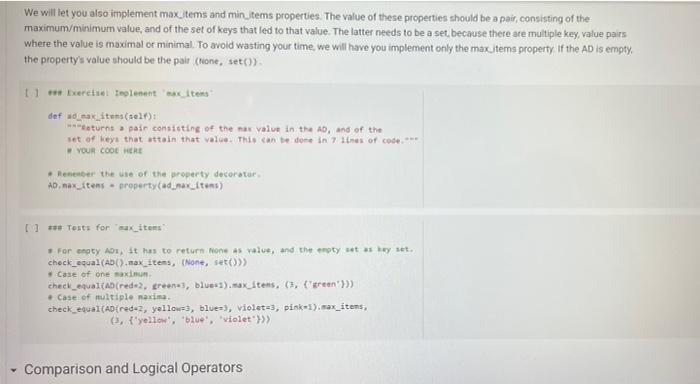

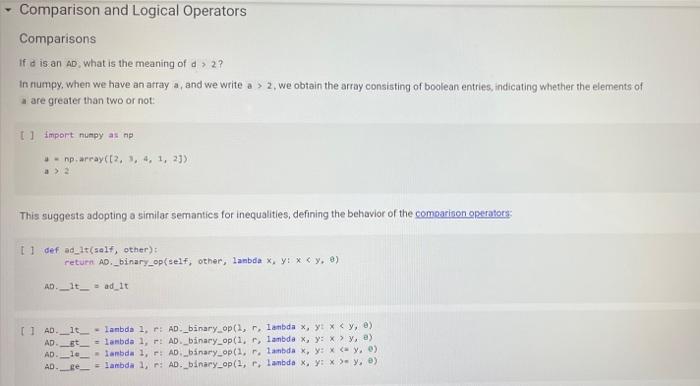

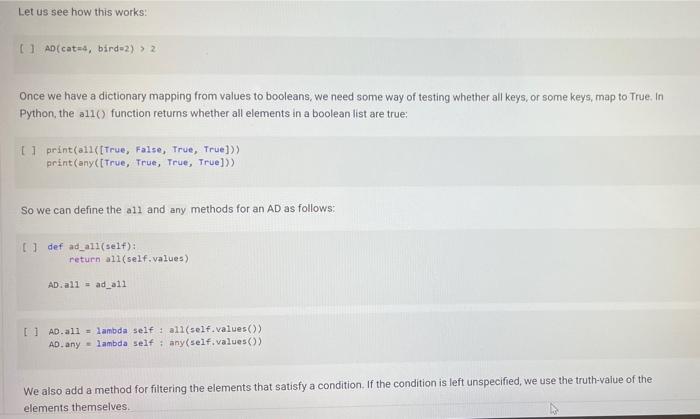

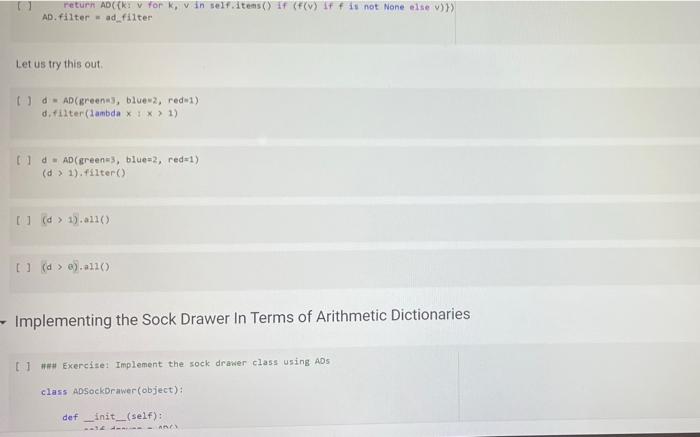

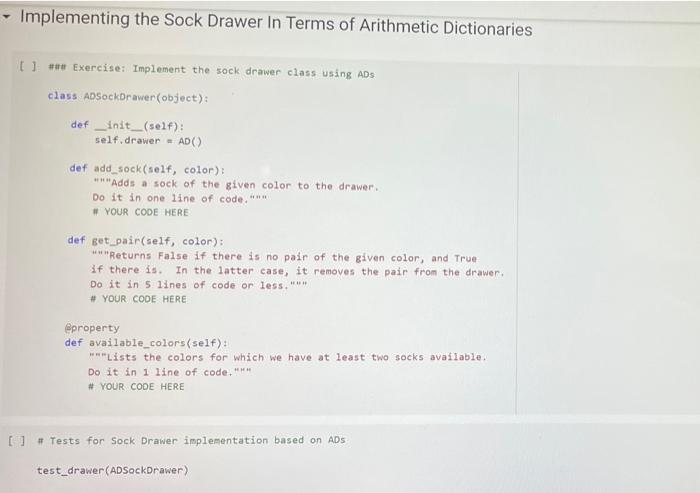

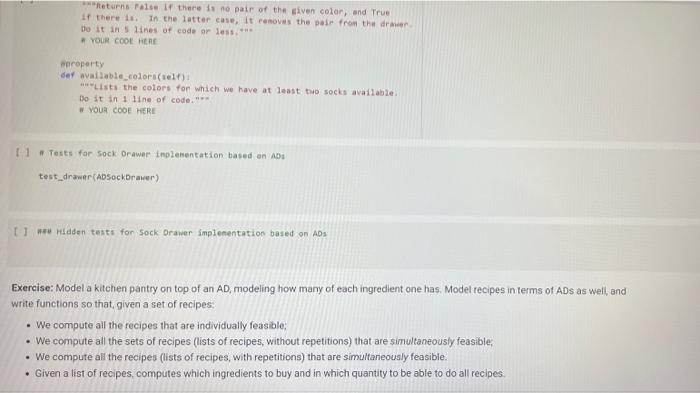

Question: use python do the work in every space where it says #YOUR CODE HERE A Sock Drawer Let us model a sock drawer. How does

