Question: Create multiple paragraphs about Egyptian culture. Use the information below. interdependence of practices and representations, everyday strategies of appropriation, and small-scale contexts of historical inquiry.10

Create multiple paragraphs about Egyptian culture. Use the information below.

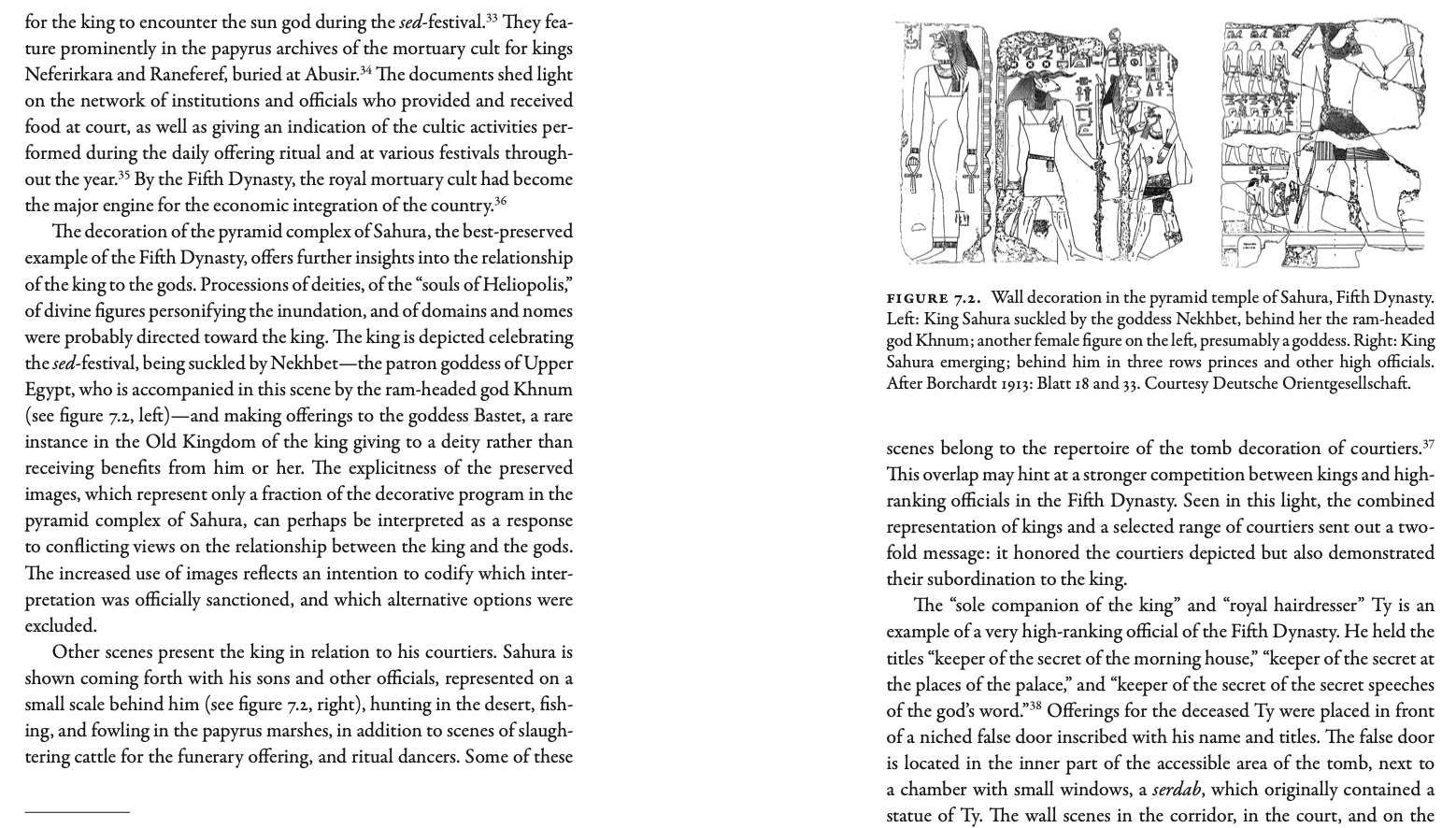

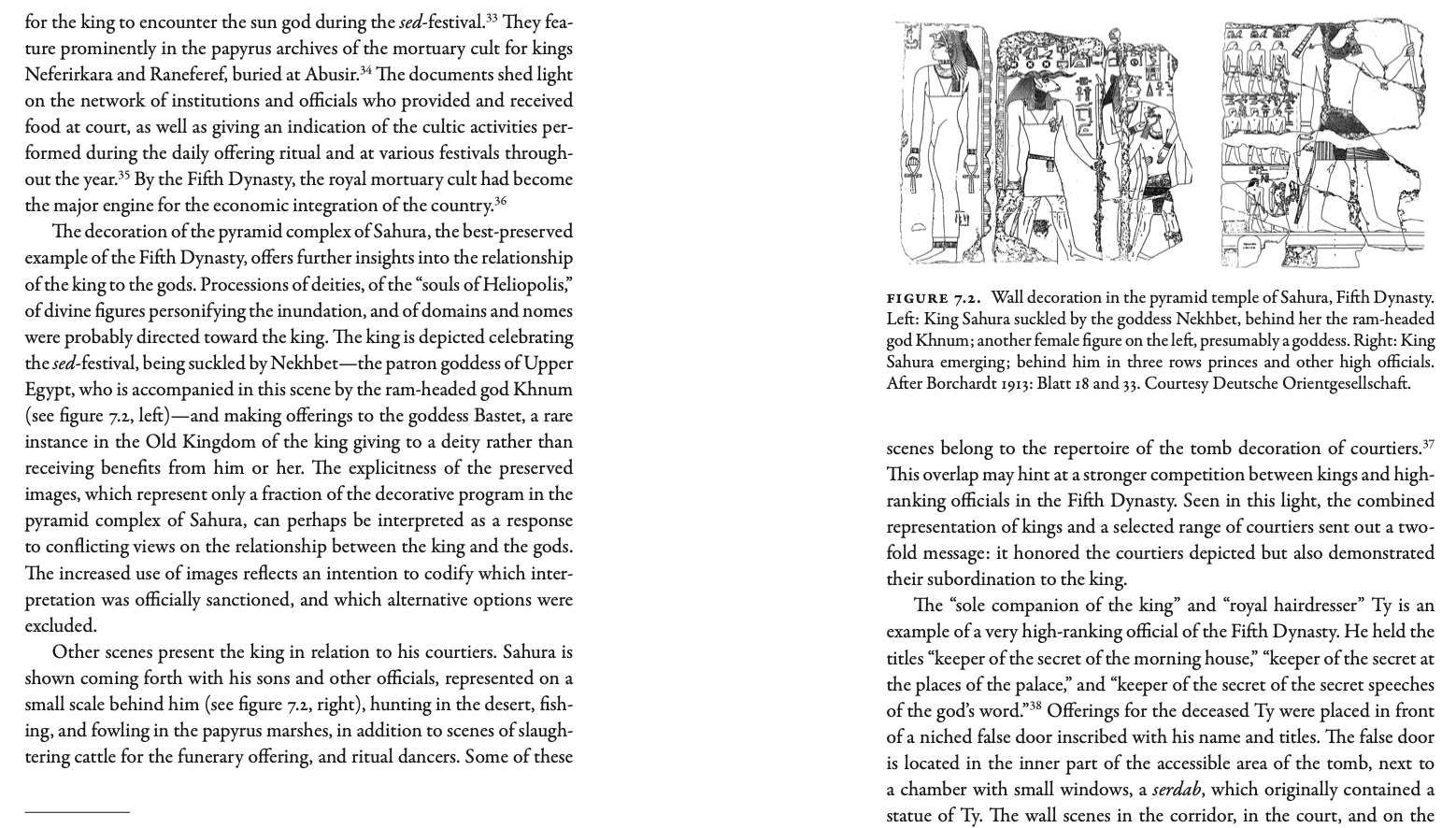

interdependence of practices and representations, everyday strategies of appropriation, and small-scale contexts of historical inquiry.10 Drawing on these debates, this chapter takes as a guiding principle the diachronic development of, and exchange between, central and local milieus. It explores to what extent social conditions shaped the produc- tion of knowledge and offers a glimpse of both the diversity and coherence within Old Kingdom society. The first section (section 7.2) outlines changes in royal ideology and court society. The second section explores funerary culture, emphasizing social diversity as well as considering questions of funerary belief and diachronic change. The discussion of settlements in the third section adopts a typological and chronological perspective on urban growth. The fourth section develops thoughts on cultural diversity and the role of provincial community shrines, followed by an outline of the early nomarchy in the fifth section. The final section offers a broader view of some principal features of Old Kingdom society and culture. a The following paragraphs are not much concerned with the history of the state, the administration, and the complex system of rank at court, studied extensively on the basis of prosopography.2 Rather, here the aim is to outline the diachronic development of the courtly milieu as a whole. 13 Kingship is embedded in and at the center of court society, which is why the two phenomena are best discussed together. 14 The Old Kingdom is particularly susceptible to being interpreted in terms of sacred kingship because of the superhuman monumentality of royal pyramids and because kings of the Old Kingdom were designated netjer, a word conventionally translated as god in English. At the level of iconography, kings and gods are depicted with similar attributes that set them apart from others. However, royal epithets and activities differ from those of deities. Kings appear not to have been gods but only to have interacted with them face to face. Overall, Old Kingdom monu- ments focus on demonstrating what the king is, whereas there is little presentation of what a deity is beyond his or her relationship to the king. Speculative thought was dominated by royalogy much more than by theology," a realm of discourse that unfolded only in the later religious history of Egypt. 15 Earlier discussions of sacred kingship in anthropology and Egyptology culminated in Henri Frankfort's comparative Kingship and the Gods.16 Despite the merits of this book, its weak consideration of historical context and the imbalance of religious and monumental evi- dence used for Egypt, in opposition to its use of administrative texts for Mesopotamia, make it a difficult source for modeling kingship in the Old Kingdom and its development through time. 7.2. Kingship and court society Most of the evidence for Old Kingdom kingship and court society comes from funerary contexts and ranges from the architecture of pyramids, the tombs of courtiers, and the statues associated with them to tomb decora- tion and inscriptions. Of the settlements in which these courtiers lived there are only a few preserved remains, and no remains of royal palaces have so far been identified in the archaeological record. To what degree inferences about kings and courtiers based on their tombs would be cor- roborated by evidence from other contexts is difficult to say. However, it would be wrong to disregard the available material as reflecting only ideology or funerary concepts. A more productive approach is to under- stand elite culture, or high culture," as a discourse with its own dynam- ics and practices articulated predominantly in Old Kingdom funerary contexts but embracing non-funerary themes as well." 12. Baer 1960; Kanawati 1977; Strudwick 1985. 