution centres, Wal-Mart worked with suppliers to standardize case sizes and labeling. The average distance from distribution centre to stores was approximately 130 miles. Each of these distribution centres was profiled in a store-friendly way, with similar products stacked together. Merchandise purchased directly from factories in offshore locations, such as China or India, was processed at coastal distribution centres before shipment to U.S. stores.

On the way back from stores, Wal-Marts trucks generated back-haul revenue by transporting unsold merchandise on trucks that would be otherwise empty. Wal-Marts backhaul revenues its private fleet operated as a for-hire carrier when it was not busy transporting merchandise from distribution centres to stores were more than US$1 billion per year.12

Because its trucking employees were non-unionized and in-house, Wal-Mart was able to implement and improve upon standard delivery procedures, co-ordinating and deploying the entire fleet as necessary. Uniform operating standards ensured that miscommunication between traffic co-ordinators, truckers and store level employees was minimized.

Retail Strategy

Wal-Marts first stores were filled with merchandise that had been bought by Walton in bulk, as he was convinced that a new trend discounting merchandise off the suggested retail price was here to stay. In the 1960s, Wal-Mart grew rapidly as customers were attracted by its assortment of low-priced products. Over time, the company copied the merchandise assortment strategies of other retailers, mostly through observation as a result of store visits.

Unlike its competitors in the 1970s and 1980s, Wal-Mart implemented an everyday low prices (EDLP) policy, which meant that products were displayed at a steady price and not discounted on a regular basis. In a high-low discounting environment, discounts would be rotated from product to product, necessitating huge inventory stockpiles in anticipation of a discount. In an EDLP environment, demand was smoothed out to reduce the bullwhip effect. Because of its EDLP policy, Wal-Mart did not need to advertise as frequently as did its competitors and was able to channel the savings back into price reductions. To generate additional volume, Wal-Mart buyers worked with suppliers on price rollback campaigns. Price rollbacks, each lasting about 90 days, were funded by suppliers, with the goal of increasing product sales

12 http://www.dcvelocity.com/articles/july2004/inbound.cfm, accessed 19 Aug 2006.

between 200 and 500 per cent. A researcher remarked: Consumers certainly love Wal-Marts low prices, which are an average of eight per cent to 27 per cent lower than the competition.13

The company also ensured that its store-level operations were at least as efficient as its logistics operations. The stores were simply furnished and constructed using standard materials. Efforts were made to continually reduce operating costs. For example, light and temperature settings for all U.S. stores were controlled centrally from Bentonville.

As Wal-Mart distribution centres had close to real-time information on each stores in-stock levels, the merchandise could be pushed to stores automatically. In addition, store-level information systems allowed manufacturers to be notified as soon as an item was purchased. In anticipation of changes in demand for some items, associates had the authority to manually input orders or override impending deliveries. In contrast, most of Wal-Marts retail competitors did not confer merchandising responsibility to entry-level employees as merchandising templates were sent to stores through head office and were expected to be followed precisely. To ensure that employees were kept up-to-date, management shared detailed information about day/week/month store sales with all employees during daily 10-minute-long standing meetings.

The display of merchandise was suggested by a storewide template, with a unique template for each store, indicating the layout of Wal-Marts various departments. This template was created by Wal-Marts merchandising department, after analysing historical store sales and community traits. Associates were free to alter the merchandising template to fit their local store requirements. Shelf space in Wal-Marts different departments from shoes to household appliances to automotive supplies was divided up, each spot allocated to specific SKUs.

Each Wal-Mart store aimed to be the store of the community, tailoring its product mix to appeal to the distinct tastes of that community. Thus, two Wal-Mart Stores a short distance apart could potentially stock different merchandise. In contrast, most other retailers made purchasing decisions at the district or regional level.

In order to harness the knowledge of its suppliers, key category suppliers, called category captains, were introduced in the late 1980s, and they provided input on shelf space allocation. As an observer noted:

One obvious result [of using category captains] is that a producer like Colgate-Palmolive will end up working intensively with firms it formerly competed with, such as Crest manufacturer P&G, to find the mix of products that will allow Wal-Mart to earn the most it can from its shelf space. If Wal-Mart discovers that a supplier promotes its own products at the expense of Wal-Marts revenue, the retailer may name a new captain in its stead.14

Information Systems

Walton had always been interested in gathering and analysing information about his company operations. As early as 1966, when Walton had 20 stores, he attended an IBM school in upstate New York with the intent of hiring the smartest person in the class to come to Bentonville to computerize his operations.15

13 William Beaver, Battling Wal-Mart: How Communities Can Respond, Business and Society Review, New York: Summer 2005. Vol. 110, Issue 2; pg. 159.