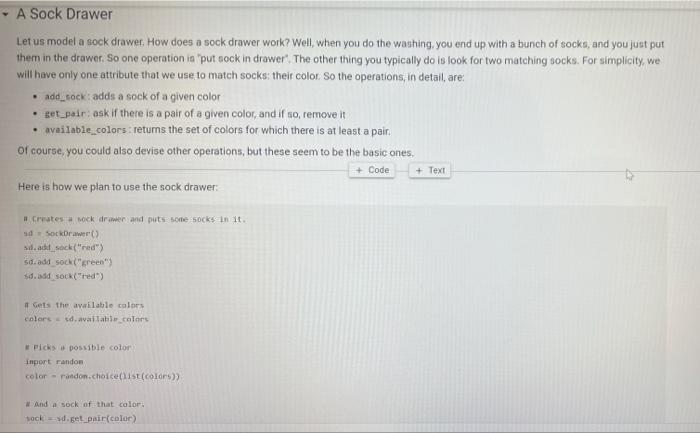

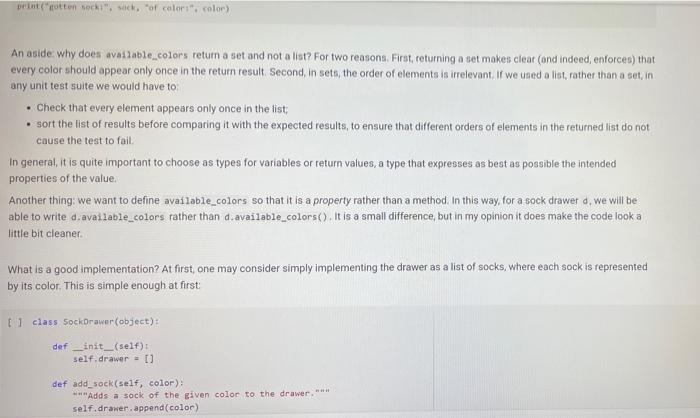

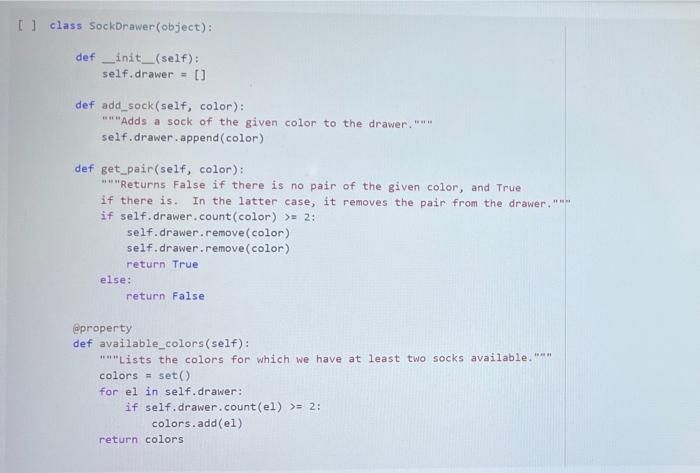

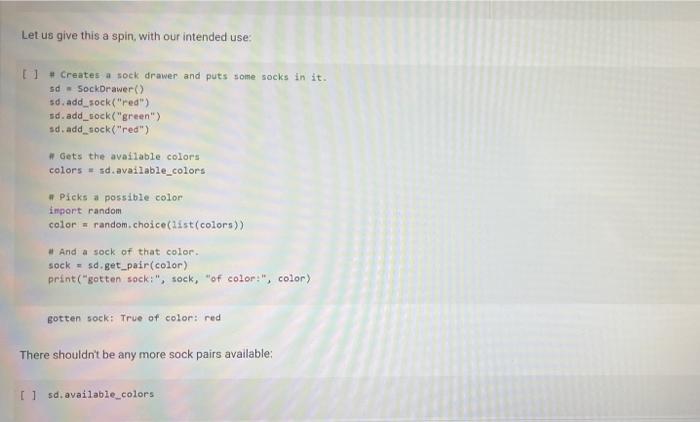

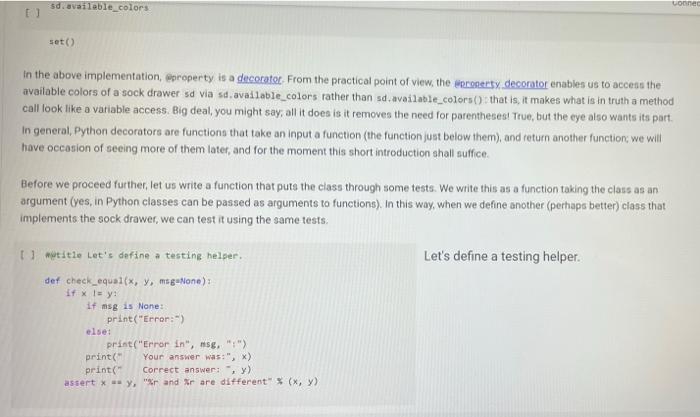

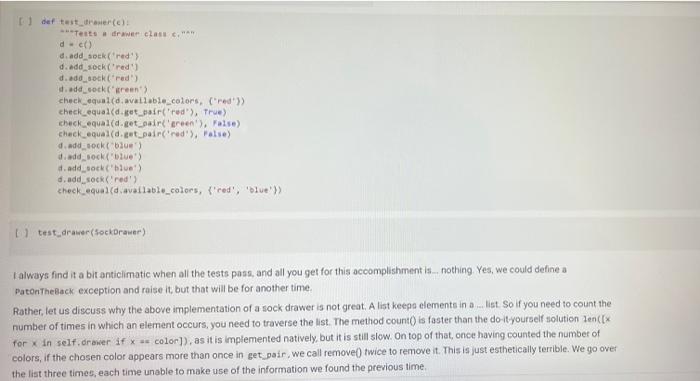

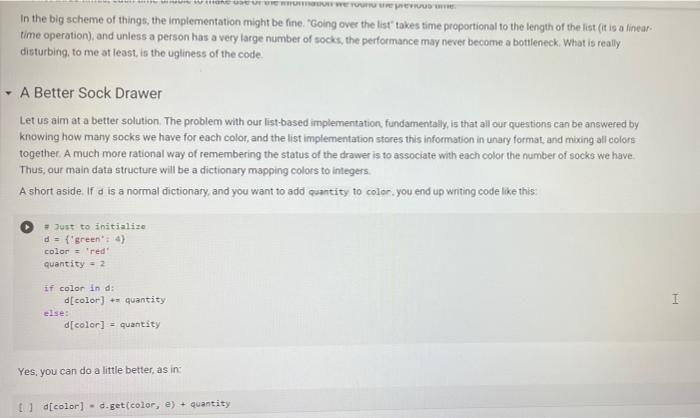

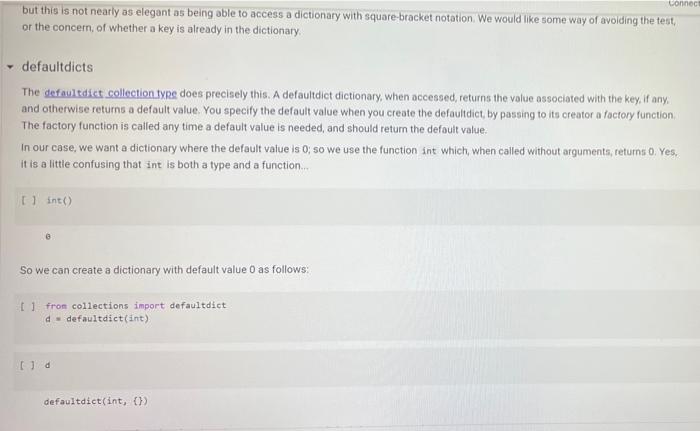

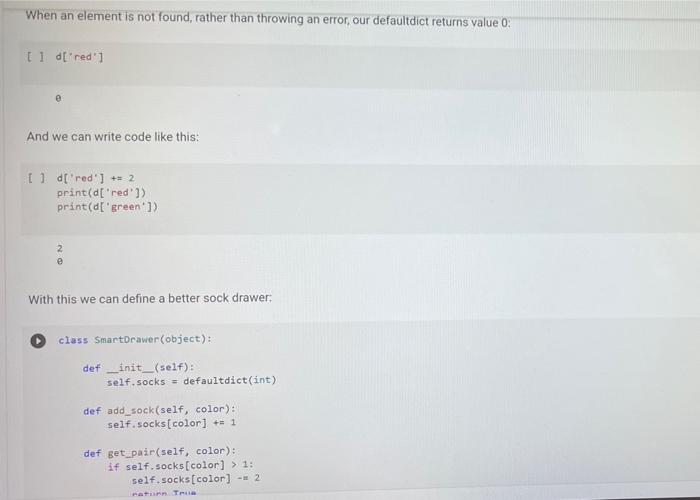

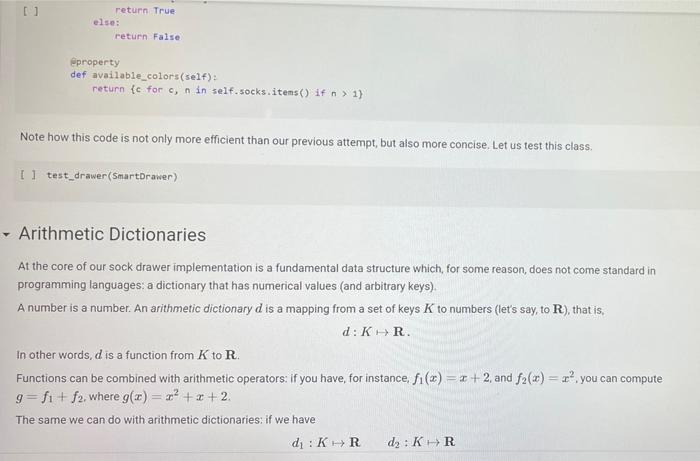

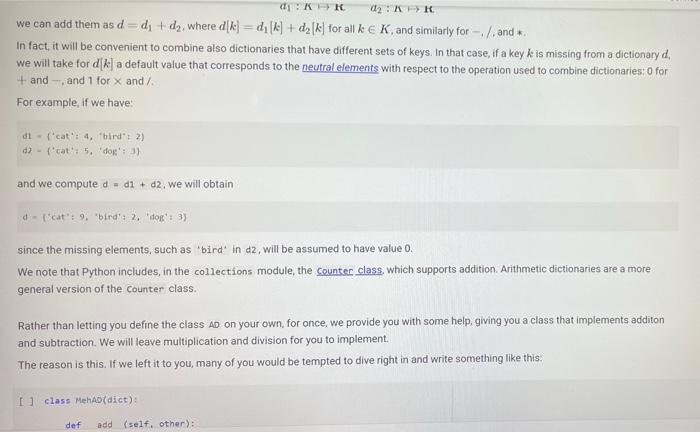

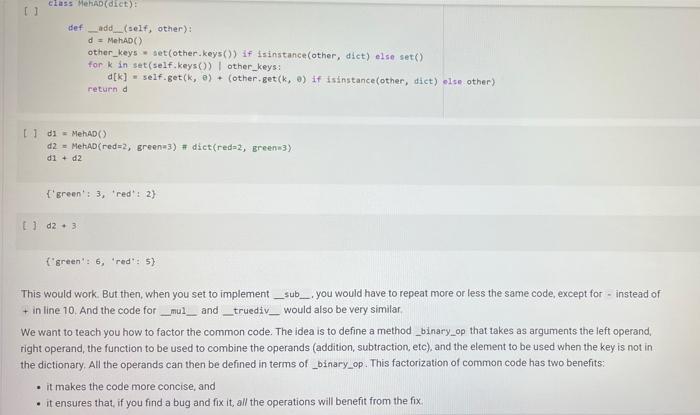

A Sock Drawer Let us model a sock drawer. How does a sock drawer work? Well, when you do the washing you end up with a bunch of socks, and you just put them in the drawer. So one operation in "put sock in drawer. The other thing you typically do is look for two matching socks. For simplicity, we will have only one attribute that we use to match socks: their color. So the operations, in detail, are add_cock: adds a sock of a given color get_pair: ask if there is a pair of a given color, and if so, remove it available_colors: returns the set of colors for which there is at least a pair. Of course, you could also devise other operations, but these seem to be the basic ones, + Code + Text Here is how we plan to use the sock drawer Creates a cock drawer and puts some socks in it SockDrawer) Sad sock("red") Sd. add sock"green") d.add sock"red) Gets the available colors colors sd, available.colors picks possible color inport random color - randon.choicelist (colors) And a sock of that calor. ock = d.get_pair(color) proton sockisk, of colori, color) An aside: why does valable colors return a set and not a list? For two reasons. First, returning a set makes clear (ond indeed, enforce) that every color should appear only once in the return result. Second, in sets, the order of elements is irrelevant. If we used a list, rather than a set in any unit test suite we would have to . Check that every element appears only once in the list sort the list of results before comparing it with the expected results, to ensure that different orders of elements in the returned list do not cause the test to fait In general, it is quite important to choose as types for variables or return values, a type that expresses as best as possible the intended properties of the value Another thing we want to define available_colors so that it is a property rather than a method. In this way, for a sock drawer d, we will be able to write d available_colors rather than d.available_colors(). It is a small difference, but in my opinion it does make the code look a little bit cleaner. What is a good implementation? At first, one may consider simply implementing the drawer as a list of socks, where each sock is represented by its color. This is simple enough at first Il class SockDrawer(object) def __init__(self): self.drawer = [] def add_sock (self, color): Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer.** self.drawer.append(color) [] class SockDrawer (object): def _init__(self): self.drawer = [] def add_sock(self, color): Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer." self.drawer.append(color) def get_pair(self, color): **Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is. In the latter case, it removes the pair from the drawer, if self.drawer.count(color) >= 2: self.drawer.remove(color) self.drawer.remove(color) return True else: return false @property def available_colors(self): """Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available. *** colors = set() for el in self.drawer: if self.drawer.count(el) >= 2: colors.add(el) return colors Let us give this a spin with our intended use: # Creates a sock drawer and puts some socks in it. sd SockDrawer() sd.add_sock("red") sd.add_cock("green") sd.add_sock("red") # Gets the available colors colors - sd.available_colors # Picks a possible color import random color = random.choice(list(colors) # And a sock of that color. sock = sd.get_pair(color) print("gotten sock;", sock, "of color:", color) gotten sock: True of color: red There shouldn't be any more sock pairs available: Il sd.available_colors Lonnec sd available_colors set() In the above implementation, property is a decoratet From the practical point of view, the property decorator enables us to access the available colors of a sock drawer sd via sd, available_colors rather than sd available_colors() that is, it makes what is in truth a method call look like a variable access. Big deal, you might say, all it does is it removes the need for parentheses! True, but the eye also wants its part In general, Python decorators are functions that take an input a function (the function just below them), and return another function, we will have occasion of seeing more of them later, and for the moment this short introduction shall suffice. Before we proceed further, let us write a function that puts the class through some tests. We write this as a function taking the class as an argument (yes, in Python classes can be passed as arguments to functions). In this way, when we define another (perhaps better) class that implements the sock drawer, we can test it using the same tests. Let's define a testing helper. 11 title Let's define a testing helper. def check_equal(x, y, msg=None): If x=y: if msg is None: print("Error:) else: print("Error in", ng, ":") print(" Your answer was:", X) print Correct answer", y) assert X usy, "Crand Xr are different" (x, y) def testere Tests #drawerclass d) d. add_sockred> d. add sockred) d. add_sockred) dadd_cokreen) check_equalcd.wallable_colors, 'red'>> check_equal(d.get_arred), True) check_equal(d.get_pairgreen). False) check_equal(d.getpaired, False) d. addock (blue) daddock(ov d.addock 'blue') d. add sockred) check_equaldavailable_colors, {'red', 'blue'>> Il test drawer (Sockorawer) I always find it a bit anticilmatic when all the tests pass, and all you get for this accomplishment is... nothing Yes, we could define a PatonTheBack exception and raise it, but that will be for another time, Rather, let us discuss why the above implementation of a sock drawer is not great. A list keeps elements in a ... Ist So if you need to count the number