13. "Court society is defined in this chapter as the community at court, following Elias 1969. a Wolfgang Helck believed that the prehistoric ancestors of Egyptian kings were purely divine beings and only descended into the world of humans during the Old Kingdom, when the state became increasingly complex and power had to be shared with non-royal officials."7 His argu- ment has been extended into the Middle Kingdom by scholars who have argued that the explanation of kingship in Middle Kingdom literature reflects a growing mistrust in an institution that was uncontested dur- ing the Old Kingdom. 18 While the negotiation of kingship in literary texts might indeed reflect a higher degree of contestation, archaeologi- cal and pictorial evidence from the Old Kingdom shows that kingship evolved throughout the third millennium BC and that different options for thinking about kingship were already available at that time." Unlike Helck, the anthropologist Declan Quigley has argued that kings have to be actively made into beings of a different order, often in ways that may seem irrational, for example, by overloading them with gold and jewelry or not allowing them to touch the ground.20 Kings may not be involved in political decision-making, yet they still represent the cosmic and ritual well-being of society, reigning rather than ruling. According to Quigley, social ties, for example to their families, can be severed so that all members of society are able to relate equally to the king. Quigley's model may not describe Old Kingdom kingship very well. Royal family ties, for example, remained important throughout the Old Kingdom.21 The available sources tell us very little about the role of kings in day-to-day political business, not even in the New Kingdom, for which source material is more abundant.22 However, Quigley has raised the question that forms the analytical focus of the following out- line: How was the king positioned in relation to others? In particular, how were new relationships established and negotiated between kings and gods on the one hand, and kings and courtiers on the other? The iconographic display of Egyptian kingship is attested at least as early as the Narmer Palette, dedicated to the falcon god Horus, from the temple precinct of Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt. On one side of the palette, the king is represented facing a falcon figure, and his name is written in a ser- ekh (rectangle representing a palace facade) surmounted with a depiction of Horus. On the reverse side, the king is shown with distinct royal rega- lia, accompanied by his courtiers depicted on a smaller scale. This arrange- ment is paralleled in the spatial organization of the royal tombs of the First Dynasty at Abydos. Each tomb is surrounded by rows of subsidiary burial chambers of equal size. Similar arrangements are known from non-royal tombs, such as those at Saqqara, Naqada, Tarkhan, Giza, and Abu Rawash. If one considers all the Early Dynastic material together, setting aside poten- tially conflicting evidence, the relationship between the king and the gods is not entirely explicit. It may be described as an association of the reigning king with Horus in the case of the Narmer Palette. Comparatively speak- ing, the relationship to the courtiers is clearer. The king is embedded in the community of the courtiers, who are imagined as being equal, or almost so, among one another regardless of their actual age, gender, or position at court. The imitation of royal funerary arrangements by non-royal indi- viduals suggests that the relationship kings had to their courtiers was not an exclusively royal model. The situation changed significantly at the beginning of the Third Dynasty. The step pyramid of king Djoser at Saqqara has no equal in the country. It is set in a large plaza lined with dummy chapels and used for the sed-festival, a ritual to celebrate kingship. The plaza continues a tra- dition of similar open courts known since the late Predynastic period. 