14 Barry C. Lynn, Breaking the chain, Harpers Magazine, July 2006, page 33.

15 http://www.time.com/time/time100/builder/profile/walton2.html, accessed 23 August 2006.

Even with a growing network of stores in the 1960s and 1970s, Walton was able to personally visit and keep track of operations in each one, due to his use of a personal airplane, which he used to observe new construction development (to determine where to place stores) and to monitor customer traffic (by observing how full the parking lot was).

In the mid-1980s, Wal-Mart invested in a central database, store-level point-of-sale systems, and a satellite network. Combined with one of the retail industrys first chain-wide implementation of UPC bar codes, store-level information could now be collected instantaneously and analyzed. By combining sales data with external information such as weather forecasts, Wal-Mart was able to provide additional support to buyers, improving the accuracy of its purchasing forecasts.

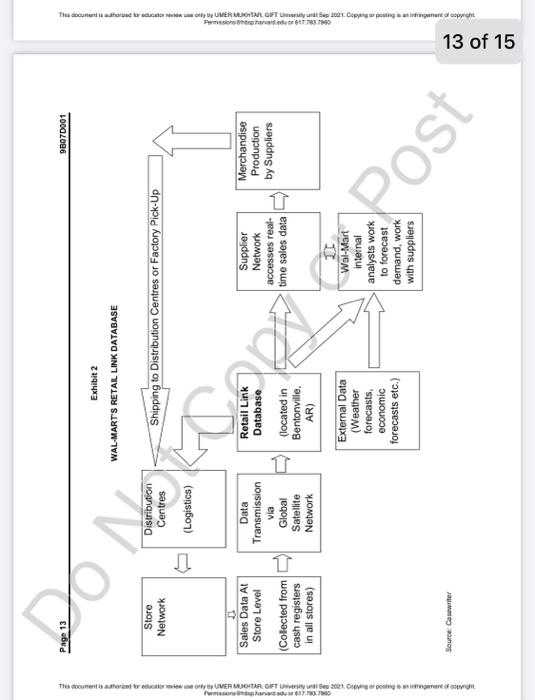

In the early 1990s, Wal-Mart developed Retail Link. At an estimated 570 terabytes which Wal-Mart claimed was larger than all the fixed pages on the Internet Retail Link was the largest civilian database in the world. For a description of how Retail Link fits in with Wal-Marts supply chain, see Exhibit 2. Retail Link contained data on every sale made at the company during a two-decade period. Wal-Mart gave its suppliers access to real-time sales data on the products they supplied, down to individual stock-keeping items at the store level.

In exchange for providing suppliers access to these data, Wal-Mart expected them to proactively monitor and replenish product on a continual basis. In 1990, Wal-Mart became one of the early adopters of collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPRF), an integrated approach to planning and forecasting by sharing critical supply chain information, such as data on promotions, inventory levels and daily sales.16 Wal-Marts vendor-managed inventory (VMI) program (also known as continuous replenishment) required suppliers to manage inventory levels at the companys distribution centres, based on agreed-upon service levels. The VMI program started with P&G diapers in the late 1980s and, by 2006, had expanded to include many suppliers and SKUs.17 In some situations, particularly grocery products, suppliers owned the inventory in Wal-Mart stores up to the point that the sale was scanned at checkout.

To support this inventory management effort, supplier analysts worked closely with Wal-Marts supply chain personnel to co-ordinate the flow of products from suppliers factories and resolved any supply chain issues, from routine issues, such as ensuring that products were ready for pickup by Wal-Marts trucks and arranging for the return of defective products, to last-minute issues, such as managing sudden spikes in demand for popular items. When Wal-Mart buyers met, on a frequent basis, with a suppliers sales teams, two important topics of review were the suppliers out-of-stock rate and inventory levels at Wal-Mart, indications of how well replenishment was being handled. Suppliers were provided with targets for out-of- stock rates and inventory levels.

In addition to managing short-term inventory and discussing product trends, Wal-Mart worked with suppliers on medium- to long-term supply chain strategy, including factory location, co-operation with downstream raw materials suppliers and production volume forecasting.