of times in which an element occurs, you need to traverse the list. The method count() is faster than the do it yourself solution denix for x in self.drawer if x - color]), as it is implemented natively, but it is still slow. On top of that, once having counted the number of colors, if the chosen color appears more than once in get pair we call remove) twice to remove it. This is just esthetically terrible. We go over the list three times, each time unable to make use of the information we found the previous time, we ROWEROWE In the big scheme of things, the implementation might be fine. "Going over the list takes time proportional to the length of the list (it is a linear time operation), and unless a person has a very large number of socks, the performance may never become a bottleneck. What is really disturbing to me at least, is the ugliness of the code. A Better Sock Drawer Let us alm at a better solution. The problem with our list-based implementation fundamentally, is that all our questions can be answered by knowing how many socks we have for each color, and the list implementation stores this information in unary format, and mixing all colors together. A much more rational way of remembering the status of the drawer is to associate with each color the number of socks we have. Thus, our main data structure will be a dictionary mapping colors to integers. A short aside If d is a normal dictionary, and you want to add quantity to color you end up writing code like this #Just to initialize d = 1 green=6) color="red Quantity = 2 1 if color in di d[color) + quantity else: d[color] = quantity Yes, you can do a little better, as in []d[color] - d.get(color, e) + quantity connec but this is not nearly as elegant as being able to access a dictionary with square-bracket notation. We would like some way of avoiding the test, or the concern of whether a key is already in the dictionary defaultdicts The defaultdict collection tyre does precisely this. A defaultdiet dictionary, when accessed, returns the value associated with the key if any. and otherwise returns a default value. You specify the default value when you create the defaultdict by passing to its creator a factory function, The factory function is called any time a default value is needed, and should return the default value. In our case, we want a dictionary where the default value is 0; so we use the function in which, when called without arguments, returns 0. Yes, it is a little confusing that int is both a type and a function. [into) So we can create a dictionary with default value as follows: [ 1 fron collections import defaultdict d-defaultdict(int) 10 defaultdict(int, (>) When an element is not found, rather than throwing an error, our defaultdict returns value 0 tl d['red' e And we can write code like this: 11 d['red'] ++ 2 print(a['red']) print(a['green']) 2 e With this we can define a better sock drawer class SmartDrawer(object): def __init_(self): self.socks = defaultdict(int) def add_sock(self, color): self socks [color] += 1 def get_pair(self, color): if self.socks [color] > 1: self.socks [color] -- 2 raturn TRI [] return True else: return false property def available_colors(self): return {c for c, n in self socks.items() if n > 1) Note how this code is not only more efficient than our previous attempt, but also more concise. Let us test this class. [ 1 test_drawer (SmartDrawer) - Arithmetic Dictionaries At the core of our sock drawer implementation is a fundamental data structure which, for some reason does not come standard in programming languages: a dictionary that has numerical values and arbitrary keys). A number is a number. An arithmetic dictionary d is a mapping from a set of keys K to numbers (let's say, to R), that is, d: KR In other words, d is a function from K to R. Functions can be combined with arithmetic operators: if you have, for instance, f1(c)==+2, and fa() = r, you can compute g=fi + f2, where g(x) = x + x +2. The same we can do with arithmetic dictionaries: if we have di : KR dy: KR dKEK 2:> we can add them as d=d; + dy, where d[k] = d.lk] + d2[k] for all k e K, and similarly for -- /. and In fact, it will be convenient to combine also dictionaries that have different sets of keys. In that case, if a keyk is missing from a dictionaryd, we will take for d[k) a default value that corresponds to the neutral elements with respect to the operation used to combine dictionaries:0 for + and -, and 1 for x and/ For example, if we have: of'cat: 4. 'bird2) ) - ('cat' 5, dog': 3) and we compute d = 1 + d2. we will obtain 4 - 'cat': . bird': 2. do: 3) since the missing elements, such as 'bird in d2, will be assumed to have value o We note that Python includes, in the collections module, the counter class, which supports addition, Arithmetic dictionaries are a more general version of the counter class. Rather than letting you define the class AD on your own for once, we provide you with some help, giving you a class that implements additon and subtraction. We will leave multiplication and division for you to implement, The reason is this. If we left it to you, many of you would be tempted to dive right in and write something like this: [] class MehAD(dict): def add (self. other): class MehAD (diet) def add(self, other): d = MehAD) other_keys - set (other.keys() if isinstance(other, dict) else set() for k in set(self.keys) other_keys: a[k) - self.get(k, e) (other.get(ko) if isinstance(other, dict) else other) return d [ 1 di MehAD) d2 - MehAD (red, green-3) # dict(redp2, green 3) d1 + d2 t'green': 3, 'red': 2) 1 02 ('green': 6, 'redt: 5) This would work. But then, when you set to implement _sub_. you would have to repeat more or less the same code, except for - instead of + in line 10. And the code for _mul_ and _truediv_ would also be very similar We want to teach you how to factor the common code. The idea is to define a method _binary_op that takes as arguments the left operand, right operand, the function to be used to combine the operands (addition, subtraction, etc), and the element to be used when the key is not in the dictionary, All the operands can then be