Question: Create a list you may use in class, with others and solo explain? 10 Culturally Inclusive Instruction Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should

Create a list you may use in class, with others and solo explain?

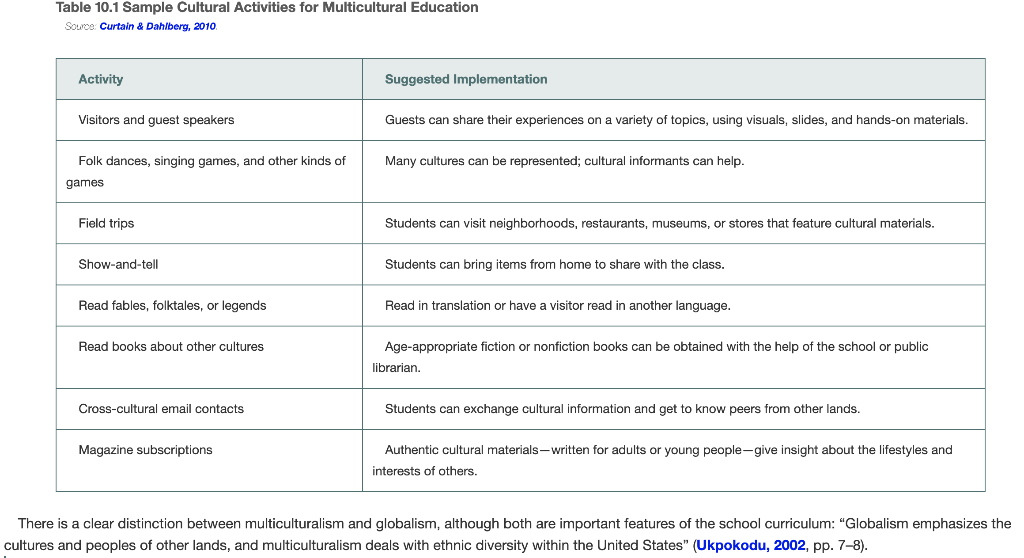

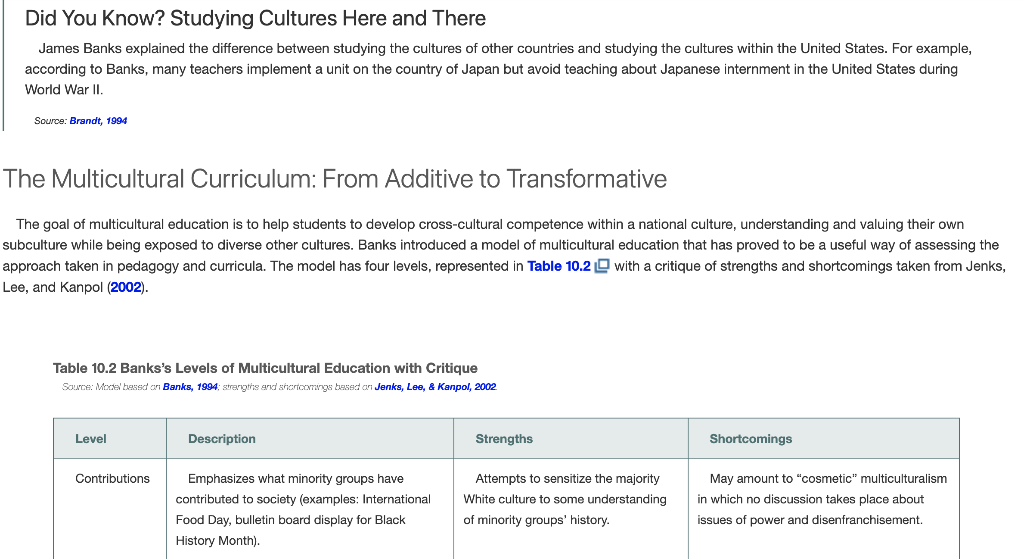

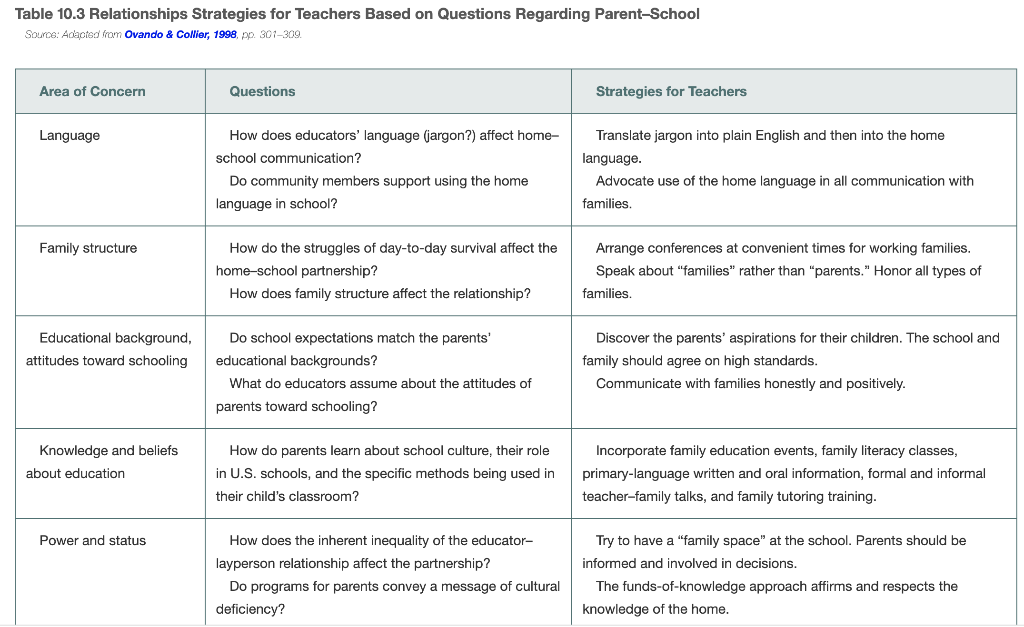

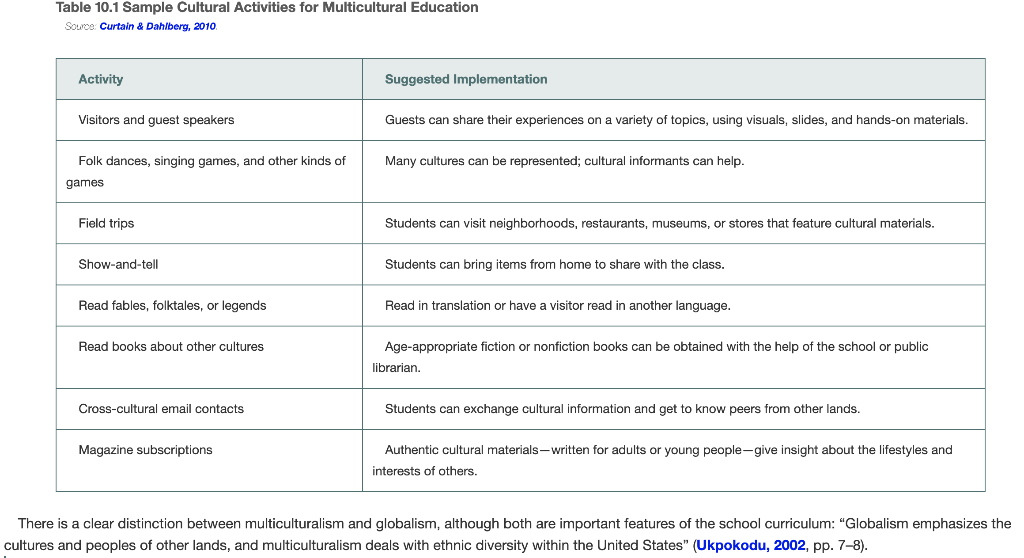

10 Culturally Inclusive Instruction Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able to ... Explain the role that culture plays in the classroom and school, including ways that teachers can honor students' diversity, make meaningful connections between home and school, help students to accommodate to the cultural of school without loss of their cultural uniqueness, and adapt to ways that students' culture can help or hinder their school success; Identify ways that students can learn about multicultural diversity, validate their own cultural identities, and respect the cultures of others; Explore students' cultures using ethnography as well as seeking information from students themselves, their families and communities, and Internet resources; Describe what makes a classroom culturally inclusive; and Acquire the disposition to involve schools and families in meaningful partnerships. The Role of Culture in the Classroom and School Culture influences every aspect of school life. Becoming an intercultural educator requires not only specific knowledge about the culture(s) of the students but also general knowledge about how to use that knowledge appropriately in specific contexts. Students from a nonmainstream culture are acquiring a mainstream classroom culture that may differ markedly from their home culture. Intercultural educators who understand students' cultures can then design instruction to meet children's learning needs. Acknowledging Students' Differences Imagine a classroom of thirty students, each with just one unique fact, value, or belief included in the more than fifty categories presented in Table 9.2 ("Components of Culture"). Yet this dizzying array of uniqueness is only the tip of the iceberg, because within each of these categories individuals can still differ. Take, for example, the category "food" under "daily life" in Table 9.2. Each student in a classroom of thirty knows a lot about food. What they know, however, depends largely on what they eat every day. Culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students offer educators a rich opportunity for learning about the varieties of values and behaviors that characterize human nature. Culture includes diversity in values, social customs, rituals, work and leisure activities, health and educational practices, and many other aspects of life. Each of these can affect schooling, as we will discuss, including ways that teachers can respond to these differences in adapting instruction. The Alignment of Home and School Teachers who are members of the mainstream culture and have an accommodating vision of cultural diversity recognize that they need to adapt culturally to CLD students, just as these individuals, in turn, accept some cultural change as they adapt to the mainstream. In this mutual process, teachers who model receptiveness to learning from the diverse cultures in their midst help students to see this diversity as a resource. All the influences that contribute to the cultural profile of the family and community affect the students' reactions to classroom practices. Students whose home culture is consistent with the beliefs and practices of the school are generally more successful in school. However, different cultures organize individual and community behavior in radically different ways-ways that, on the surface, may not seem compatible with school practices and beliefs. To understand these differences is to be able to mediate for the students by helping them bridge relevant differences between the home and the school cultures. Cultural accommodation is a two-way exchange. Obviously, a single teacher cannot change the culture of an entire school; similarly, families cannot change the deep structure of their values solely for the sake of their children's school success. Flexibility and awareness of cultural differences go a long way toward supporting students and defusing misunderstanding. The Value System of the Teacher and Cultural Accommodation Because culture plays such an important role in the classroom and the school, the degree to which home and school are congruent can affect the student's learning and achievement. Some of this congruence-the facilitative alignment of the cultures of home and school-depends on what teachers see as important. Because more than 80 percent of teachers represent mainstream culture, the following information contrasts U.S. mainstream values with those that might differ. What Are Values? Values are "beliefs about how one ought or ought not to behave or about some end state of existence worth or not worth attaining" (Bennett, 2003, p. 64). Values are particularly important to people when they educate their young, because education is a primary means of transmitting cultural knowledge. Parents in minority communities are often vitally interested in their children's education even though they may not be highly visible at school functions. Values about Time Cultures cause people to lead very different daily lives. These customs are paced and structured by deep habits of using time and space. For example, time is organized in culturally specific ways. Classroom Glimpse Cultural Values About Time Adela, a Mexican American first-grader, arrived at school about twenty minutes late every day. Her teacher was at first irritated and gradually exasperated. In a parent conference, Adela's mother explained that braiding her daughter's hair each morning was an important time for the two of them to be together, even if it meant being slightly late to school. This family time presented a values conflict with the school's time norms. Other conflicts may arise when teachers demand abrupt endings to activities in which children are deeply engaged or when events are scheduled in a strict sequence. In fact, schools in the United States are often paced very strictly by clock time, whereas family life in various cultures is not regulated in the same manner. Moreover, teachers often equate speed of performance with intelligence, and standardized tests are often a test of rapidity. Many teachers find themselves in the role of "time mediator"-helping the class adhere to the school's time schedule while working with individual students to help them meet their learning needs within the time allotted. Best Practice Accommodating to Different Concepts of Time and Work Rhythms Provide students with choices about their work time and observe how time spent on various subjects accords with students' aptitudes and interests. If a student is a slow worker, analyze the work rhythms. Slow yet methodically accurate work deserves respect, but slow and disorganized work may require a peer helper. If students are chronically late to school, ask the counselor to meet with the responsible family member to discuss a change in morning routines. Values about Space