Your most important learning from Chapter 13 of the textbook:

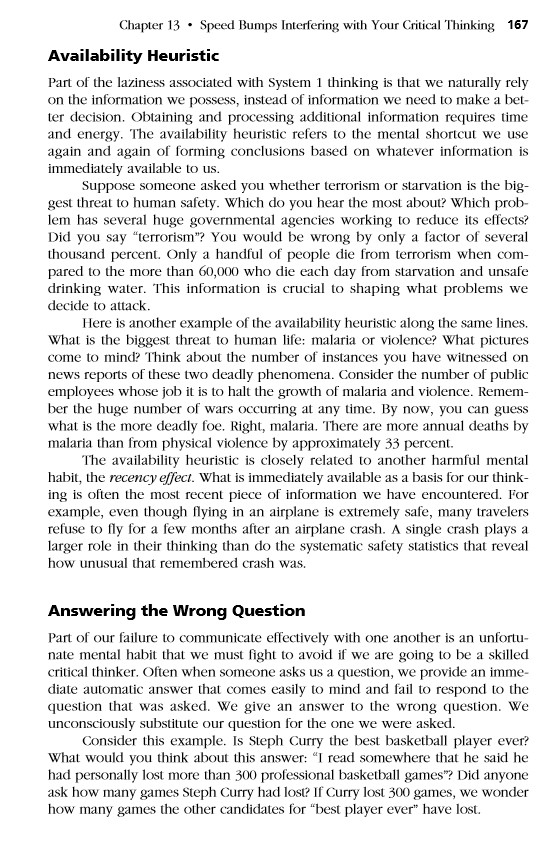

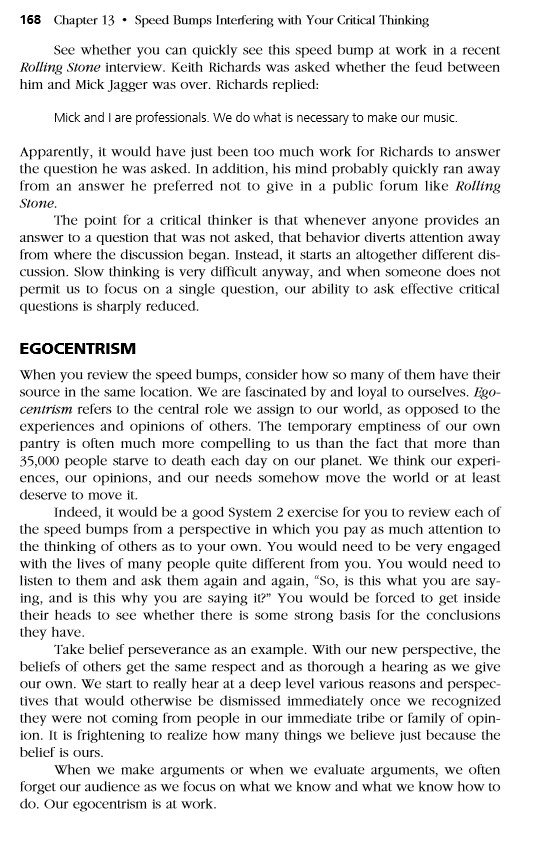

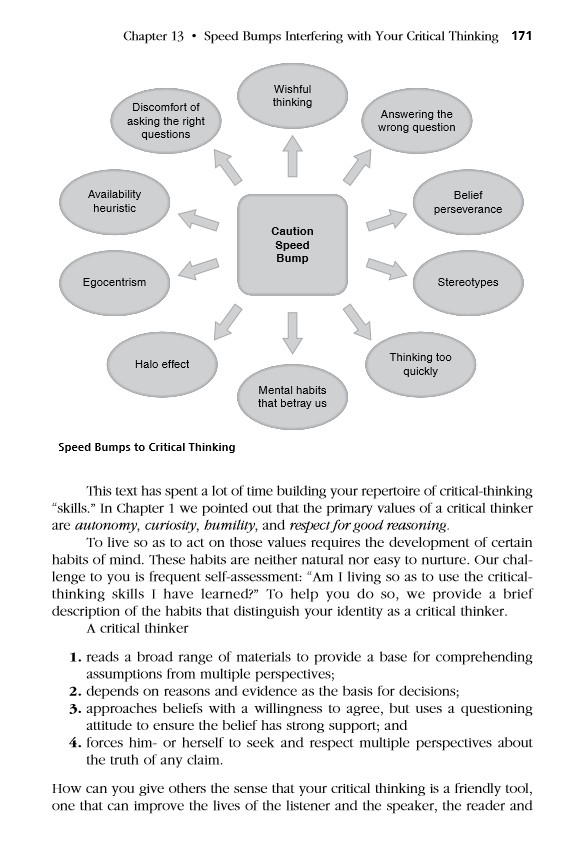

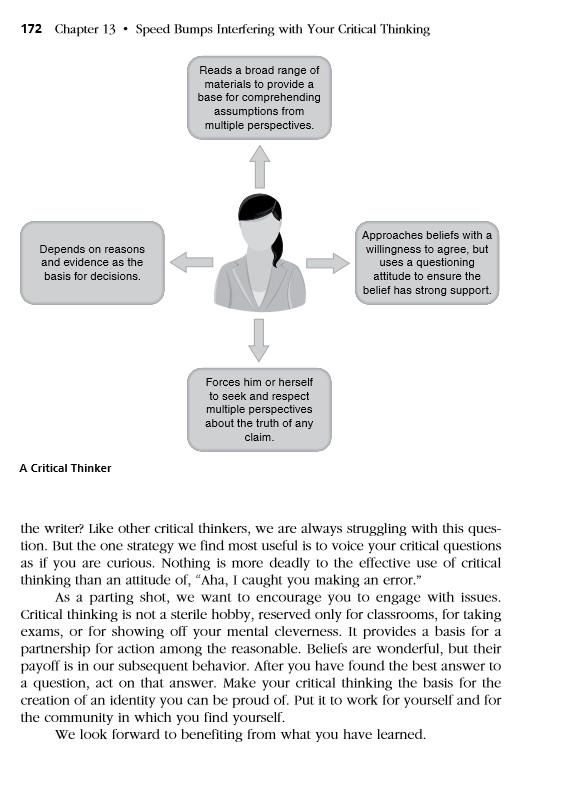

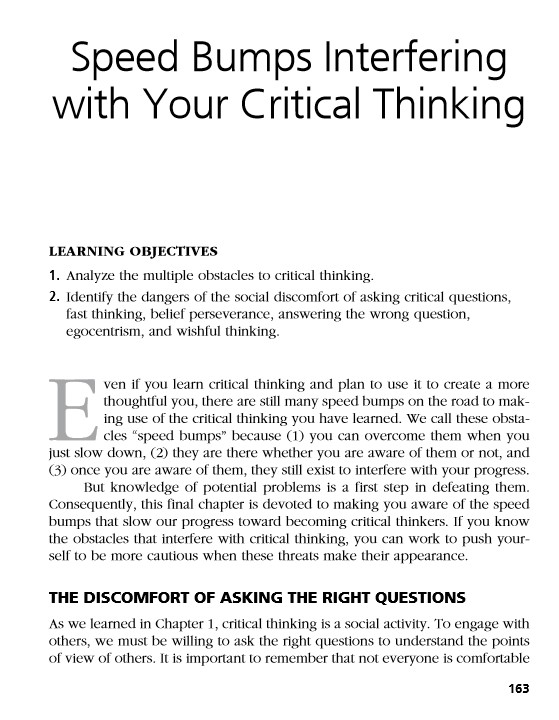

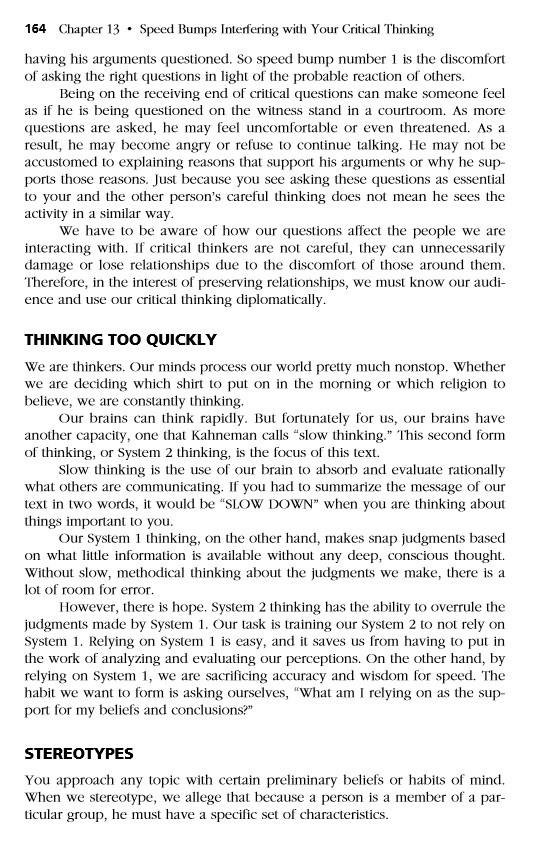

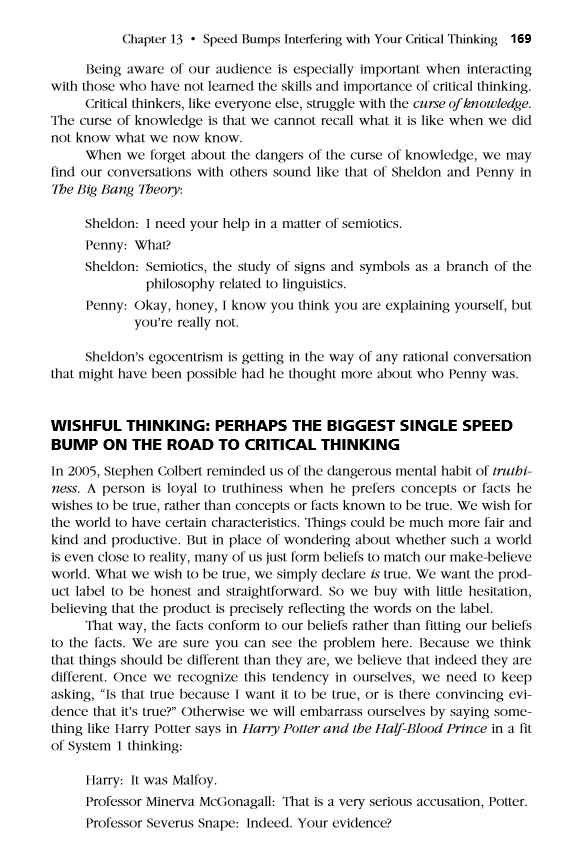

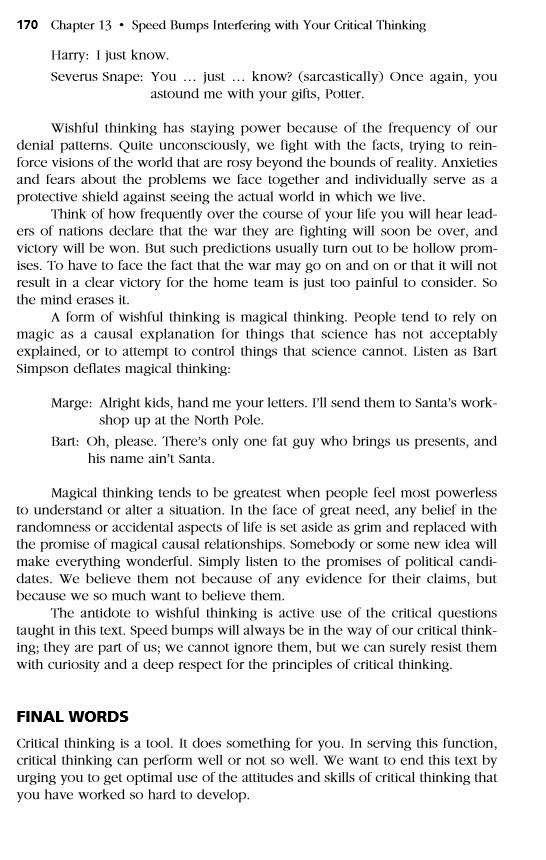

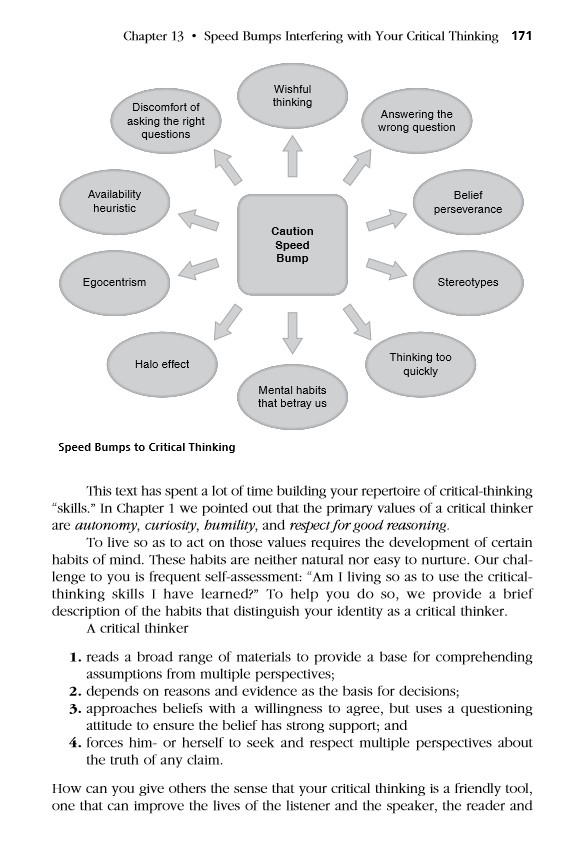

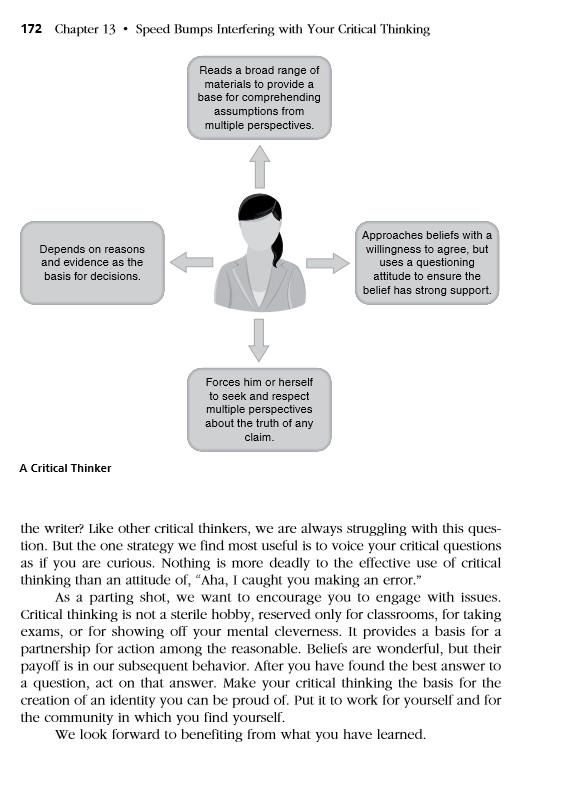

Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Analyze the multiple obstacles to critical thinking. 2. Identify the dangers of the social discomfort of asking critical questions, fast thinking, belief perseverance, answering the wrong question, egocentrism, and wishful thinking. E ven if you learn critical thinking and plan to use it to create a more thoughtful you, there are still many speed bumps on the road to mak- ing use of the critical thinking you have learned. We call these obsta- cles "speed bumps" because (1) you can overcome them when you just slow down, (2) they are there whether you are aware of them or not, and (3) once you are aware of them, they still exist to interfere with your progress. But knowledge of potential problems is a first step in defeating them. Consequently, this final chapter is devoted to making you aware of the speed bumps that slow our progress toward becoming critical thinkers. If you know the obstacles that interfere with critical thinking, you can work to push your- self to be more cautious when these threats make their appearance. THE DISCOMFORT OF ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS As we learned in Chapter 1, critical thinking is a social activity. To engage with others, we must be willing to ask the right questions to understand the points of view of others. It is important to remember that not everyone is comfortable 165 164 Chapter 13 Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking having his arguments questioned. So speed bump number 1 is the discomfort of asking the right questions in light of the probable reaction of others. Being on the receiving end of critical questions can make someone feel as if he is being questioned on the witness stand in a courtroom. As more questions are asked, he may feel uncomfortable or even threatened. As a result, he may become angry or refuse to continue talking. He may not be accustomed to explaining reasons that support his arguments or why he sup- ports those reasons. Just because you see asking these questions as essential to your and the other person's careful thinking does not mean he sees the activity in a similar way. We have to be aware of how our questions affect the people we are interacting with. If critical thinkers are not careful, they can unnecessarily damage or lose relationships due to the discomfort of those around them. Therefore, in the interest of preserving relationships, we must know our audi- ence and use our critical thinking diplomatically. THINKING TOO QUICKLY We are thinkers. Our minds process our world pretty much nonstop. Whether we are deciding which shirt to put on in the morning or which religion to believe, we are constantly thinking. Our brains can think rapidly. But fortunately for us, our brains have another capacity, one that Kahneman calls slow thinking." This second form of thinking, or System 2 thinking, is the focus of this text. Slow thinking is the use of our brain to absorb and evaluate rationally what others are communicating. If you had to summarize the message of our text in two words, it would be "SLOW DOWN" when you are thinking about things important to you. Our System 1 thinking, on the other hand, makes snap judgments based on what little information is available without any deep, conscious thought. Without slow, methodical thinking about the judgments we make, there is a lot of room for error. However, there is hope. System 2 thinking has the ability to overrule the judgments made by System 1. Our task is training our System 2 to not rely on System 1. Relying on System 1 is easy, and it saves us from having to put in the work of analyzing and evaluating our perceptions. On the other hand, by relying on System 1, we are sacrificing accuracy and wisdom for speed. The habit we want to form is asking ourselves, "What am I relying on as the sup- port for my beliefs and conclusions? STEREOTYPES You approach any topic with certain preliminary beliefs or habits of mind. When we stereotype, we allege that because a person is a member of a par- ticular group, he must have a specific set of characteristics. Chapter 13 Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking 165 Stereotypes are poor substitutes for slow thinking. Here are a few examples: 1. Men with facial hair are wise. 2. Overweight individuals are jolly. 3. Japanese are industrious. 4. Young people are frivolous. 5. Women make the best secretaries. 6. Welfare recipients are lazy. All six of these illustrations pretend to tell us something significant about the quality of certain types of people. If we believe these stereotypes, we will not approach people and their ideas with the spirit of openness necessary for strong-sense critical thinking. In addition, we will have an immediate bias toward any issue or controversy in which these people are involved. The ste- reotypes will have loaded the issue in advance, prior to the reasoning. Each person deserves our respect, and her arguments deserve our atten- tion. Stereotypes get in the way of critical thinking because they attempt to short circuit the difficult process of evaluation. As critical thinkers, we want to model curiosity and openness; stereotypes cut us off from careful consider- ation of what others are saying. They cause us to ignore valuable information by closing our minds prematurely. MENTAL HABITS THAT BETRAY US Our cognitive capabilities are numerous, but we are