defined in terms of _binary_op. This factorization of common code has two benefits: . it makes the code more concise and it ensures that if you find a bug and fix it all the operations will benefit from the fix, Code factorization means gathering together the common code, eliminating repetition; just as factoring ab + ac into a (b + c) removes the repetition of a. It turns out that the deep reason why code factorization is important is not conciseness: rather, it is the fact that once a bug is discovered in the factorized code, all uses of the code will benefit from it. The code is as follows: class AD (dict) def __add_(self, other) return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, yx + y ) def __sub_(self, other): return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, y: * - ), o) staticmethod def binary op(left, right, op, neutral): = AD() 1_keys = set(left. keys() if isinstance(left, dict) else set() r_keys set(right.keys()) if isinstance(right, dict) else set) for kin 1_keys Ir_keys: # If the right (or left) element is a dictionary (or an AD), # we get the elements from the dictionary; else we use the right W or left value itself. This implements sort of dictionary #broadcasting 1_val-left.get(k, neutral) if isinstance(left, dict) else left ruval - right.get(k, neutral) if is instance(right, dict) else right [K] - op(1_val, r_val) return In the implementation above, we have factored together what would have been the common part of the implementation of + and - in the In the implementation above, we have factored together what would have been the common part of the implementation of + and - in the method _binary_op. The _binary op method is a static method. It does not refer to a specific object. In this way, we can decide separately what to provide to it as the left and right hand sides; this will be useful later, as we shall see. To call it, we have to refer to it via D._binary op rather than self._binary_op, as would be the case for a normal (object) method. Furthermore, in the _binary op method, we do not have access to self, since self refers to a specific object, while the method is generic, defined for the class. The binary op method combines values from its left and right operands using operator op, and the default neutral if a value is not found. The two operands left and right are interpreted as dictionaries if they are a subclass of dict, and are interpreted as constants otherwise We have defined our class AD as a subclass of the dictionary class diet. This enables us to apply to an AD all the methods that are defined for a dictionary, which is really quite handy 1) di . AD) d1[red) - 2 print(1) d2 = AD('blue': 4, 'green': 5}) print(02) {'red': 2) ('blue': 4, 'green' 5} In the code above, note how we can write d1['red']: our ability to access ADs via the square-bracket notation is due to the fact that ADs, like dictionaries, implement the __eetiten method. Note also that AD inherits from dict even the initializer methods, so that we can pass to our dictionary another dictionary, and obtain an AD that contains a copy of that dictionary We can see that addition and subtraction also work: We can see that addition and subtraction also work: [ 1 print (AD(red-2, green-3) + AD(red-1, blue=4>> print(AD (red-2, green=3) - AD(red=1, blue-)) 'green': 3, 'red': 3, 'blue': 4) ('green': 3, 'red': 1, 'blue': -4) We let multiplication and division to you to implement U *** Exercise: Implement multiplication and division def ad_mul(self, other) # YOUR CODE HERE AD . _ mul__ * ad_mul Define below division, similarly. # YOUR CODE HERE And finally, define below INTEGER division. # YOUR CODE HERE * Tests for multiplication # Note that the elements that are missing in the other dictionary # are assumed to be 1. d = AD(H2, b=3) - AD(64, C5) check oual/dAnasha1253 Conne are assumed to be 1. d AD(32, 3) AD(-4, C-5) check_equal(d, AD(2-2, 6-12, c=5)) [ www Tests for division d = AD(-8, b26) / AD(-2, 04) check_equal(d, AD(2-4, 6-5, C+0.25)) *** Tests for integer division d = AD(HB, bab) // AD(H2, 4, C4) check_equal(d, AD(4, b=1, cue)) We will let you also implement max_items and min_items properties. The value of these properties should be a pair, consisting of the maximum/minimum value, and of the set of keys that led to that value. The latter needs to be a set, because there are multiple key, value pairs where the value is maximal or minimal. To avoid wasting your time, we will have you implement only the max.Items property. If the AD is empty the property's value should be the pair (Nane, seto). [ ] *** Exercise: Implement "max_items! def ad_max_itens(self): **Returns a pair consisting of the max value in the AD, and of the set of keys that attain that value. This can be done in 7 lines of code. We will let you also implement max_tems and min. Jtems properties. The value of these properties should be a pair, consisting of the maximum/minimum value, and of the set of keys that led to that value. The latter needs to be a set because there are multiple key value pairs where the value is maximal or minimal. To avoid wasting your time, we will have you implement only the max Items property If the AD is empty. the property's value should be the pair (None, set()) *** Exercise implement itens def ad_max_itens(self): eturns pair consisting of the mar value in the AD, and of the set of keys that attain that value. This can be done in 7 ltnes of code *** 7 - YOUR COOL HERE Rennbar the use of the property decoratie AD, max_iten property(ad_ar_iters) [] Tests for sax_items For enoty A1, it has to return one as value, and the empty set as key set. check_equal(AD().max_items, (None, set() >> Case of one saximum check_equal (Acrede2, green, bluet).max Itens, (3, green'>>> Case of multiple maxima check_equal(AD (red-2, yellow, blues), violet 3, piskai).ax_items () {'yellow', 'blue', 'violet >>> Comparison and Logical Operators Comparison and Logical Operators Comparisons ifa is an Ad what is the meaning of a > 2? In numpy, when we have an array a, and we write a > 2, we obtain the array consisting of boolean entries, indicating whether the elements of a