The concept and experience of space is another aspect about which values differ according to cultural experience. Just as attitudes toward personal space vary among cultures, a cultural sense of space influences in which rooms and buildings people feel comfortable. Large cavernous classrooms may be overwhelming to students whose family activities are carried out in intimate spaces. The organization of the space in the classroom sends messages to students, such as how free they are to move about the classroom and how much of the classroom they "own." Both the expectations of the students and the needs of the teacher can be negotiated to provide a classroom setting in which space is shared. Classroom Glimpse The Textbooks' "Hidden Messages" about Space Joe Suina discusses the way school textbooks enticed young Native American children to devalue their heritage: Messages are ever so subtle, yet very powerful. The textbooks I had as a child, for example, that pictured only pitched roofs and straight walls, sidewalks and grass. My world was quite different; it was one of adobe homes, dirt ficors, the bare ground, and not a whole lot of vegetation in the yard that I was growing up in. It was a different way of life, a different lifestyle that was presented clearly as one to be valued over anything else. But because these materials were produced by very educated people, in high gloss, and in the context of being central to the curriculum, they communicated very strongly "the ideal life." As if to say, "This was what you become and get when you get educated, when you finally get civilized! What you have at home now is not good enough!" (Suina, 2011, n.p.) Values about Dress and Appearance Sometimes values are about externals, such as dress and personal appearance. For example, a third-grade girl wearing makeup is communicating a message that some teachers may consider an inappropriate indicator of premature sexuality, although makeup on a young girl may be acceptable in some cultures. Best Practice Culturally Influenced School Dress Codes . Boys and men in some cultures (rural Mexico, for example) wear hats. Classrooms need to have a place for these hats during class time and provision for wearing the hats during recess. Schools that forbid "gang attire" yet permit privileged students to wear such regalia as high school sororities (sweaters with embroidered names, for instance) should forbid clique-related attire for all. A family-school council with representatives from various cultures should be responsible for reviewing the school dress code on a yearly basis to see if it meets the needs of various cultures. Rites, Rituals, and Ceremonies Each culture incorporates expectations about the proper means for carrying out formal events. School ceremonies-for example, assemblies that begin with formal markers such as the Pledge of Allegiance and a flag salute-should have nonstigmatizing alternatives for those whose culture does not permit participation. Rituals in some elementary classrooms in the United States are relatively informal. For example, students can enter freely before school and take their seats or go to a reading corner or activity center. Students from other cultures may find this confusing if they are accustomed to lining up in the courtyard, being formally greeted by the principal or head teacher, and then invited in their lines to enter their respective classrooms. A traditional Hawaiian custom involved students chanting outside the classroom door and listening for the teacher's welcome chant from within. In U.S. classrooms, a bell normally rings to start the school day, but individual class periods at the elementary level are not usually set off by formal signals to cue transitions. Best Practice Accommodating School Rituals Teachers might welcome newcomers with a brief explanation of the degree of formality expected of students. School seasonal celebrations are increasingly devoid of political and religious content. The school may, however, permit school clubs to honor events with extracurricular rituals. Teachers might observe colleagues from different cultures to view the rituals of family-teacher conferences and adapt their behavior accordingly to address families' cultural expectations. Greeting and welcome behaviors during parent conferences vary across cultures. The sensitive teacher understands how parents expect to be greeted and incorporates some of these behaviors in the exchange. Values about Work and Leisure Cross-cultural variation in work and leisure activities is a frequently discussed value difference. Many members of mainstream U.S. culture value work over play; that is, one's status is directly related to one's productivity, salary, or job description. Play, rather than being an end in itself, is often used in ways that reinforce the status achieved through work. For example, teachers may meet informally at someone's home to bake holiday dishes, coworkers form bowling leagues, and alumni enjoy tailgate parties before attending football games; one's work status often governs who is invited to attend these events. Young people in the mainstream U.S. culture, particularly those in the middle class, are trained to use specific tools of play, and their time is structured to attain skills (e.g., organized sports, music lessons). In contrast, other cultures do not afford children structured time to play but instead expect children to engage in adult- type labor at work or in the home. In still other cultures, such as that of the Hopi Nation in Arizona, children's playtime is relatively unstructured, and parents do not interfere with play. Cultures also vary in the typical work and play activities expected of girls and of boys. All these values have obvious influence on the ways children work and play at school. In work and play groups, the orientation may be individual or group. The United States is widely regarded as a society in which the individual is paramount. This individualism often pits students against one another for achievement. In contrast, many Mexican immigrants from rural communities have group-oriented values and put the needs of the community before individual achievement. Families may, for example, routinely pull children from school to attend funerals of neighbors in the community; in mainstream U.S. society, however, children would miss school only for the funerals of close family members. Best Practice Accommodating Diverse Ideas about Work and Play Many high school students arrange class schedules to work part time. If a student appears chronically tired, a family-teacher conference may be needed to review priorities. Many students are overcommitted to extracurricular activities. If grades suffer, students may be well advised to reduce activities to regain an academic focus. Out-of-school play activities should not be organized at the school site, such as passing out birthday party invitations that exclude some students. Values about Medicine, Health, and Hygiene Health and medicine practices involve deep-seated beliefs because the stakes are high: life and death. Each culture has certain beliefs about sickness and health, beliefs that influence the interactions in health care settings. Students may