limited and betrayed by a series of mental habits. These cognitive biases push and pull us, unless we rope and tie them to make them behave. They move us in the direction of conclusions that we would never accept were we exercising the full range of critical thinking skills. While this section touches on only a few of them, understanding and trying to resist the ones we discuss will make a major con- tribution to the quality of your conclusions. Halo Effect The halo effect refers to our tendency to recognize one positive or negative quality or trait of a person, and then associate that quality or trait with every- thing about that person. The perceptions we have of people shape how we receive and evaluate their arguments. If someone is skilled in one aspect of her life, we place a halo on her in our minds. We assume that she must be skilled in other areas of her life. Consequently, we are overly open to her arguments. For example, a famous celebrity has an incredible singing voice and gives large amounts of money to charity. We are then surprised to learn that she is going to rehab for a drug addiction. We have over-exaggerated the 166 Chapter 13 . Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking goodness of the celebrity. Because of the halo effect, we have assumed that the celebrity is good in every aspect of her life, probably including even her thinking. Similarly, when someone does something we regard as awful, we think he is awful in all regards; we are closed off to his arguments. Even before we listen to a word such a person offers, we make a snap decision about whether that person is a good or bad person. Then we react to his opinions based on that fast thinking Belief Perseverance We enter all conversations with a huge amount of baggage. We have already had numerous experiences that have shaped us in some way; we each have dreams that guide what we see or hear; we each have cultural traditions that push us to think in certain ways. In short, you start with opinions. To return to the panning-for-gold metaphor, before you even dip your pan into the gravel you think you have gold in the pan. Your beliefs are valuable because they are yours. Understandably, you want to hold on to them. You have invested a lot of yourself in making those opinions part of who you are. This tendency for personal beliefs to stick or persevere is a major obsta- cle to critical thinking. We are biased from the start of an exchange in favor of our current opinions and conclusions. If I prefer the Democratic candidate for mayor, regardless of how shal- low my rationale is, I may resist your appeal on behalf of the Republican can- didate. I might feel bad about myself if I were to admit that my previous judgment had been flawed. This exaggerated loyalty to personal beliefs is one of the sources of confirmation bias, our tendency to see only that evidence that confirms what we already believe as being good evidence. In this man- ner, belief perseverance leads to weak-sense critical thinking. Part of what is going on with belief perseverance is our exaggerated sense of our own competence. We consistently tend to rate ourselves as more skilled at poker, grammar, and time management than any reasonable assess- ment would be able to find. This unfortunate habit of mind is probably respon- sible also for our sense that we are living in the midst of incredibly biased people, while we are unbiased. We tell ourselves that we see things as they are, while others look at the world through foggy, colored lens. Our biggest bias may be that we are not biased, but those with whom we disagree are! To counter belief perseverance, it's helpful to remember that strong- sense critical thinking requires the recognition that judgments are tentative or contextual. We can never permit ourselves to be so sure of anything that we stop searching for an improved version. As the famous scientist Francis Bacon pointed out in 1620, when we change our minds in light of a superior argu- ment, we deserve to be proud that we have resisted the temptation to remain true to long-held beliefs. Such a change of mind deserves to be seen as reflecting a rare strength. Chapter 13 Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking 167 Availability Heuristic Part of the laziness associated with System 1 thinking is that we naturally rely on the information we possess, instead of information we need to make a bet- ter decision. Obtaining and processing additional information requires time and energy. The availability heuristic refers to the mental shortcut we use again and again of forming conclusions based on whatever information is immediately available to us. Suppose someone asked you whether terrorism or starvation is the big- gest threat to human safety. Which do you hear the most about? Which prob- lem has several huge governmental agencies working to reduce its effects? Did you say "terrorism"? You would be wrong by only a factor of several thousand percent. Only a handful of people die from terrorism when com- pared to the more than 60,000 who die each day from starvation and unsafe drinking water. This information is crucial to shaping what problems we decide to attack Here is another example of the availability heuristic along the same lines. What is the biggest threat to human life: malaria or violence? What pictures come to mind? Think about the number of instances you have witnessed on news reports of these two deadly phenomena. Consider the number of public employees whose job it is to halt the growth of malaria and violence. Remem- ber the huge number of wars occurring at any time. By now, you can guess what is the more deadly foe. Right, malaria. There are more annual deaths by malaria than from physical violence by approximately 33 percent. The availability heuristic is closely related to another harmful mental habit, the recency effect. What is immediately available as a basis for our think- ing is often the most recent piece of information we have encountered. For example, even though flying in an airplane is extremely safe, many travelers refuse to fly for a few months after an airplane crash. A single crash plays a larger role in their thinking than do the systematic safety statistics that reveal how unusual that remembered crash was. Answering the Wrong Question Part of our failure to communicate effectively with one another is an unfortu- nate mental habit that we must fight to avoid if we are going to be a skilled critical thinker. Often when someone asks us a question, we provide an imme- diate automatic answer that comes easily to mind and fail to respond to the question that was asked. We give an answer to the wrong question. We unconsciously substitute our question for the one we were asked. Consider this example. Is Steph Curry the best basketball player ever? What would you think about this answer: "I read somewhere that he said he had personally lost more than 300 professional basketball games? Did anyone ask how many games Steph Curry had lost? If Curry lost 300 games, we wonder how many games the other candidates for "best player ever" have lost. 168 Chapter 13 . Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking See whether you can quickly see this speed bump at work in a recent Rolling Stone interview. Keith Richards was asked whether the feud between him and Mick Jagger was over. Richards replied: Mick and I are professionals. We do what is necessary to make our music. Apparently, it would have just been too much work for Richards to answer the question he was asked. In addition, his mind probably quickly ran away from an answer he preferred not to give in a public forum like Rolling Stone, The point for a critical thinker is that whenever anyone provides an answer to a question that was not asked, that behavior diverts attention away from where the discussion began. Instead, it starts an altogether different dis- cussion. Slow thinking is very difficult anyway, and when someone does not permit us to focus on a single question, our ability to ask effective critical questions is sharply reduced. EGOCENTRISM When you review the speed bumps, consider how so many of them have their source in the same location. We are fascinated by and loyal to ourselves. Ego- centrism refers to the central role we assign to our world, as opposed to the experiences and opinions of others. The temporary emptiness of our own pantry is often much more compelling to us than the fact that more than 35,000 people starve to death each day on our planet. We think our experi- ences, our opinions, and our needs somehow move the world or at least deserve to move it Indeed, it would be a good System 2 exercise for you to review each of the speed bumps from a perspective in which you pay as much attention to the thinking of others as to your own. You would need to be very engaged with the lives of many people quite different from you. You would need to listen to them and ask them again and again, So, is this what you are say- ing, and is this why you are saying it?" You would be forced to get inside their heads to see whether there is some strong basis for the conclusions they have Take belief perseverance as an example. With our new perspective, the beliefs of others get the same respect and as thorough a hearing as we give our own. We start to really hear at a deep level various reasons and perspec- tives that would otherwise be dismissed immediately once we recognized they were not coming from people in our immediate tribe or family of opin- ion. It is frightening to realize how many things we believe just because the belief is ours. When we make arguments or when we evaluate arguments, we often forget our audience as we focus on what we know and what we know how to do. Our egocentrism is at work. Chapter 13 Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking 169 Being aware of our audience is especially important when interacting with those who have not learned the skills and importance of critical thinking. Critical thinkers, like everyone else, struggle with the curse of knowledge. The curse of knowledge is that we cannot recall what it is like when we did not know what we now know. When we forget about the dangers of the curse of knowledge, we may find our conversations with others sound like that of Sheldon and Penny in The Big Bang Theory: Sheldon: I need your help in a matter of semiotics. Penny: What? Sheldon: Semiotics, the study of signs and symbols as a branch of the philosophy related to linguistics. Penny: Okay, honey, I know you think you are explaining yourself, but you're really not. Sheldon's egocentrism is getting in the way of any rational conversation that might have been possible had he thought more about who Penny was. WISHFUL THINKING: PERHAPS THE BIGGEST SINGLE SPEED BUMP ON THE ROAD TO CRITICAL THINKING In 2005, Stephen Colbert reminded us of the dangerous mental habit of truthi- ness. A person is loyal to truthiness when he prefers concepts or facts he wishes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true. We wish for the world to have certain characteristics. Things could be much more fair and kind and productive. But in place of wondering about whether such a world is even close to reality, many of us just form beliefs to match our make-believe world. What we wish to be true, we simply declare is true. We want the prod- uct label to be honest and straightforward. So we buy with little hesitation, believing that the product is precisely reflecting the words on the label. That way, the facts conform to our beliefs rather than fitting our beliefs to the facts. We are sure you can see the problem here. Because we think that things should be different than they are, we believe that indeed they are different. Once we recognize this tendency in ourselves, we need to keep asking, "Is that true because I want it to be true, or is there convincing evi- dence that it's true?" Otherwise we will embarrass ourselves by saying some- thing like Harry Potter says in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince in a fit of System 1 thinking: Harry: It was Malfoy. Professor Minerva McGonagall: That is a very serious accusation, Potter. Professor Severus Snape: Indeed. Your evidence? 170 Chapter 13 . Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking Harry: I just know. Severus Snape: You ... just ... know? (sarcastically) Once again, you astound me with your gifts, Potter. Wishful thinking has staying power because of the frequency of our denial patterns. Quite unconsciously, we fight with the facts, trying to rein- force visions of the world that are rosy beyond the bounds of reality. Anxieties and fears about the problems we face together and individually serve as a protective shield against seeing the actual world in which we live. Think of how frequently over the course of your life you will hear lead- ers of nations declare that the war they are fighting will soon be over, and victory will be won. But such predictions usually turn out to be hollow prom- ises. To have to face the fact that the war may go on and on or that it will not result in a clear victory for the home team is just too painful to consider. So the mind erases it. A form of wishful thinking is magical thinking. People tend to rely on magic as a causal explanation for things that science has not acceptably explained, or to attempt to control things that science cannot. Listen as Bart Simpson deflates magical thinking: Marge: Alright kids, hand me your letters. I'll send them to Santa's work- shop up at the North Pole. Bart: Oh, please. There's only one fat guy who brings us presents, and his name ain't Santa. Magical thinking tends to be greatest when people feel most powerless to understand or alter a situation. In the face of great need, any belief in the randomness or accidental aspects of life is set aside as grim and replaced with the promise of magical causal relationships. Somebody or some new idea will make everything wonderful. Simply listen to the promises of political candi- dates. We believe them not because of any evidence for their claims, but because we so much want to believe them. The antidote to wishful thinking is active use of the critical questions taught in this text. Speed bumps will always be in the way of our critical think- ing; they are part of us; we cannot ignore them, but we can surely resist them with curiosity and a deep respect for the principles of critical thinking. FINAL WORDS Critical thinking is a tool. It does something for you. In serving this function, critical thinking can perform well or not so well. We want to end this text by urging you to get optimal use of the attitudes and skills of critical thinking that you have worked so hard to develop. Chapter 13 . Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking 171 Wishful thinking Discomfort of asking the right questions Answering the wrong question Availability heuristic Belief perseverance Caution Speed Bump Egocentrism Stereotypes Halo effect Thinking too quickly Mental habits that betray us Speed Bumps to Critical Thinking This text has spent a lot of time building your repertoire of critical thinking "skills." In Chapter 1 we pointed out that the primary values of a critical thinker are autonomy, curiosity, humility, and respect for good reasoning. To live so as to act on those values requires the development of certain habits of mind. These habits are neither natural nor easy to nurture. Our chal- lenge to you is frequent self-assessment: "Am I living so as to use the critical- thinking skills I have learned?" To help you do so, we provide a brief description of the habits that distinguish your identity as a critical thinker. A critical thinker 1. reads a broad range of materials to provide a base for comprehending assumptions from multiple perspectives; 2. depends on reasons and evidence as the basis for decisions; 3. approaches beliefs with a willingness to agree, but uses a questioning attitude to ensure the belief has strong support; and 4. forces him or herself to seek and respect multiple perspectives about the truth of any claim. How can you give others the sense that your critical thinking is a friendly tool, one that can improve the lives of the listener and the speaker, the reader and 172 Chapter 13 - Speed Bumps Interfering with Your Critical Thinking Reads a broad range of materials to provide a base for comprehending assumptions from multiple perspectives. Depends on reasons and evidence as the basis for decisions. Approaches beliefs with a willingness to agree, but uses a questioning attitude to ensure the belief has strong support. Forces him or herself to seek and respect multiple perspectives about the truth of any claim. A Critical Thinker the writer? Like other critical thinkers, we are always struggling with this ques- tion. But the one strategy we find most useful is to voice your critical questions as if you are curious. Nothing is more deadly to the effective use of critical thinking than an attitude of, "Aha, I caught you making an error." As a parting shot, we want to encourage you to engage with issues. Critical thinking is not a sterile hobby, reserved only for classrooms, for taking exams, or for showing off your mental cleverness. It provides a basis for a partnership for action among the reasonable. Beliefs are wonderful, but their payoff is in our subsequent behavior. After you have found the best answer to a question, act on that answer. Make your critical thinking the basis for the creation of an identity you can be proud of. Put it to work for yourself and for the community in which you find yourself. We look forward to benefiting from what you have learned