are greater than two or not: [ ] Import numpy as no np array(t?. , 4, 1, 23) 3 > 2 This suggests adopting a similar semantics for inequalities, defining the behavior of the comparison operators [ 1 def adult(salt, other) return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, y: xy. ) AD. It_ad_it 11 AD 1t_ - lambda , r: AD._binary op, r, lambda x, yxy, e) AD.Et = lambda 1, P: AD._binary op(1. r, lambda x, y: x > y, e) AD - lambda 1, r AD._binary op(1. , lambda x, y: x 2 Once we have a dictionary mapping from values to booleans, we need some way of testing whether all keys, or some keys, map to True. In Python, the allo function returns whether all elements in a boolean list are true: 1 print(aik ([True, False, True, True]>> print(any ([True, True, True, True])) So we can define the all and any methods for an AD as follows: [ ] def ad_all(self): return all(self.values) AD all = ad all [] AD.all = lambda seif : all(self.values()) AD.any - lambda self : any(self.values()) We also add a method for filtering the elements that satisfy a condition. If the condition is left unspecified, we use the truth-value of the elements themselves. return ADCERT V for k, van self.items() IF (FC) IT fit not None else >>> AD. filter - ad filter Let us try this out U d AD (green, blue, rede1) o filter (lambda x1 x > 1) Id AD (green, blue-2, red=1) (d) 1). filter() U (d > 1).(110) I d > 0).allo > - Implementing the Sock Drawer In Terms of Arithmetic Dictionaries U www Exercite: Implement the sock drawer class using ADS class ADSockDrawer(object): def init__(self): --- - Implementing the Sock Drawer In Terms of Arithmetic Dictionaries [ ] *** Exercise: Implement the sock drawer class using ADS class ApSockDrawer(object): def __init_(self) self.drawer = ADC) def add_sock(self, color) Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer. Do it in one line of code # YOUR CODE HERE def get pair(self, color): Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is. In the latter case, it removes the pair from the drawer Do it in 5 lines of code or less." # YOUR CODE HERE @property def available_colors(self): Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available. Do it in 1 line of code. # YOUR CODE HERE [] # Tests for Sock Drawer implementation based on ADS test_drawer (ADSockDrawer) Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is in the latter case, it remove the pain from the dar Do it in lines of code or less # YOUR COOL HERE eroperty def available_colors(self) Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available Do it in 1 line of code." # YOUR COOE HERE 1 1 Tests for Sock Drawer inlenentation based on test_drawer (Asockbrewer) Hidden tests for Sock Drawer implementation based on AD Exercise: Model a kitchen pantry on top of an AD, modeling how many of each ingredient one has. Model recipes in terms of ADs as well, and write functions so that given a set of recipes: . We compute all the recipes that are individually feasible; . We compute all the sets of recipes (lists of recipes, without repetitions) that are simultaneously feasible, . We compute all the recipes (lists of recipes, with repetitions) that are simultaneously feasible. . Given a list of recipes, computes which ingredients to buy and in which quantity to be able to do all recipes A Sock Drawer Let us model a sock drawer. How does a sock drawer work? Well, when you do the washing you end up with a bunch of socks, and you just put them in the drawer. So one operation in "put sock in drawer. The other thing you typically do is look for two matching socks. For simplicity, we will have only one attribute that we use to match socks: their color. So the operations, in detail, are add_cock: adds a sock of a given color get_pair: ask if there is a pair of a given color, and if so, remove it available_colors: returns the set of colors for which there is at least a pair. Of course, you could also devise other operations, but these seem to be the basic ones, + Code + Text Here is how we plan to use the sock drawer Creates a cock drawer and puts some socks in it SockDrawer) Sad sock("red") Sd. add sock"green") d.add sock"red) Gets the available colors colors sd, available.colors picks possible color inport random color - randon.choicelist (colors) And a sock of that calor. ock = d.get_pair(color) proton sockisk, of colori, color) An aside: why does valable colors return a set and not a list? For two reasons. First, returning a set makes clear (ond indeed, enforce) that every color should appear only once in the return result. Second, in sets, the order of elements is irrelevant. If we used a list, rather than a set in any unit test suite we would have to . Check that every element appears only once in the list sort the list of results before comparing it with the expected results, to ensure that different orders of elements in the returned list do not cause the test to fait In general, it is quite important to choose as types for variables or return values, a type that expresses as best as possible the intended properties of the value Another thing we want to define available_colors so that it is a property rather than a method. In this way, for a sock drawer d, we will be able to write d available_colors rather than d.available_colors(). It is a small difference, but in my opinion it does make the code look a little bit cleaner. What is a good implementation? At first, one may consider simply implementing the drawer as a list of socks, where each sock is represented by its color. This is simple enough at first Il class SockDrawer(object) def __init__(self): self.drawer = [] def add_sock (self, color): Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer.** self.drawer.append(color) [] class SockDrawer (object): def _init__(self): self.drawer = [] def add_sock(self, color): Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer." self.drawer.append(color) def get_pair(self, color): **Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is. In the latter case, it removes the pair from the drawer, if self.drawer.count(color) >= 2: self.drawer.remove(color) self.drawer.remove(color) return True else: return false @property def available_colors(self): """Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available. *** colors = set() for el in self.drawer: if self.drawer.count(el) >= 2: colors.add(el) return colors Let us give this a spin with our intended use: # Creates a sock drawer and puts some socks in it. sd SockDrawer() sd.add_sock("red") sd.add_cock("green") sd.add_sock("red") # Gets the available colors colors - sd.available_colors # Picks a possible color import random color = random.choice(list(colors) # And a sock of that color. sock = sd.get_pair(color) print("gotten sock;", sock, "of color:", color) gotten sock: True of color: red There shouldn't be any more sock pairs available: Il sd.available_colors Lonnec sd available_colors set() In the above implementation, property is a decoratet From the practical point of view, the property decorator enables us to access the available colors of a sock drawer sd via sd, available_colors rather than sd available_colors() that is, it makes what is in truth a method call look like a variable access. Big deal, you might say, all it does is it removes the need for parentheses! True, but the eye also wants its part In general, Python decorators are functions that take an input a function (the function just below them), and return another function, we will have occasion of seeing more of them later, and for the moment this short introduction shall suffice. Before we proceed further, let us write a function that puts the class through some tests. We write this as a function taking the class as an argument (yes, in Python classes can be passed as arguments to functions). In this way, when we define another (perhaps better) class that implements the sock drawer, we can test it using the same tests. Let's define a testing helper. 11 title Let's define a testing helper. def check_equal(x, y, msg=None): If x=y: if msg is None: print("Error:) else: print("Error in", ng, ":") print(" Your answer was:", X) print Correct answer", y) assert X usy, "Crand Xr are different" (x, y) def testere Tests #drawerclass d) d. add_sockred> d. add sockred) d. add_sockred) dadd_cokreen) check_equalcd.wallable_colors, 'red'>> check_equal(d.get_arred), True) check_equal(d.get_pairgreen). False) check_equal(d.getpaired, False) d. addock (blue) daddock(ov d.addock 'blue') d. add sockred) check_equaldavailable_colors, {'red', 'blue'>> Il test drawer (Sockorawer) I always find it a bit anticilmatic when all the tests pass, and all you get for this accomplishment is... nothing Yes, we could define a PatonTheBack exception and raise it, but that will be for another time, Rather, let us discuss why the above implementation of a sock drawer is not great. A list keeps elements in a ... Ist So if you need to count the number of times in which an element occurs, you need to traverse the list. The method count() is faster than the do it yourself solution denix for x in self.drawer if x - color]), as it is implemented natively, but it is still slow. On top of that, once having counted the number of colors, if the chosen color appears more than once in get pair we call remove) twice to remove it. This is just esthetically terrible. We go over the list three times, each time unable to make use of the information we found the previous time, we ROWEROWE In the big scheme of things, the implementation might be fine. "Going over the list takes time proportional to the length of the list (it is a linear time operation), and unless a person has a very large number of socks, the performance may never become a bottleneck. What is really disturbing to me at least, is the ugliness of the code. A Better Sock Drawer Let us alm at a better solution. The problem with our list-based implementation fundamentally, is that all our questions can be answered by knowing how many socks we have for each color, and the list implementation stores this information in unary format, and mixing all colors together. A much more rational way of remembering the status of the drawer is to associate with each color the number of socks we have. Thus, our main data structure will be a dictionary mapping colors to integers. A short aside If d is a normal dictionary, and you want to add quantity to color you end up writing code like this #Just to initialize d = 1 green=6) color="red Quantity = 2 1 if color in di d[color) + quantity else: d[color] = quantity Yes, you can do a little better, as in []d[color] - d.get(color, e) + quantity connec but this is not nearly as elegant as being able to access a dictionary with square-bracket notation. We would like some way of avoiding the test, or the concern of whether a key is already in the dictionary defaultdicts The defaultdict collection tyre does precisely this. A defaultdiet dictionary, when accessed, returns the value associated with the key if any. and otherwise returns a default value. You specify the default value when you create the defaultdict by passing to its creator a factory function, The factory function is called any time a default value is needed, and should return the default value. In our case, we want a dictionary where the default value is 0; so we use the function in which, when called without arguments, returns 0. Yes, it is a little confusing that int is both a type and a function. [into) So we can create a dictionary with default value as follows: [ 1 fron collections import defaultdict d-defaultdict(int) 10 defaultdict(int, (>) When an element is not found, rather than throwing an error, our defaultdict returns value 0 tl d['red' e And we can write code like this: 11 d['red'] ++ 2 print(a['red']) print(a['green']) 2 e With this we can define a better sock drawer class SmartDrawer(object): def __init_(self): self.socks = defaultdict(int) def add_sock(self, color): self socks [color] += 1 def get_pair(self, color): if self.socks [color] > 1: self.socks [color] -- 2 raturn TRI [] return True else: return false property def available_colors(self): return {c for c, n in self socks.items() if n > 1) Note how this code is not only more efficient than our previous attempt, but also more concise. Let