have problems-war trauma, culture shock, poverty, addiction, family violence, crime that their culture treats in particular culturally acceptable ways. When students come to school with health issues, teachers need to react in culturally compatible ways. Miscommunication and noncooperation can result when teachers and the family view health and disease differently. For example, community health practices, such as the Cambodian tradition of coining (in which a coin is dipped in oil and then rubbed on a sick person's back, chest, and neck), can be misinterpreted by school officials who, seeing marks on the child, might call Child Protective Services. Classroom Glimpse Exotic Family Health Practice? One of Ka's uncles called to explain that his nephew was sick and would miss school another two days. Lenny had read that the Hmong were animists and believed sickness was often caused by evil spirits who lured the soul from the body. Getting well sometimes required an animal sacrifice and a healing ceremony with a shaman who found and returned the runaway soul. Lenny wished the boy well and then asked about the nature and course of Ka's treatment, fully expecting evil spirit, animal sacrifice, and shaman scenarios. "Strep throat," answered the uncle, "but we went to the hospital and got antibiotics." Source: Cary, 2000, p. 19 Best Practice Health and Hygiene Practices Families who send sick children to school or, conversely, keep children home at the slightest ache may benefit from a conference with the school nurse. All students can profit from explicit instruction in home and school hygiene. Values about Economics, Law, Politics, and Religion The institutions that support and govern family and community life have an influence on behavior and beliefs. The economic institutions of the United States are diverse, ranging from small business enterprises to large corporate or government agencies. These institutions influence daily life in the United States by means of a complex infrastructure. The families of English learners may fit in anywhere along this continuum. Classroom Glimpse Exotic Family Health Practice? One of Ka's uncles called to explain that his nephew was sick and would miss school another two days. Lenny had read that the Hmong were animists and believed sickness was often caused by evil spirits who lured the soul from the body. Getting well sometimes required an animal sacrifice and a healing ceremony with a shaman who found and returned the runaway soul. Lenny wished the boy well and then asked about the nature and course of Ka's treatment, fully expecting evil spirit, animal sacrifice, and shaman scenarios. "Strep throat," answered the uncle, "but we went to the hospital and got antibiotics." Source: Cary, 2000, p. 19 Best Practice Health and Hygiene Practices Families who send sick children to school or, conversely, keep children home at the slightest ache may benefit from a conference with the school nurse. All students can profit from explicit instruction in home and school hygiene. Values about Economics, Law, Politics, and Religion The institutions that support and govern family and community life have an influence on behavior and beliefs. The economic institutions of the United States are diverse, ranging from small business enterprises to large corporate or government agencies. These institutions influence daily life in the United States by means of a complex infrastructure. The families of English learners may fit in anywhere along this continuum. Interwoven into this rich cultural-economic-political-legal texture are religious beliefs and practices. In the United States, religious practices are heavily embedded but formally bounded-people argue over Christmas trees in public schools but there is almost universal acceptance of increased consumer spending at the close of the calendar year. Religious beliefs underlie other cultures even more fundamentally. Followers of Islam, for example, are accustomed to overt prayer, and may seek to respond publicly to the call to prayer. This contrasts to mainstream U.S. religious beliefs that prayer is a private (non-public) matter. Some schools respond by providing nondenominational "quiet" rooms to accommodate the periodic need for prayer. In Islamic traditions, the Koran prescribes proper social relationships and roles for members of society. Immigrants with Confucian religious and philosophical beliefs subscribe to values that mandate a highly ordered society and family through the maintenance of proper social relationships. When immigrants with these religious beliefs encounter the largely secular U.S. institutions, the result may be that customs and cultural patterns are challenged, fade away, or cause conflict within the family (Chung, 1989). Best Practice Accommodating Economic, Legal, Political, and Religious Practices On a rotating basis, teachers could be paid to supervise after-school homework sessions for students whose parents are working multiple jobs. Schools can legally resist any attempts to identify families whose immigration status is undocumented. Schools should not tolerate messages of political partisanship. Permission for religious garb or appearance (e.g., Islamic head scarves, Sikh ritual knives, Hassidic dress) should be a part of the school dress code. Values and Expectations about Education In the past, educational systems were designed to pass on cultural knowledge and traditions, which constituted much the same learning that parents taught their children. Students come to school steeped in the learning practices of their own family and community. However, many of the organizational and teaching practices of the school may not support the type of learning to which students are accustomed. For example, Indochinese students expect to listen, watch, and imitate. They may be reluctant to ask questions or volunteer answers and may be embarrassed to ask for the teacher's help or reluctant to participate in individual demonstrations of a skill or project. For immigrant children with previous schooling, experience in U.S. classrooms may engender severe conflicts. Teachers who can accommodate these students' proclivities can gradually introduce student-centered practices while supporting an initial dependence on the teacher's direction. Did You Know? Overcoming Passivity Polynesian students newly arrived from the South Pacific may have experienced classroom learning as a relatively passive activity. They expect teachers to give explicit instruction about what to learn and how to learn it. When these students arrive in the United States and encounter teachers who value creativity and student-centered learning, they may appear passive as they wait to be told what to do. Source: Funaki & Burnett, 1993 Best Practice Accommodating Culturally Based Educational Expectations Teachers who seek to understand the value of education within the community can do the following: Invite classroom guests from the community to share methods for teaching and learning that are used in the home (e.g., modeling and imitation, didactic stories and proverbs, direct verbal instruction). Pair children from cultures that expect passive responses to teachers (observing only) with more participatory