Wal-Marts satellite network, in addition to receiving and transmitting point-of-sale data, also provided senior management with the ability to broadcast video messages to the stores. Although the bulk of senior management lived and worked in Bentonville, Arkansas, frequent video broadcasts to each store in their network kept store employees informed of the latest developments in the firm.

16 Johnson, A.H., 35 Years of IT Leadership: A New Supply Chain Forged, Computerworld, September 30, 2002, pp. 38- 39.

17 Andel, T., Partnerships with Pull, Transportation and Distribution, July 1995, pp. 65-74.

In an effort to emulate Wal-Marts ability to share information with suppliers, Wal-Marts competitors relied on a system similar to Retail Link. Agentrics LLC, a software service provider, developed, in conjunction with several global retailers, a software platform called Retail Interface, which collected store level sales data that could then be shared with suppliers. Agentrics customer base included many of the worlds top retailers including Carrefour, Tesco, Metro, Costco, Kroger and Walgreens who were also investors in Agentrics.

Human Resources

By visiting each store and by encouraging associates to contribute ideas, Walton was able to uncover and disperse best practices across the company in the 1960s and 1970s. To ensure that best practices were implemented as soon as possible, Walton held regular Saturday morning meetings, which convened his top management team in Bentonville. At 7 a.m. each Saturday, the weeks business results were discussed, and merchandising and purchasing changes were implemented. Store layout resets were managed on the weekend, and the rejigged stores were ready by Monday morning. Walton and his management team often toured competitors stores, looking for new ideas to borrow.

Wal-Mart believed that centralization had numerous benefits, including lower costs and improved communications between different divisions. All of Wal-Marts divisions, from U.S. stores, International and Sams Club, to its logistics and information systems division, were located in Bentonville, a town of 28,000 people in Northwest Arkansas. Regional managers and in-country presidents were the few executives who were stationed outside of Bentonville.

Another key to Wal-Marts ability to enjoy low operating costs was the fact that it was non-union. Without cumbersome labor agreements, management could take advantage of technology to drive labor costs down and make operational changes quickly and efficiently. Being non-union, however, had its drawbacks. As its store network encroached on the territory of unionized grocers, unions, such as the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, started to become more aggressive in their anti-Wal-Mart publicity campaigns, funding so-called grassroots groups whose goals were to undermine Wal-Marts expansion. Wal-Marts size also made it a target for politicians: every stumble was magnified and played up in the press.

WAL-MART IN 2006

Wal-Mart operated approximately 3,900 stores in the United States and 2,600 stores in 13 other countries. At store level, the company stocked more than 100,000 SKUs. Two of Wal-Marts key supply chain improvement initiatives included Remix and RFID (radio frequency identification tags).

REMIX

Remix, which was started in the fall of 2005 and targeted for completion in 2007, aimed to reduce the percentage of out-of-stock merchandise at stores by redesigning its network of distribution centres. As Wal-Mart stores increased their line-up of grocery items (it was the United States largest grocer in 2005), it became apparent that, as employees sorted through truckloads of arriving merchandise to find fast-selling items, delays in restocking shelves occurred.18

18 Kris Hudson, Wal-Marts Need for Speed, The Wall Street Journal, 26 September 2005.

Moving from its original model of having distribution centres serve a cluster of stores, Wal-Mart envisioned that fast-moving merchandise, such as paper towels, toilet paper, toothpaste and seasonal items, would be shipped from dedicated high velocity food distribution centres. Food distribution centres designed to handle high-turn food items differed from general merchandise distribution centres in the following ways: they were smaller, they had temperature controls and they had less automation. In contrast, general merchandise distribution centres required automation and conveyor belts to move full pallets of goods.

Wal-Mart did not elaborate on how much savings this move was expected to generate, but it was believed to be an incremental improvement to the current system. Wal-Marts current chief information officer (CIO), Rollin Ford, stated:

We could have done nothing and been fine from a logistics standpoint but as you continue to increase your sales per square foot, youve got to do things differently to make those stores more productive.19

RFID

Mandating RFID tags on merchandise shipped by Wal-Marts top 100 suppliers was an attempt to increase the ability to track inventory, with the goal of increasing in-stock rates at store level. Privately, suppliers and observers chafed at the mandate, as it would cost them millions of dollars to implement. Publicly, Wal- Mart trumpeted RFID as a way to increase in-stock rates and reduce tracking costs. Simon Langford, Wal- Marts manager of RFID strategy, was enthusiastic about RFID:

It gives us visibility as to where the product is. Smart applications will be able to direct our associates to where the product is, so we can replenish shelves sooner. Were still working through most of the issues. Theres technology available now thats deployable in some areas. But the readers, for example, are an issue20 and were asking our (RFID technology) suppliers to accelerate their development.21

RFID tags would allow Wal-Mart to increase stock visibility as stock moved in trucks, through the distribution centres and on to the stores. Wal-Mart would be able to track promotion effectiveness within the stores while cutting out-of-stock sales losses and overstock expenses. The company placed RFID tag readers in several parts of the store: at the dock where merchandise came in, throughout the backroom, at the door from the stockroom to the sales floor, and in the box-crushing area where empty cases eventually wound up. With those readers in place, store managers would know what stock was in the backroom and what was on the sales floor.

According to researchers, about 25 per cent of out-of-stock inventory in the United States was not really out-of-stock: the items could be misplaced on the floor or mis-shelved in the backroom. U.S.-wide, about eight per cent of merchandise was out of stock at any given time, leading to lost sales for retailers. In a study performed by the University of Arkansas, Wal-Mart stores with RFID showed a net improvement of

19 http://cincom.typepad.com/simplicity/2005/09/index.html, accessed 23 Aug 2006.

20 Wal-Mart needs readers in different sizes and shapes for different locations, and they have to be designed so that antennas cannot be knocked off when a forklift backs up or lifts a pallet load. http://www.networkworld.comews/2003/0616walmart.html?page=3.

21Ibid.

16 per cent fewer out-of-stocks on the RFID-tagged products that were tested. However, RFID tags cost approximately 17 cents each.22

KEEPING INVENTORY GROWTH SLOWER THAN SALES GROWTH

In 2006, Wal-Mart continued to seek improvements to its supply chain. Although the company publicly declined to outline its targets for inventory reduction, its suppliers stated that Wal-Marts top executives spoke in January 2006 about eliminating as much as $6 billion in excess inventory.23

In the past few years, however, Wal-Marts internal goal had called for cutting its inventory growth rate to half of its sales growth rate. In its 2006 fiscal year ended January 31, the company posted a sales increase of 9.5 per cent from the previous year while its inventory grew 8.2 per cent. During the previous year, its sales increased by 11.3 per cent, while its inventory grew 11.8 per cent. The figures suggested Wal-Mart was falling short of its self-imposed target, and in April 2006, Wal-Marts chief financial officer, Tom Schoewe, stated:

If you look back at the last six or eight quarters, we have not met that objective. I think the chances of meeting that objective are greater this year than they have ever been before.24

Wal-Marts performance in international markets was also mixed. In Mexico and Canada, it was the largest retailer and enjoyed strong profits. In March 2006, it purchased a majority share in Central American Holding Company (CARHO), giving it control over 375 supermarkets and stores in Central America.

However, Wal-Mart had been faring less well in other markets. For example, in the United Kingdom, Wal- Marts ASDA unit accounted for half of Wal-Marts international sales. ASDA, the United Kingdoms second-largest supermarket chain, continued to lag behind Tesco PLC, as the latter added to its market- leading share in the country, while Sainsbury held third spot. In May 2006, a retail analyst commented that Tesco was ahead of ASDA in the lucrative and fast-growing non-food markets, such as personal care, house wares, music and video.25 A U.K.-based union publication commented:

Right now, ASDA seems to be fighting a losing battle for second place in British retailing. Trailing market leader Tesco by far, ASDA Wal-Mart has seen Sainsburys closing up through its much faster growth rate. The nervousness in Wal-Marts Bentonville headquarters has been shown by CEO Lee Scotts repeated calls for a British government intervention against Tescos strong market presence. What Mr. Scott prefers not to talk about is his own companys dominant position in global retailing.26

In May 2006, Wal-Mart pulled out of South Korea, selling its 16 stores to the countrys biggest discount chain. Wal-Mart Vice-chairman Mike Duke claimed that the firm was focusing on where it could achieve the most growth. He stated:

22 http://knowledge.wpcarey.asu.edu/index.cfm?fa=viewfeature&id=1205, 8 June 2006.

23 Kris Hudson, Wal-Mart Aims To Sharply Cut Its Inventory Costs, The Wall Street Journal, 20 April 2006. 24 Kris Hudson, Wal-Mart Aims To Sharply Cut Its Inventory Costs, The Wall Street Journal, 20 April 2006. 25 http://www.forbes.com/home/feeds/afx/2006/05/23/afx2768414.html, accessed 23 August 2006.

26 http://www.union-network.org/unisite/sectors/commerce/Multinationals/Wal-

Mart_Asda_warehouse_workers_vote_on_strike.htm, accessed 23 August 2006.

It became increasingly clear that in South Koreas current environment, it would be difficult for us to reach the scale we desired.27

In August 2006, Wal-Mart exited the German market with losses of about $1 billion after eight years of failing to turn around its two acquisitions, purchased in 1997 and 1998. Wal-Marts performance in its core domestic market was also suffering. In mid-August 2006, Wal-Mart posted its first profit decline in a decade.28

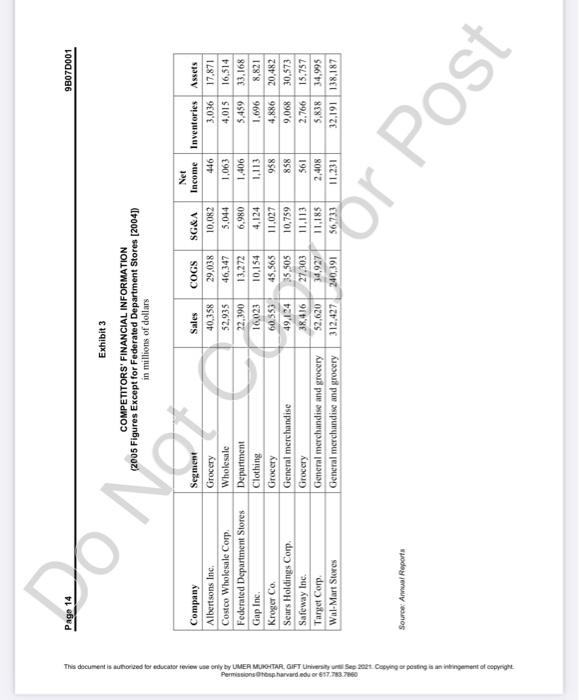

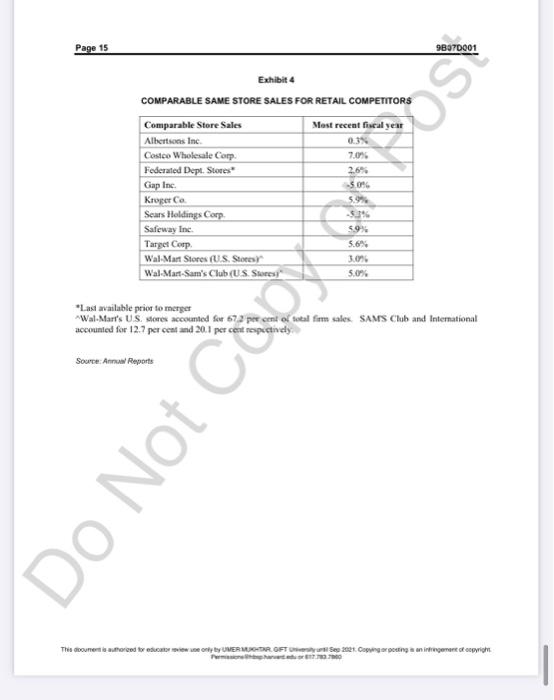

Competitors such as Target Stores and Costco seemed to be catching up, growing comparable store sales faster than Wal-Mart. For competitors financials, see Exhibit 3; for comparable same store sales, see Exhibit 4.

(kindly read this case study and solve it and answer the following questions (this is 25 marks midterm kindly answer accoeding to it ) and give me proper answers

if its not possible to read it kindly search on google"half centuray of supply chain management At Wal-Mart "

questions are

1. Write a brief summary of the case study.

2. Describe Wal-Mart's supply chain and how it integrates with the other elements in its strategy?

3. Why has Wal-Mart not been as successful in Europe as it has in North America?

4. How are Wal-Mart's problems with its supply chain related to its global expansion?

(i also uploaded the remaiming pictures kindly also read it and answer me properly)

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock