Question: Using the information below create multiple paragraphs about Egyptian culture. 7.3. Funerary culture and society Tombs provide the largest body of archaeological evidence for the

Using the information below create multiple paragraphs about Egyptian culture.

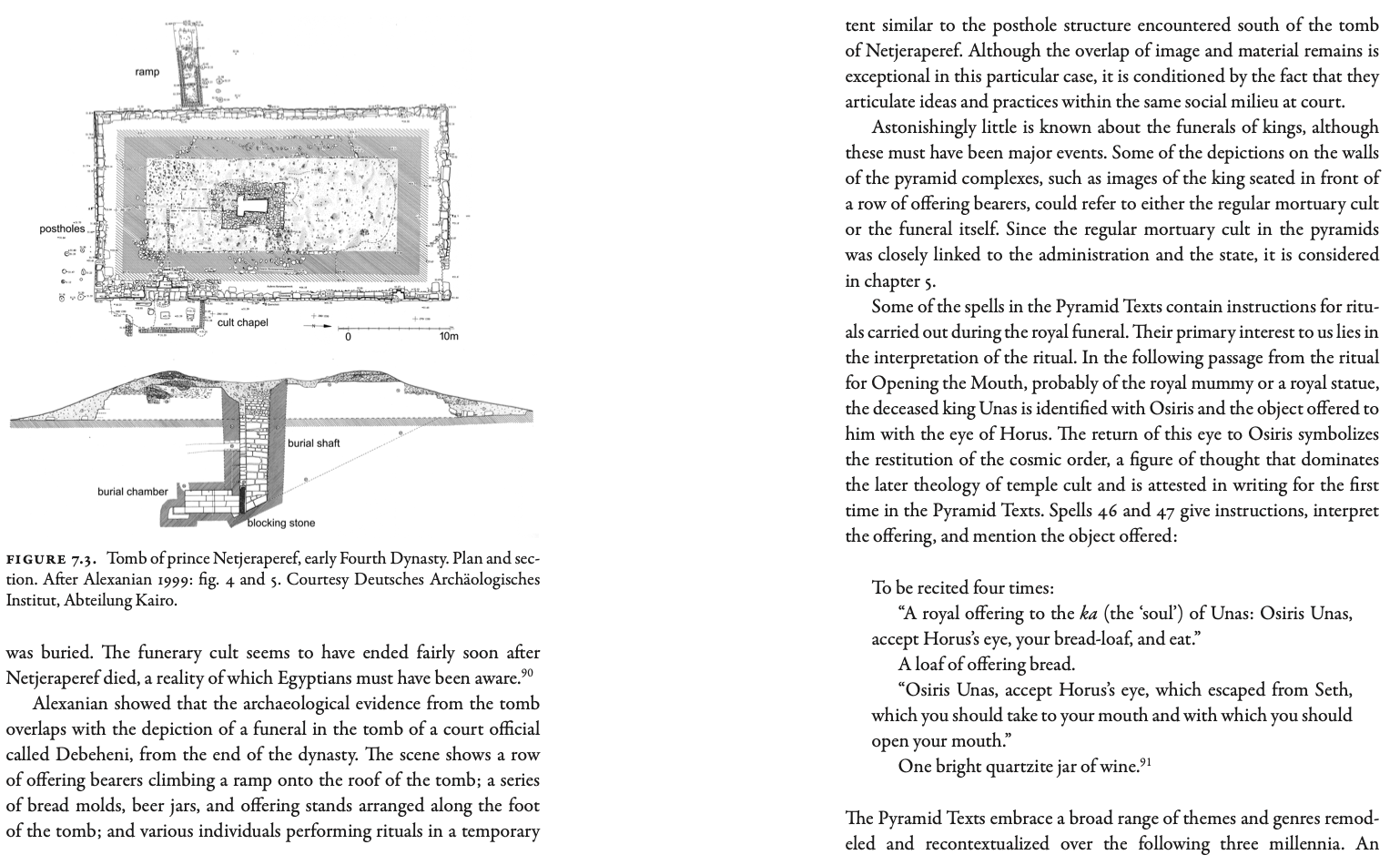

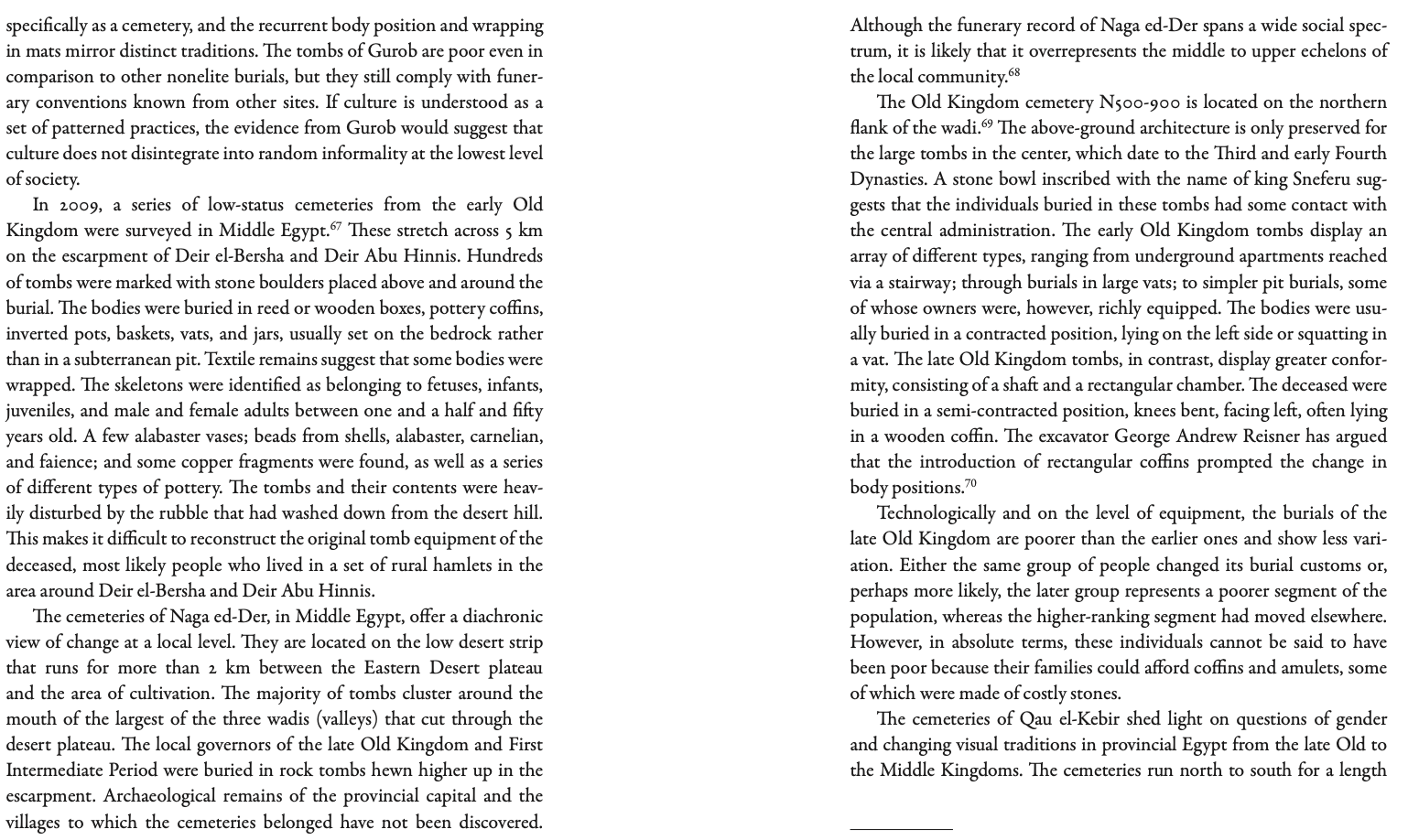

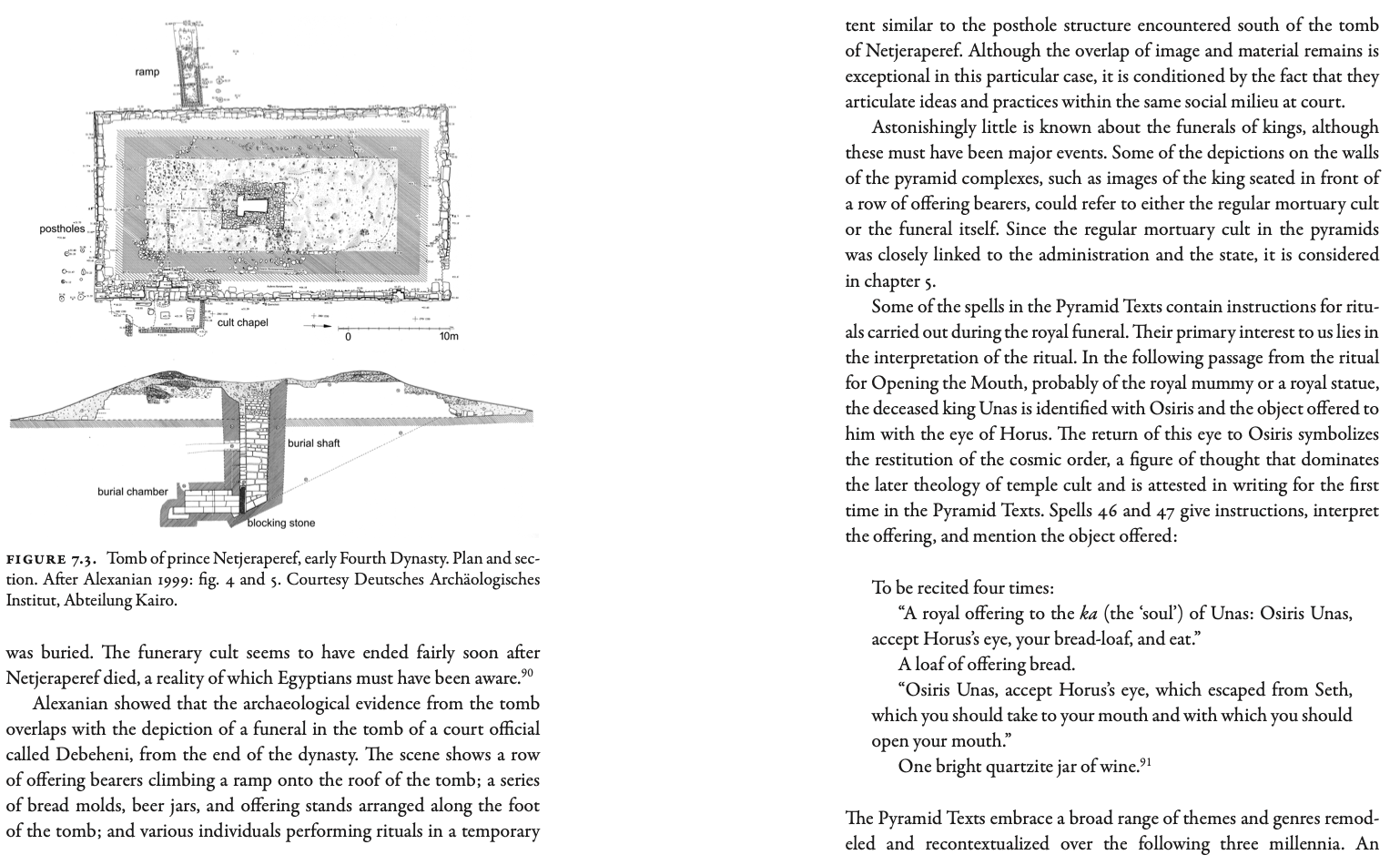

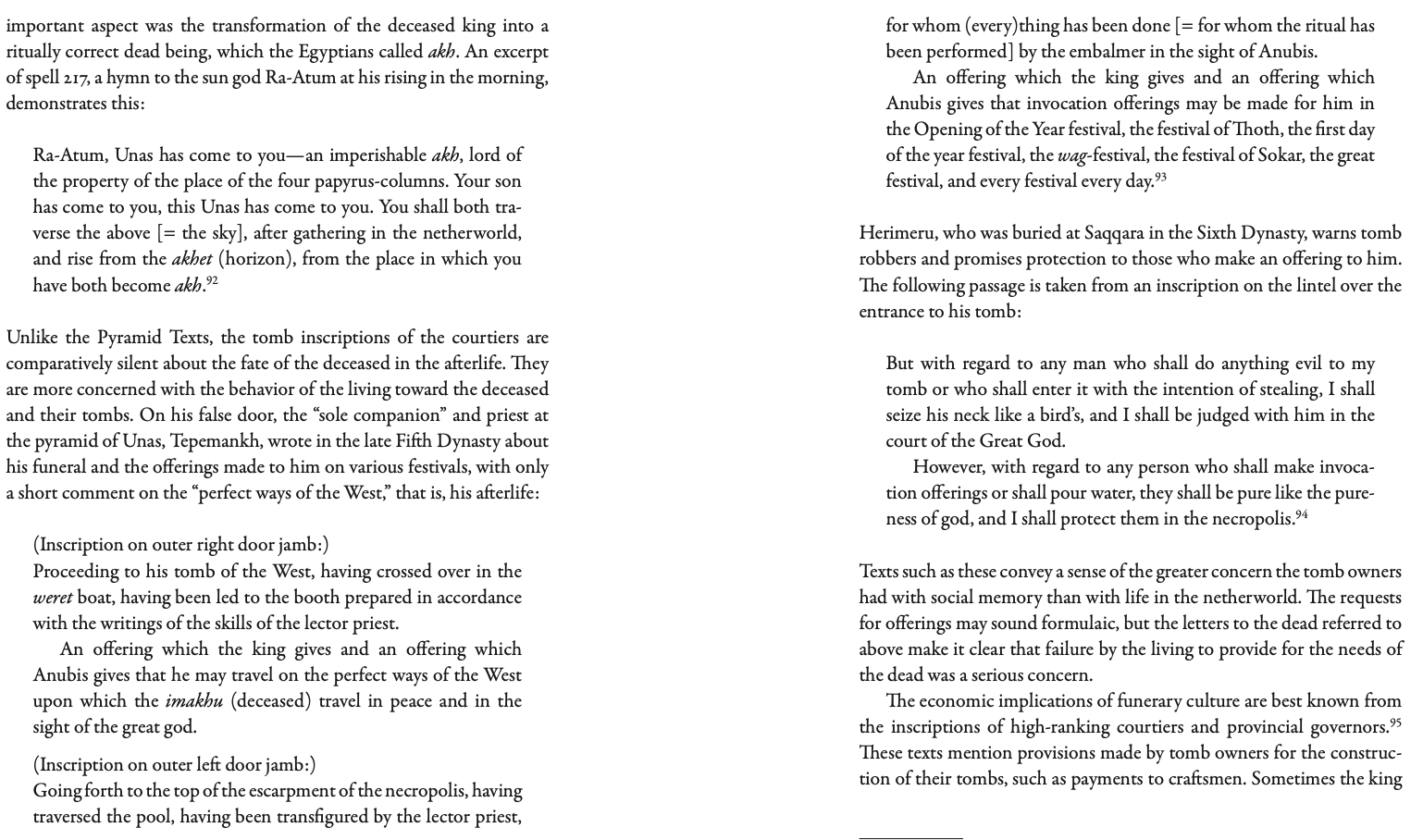

7.3. Funerary culture and society Tombs provide the largest body of archaeological evidence for the Old Kingdom. They range from the pyramids of kings and queens to the mau- soleums of the courtiers and from the tombs of provincial governors and their dependents to pot burials and bodies interred without either a cof- fin or grave goods. The diversity of funerary arrangements sheds a light on social organization that is different from the elite-centered perspec- tives of courtly display and administrative documents. Human remains and burial equipment add aspects of body practices to the picture but generally tell us little about the profession or activities performed by the deceased during their lifetimes, although these were probably most rel- evant for delineating an individual's place in a social group. Tombs are also places where funerary rites were performed. The wealth of preserved evidencearchaeological, visual, and written-raises hopes for under- standing the degree to which ritual practice can be understood to be an enactment of funerary beliefs. a The relevance of funerary data for social analysis has long been rec- ognized, but the approaches and assumptions underpinning them vary. The prehistorian Mike Parker Pearson remarked that funerals can reverse the social order of the living, so the burial of an individual may say little about his or her status in life. 58 Interpretive models in Egyptology empha- sizing the ritual nature of tombs also tend to disconnect the deceased from their social status during their lifetimes. Martin Fitzenreiter saw the funeral as a rite de passage that transformed the deceased into a new type of being and embedded him or her in the memory of the living. 59 Similarly, Jan Assmann viewed funerary rituals as a transformative prac- tice centered on the treatment of the body and social memory. Other approaches are more concerned with social analysis. John Baines and Peter Lacovara referred to the monumental tombs, ritual texts, and imagery of the elite as mausoleum culture.61 They believed that hardly any tombs of commoners have been found in Egypt so far, since almost all excavated burials display too high a degree of formality. According to Nicole Alexanian, tomb owners made arrangements for their tombs while they were still alive, as texts show.62 From a quantitative analysis of tomb sizes in provincial cemeteries, she concluded that a middle class had emerged toward the end of the Old Kingdom. Correlating tomb size and administrative titles, Naguib Kanawati assumed that the Old Kingdom state allotted tombs to its officials according to rank. His idea implies that the ranking system for the living translated directly into tomb size and that the central administration interfered considerably in the funer- ary arrangements of high-ranking officials.6 Basing his argument on evi- dence from a lower-status cemetery on the island of Elephantine island, Stephan Seidlmayer suggested that burial arrangements mirror social relationships known from elite display. He has moved the focus away from positioning deceased individuals in a hypothetical social struc- ture toward interpreting funerary culture as a language of relationships that both responded to and constituted social reality, an approach that informs the discussion below. The extant evidence is vast and context dependent. The following review is arranged in an inverse hierarchical fashion, beginning with the tombs of the lower social groups. These reveal the burial customs of a large proportion of the population, although they do not constitute the majority of known burials. Diachronic change is highlighted wherever possible in order to introduce some historical context. Guy Brunton and Reginald Engelbach excavated a cemetery at Gurob, in the Fayum, which Wolfram Grajetzki thought to be typical of rural communities in the Old Kingdom.66 The cemetery is located close to and below the modern (1920s) cultivation. The ninety-three recorded pits were found undisturbed and densely packed. They yielded few objects, often containing the body only, sometimes including a pot, a bead, or a basket. One headrest was discovered; in other cases, mud bricks, shards, or a pile of sand was placed under the head of the deceased. The bodies were usually found fully contracted, lying on the left side and wrapped in a mat. In total, fifty-four male adults, sixty-two female adults, thirty-four children, and six unidentified individuals were discovered. Their kin- ship relationships are unknown. No traces of above-ground architecture were found. The simple architecture and poor equipment of the burials at Gurob, the lack of a consistent alignment of the bodies to cardinal directions or with features of the local landscape, and the unfavorable location of the tombs close to the cultivated land threatened by the annual inundation all suggest that the tombs belonged to people of low status. However, the burials are not entirely informal. They are located in an area used a 58. Parker Pearson 1999: 39. a specifically as a cemetery, and the recurrent body position and wrapping in mats mirror distinct traditions. The tombs of Gurob are poor even in comparison to other nonelite burials, but they still comply with funer- ary conventions known from other sites. If culture is understood as a set of patterned practices, the evidence from Gurob would suggest that culture does not disintegrate into random informality at the lowest level of society. In 2009, a series of low-status cemeteries from the early Old Kingdom were surveyed in Middle Egypt.67 These stretch across 5 km on the escarpment of Deir el-Bersha and Deir Abu Hinnis. Hundreds of tombs were marked with stone boulders placed above and around the burial. The bodies were buried in reed or wooden boxes, pottery coffins, inverted pots, baskets, vats, and jars, usually set on the bedrock rather than in a subterranean pit. Textile remains suggest that some bodies were wrapped. The skeletons were identified as belonging to fetuses, infants, juveniles, and male and female adults between one and a half and fifty years old. A few alabaster vases; beads from shells, alabaster, carnelian, and faience; and some copper fragments were found, as well as a series of different types of pottery. The tombs and their contents were heav- ily disturbed by the rubble that had washed down from the desert hill. This makes it difficult to reconstruct the original tomb equipment of the deceased, most likely people who lived in a set of rural hamlets in the area around Deir el-Bersha and Deir Abu Hinnis. The cemeteries of Naga ed-Der, in Middle Egypt, offer a diachronic view of change at a local level. They are located on the low desert strip that runs for more than 2 km between the Eastern Desert plateau and the area of cultivation. The majority of tombs cluster around the mouth of the largest of the three wadis (valleys) that cut through the desert plateau. The local governors of the late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period were buried in rock tombs hewn higher up in the escarpment. Archaeological remains of the provincial capital and the villages to which the cemeteries belonged have not been discovered. Although the funerary record of Naga ed-Der spans a wide social spec- trum, it is likely that it overrepresents the middle to upper echelons of the local community.68 The Old Kingdom cemetery N500-900 is located on the northern flank of the wadi.9 The above-ground architecture is only preserved for the large tombs in the center, which date to the Third and early Fourth Dynasties. A stone bowl inscribed with the name of king Sneferu sug- gests that the individuals buried in these tombs had some contact with the central administration. The early Old Kingdom tombs display an array of different types, ranging from underground apartments reached via a stairway; through burials in large vats; to simpler pit burials, some of whose owners were, however, richly equipped. The bodies were usu- ally buried in a contracted position, lying on the left side or squatting in a vat. The late Old Kingdom tombs, in contrast, display greater confor- mity, consisting of a shaft and a rectangular chamber. The deceased were buried in a semi-contracted position, knees bent, facing left, often lying in a wooden coffin. The excavator George Andrew Reisner has argued that the introduction of rectangular coffins prompted the change in body positions.70 Technologically and on the level of equipment, the burials of the late Old Kingdom are poorer than the earlier ones and show less vari- ation. Either the same group of people changed its burial customs or, perhaps more likely, the later group represents a poorer segment of the population, whereas the higher-ranking segment had moved elsewhere. However, in absolute terms, these individuals cannot be said to have been poor because their families could afford coffins and amulets, some of which were made of costly stones. The cemeteries of Qau el-Kebir shed light on questions of gender and changing visual traditions in provincial Egypt from the late Old to the Middle Kingdoms. The cemeteries run north to south for a length of more than 20 km along the desert edge, and they belong to the rural communities that lived in this area.71 The majority of the preserved tomb shafts contained burials of women and children, sometimes in groups of two or three. The excavator, Guy Brunton, did not record the deep shafts that reached below the water table, or the empty shafts, whether plun- dered or undisturbed, that might have belonged to poorer people.72 The excavated record is probably best understood as representing the funerary customs of the lower to mid-ranking segment of the communities at Qau. Men, women, and children were buried with seals and amulets that they had presumably worn during their lifetimes. In the First Intermediate Period, hieroglyphic signs and symbols usually associated with kingship were adopted for seals and amulets, mirroring the appropriation of elite culture in a lower-status provincial context.73 Seals and amulets were used in magical spells and medical practice to protect women and chil- dren before, during, and after the life-threatening event of birth. The imagery was thus closely linked to bodily practices, particularly but not exclusively for women and children. In one of the tombs at Qau, Brunton discovered a bowl inscribed with a letter addressed to the deceased mother of the sender, who was called Shepsi.74 Shepsi accused his mother of stirring up his children against him, although he had offered her quail chicks as she had desired. Similar letters to the dead are known from other provincial sites of the Old and Middle Kingdoms.75 They show that the deceased were believed to interact with the living, who feared them. The issues addressed revolved around fertility, birth, diseases, inheritance, and arguments among fam- ily members. Deities were mentioned occasionally, kings never.76 Viewed together, seals, amulets, medico-magical practice, and letters to the dead conjure up an image of funerary culture, primarily in provincial Egypt, that focused on the body, physical well-being, and the close social sur- roundings by living individuals, rather than on kingship, the state, or piety toward the gods. The cemeteries of the First Cataract form a ranked social landscape. The cemetery on Elephantine Island, dated to the late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period, belongs to the lower social groups of the com- munity (for location, see figure 7.4 later in the chapter).77 No inscrip- tions were found here, and funerary investment was limited. The local upper elite of the same period was buried in decorated rock tombs, ca. 3 km upstream, at a site called Qubbet el-Hawa. Their followers apparently erected tombs at the foot of the causeways that led from the river up to the rock tombs, close to their patrons.78 The tombs of the lower-status island cemetery represent stereo- typed social models known from elite display.?' The excavator Stephan Seidlmayer has compared tombs with a single burial chamber to stat- ues of the early Old Kingdom depicting one individual, tombs with two chambers of equal size to statues depicting a husband and wife both of equal size, and tombs with several chambers of ranked size with late Old Kingdom statues of families whose members are depicted in vary- ing sizes. Tombs with sets of burial chambers of equal size might have belonged to families of followers of the local governors, who were buried close to their patrons at Qubbet el-Hawa. This interpretation implies that local rank overwrote family ties in determining funerary arrange- ments. In some cases, the tombs were populated with burials different from what the architectural model would suggest, indicating that reality was diverse and had to be accommodated within the restricted language of tomb architecture. discovered in the forecourt of the rock tombs. Upon visiting the tombs during festivals, the community would have encountered representations of the exclusive network of people that funerary culture spun around the local governors. Friedrich Rsing analyzed the human remains from Elephantine according to social groups. In total there were 1,487 individuals, of whom 578 were found in the Old Kingdom tombs of Qubbet el-Hawa, belong- ing to high-to mid-ranking individuals, and 153 in Old Kingdom tombs of the poorer island cemetery. 8 Diseases resulting from hunger, infec- tion, and genetic anemia were distributed evenly across all social groups. In contrast, body height seems to have varied significantly. The individu- als of the poorer island group were 6 cm shorter on average (158.3 cm) than the slender elites from Qubbet el-Hawa (164.6 cm). Rsing specu- lated that the local elite was not of local origin but had migrated from the capital to Elephantine. 8. He further observed that injuries were by far more frequent in the poorer population, including broken vertebrae due to prolonged compression, possibly resulting from hard labor; broken cheekbones, perhaps from military conflict; and broken noses and fore- arms, typical of females and probably deriving from domestic violence. Despite biases in the record, such as an overrepresentation of lower-class women and of adult men in the elite class, these trends seem to be robust overall. They demonstrate that all members of the local community had rather similar lives, but that the lower social groups experienced greater physical stress. The tombs of the local elite at Qubbet el-Hawa, dated to the late Old Kingdom and later, offer a visual glimpse into the local community of Elephantine. 82 They are arranged in terraces from which the rock-cut chapels were entered. Their walls are decorated with panels depicting the tomb owners, members of their households, and other individuals, many labeled as funerary priests and others bearing mid-ranking administrative titles. The majority of panels depict offerings made to the tomb owners. Although not all individuals bear names and titles, it has been suggested that they were members of the tomb owners' households engaged in the mortuary cult for their patrons. Some may have been buried in the shafts In Dakhla oasis, the Sixth Dynasty central administration installed a governor whose duty it was to control movements on the tracks run- ning through the Western Desert to the Nile valley.83 A residence and a set of large tombs were erected for the governors in the eastern part of the desert, at Ayn Asil and Qila el-Dabba, close to Balat. Earlier remains of a campsite of the local Sheikh Muftah culture, discovered near Balat; remains of an Egyptian settlement in the western part of the desert, at Ayn el-Gezareen; and a set of hilltop sites, used for controlling the desert routes, suggest that the governor's residence was placed in an existing infrastructure.84 Links to the Memphite court are strong in this rather remote des- ert area. The five tombs of the governors at Qila el-Dabba are complex, monumental mud-brick structures, each occupying an area of 400 to 700 sq m. Two have a set of oblong chapels placed next to each other, imitating the architecture of royal pyramid temples. Governors' buri- als were equipped with calcite vessels inscribed with royal names. The stone and pottery vases found in the burials and some preserved remains of tomb decoration also follow court standards. The secondary burials located in the forecourts and outside the tombs probably belonged to wives and other household members of the governors and perhaps some of their dependents. 85 Their names and titles are not recorded on the objects, either because of their comparatively low status or because they died after the collapse of the central administration at the end of the Old Kingdom, or for both reasons. Administrative documents from Balat show several ranks of officials below the governor, but this structure is not reflected in the funerary organization. Perhaps the middle class of officials was buried near Ayn el-Gezareen. At court, the Western Cemetery of Giza, behind the Khufu pyramid of the Fourth Dynasty, became popular again in the late Fifth Dynasty. Ann Macy Roth has published a cluster of forty-one stone-lined tombs of mid-ranking palace attendants and their overseers, mentioned ear- lier in this chapter.S6 Each tomb has one principal burial shaft and a series of shallower shafts ending in burial chambers. The communities buried in them were imagined by the tomb builders to be ranked households, consisting of one main person and several dependents of equal status irre- spective of gender, age, and status. Women depicted together with the male tomb owners on the walls of the above-ground chambers are rarely labeled as wives. Other individuals are labeled as sons, daughters, sisters, and funerary priests. Those buried in the shorter shafts may have been dependents. It seems from the analysis of human remains that despite the high mortality rate that has been generally assumed for children in ancient Egypt, all the individuals buried here died at the age of eight years or older (the analysis was based on photographs). 87 If sons and daughters were buried in the shallower shafts, they must have reached adulthood or nearly so, which is not what their depictions on the tomb walls would suggest. In other words, there is a mismatch between the community depicted on the tomb walls, the community represented in tomb architecture, and the people that were actually buried in the shafts. According to the names and titles recorded on the walls, the princi- pal tomb owners in this cluster were related to each other through their office rather than through family ties. The highest-ranking group of over- seers owned tombs with an area of up to approximately 90 sq m, whereas the superstructure of ordinary palace attendants was only around 35 sq m-still monumental compared to the vast majority of tombs in provin- cial cemeteries. Otherwise, there is only a weak correlation between sta- tus and other features, such as the volume of the subterranean chambers or of the chapel. Thus, not all quantifiable features are equally relevant for social analysis. Wooden and stone coffins were found only in principal shafts, although some bodies in the shallower shafts were placed in wooden boxes. Other shallow shafts were empty and perhaps never used. The material used to fill the shafts after the funeral, which has not been ana- lyzed in detail, is described as varying from shaft to shaft. Several stat- ues of tomb owners were found, some in their original location in the serdab, a chamber built for these statues only and later sealed. The tombs decayed fairly soon, by the early Sixth Dynasty, and the offering cult for the deceased probably ended around the same time. The tomb of Netjeraperef at Dahshur shows the degree to which the iconography of elite funerary ritual and the archaeological record over- lap. 88 Netjeraperef was a son of king Sneferu. His large tomb is located at the edge of a cluster of tombs arranged rigidly in three rows. Its east face, which looked toward the world of the living, had two cult niches, the southern of which was larger and protected by a secondary mud- brick wall (see figure 7.3). Two rows of postholes were found south of the tomb. A mud-brick ramp attached to the western face led to the roof of the tomb. From there, a shaft descended to the burial chamber, which was locked with a large stone slab. In front of the entrance to the burial chamber, the excavators found an incense burner, a ritual vessel called nemset in Egyptian, miniature copies of vessels and storage jars, a set of small alabaster plates, a shard (perhaps used for some ritual preparation), a loaf of bread made of clay, and the bones of a calf. The same types of vessels and food are depicted in offering scenes in elite tombs. Nicole Alexanian therefore speculated that a single ritual was enacted in front of the burial chamber in order to initiate the mortuary cult. 89 Many bread molds, beer jars, and pot stands were found scattered on the surface around the tomb. This material probably derives from the funeral itself rather than from the mortuary cult performed after the funeral. There is only weak evidence for pottery of this type that defi- nitely dates to later than the early Fourth Dynasty when Netjeraperef ramp postholes tent similar to the posthole structure encountered south of the tomb of Netjeraperef. Although the overlap of image and material remains is exceptional in this particular case, it is conditioned by the fact that they articulate ideas and practices within the same social milieu at court. Astonishingly little is known about the funerals of kings, although these must have been major events. Some of the depictions on the walls of the pyramid complexes, such as images of the king seated in front of a row of offering bearers, could refer to either the regular mortuary cult or the funeral itself. Since the regular mortuary cult in the pyramids was closely linked to the administration and the state, it is considered in chapter 5. Some of the spells in the Pyramid Texts contain instructions for ritu- als carried out during the royal funeral. Their primary interest to us lies in the interpretation of the ritual. In the following passage from the ritual for Opening the Mouth, probably of the royal mummy or a royal statue, the deceased king Unas is identified with Osiris and the object offered to him with the eye of Horus. The return of this eye to Osiris symbolizes the restitution of the cosmic order, a figure of thought that dominates the later theology of temple cult and is attested in writing for the first time in the Pyramid Texts. Spells 46 and 47 give instructions, interpret the offering, and mention the object offered: DESEN v. cult chapel 10m SOS burial shaft burial chamber blocking stone FIGURE 7.3. Tomb of prince Netjeraperef, early Fourth Dynasty. Plan and sec- tion. After Alexanian 1999: fig. 4 and 5. Courtesy Deutsches Archologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo. 4 90 was buried. The funerary cult seems to have ended fairly soon after Netjeraperef died, a reality of which Egyptians must have been aware." Alexanian showed that the archaeological evidence from the tomb overlaps with the depiction of a funeral in the tomb of a court official called Debeheni, from the end of the dynasty. The scene shows a row of offering bearers climbing a ramp onto the roof of the tomb; a series of bread molds, beer jars, and offering stands arranged along the foot of the tomb; and various individuals performing rituals in a temporary To be recited four times: A royal offering to the ka (the soul) of Unas: Osiris Unas, accept Horus's eye, your bread-loaf, and eat." A loaf of offering bread. Osiris Unas, accept Horus's eye, which escaped from Seth, which you should take to your mouth and with which you should open your mouth. One bright quartzite jar of wine. 91 genres remod- a The Pyramid Texts embrace a broad range of themes and eled and recontextualized over the following three millennia. An important aspect was the transformation of the deceased king into a ritually correct dead being, which the Egyptians called akh. An excerpt of spell 217, a hymn to the sun god Ra-Atum at his rising in the morning, demonstrates this: for whom (every)thing has been done [= for whom the ritual has been performed] by the embalmer in the sight of Anubis. An offering which the king gives and an offering which Anubis gives that invocation offerings may be made for him in the Opening of the Year festival, the festival of Thoth, the first day of the year festival, the wag-festival, the festival of Sokar, the great festival, and every festival every day. 93 Ra-Atum, Unas has come to youan imperishable akh, lord of the property of the place of the four papyrus-columns. Your son has come to you, this Unas has come to you. You shall both tra- verse the above [= the sky], after gathering in the netherworld, and rise from the akhet (horizon), from the place in which you have both become akh.92 Herimeru, who was buried at Saqqara in the Sixth Dynasty, warns tomb robbers and promises protection to those who make an offering to him. The following passage is taken from an inscription on the lintel over the entrance to his tomb: Unlike the Pyramid Texts, the tomb inscriptions of the courtiers are comparatively silent about the fate of the deceased in the afterlife. They are more concerned with the behavior of the living toward the deceased and their tombs. On his false door, the sole companion and priest at the pyramid of Unas, Tepemankh, wrote in the late Fifth Dynasty about his funeral and the offerings made to him on various festivals, with only a short comment on the perfect ways of the West," that is, his afterlife: But with regard to any man who shall do anything evil to my tomb or who shall enter it with the intention of stealing, I shall seize his neck like a bird's, and I shall be judged with him in the court of the Great God. However, with regard to any person who shall make invoca- tion offerings or shall pour water, they shall be pure like the pure- ness of god, and I shall protect them in the necropolis.94 (Inscription on outer right door jamb:) Proceeding to his tomb of the West, having crossed over in the weret boat, having been led to the booth prepared in accordance with the writings of the skills of the lector priest. An offering which the king gives and an offering which Anubis gives that he may travel on the perfect ways of the West upon which the imakhu (deceased) travel in peace and in the sight of the great god. (Inscription on outer left door jamb:) Going forth to the top of the escarpment of the necropolis, having traversed the pool, having been transfigured by the lector priest, Texts such as these convey a sense of the greater concern the tomb owners had with social memory than with life in the netherworld. The requests for offerings may sound formulaic, but the letters to the dead referred to above make it clear that failure by the living to provide for the needs of the dead was a serious concern. The economic implications of funerary culture are best known from the inscriptions of high-ranking courtiers and provincial governors.95 These texts mention provisions made by tomb owners for the construc- tion of their tombs, such as payments to craftsmen. Sometimes the king for the continuation of mortuary cults for very long after the funeral, at least not in the form of identifying material remains. Funerary culture in the Old Kingdom was a multifaceted phenome- non. At court, many tombs were monumental, and the burial customs dif- fered from those in the hinterland. Practices centered on statues were far more widespread among kings and courtiers than in provincial Egypt.99 Funerary beliefs are not salient in Old Kingdom written evidence, unlike the situation for later periods. Such beliefs could overlap with funerary practices and their representations in writing and art, but they hardly explain the diversity of burial arrangements in different social groups. 7.4. Urbanism is said to have allocated a tomb to an official or to have had a door or sar- cophagus made for him, apparently an exceptional honor worth record- ing in one's biography. Kings also set up foundations that delivered supplies for the mortuary cult of high-ranking courtiers.96 After being offered, the food was then distributed among the funerary priests. In the later Old Kingdom, some viziers and other court officials organized their funerary priests in phyles (working gangs), imitating the system in which royal funerary priests were organized. 97 The arrangements made for funerary priests were a dominant subject in non-royal legal texts of the Old Kingdom.98 Funerary priests need not have been members of the family, a situation that might have necessi- tated making the arrangement explicit in writing. A well-known example is the regulation for his mortuary cult by the local governor of the early Fifth Dynasty at Tehna called Nykaankh, who was chief priest at the local temple of Hathor. Nykaankh decreed that his wife and his nine chil- dren were entitled to the income from his funerary foundation during ten months of the year. During the eleventh month, a priest of Hathor received the income, and two other individuals, one labeled funerary priest, shared the income during the twelfth month. The inclusion of a priest from the Hathor temple, the cult of which was sponsored by the king, shows that the funding of the local temple and of the mortuary cult for the local governor overlapped. Local economic resources were prob- ably seen as lying more with individuals than with institutions. It is more difficult to reconstruct the economic organization of the funerary cult for the majority of the population, for which written docu- ments are not available and probably did not exist. One might imagine family members making offerings to their ancestors, although different arrangements for the mortuary cult made orally in the presence of wit- nesses are also a possible scenario. There is little archaeological evidence In comparative debates on early civilizations, urbanism is seen as a key indicator of social complexity.100 Cities provided a context for craft spe- cialization, bureaucracy, and ritual performance controlled by emergent elites.101 Types of urbanism differ cross-culturally. Old Kingdom Egypt is described as a territorial state with one urban center at Memphis and a series of smaller towns and villages scattered along the river Nile, exhib- iting a primate rank-size distribution, as opposed to the city-state civili- zations in Mesopotamia, Mesoamerica, and the Indus valley, which are characterized by a polycentric pattern. The primate rank-size distribution provides a useful context for modeling settlement geography in Old Kingdom Egypt. However, taken at face value, it finds limited support in the archaeological record. The city of Memphis has not been identified so far, while villages, hamlets, and agricultural estates, which would classify as third-rank settlements in the model, are archaeologically elusive. Social hierarchies, ritual per- formance, and the division of labor are obvious from written and visual 102 a