peers to help the former learn to ask questions and volunteer. In communities with a high dropout rate, support the systematic efforts of school counselors and administrators to help families accommodate their beliefs to a more proactive support for school completion and higher education. Values about Roles and Status Cultures differ in the roles people play in society and the status accorded to these roles. For example, in the Vietnamese culture, profoundly influenced by Confucianism, authority figures are ranked in the following manner: The father ranks below the teacher, who ranks only below the king. Such a high status is not accorded to teachers in U.S. society, where, instead, medical doctors enjoy this type of prestige. Such factors as gender, social class, age, occupation, and education level influence the manner in which status is accorded to various roles. Students' perceptions about the roles possible for them in their culture affect their school performance. Values about Gender In many cultures, gender is related to social roles in a similar way. Anthropologists have found men to be in control of political and military matters in all known cultures. Young boys tend to be more physically and verbally aggressive and to seek dominance more than girls do. Traditionally, women have had the primary responsibility for child-rearing, with associated tasks, manners, and responsibilities. Immigrants to the United States often come from cultures in which men and women have rigid and highly differentiated gender roles. The gender equality that is an ostensible goal in U.S. classrooms may be difficult for students of these cultures. Classroom Glimpse To Mentor or Not to Mentor? Chad is a journalism teacher in a large urban high school and the advisor of the school newspaper. Khalia is a young woman who enrolled in a beginning journalism class as a junior. Although English was not her first language, she showed unusual ability and creativity in writing the stories to which she was assigned. Chad routinely advises students on their vocational choice, writes letters of recommendation for them when they apply to college, and encourages those who want to further their education. Khalia has confided in him that her parents have discouraged her from attending college. Khalia does not want to marry immediately after high school and has asked Chad's help in applying to college. Should Chad help Khalia? Best Practice Gender-Role Expectations Monitor tasks assigned to boys and girls to ensure they are the same. Make sure that boys and girls perform equal leadership roles in cooperative groups. . If families in a given community provide little support for the scholastic achievement of girls, a systematic effort on the part of school counselors and administrators may be needed to help families accommodate their beliefs to a more proactive support for women. Values about Social Class Stratification by social class differs across cultures. Cultures that are rigidly stratified, such as India's caste system, differ from cultures that are not as rigid or that, in some cases, border on the anarchic, such as continuously war-torn countries. The belief that education can enhance economic status is widespread in the dominant culture of the United States, but individuals in other cultures may not have similar beliefs. In general, individuals and families at the upper socioeconomic levels are able to exert power by sitting on college, university, and local school boards and thus determining who receives benefits and rewards through schooling. However, middle-class values are those that are generally incorporated in the culture of schooling. The social-class values that children learn in their homes largely influence not only their belief in schooling but also their routines and habits in the classroom. Best Practice Accommodating the Influence of Social Class on Schooling Students who are extremely poor or homeless may need help from the teacher to store possessions at school. . A teacher who receives an expensive gift should consult the school district's ethics policies. The successful outcome of a school assignment or project should not depend on extensive family financial resources. Values about Age-Appropriate Activities Age interacts with culture, socioeconomic status, gender, and other factors to influence an individual's behavior and attitudes. In various cultures, expectations about appropriate activities for children and the purpose of those activities differ. Middle-class European Americans expect children to spend much of their time playing and attending school rather than performing tasks similar to those of adults; some families, however, expect their children to take sports activities as seriously as do professional athletes. Cree Indian children, on the other hand, are expected from an early age to learn adult roles, including contributing food to the family. Parents may criticize schools for involving children in tasks that are not related to their future participation in Cree society (Sindell, 1988). Cultures also differ in their criteria for moving through the various (culturally defined) life cycle changes. An important stage in any culture is the move into adulthood, but the age at which this occurs and the criteria necessary for attaining adulthood vary according to what adulthood means in a particular culture. Rural, traditional families in many countries expect young men and women to be socially mature when they enter high school, whereas other families, for example, middle-class families in Taiwan, expect a much longer period of adolescence. Best Practice Accommodating Diverse Ideas about Work and Play Child labor laws in the United States forbid students from working for pay before a given age. However, few laws govern children working in family businesses. If a child appears chronically tired, the school counselor may need to discuss the child's involvement in a family business with a responsible family member. Cultural groups which girls are expected to marry and have children at the age of fifteen or sixteen (e.g., Hmong) may need access to alternative schools. . If a student misses school because of obligations to accompany family members to social services to act as a translator or to stay at home as a babysitter, the school counselor may be able to intervene to help families find other resources. Values about Occupations In the United States, occupation very often determines income, which in turn is a chief determinant of prestige in the culture. Other cultures, however, may attribute prestige to those with inherited status or to those who have a religious function in the culture. Prestige is one factor in occupational choices. Other factors can include cultural acceptance of the occupation, educational requirements, gender, and attainability. Students therefore may not see all occupations as desirable or even available to them and may have mixed views about the role education plays in their future occupations. Some cultural groups in the United States are engaged in a voluntary way of life that does not require public schooling (e.g., the Amish). Other groups may not be adequately rewarded in the United States for school success but expect to be rewarded elsewhere (e.g., children of diplomats and short-term residents who expect to return to their home country). Still other groups may be involuntarily incorporated into U.S. society and relegated to menial occupations and ways of life that do not reward and require school success. As a result, they may not apply academic effort (Ogbu & Matute-Bianchi, 1986). Best Practice Accommodating Occupational Aspirations At all grade levels, school subjects should be connected with future vocations. Role models from minority communities might be invited to visit the classroom to recount stories of their success. Successful professionals and businesspeople can visit and explain how cultural diversity is supported in their place of work. Teachers should make available at every grade an extensive set of books on occupations and their requirements and discuss these with students. Values about Child-Rearing The ways in which families raise their children have significant implications for schools. Factors such as who takes care of children, how much supervision they receive, how much freedom they have, who speaks to them and how often, and what they are expected to do affect students' behavior on entering schools. Many of the misunderstandings that occur between teachers and students arise because of different expectations about behavior, and these different expectations stem from early, ingrained child-rearing practices. Because the largest group of English learners in California is of Mexican ancestry, teachers who take the time to learn about child-rearing practices among Mexican immigrants can help students adjust to schooling practices in the United States. An excellent source for this cultural study is Crossing Cultural Borders (Delgado-Gaitan & Trueba, 1991). Food Preferences and Practices As the numbers of school-provided breakfasts and lunches increase, food preferences are an important consideration. Furthermore, teachers who are knowledgeable about students' dietary practices can incorporate their students' background knowledge into health and nutrition instruction. Besides customs of what and when to eat, eating habits vary widely across cultures, and "good" manners at the table in some cultures are inappropriate or rude in others. For example, the Indochinese consider burping, lip smacking, and soup slurping to be common behaviors during meals, even complimentary to hosts. Cultural relativity is not, however, an excuse for poor or unhygienic eating. Teachers who supervise lunchrooms may need to teach students the behaviors that are considered good food manners in the U.S. mainstream context. Best Practice Dealing with Food Preferences . In addition to knowing in general what foods are eaten at home, teachers will want to find out about students' favorite foods, taboo foods, and typical foods. . Eating lunch with students, even by invitation only, can provide the opportunity to learn about students' habits. If a student's eating habits alienate peers, the teacher may need to discuss appropriate behaviors. Valuing Humanities and the Arts In many cultures, crafts performed at home-such as food preparation, sewing and weaving, carpentry, home building and decoration, and religious and ritual artistry for holy days and holidays-are an important part of the culture that is transmitted within the home. Parents also provide an important means of access to the humanities and the visual and performing arts of their cultures. The classroom teacher can foster an appreciation of the works of art, architecture, music, and dance that have been achieved by students' native cultures by drawing on the resources of the community and then sharing these with all members of the classroom. Cooperation Versus Competition Many cultures emphasize cooperation over competition. Traditional U.S. classrooms mirror middle-class European American values of competition: Students are expected to do their own work; are rewarded publicly through star charts, posted grades, and academic honors; and are admonished to do their individual best. In the Cree Indian culture, however, children are raised in a cooperative atmosphere, with siblings, parents, and other kin sharing food as well as labor (Sindell, 1988). Suina observes the psychological shock that he faced as a Pueblo Indian fitting in to higher education the University of New Mexico in the 1970s: Psychologically, too, it wasn't very easy, because there are two different sets of values involved, and two different paces of life. One is very individualistic: the focus is on the individual, the person, what you do. It's for you, you know? It's me, myself, and I, whereas the other one is much more group-oriented. It's community-oriented, where the people are interdependent, and the focus is on the group as opposed to the individual. So that was a very difficult psychological kind of movement back and forth. And then of course, the pace of life was a little bit different as well. The demands to do this and that were always so much more pressing at the college, it wasn't just a matter of taking responsibility. I could do that; I could take responsibility for my own actions and my own life. But it was that you had to push yourself to the forefront. (Suina, 2011 n. p.) A classroom structured to maximize learning through cooperation can help students extend their cultural predilection for interdependence. However, this interdependence does not devalue the uniqueness of the individual. In the Mexican American culture, interdependence is strength; individuals have a commitment to others, and all decisions are made together. Those who are successful have a responsibility to others to help them succeed. The Mexican culture values individualismo, the affirmation of an individual's intrinsic worth and uniqueness aside from any successful actions or grand position in society (deUnamuno, 1925). A workable synthesis of individualism versus interdependence would come from classroom activities that are carried out as a group but that affirm the unique gifts of each individual student. Adapting to Students' Culturally Supported Facilitating or Limiting Attitudes and Abilities A skilled intercultural educator recognizes that each culture supports distinct attitudes, values, and abilities that may either facilitate or limit learning in U.S. public schoo . For example, the cultures of Japan, China, and Korea, which promote high academic ach ement, may foster facilitating behaviors such as the ability to listen and follow directions, attitudes favoring education and respect for teachers and authorities, ideas of discipline as guidance, and high-achievement motivation. However, other culturally supported traits may hinder adjustment to the U.S. school, such as lack of previous participation in discussions; little experience with independent thinking; strong preference for conformity, which inhibits divergent thinking; and distinct sex-role differentiation, with males more dominant. Mexican American cultural values encourage cooperation, affectionate and demonstrative parental relationships, children's assumption of mature social responsibilities such as child care and translating family matters from English to Spanish, and eagerness to try out new ideas. All of these values facilitate classroom success. On the other hand, such attitudes as depreciating education after high school, especially for women; explicit sex-role stereotyping favoring limited vocational roles for women; emphasis of family over the achievement and life goals of children; and dislike of competition may work against classroom practices and hinder school success (Clark, 1983). Accommodating school routines is a schoolwide responsibility that is furthered when the principal sets the tone of appreciation and support for cultural diversity. Much can also be done by individual teachers in the classroom to set high standards of achievement that students and family members can support. Educating Students about Diversity Both mainstream students and CLD students benefit from education about diversity, not only cultural diversity but also diversity in ability, gender preference, and human nature in general. This engenders pride in cultural identity, expands the students' perspectives, and adds cultural insight, information, and experiences to the curriculum. Cultural content is an important part of education; it is a means by which students come to understand their own culture(s) as well as the mainstream U.S. culture. As Curtain and Dahlberg (2010) commented, The interests and developmental levels of the students in the class must guide the choice of cultural information selected for instruction.... Children penetrate a new culture through meaningful experiences with cultural practices and cultural phenomena that are appropriate to their age level, their interests, and the classroom setting. (p. 259) Global and Multicultural Education ELD teachers, as well as mainstream teachers who teach English learners, can bring a global and multicultural perspective to their classes. Language teachers, like teachers in all other areas of the curriculum, have a responsibility to plan lessons with sensitivity to the racial and ethnic diversity present in their classrooms and in the world in which their students live.... [Students) can learn to value the points of view of many others whose life experiences are different from their own. (Curtain & Dahlberg, 2010, p. 276) Table 10.1 lists some cultural activities that Curtain and Dahlberg recommended for adding cultural content to the curriculum. Table 10.1 Sample Cultural Activities for Multicultural Education Source: Curtain & Dahlberg, 2010. Activity Suggested Implementation Visitors and guest speakers Guests can share their experiences on a variety of topics, using visuals, slides, and hands-on materials. Many cultures can be represented; cultural informants can help. Folk dances, singing games, and other kinds of games Field trips Students can visit neighborhoods, restaurants, museums, or stores that feature cultural materials. Show-and-tell Students can bring items from home to share with the class. Read fables, folktales, or legends Read in translation or have a visitor read in another language. Read books about other cultures Age-appropriate fiction or nonfiction books can be obtained with the help of the school or public librarian. Cross-cultural email contacts Students can exchange cultural information and get to know peers from other lands. Magazine subscriptions Authentic cultural materials-written for adults or young people-give insight about the lifestyles and interests of others. There is a clear distinction between multiculturalism and globalism, although both are important features of the school curriculum: "Globalism emphasizes the cultures and peoples of other lands, and multiculturalism deals with ethnic diversity within the United States" (Ukpokodu, 2002, pp. 7-8). Did You Know? Studying Cultures Here and There James Banks explained the difference between studying the cultures of other countries and studying the cultures within the United States. For example, according to Banks, many teachers implement a unit on the country of Japan but avoid teaching about Japanese internment in the United States during World War II. Source: Brandt, 1994 The Multicultural Curriculum: From Additive to Transformative The goal of multicultural education is to help students to develop cross-cultural competence within a national culture, understanding and valuing their own subculture while being exposed to diverse other cultures. Banks introduced a model of multicultural education that has proved to be a useful way of assessing the approach taken in pedagogy and curricula. The model has four levels, represented in Table 10.2 with a critique of strengths and shortcomings taken from Jenks, Lee, and Kanpol (2002). Table 10.2 Banks's Levels of Multicultural Education with Critique Source: Model based on Banks, 1994; strengths and shortcomings based on Jenks, Lee, & Kanpol, 2002 Level Description Strengths Shortcomings Contributions Emphasizes what minority groups have contributed to society (examples: International Food Day, bulletin board display for Black History Month). Attempts to sensitize the majority White culture to some understanding of minority groups' history. May amount to "cosmetic" multiculturalism in which no discussion takes place about issues of power and disenfranchisement. Additive Adding material to the curriculum to address what has been omitted (reading The Color Purple in English class). Adds to a fuller coverage of the American experience, when sufficient curricular time is allotted. May be an insincere effort if dealt with superficially. Transformative Students learn to be reflective and develop a critical perspective. Incorporates the fallacy that discussion alone changes society. An expanded perspective is taken that deals with issues of historic, ethnic, cultural, and linguistic injustice and equality as a part of the American experience. Social Action Extension of the transformative approach to add students' research/action projects to initiate change in society. Students learn to question the status quo and the commitment of the dominant culture to equality and social justice. Middle-class communities may not accept the teacher's role, considering it as provoking students to "radical" positions. Similar to Banks's superficial-to-transformative continuum is that of Morey and Kilano (1997). Their three-level framework for incorporating diversity identifies as "exclusive" the stereotypical focus on external aspects of diversity (what they called the four f's: food, folklore, fun, and fashion); as inclusive the addition of diversity into a curriculum that, although enriched, fundamentally has the same structure; and as "transformed" the curriculum that is built on diverse perspectives, equity in participation, and critical problem solving. Thus, it is clear that pouring new wine (multicultural awareness) into old bottles (teacher-centered, one-size-fits- all instruction) is not transformative. Classroom Glimpse Transformative Multicultural Education Christensen (2000) described how her students were moved to action: One year our students responded to a negative newspaper article, about how parents feared to send their children to our school, by organizing a march and rally to *tell the truth about Jefferson to the press." During the Columbus quincentenary, my students organized a teach-in about Columbus for classes at Jefferson. Of course, these "spontaneous uprisings only work if teachers are willing to give over class time for the students to organize, and if they've highlighted times when people in history resisted injustice, making it clear that solidarity and courage are values to be prized in daily life, not just praised in the abstract and put on the shelf. (pp. 8-9) Validating Students' Cultural Identity "An affirming attitude toward students from culturally diverse backgrounds significantly impacts their learning, belief in self, and overall academic performance" (Villegas & Lucas, 2002, p. 23). Cultural identity-that is, having a positive self-concept or evaluation of oneself and one's culture-promotes self-esteem. Students who feel proud of their successes and abilities, self-knowledge, and self-expression, and who have enhanced images of self, family, and culture, are better learners. Of course, the most powerful sense of self-esteem is the result not solely of one's beliefs about oneself but also of successful learning experiences. Practices of schooling that damage self-esteem, such as tracking and competitive grading, undermine authentic cooperation and a sense of accomplishment on the part of English learners. Classroom Practices That Validate Identity Siccone (1995) described the activity Name Interviews in which students work in pairs using a teacher-provided questionnaire: "What do you like about your name? Who named you? Were you named for someone? Are there members of your family who have the same name?" This activity can be adapted for both elementary and secondary classrooms. Interested teachers might ask students to provide initial information about cultural customs in their homes, perhaps pertaining to birthdays or holidays. Through observations, shared conversations during lunchtime or before or after school, and group participation, teachers can gain understanding about various individuals and their cultures. Educators who form relationships with parents can talk about the students' perception of their own identity. Teachers can also ask students to interview their parents about common topics such as work, interests, and family history and then add a reflective element about their relationship and identification with these aspects of their parents' lives. Best Practice Cultural Content Promotes School Engagement In a study of 600 middle and high school teachers in Hawaii, Takayama and Ledward (2009) found that school engagement was higher on the part of students whose teachers drew upon the concepts of 'ohana (family), kaiaulu (community), and olelo (Hawaiian language) to create culturally relevant content, contexts, and assessments during classroom learning. School engagement includes "emotional engagement (students' feelings about teachers, other students, and school in general); behavioral engagement (inferred through positive conduct and adherence to rules); and cognitive engagement (willingness to exert effort in learning)." Source: Takayama & Ledward, 2009, p. 1 Instructional Materials That Validate Identity Classroom texts are available that offer literature and anecdotal readings aimed at the enhancement of identity and self-esteem. Identities: Readings from Contemporary Culture (Raimes, 1996) includes readings grouped into chapters titled "Name," "Appearance, Age, and Abilities," "Ethnic Affiliation Class," "Family Ties," and so forth. The readings contain authentic text and may be best used in middle or high school classes. Multicultural literature can enhance cultural and ethnic identity, but this is not always the case. The website Social JusticeBooks.org, a project of the nonprofit organization Teaching for Change (2017), hosts a link to the publication Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children's Books. This offers more than fifty lists of recommended books for children and young adults on multicultural topics, including stories of African Americans, Latinx, Arab Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, social justice, and multicultural children's literature. Another resource is Exploring Culturally Diverse Literature for Children and Adolescents (Henderson & May, 2005), with suggestions on how to help readers understand how stories are tied to specific cultural and sociopolitical histories. Promoting Mutual Respect among Students The ways in which we organize classroom life should make children feel significant and cared about-by the teacher and by one another. Unless students feel emotionally and physically safe, they will be reluctant to share real thoughts and feelings. Classroom life should, to the greatest extent possible, prefigure the kind of democratic and just society we envision and thus contribute to building that society. Together, students and teachers can create a "community of conscience," as educators Asa Hillard and George Pine call it (Christensen, 2000, p. 18). Mutual respect is promoted when teachers listen as much as they speak, when students can build on their personal and cultural strengths, when the curriculum includes multiple points of view, and when students are given the chance to genuinely talk to one another about topics that concern them. This can be accomplished using the Instructional Conversation discourse format (see Chapter 6 ). Learning about Students' Cultures Teachers can use printed, electronic, and video materials, books, and magazines to learn about other cultures. However, the richest source of information is local -the life of the community. Students, parents, and community members can provide insights about values, attitudes, and habits. One method of learning about students and their families, ethnographic study, has proved useful in illuminating the ways that students' experiences in the home and community compare with the culture of the schools. Ethnographic Techniques Ethnography is an inquiry process that seeks to provide cultural explanations for behavior and attitudes. Culture is described from the insider's point of view, as the classroom teacher becomes not only an observer of the students' cultures but also an active participant. Parents and community members, as well as students, become sources for the gradual growth of understanding on the part of the teacher. For the classroom teacher, ethnography involves gathering data to understand two distinct cultures: the culture of the students' communities and the culture of the classroom. To understand the home and community environment, teachers may observe and participate in community life, interview community members, and visit students' homes. To understand the school culture, teachers may observe in a variety of classrooms, have visitors observe in their own classroom, audio- and videotape classroom interaction, and interview other teachers and administrators. Observations Ideally, initial observations of other cultures must be carried out with the perspective that one is seeing the culture from the point of view of a complete outsider. Of course, when observing interactions and behaviors in another culture, one always uses the frame of reference supplied by one's own culture. This stance gradually changes as one adopts an ethnographic perspective. Observers need to be descriptive and objective and make explicit their own attitudes and values to overcome hidden sources of bias. This requires practice and, ideally, some training. However, the classroom teacher can begin to observe and participate in the students' culture, writing up field notes after participating and perhaps summing up the insights gained in an ongoing diary that can be shared with colleagues. Such observation can document children's use of language within the community; etiquettes of speaking, listening, writing, greeting, and getting or giving information; values and aspirations; and norms of communication. When analyzing the culture of the classroom, teachers might look at classroom management and routines; affective factors (students' attitudes toward activities, teachers' attitudes toward students); classroom talk in general; and nonverbal behaviors and communication. In addition to the raw data of behavior, the thoughts and intentions of the participants can also be documented. Interviews Two types of interviews can be used to gather information about students: structured and unstructured. Structured interviews use a set of predetermined questions to gain specific kinds of information. Unstructured interviews are more like conversations in that they can range over a wide variety of topics, many of which the interviewer would not necessarily have anticipated. As an outsider learning about a new culture, the classroom teacher would be better served initially by using an unstructured interview, beginning with general questions and being guided in follow-up questions by the interviewees' responses. The result of the initial interview may in turn provide a structure for learning more about the culture during a second interview or conversation. A very readable book about ethnography and interviewing is The Professional Stranger: An Informal Introduction to Ethnography (Agar, 1996), also provides an outline of various ethnographic techniques and guidelines. Home Visits The home visit is one of the best ways in which teachers can learn what is familiar and important to their students. The home visit can be a social call or a brief report on the student's progress that enhances rapport with students and parents. Scheduling an appointment ahead of time is a courtesy that some cultures may require and provides a means for the teacher to ascertain if home visits are welcome. The visit should be short (twenty to thirty minutes) and the conversation positive, especially about the student's schoolwork. Viewing the child in the context of the home provides a look at the parent-child interaction, the resources of the home, and the child's role in the family. Ernst-Slavit and Mason (n.d.) offer tips to teachers of English learners for pre-visit planning, what to do during the visit, and appropriate postvisit follow-ups. Classroom Glimpse Friday Night Dinners Emily Naisbit announces to her third-grade class each fall that she is available to visit students' homes for family dinners on Friday nights. One after another, students "book" her Fridays for their turn to host her. The families are delighted that she will visit and share their dinner meal. In this way, she gets to know each family in their home environment. Students as Sources of Information Students generally provide teachers with their initial contact with other cultures. Through observations, one-on-one interaction, and group participatory processes, teachers gain understanding about various individuals and their cultural repertoires. Teachers who are good listeners offer students time for shared conversations by lingering after school or opening the classroom during lunchtime. Questionnaires and interest surveys are also useful. Cary (2000) called this information about students their "outside story": "The outside story unfolds away from school and is built from a thousand and one experiences hooked to home and home country culture-family structure, language, communication patterns, social behavior, values, spirituality, and worldview" (p. 20). Best Practice A Teacher Explores the Hmong Culture Cary's Working with Second Language Learners: Answers to Teachers' Top Ten Questions (2000) details one teacher's exploration of the culture and homeland of a Hmong student, Ka Xiong. Lenny Rossovich, the teacher of the new fifth grader, used every resource from a school encyclopedia, websites (including the Hmong homepage), the local library, and one of Ka's uncles to learn more about the Hmong culture. Lenny even took a few Hmong language lessons on the Internet. Lenny's adventure toward understanding his student is an engrossing model. Families as Sources of Information Family members can be sources of information in much the same way as their children. Rather than scheduling one or two formal conferences, PTA open house events, and gala performances, the school might encourage family participation by opening the library once a week after school. This offers a predictable time during which family members and teachers can casually meet and chat. Families can also be the source for information that can form the basis for classroom writing. Using the language experience approach, teachers can ask students to interview their family members about common topics such as work, interests, and family history. In this way, students and family members together can supply knowledge about community life. Community Members as Sources of Information Community members are an equally rich source of cultural knowledge. Much can be learned about a community by walking or driving through it, or stopping to make a purchase in local stores and markets. Teachers may ask older students to act as tour guides. During these visits, the people of the neighborhood can be sources of knowledge about housing, spaces where children and teenagers play, places where adults gather, and sources of food, furniture, and services. Through community representatives, teachers can begin to know about important living patterns of a community. A respected elder can provide information about the family and which members constitute a family. A religious leader can explain the importance of religion in community life. Teachers can also attend local ceremonies and activities to learn more about community dynamics. The Internet as an Information Source about Cultures Websites proliferate that introduce the curious to other cultures. Webcrawler programs assist the user to explore cultural content using key word prompts. A search engine can locate websites with information about cultures commonly-or uncommonly-represented in U.S. schools. Culturally Inclusive Learning Environments Culturally responsive accommodations help teachers maintain culturally inclusive learning environments. But what characteristics of classroom and school environments facilitate culturally responsive accommodations to diverse communities? What Is a Culturally Supportive Classroom? A variety of factors contribute to classroom and school environments that support cultural diversity and student achievement. The most important feature of these classrooms is the expectation of high achievement from Engli