us test this class. [ 1 test_drawer (SmartDrawer) - Arithmetic Dictionaries At the core of our sock drawer implementation is a fundamental data structure which, for some reason does not come standard in programming languages: a dictionary that has numerical values and arbitrary keys). A number is a number. An arithmetic dictionary d is a mapping from a set of keys K to numbers (let's say, to R), that is, d: KR In other words, d is a function from K to R. Functions can be combined with arithmetic operators: if you have, for instance, f1(c)==+2, and fa() = r, you can compute g=fi + f2, where g(x) = x + x +2. The same we can do with arithmetic dictionaries: if we have di : KR dy: KR dKEK 2:> we can add them as d=d; + dy, where d[k] = d.lk] + d2[k] for all k e K, and similarly for -- /. and In fact, it will be convenient to combine also dictionaries that have different sets of keys. In that case, if a keyk is missing from a dictionaryd, we will take for d[k) a default value that corresponds to the neutral elements with respect to the operation used to combine dictionaries:0 for + and -, and 1 for x and/ For example, if we have: of'cat: 4. 'bird2) ) - ('cat' 5, dog': 3) and we compute d = 1 + d2. we will obtain 4 - 'cat': . bird': 2. do: 3) since the missing elements, such as 'bird in d2, will be assumed to have value o We note that Python includes, in the collections module, the counter class, which supports addition, Arithmetic dictionaries are a more general version of the counter class. Rather than letting you define the class AD on your own for once, we provide you with some help, giving you a class that implements additon and subtraction. We will leave multiplication and division for you to implement, The reason is this. If we left it to you, many of you would be tempted to dive right in and write something like this: [] class MehAD(dict): def add (self. other): class MehAD (diet) def add(self, other): d = MehAD) other_keys - set (other.keys() if isinstance(other, dict) else set() for k in set(self.keys) other_keys: a[k) - self.get(k, e) (other.get(ko) if isinstance(other, dict) else other) return d [ 1 di MehAD) d2 - MehAD (red, green-3) # dict(redp2, green 3) d1 + d2 t'green': 3, 'red': 2) 1 02 ('green': 6, 'redt: 5) This would work. But then, when you set to implement _sub_. you would have to repeat more or less the same code, except for - instead of + in line 10. And the code for _mul_ and _truediv_ would also be very similar We want to teach you how to factor the common code. The idea is to define a method _binary_op that takes as arguments the left operand, right operand, the function to be used to combine the operands (addition, subtraction, etc), and the element to be used when the key is not in the dictionary, All the operands can then be defined in terms of _binary_op. This factorization of common code has two benefits: . it makes the code more concise and it ensures that if you find a bug and fix it all the operations will benefit from the fix, Code factorization means gathering together the common code, eliminating repetition; just as factoring ab + ac into a (b + c) removes the repetition of a. It turns out that the deep reason why code factorization is important is not conciseness: rather, it is the fact that once a bug is discovered in the factorized code, all uses of the code will benefit from it. The code is as follows: class AD (dict) def __add_(self, other) return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, yx + y ) def __sub_(self, other): return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, y: * - ), o) staticmethod def binary op(left, right, op, neutral): = AD() 1_keys = set(left. keys() if isinstance(left, dict) else set() r_keys set(right.keys()) if isinstance(right, dict) else set) for kin 1_keys Ir_keys: # If the right (or left) element is a dictionary (or an AD), # we get the elements from the dictionary; else we use the right W or left value itself. This implements sort of dictionary #broadcasting 1_val-left.get(k, neutral) if isinstance(left, dict) else left ruval - right.get(k, neutral) if is instance(right, dict) else right [K] - op(1_val, r_val) return In the implementation above, we have factored together what would have been the common part of the implementation of + and - in the In the implementation above, we have factored together what would have been the common part of the implementation of + and - in the method _binary_op. The _binary op method is a static method. It does not refer to a specific object. In this way, we can decide separately what to provide to it as the left and right hand sides; this will be useful later, as we shall see. To call it, we have to refer to it via D._binary op rather than self._binary_op, as would be the case for a normal (object) method. Furthermore, in the _binary op method, we do not have access to self, since self refers to a specific object, while the method is generic, defined for the class. The binary op method combines values from its left and right operands using operator op, and the default neutral if a value is not found. The two operands left and right are interpreted as dictionaries if they are a subclass of dict, and are interpreted as constants otherwise We have defined our class AD as a subclass of the dictionary class diet. This enables us to apply to an AD all the methods that are defined for a dictionary, which is really quite handy 1) di . AD) d1[red) - 2 print(1) d2 = AD('blue': 4, 'green': 5}) print(02) {'red': 2) ('blue': 4, 'green' 5} In the code above, note how we can write d1['red']: our ability to access ADs via the square-bracket notation is due to the fact that ADs, like dictionaries, implement the __eetiten method. Note also that AD inherits from dict even the initializer methods, so that we can pass to our dictionary another dictionary, and obtain an AD that contains a copy of that dictionary We can see that addition and subtraction also work: We can see that addition and subtraction also work: [ 1 print (AD(red-2, green-3) + AD(red-1, blue=4>> print(AD (red-2, green=3) - AD(red=1, blue-)) 'green': 3, 'red': 3, 'blue': 4) ('green': 