23 Scenes of the ritual displayed on panels in the subterranean chambers below the pyramid depict rituals of the sed-festival that were probably performed in this open courtyard. The panels show the king standing in 17. Helck 1954 18. Posener 1956; Assmann 1990: 54-57. 19. Baines 1997; Stockfisch 2003. a front of chapels identical to those that line the plaza above ground. 24 The chapels and the depiction of standards and falcons surrounding the king imply divine presence. Fragments of a small shrine dedicated by Djoser in the temple of Heliopolis show the king seated with his wife and daughter facing a group of gods.25 The deities hand over life, dominion, sed-festivals, and other royal prerogatives to the king. They probably belong to the Heliopolitan Ennead. a group of nine deities from different generations beginning with the sun god Atum, who created the world, and ending with Horus, the reigning king. The decoration of the shrine asserts emphatically that kingship is derived from the gods. Moreover, it presents the world of the gods as structured around kingship. In other words, the institution of kingship was divinized as much as the gods were royalized. During the Fourth Dynasty, the pyramid and court cemeteries moved more than 70 km from Meidum in the south to Dahshur, Giza, and Abu Rawash in the north, then back to Giza and finally to Saqqara.26 Since the location of the royal palace and the living quarters of the court- iers is not known, it is difficult to say whether the courtiers lived where they were buried and whether this influenced the choice for the location of the corresponding royal cemetery.27 However, the migration indicates that court society was relatively mobile and not yet as intimately tied to a place as it was in later dynasties. Khufu, the second king of the Fourth Dynasty, built a gigantic pyra- mid at Giza surrounded by smaller pyramids for the queens, very large tombs for the princes to the east, and smaller tombs for other court- iers to the west of the pyramid. 28 Differing from the royal tombs of the First Dynasty, the Giza cemetery embodies a ranked court community. Khufu restricted the tomb decorations of courtiers to only a simple slab mounted above the offering niche. Hermann Junker coined the term austere style to describe the appearance of the tombs.29 According to Junker, all attention was meant to be directed toward the pyramid of the king rather than to the splendor of his courtiers. Later additions, changes, and the use of tombs by individuals different from those for whom they were planned demonstrate the difference between the imagined model and actual practice. Social engineering, as reflected in the Khufu cem- etery, looked back to similar attempts under his predecessor Sneferu, but it does not seem to have been a standard practice in later dynasties. 30 Major social processes at the royal court of the Fourth Dynasty can be recognized in the centralization and stratification of the core elite. On the level of ideology, royal names refer increasingly to the sun god Ra. The designation of the king as son of Ra," later a popular royal title, is first attested in the reign of Radjedef and implies a subordinate position of the king to the sun god. A group of statues from the valley temple of Menkaura show the king flanked by the goddess Hathor and deities sym- bolizing a nome. 31 Nome symbols followed by female offering bearers, each representing a royal domain, are also displayed on the earlier reliefs in the valley temple of king Sneferu. Nomes and domains were thus the entities by which the crown conceptualized and shaped the hinterland of Egypt for the purposes of taxation and funding the royal mortuary cult. Whereas in the early Old Kingdom the deceased kings were provisioned with offerings placed in their burial apartments, the focus shifted in the Fourth Dynasty toward the mortuary cult carried out after the funeral. 32 The Fifth Dynasty marks a turning point in the history of king- ship and the court on various levels. The kings of this dynasty built sun temples close to their pyramids to strengthen their ties to Ra. Given the tradition of associating the royal tomb with structures for celebrating kingship, the sun temples are perhaps best understood as cultic arenas TAFEY 35 for the king to encounter the sun god during the sed-festival.33 They fea- ture prominently in the papyrus archives of the mortuary cult for kings Neferirkara and Raneferef, buried at Abusir.34 The documents shed light on the network of institutions and officials who provided and received food at court, as well as giving an indication of the cultic activities per- formed during the daily offering ritual and at various festivals through- out the year.?" By the Fifth Dynasty, the royal mortuary cult had become the major engine for the economic integration of the country.36 The decoration of the pyramid complex of Sahura, the best-preserved example of the Fifth Dynasty, offers further insights into the relationship of the king to the gods. Processions of deities, of the souls of Heliopolis," of divine figures personifying the inundation, and of domains and nomes were probably directed toward the king. The king is depicted celebrating the sed-festival, being suckled by Nekhbetthe patron goddess of Upper Egypt, who is accompanied in this scene by the ram-headed god Khnum (see figure 7.2, left)and making offerings to the goddess Bastet, a rare instance in the Old Kingdom of the king giving to a deity rather than receiving benefits from him or her. The explicitness of the preserved images, which represent only a fraction of the decorative program in the pyramid complex of Sahura, can perhaps be interpreted as a response to conflicting views on the relationship between the king and the gods. The increased use of images reflects an intention to codify which inter- pretation was officially sanctioned, and which alternative options were excluded. Other scenes present the king in relation to his courtiers. Sahura is shown coming forth with his sons and other officials, represented on a small scale behind him (see figure 7.2, right), hunting in the desert, fish- ing, and fowling in the papyrus marshes, in addition to scenes of slaugh- tering cattle for the funerary offering, and ritual dancers. Some of these FIGURE 7.2. Wall decoration in the pyramid temple of Sahura, Fifth Dynasty. Left: King Sahura suckled by the goddess Nekhbet, behind her the ram-headed god Khnum; another female figure on the left, presumably a goddess. Right: King Sahura emerging; behind him in three rows princes and other high officials. After Borchardt 1913: Blatt 18 and 33. Courtesy Deutsche Orientgesellschaft. scenes belong to the repertoire of the tomb decoration of courtiers. 37 This overlap may hint at a stronger competition between kings and high- ranking officials in the Fifth Dynasty. Seen in this light, the combined representation of kings and a selected range of courtiers sent out a two- fold message: it honored the courtiers depicted but also demonstrated their subordination to the king. The sole companion of the king and royal hairdresser Ty is an example of a very high-ranking official of the Fifth Dynasty. He held the titles keeper of the secret of the morning house." keeper of the secret at the places of the palace, and keeper of the secret of the secret speeches of the god's word.38 Offerings for the deceased Ty were placed in front of a niched false door inscribed with his name and titles. The false door is located in the inner part of the accessible area of the tomb, next to a chamber with small windows, a serdab, which originally contained a statue of Ty. The wall scenes in the corridor, in the court, and on the pillars show different stages of the funerary ritual, such as offering bear- ers, processions with the statues of Ty and dancers, and a procession of domains delivering food for the mortuary cult, as well as an image of Ty being carried in a palanquin, an almost exact copy of a scene from the pyr- amid complex of king Nyuserra. Other scenes depict Ty fishing, fowling, or supervising craftsmen engaged in various activities such as woodwork- ing, manufacturing cylinder seals, pottery making, and administration, and people producing food, such as fishermen and peasants. The range of scenes is broad but highly selective. The activities repre- sented emphasize the public contexts of Ty's life, in which his wealth was particularly overt. Ty is not shown interacting with his peers, parents, the king, or a deity. Apart from the female members of Ty's household, very few women are depicted. His wife, the sole female companion of the king and priestess of Hathor, is only shown in a subordinate posi- tion to her husband. The entire decoration of this tomb, like other court tombs, is developed from the perspective of a high-ranking male courtier. Tomb inscriptions and decoration refer to real events in the life of a courtier as much as they reflect practices of imitating, copying, and modifying images and texts displayed in the tombs of other courtiers. A cluster of late Fifth Dynasty tombs at Giza, of much smaller size than the tomb of Ty, shows signs of interaction within a group.99 The owners of these tombs are related to each other not by family ties but by their shared office. They are all palace attendants. Idiosyncratic stylistic fea- tures suggest that the same artist or workshop decorated the tombs. One can speculate that the members of this community observed each other before making decisions on the selection and placement of scenes. If adherence to shared standards had greater value than individual choice, peer observation might have contributed to restricting the range of themes displayed in inscriptions and scenes. In this competitive climate, the biography, a productive text genre throughout pharaonic history, was further developed as a means for self-representation. Biographies of the early and mid-Fifth Dynasty emphasize the generosity of the king toward the official whose life is recorded. The chief physician Nyankhsekhmet proudly claimed that the king had two false doors of high-quality limestone from Tura brought for him.41 Direct interaction with the king was honorable but potentially difficult. The sem priest and keeper of ritual equipment Rawer was touched by the king's scepter (or he damaged it), whereupon the king, according to a royal decree displayed in Rawer's tomb, gave reassurance that this incident should not have negative consequences for him.42 Another official, Washptah, was struck by a seizure during a royal inspec- tion and was allowed to kiss the king's feet rather than only the ground before his feet.3 These examples demonstrate that the physical body of the king and his regalia were imbued with dangerous power.4 In the later Fifth Dynasty, two principal types of biographies emerged, the career biography and the ideal biography.45 Career biographies mention promotion in office awarded by the king or missions carried out for him, although direct interaction with him as in the examples above is exceptional. In contrast, ideal biographies express the courtier's com- mitment to social and religious norms. The formulae used in ideal biog- raphies, as in the following passage from the early Sixth Dynasty tomb of Kaiaper at Saqqara, laid the foundation for the ethics of the nomarchs in the First Intermediate Period: I came forth from my town, I went down from my nome. I did justice for its lord, I satisfied the god with what he loves. I gave bread to the hungry, clothes to the naked. 41. Strudwick 2005: 302303, no. 225; early Fifth Dynasty. 42. Strudwick 2005: 305-306, no. 227. I ferried the one who had no boat. I speak what is good and repeat what is good.46 47 The development of career and ideal biographies during the Fifth Dynasty is interpreted here as a strategy by courtiers to define new modes of distinction in a period when court society had begun to coalesce and the range of titles had expanded. The end of the dynasty demarcates a leap in the written traditions of the Old Kingdom. King Unas is the first king who had Pyramid Texts written on the walls of his burial apartments. The texts were copied from papyrus documents and embrace a range of types, such as ritual instruc- tions and sacerdotal texts used for the royal funeral and apotropaic spells.7 Key ideas that might have long predated the inscription of the texts in the royal burial chambers revolve around the identification of the deceased king with Osiris, the lord of the netherworld, and the king join- ing the solar barge to travel with the sun god and his crew over the sky. The reference to Osiris suggests that the Osiris myth, which negotiates difficulties of the royal succession, had developed by this time. The Pyramid Texts probably derived from a corpus of texts written on a variety of media.48 The reasons for inscribing them in the royal burial chambers are obscure. Harold Hays argued that this entextual- ization,as he termed it, reflects an extension in the usage of the texts from practice to knowledge. *' Knowledge was important social currency for distinction at court, as indicated by the widespread title hery-sesheta (keeper of the secret), which Ty, for instance, bore. S Hays pointed out that certain ideas articulated in the Pyramid Texts, especially the ritual transformation of the dead individual into a secure deceased being, were shared between kings and courtiers, implying that royal funerary beliefs were less exclusive than is usually assumed in Egyptology. Perhaps the recording of Pyramid Texts can be interpreted as a further means of set- ting the king apart from rival courtiers in a period when the differences between the king and his close entourage began to diminish. In the Sixth Dynasty, central administration engaged more closely with provincial affairs. Court officials were sent into the hinterland as local administrators and started settling there permanently. They brought ideas and modes of courtly display with them. Although the decoration and biographies in their tombs made references to local con- texts, in essence these officials were courtiers. 51 An intriguing example of such an official is Weni. He was promoted from a lower-ranking court office under king Teti to overseer of Upper Egypt under Pepy I. His career shows that social mobility was possible to a certain degree, at least within the upper administrative apparatus. Weni was not buried at Saqqara, where blocks inscribed with a fragmentary copy of his long biography have come to light, but in his tomb at Abydos in the Eighth Upper Egyptian nome. 52 According to his biography, he had the privilege of witnessing alone, with just one other official, a legal case dealing with a conspiracy in the royal harem. He led military and other missions for the king to Nubia, to the alabaster quarries in Hatnub, and to the Sinai. Apart from providing information on historical events, the biography sheds light on the changing milieu at court in the Sixth Dynasty. Christopher Eyre remarked that the ruling class had become large and complex by then and hypothesized that Weni, a grey eminence in his old age and a potential threat to the power of the king, was side- lined and sent to the province.93 The more pronounced role of the provinces in court display was paralleled in a new relationship between the king and the gods. The decoration in the pyramid complex of Pepy II is the best preserved from the Sixth Dynasty. One scene shows a series of deities emerging from their chapels and proceeding to the king. 54 Although most of the names of the deities and their locations have been destroyed, the scene might indicate that it is not the gods alone who were directed toward the king but, institutionally, the provincial temples whose patrons they were. The archaeological reality of this interpretation is discussed below Yet the model calls for a close observation of the selective mechanics of elite genres, which needs to be set against a less ordered reality. Jan Assmann placed the beginning of what he called "monumental dis- course in the Old Kingdom.56 The term designates the changing themes and intertextual nature of the written traditions in ancient Egypt. Taking as his point of departure the tomb biographies of Old Kingdom court- iers, Jan Assmann proposed that ancient Egyptian literature originated in a funerary context and was tied to the remembrance of the deceased. According to Assmann, monumental discourse laid the foundation of social memory in Old Kingdom society and, in the long run, of cultural memory today. Despite its idealizing underpinnings, this model shows 57 how social developments at the court of the Old Kingdom might feed into discussions of world history. in section 7.5. The diachronic outline of the courtly milieu attempted above is frag- mentary and dependent on the irregular distribution of the available evidence through time. It is not always possible to draw continuous his- torical lines. For example, the idea of social engineering, as reflected in cemetery organization under Sneferu and Khufu, is difficult to follow up in later dynasties. Either the phenomenon was short-lived or relevant patterns have not yet been detected in other cemeteries. However, the changing ways in which the relationship of the king to his courtiers and to the gods was articulated during the Old Kingdom demonstrate that kingship required explanation long before it became a theme of narrative literature in the Middle Kingdom. The dense written and visual discourse between courtiers is unique among evidence from Early Bronze Age societies and has provoked broader interpretive models in Egyptology. John Baines has remarked that visual display was more prestigious (and perhaps costlier) than hieroglyphic inscriptions were and for this reason was used exclusively for kings before it became more widely accessible to the courtiers. He called "decorum the implicit rules for what was considered appropriate for whom to display.s5 A major limitation he has credited to the rules of decorum is the absence of depictions of kings and deities in the tombs of the courtiers during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, although they are mentioned in inscriptions. The reasons are probably to be sought in changing regimes of accessibility but are otherwise difficult to identify. 7.3. Funerary culture and society Tombs provide the largest body of archaeological evidence for the Old Kingdom. They range from the pyramids of kings and queens to the mau- soleums of the courtiers and from the tombs of provincial governors and their dependents to pot burials and bodies interred without either a cof- fin or grave goods. The diversity of funerary arrangements sheds a light on social organization that is different from the elite-centered perspec- tives of courtly display and administrative documents. Human remains and burial equipment add aspects of body practices to the picture but generally tell us little about the profession or activities performed by the deceased during their lifetimes, although these were probably most rel- evant for delineating an individual's place in a social group. Tombs are also places where funerary rites were performed. The wealth of preserved evidencearchaeological, visual, and writtenraises hopes for under- standing the degree to which ritual practice can be understood to be an enactment of funerary beliefs