3, 'red': 1, 'blue': -4) We let multiplication and division to you to implement U *** Exercise: Implement multiplication and division def ad_mul(self, other) # YOUR CODE HERE AD . _ mul__ * ad_mul Define below division, similarly. # YOUR CODE HERE And finally, define below INTEGER division. # YOUR CODE HERE * Tests for multiplication # Note that the elements that are missing in the other dictionary # are assumed to be 1. d = AD(H2, b=3) - AD(64, C5) check oual/dAnasha1253 Conne are assumed to be 1. d AD(32, 3) AD(-4, C-5) check_equal(d, AD(2-2, 6-12, c=5)) [ www Tests for division d = AD(-8, b26) / AD(-2, 04) check_equal(d, AD(2-4, 6-5, C+0.25)) *** Tests for integer division d = AD(HB, bab) // AD(H2, 4, C4) check_equal(d, AD(4, b=1, cue)) We will let you also implement max_items and min_items properties. The value of these properties should be a pair, consisting of the maximum/minimum value, and of the set of keys that led to that value. The latter needs to be a set, because there are multiple key, value pairs where the value is maximal or minimal. To avoid wasting your time, we will have you implement only the max.Items property. If the AD is empty the property's value should be the pair (Nane, seto). [ ] *** Exercise: Implement "max_items! def ad_max_itens(self): **Returns a pair consisting of the max value in the AD, and of the set of keys that attain that value. This can be done in 7 lines of code. We will let you also implement max_tems and min. Jtems properties. The value of these properties should be a pair, consisting of the maximum/minimum value, and of the set of keys that led to that value. The latter needs to be a set because there are multiple key value pairs where the value is maximal or minimal. To avoid wasting your time, we will have you implement only the max Items property If the AD is empty. the property's value should be the pair (None, set()) *** Exercise implement itens def ad_max_itens(self): eturns pair consisting of the mar value in the AD, and of the set of keys that attain that value. This can be done in 7 ltnes of code *** 7 - YOUR COOL HERE Rennbar the use of the property decoratie AD, max_iten property(ad_ar_iters) [] Tests for sax_items For enoty A1, it has to return one as value, and the empty set as key set. check_equal(AD().max_items, (None, set() >> Case of one saximum check_equal (Acrede2, green, bluet).max Itens, (3, green'>>> Case of multiple maxima check_equal(AD (red-2, yellow, blues), violet 3, piskai).ax_items () {'yellow', 'blue', 'violet >>> Comparison and Logical Operators Comparison and Logical Operators Comparisons ifa is an Ad what is the meaning of a > 2? In numpy, when we have an array a, and we write a > 2, we obtain the array consisting of boolean entries, indicating whether the elements of a are greater than two or not: [ ] Import numpy as no np array(t?. , 4, 1, 23) 3 > 2 This suggests adopting a similar semantics for inequalities, defining the behavior of the comparison operators [ 1 def adult(salt, other) return AD._binary op(self, other, lambda x, y: xy. ) AD. It_ad_it 11 AD 1t_ - lambda , r: AD._binary op, r, lambda x, yxy, e) AD.Et = lambda 1, P: AD._binary op(1. r, lambda x, y: x > y, e) AD - lambda 1, r AD._binary op(1. , lambda x, y: x 2 Once we have a dictionary mapping from values to booleans, we need some way of testing whether all keys, or some keys, map to True. In Python, the allo function returns whether all elements in a boolean list are true: 1 print(aik ([True, False, True, True]>> print(any ([True, True, True, True])) So we can define the all and any methods for an AD as follows: [ ] def ad_all(self): return all(self.values) AD all = ad all [] AD.all = lambda seif : all(self.values()) AD.any - lambda self : any(self.values()) We also add a method for filtering the elements that satisfy a condition. If the condition is left unspecified, we use the truth-value of the elements themselves. return ADCERT V for k, van self.items() IF (FC) IT fit not None else >>> AD. filter - ad filter Let us try this out U d AD (green, blue, rede1) o filter (lambda x1 x > 1) Id AD (green, blue-2, red=1) (d) 1). filter() U (d > 1).(110) I d > 0).allo > - Implementing the Sock Drawer In Terms of Arithmetic Dictionaries U www Exercite: Implement the sock drawer class using ADS class ADSockDrawer(object): def init__(self): --- - Implementing the Sock Drawer In Terms of Arithmetic Dictionaries [ ] *** Exercise: Implement the sock drawer class using ADS class ApSockDrawer(object): def __init_(self) self.drawer = ADC) def add_sock(self, color) Adds a sock of the given color to the drawer. Do it in one line of code # YOUR CODE HERE def get pair(self, color): Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is. In the latter case, it removes the pair from the drawer Do it in 5 lines of code or less." # YOUR CODE HERE @property def available_colors(self): Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available. Do it in 1 line of code. # YOUR CODE HERE [] # Tests for Sock Drawer implementation based on ADS test_drawer (ADSockDrawer) Returns False if there is no pair of the given color, and True if there is in the latter case, it remove the pain from the dar Do it in lines of code or less # YOUR COOL HERE eroperty def available_colors(self) Lists the colors for which we have at least two socks available Do it in 1 line of code." # YOUR COOE HERE 1 1 Tests for Sock Drawer inlenentation based on test_drawer (Asockbrewer) Hidden tests for Sock Drawer implementation based on AD Exercise: Model a kitchen pantry on top of an AD, modeling how many of each ingredient one has. Model recipes in terms of ADs as well, and write functions so that given a set of recipes: . We compute all the recipes that are individually feasible; . We compute all the sets of recipes (lists of recipes, without repetitions) that are simultaneously feasible, . We compute all the recipes (lists of recipes, with repetitions) that are simultaneously feasible. . Given a list of recipes, computes which ingredients to buy and in which quantity to be able to do all recipes

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts