Question: Please read the questions Question: Please describe your thoughts concerning in this Chapter 5. Key Points 5 . In the United States the number of

Please read the questions

Question: Please describe your thoughts concerning in this Chapter 5.

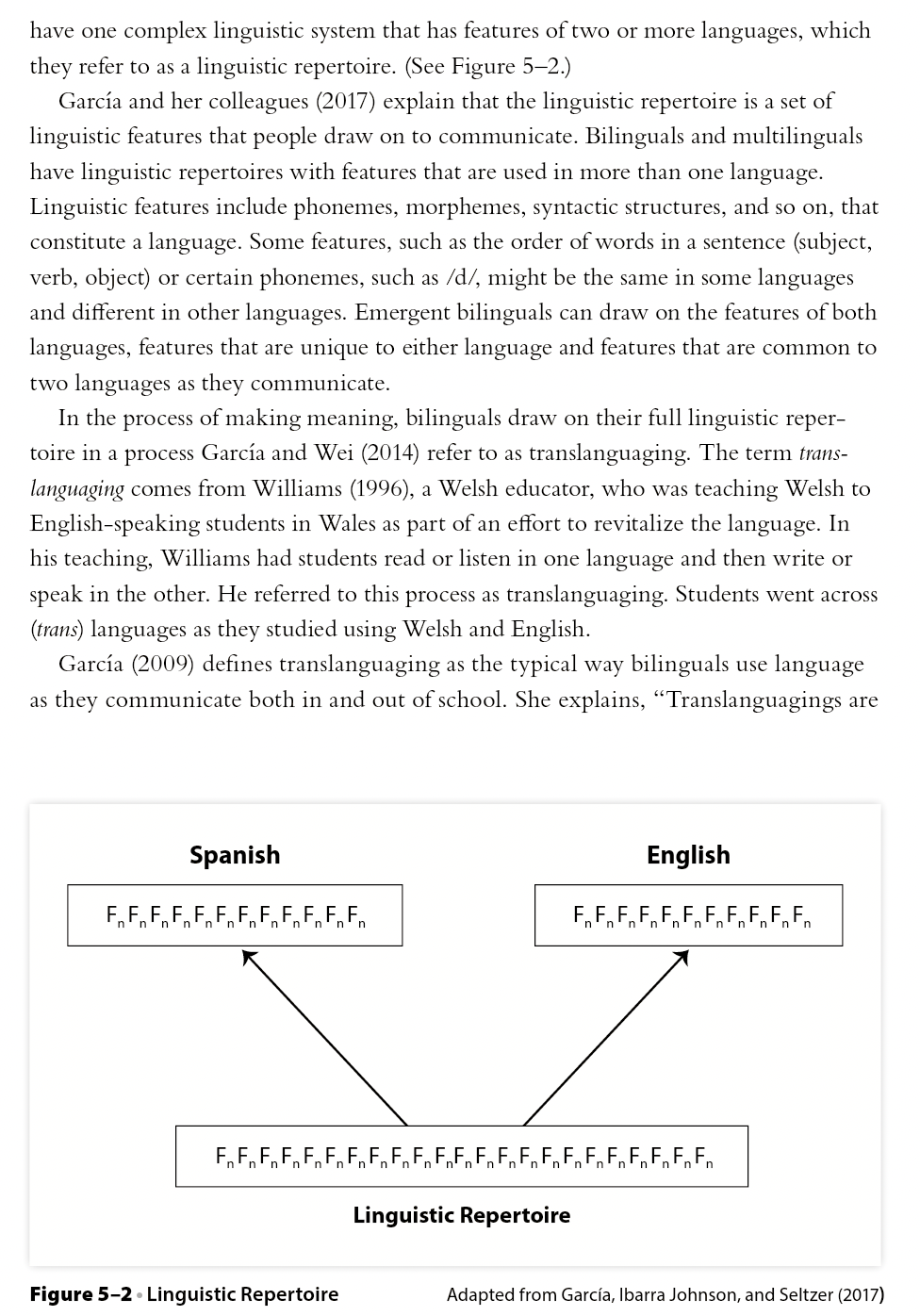

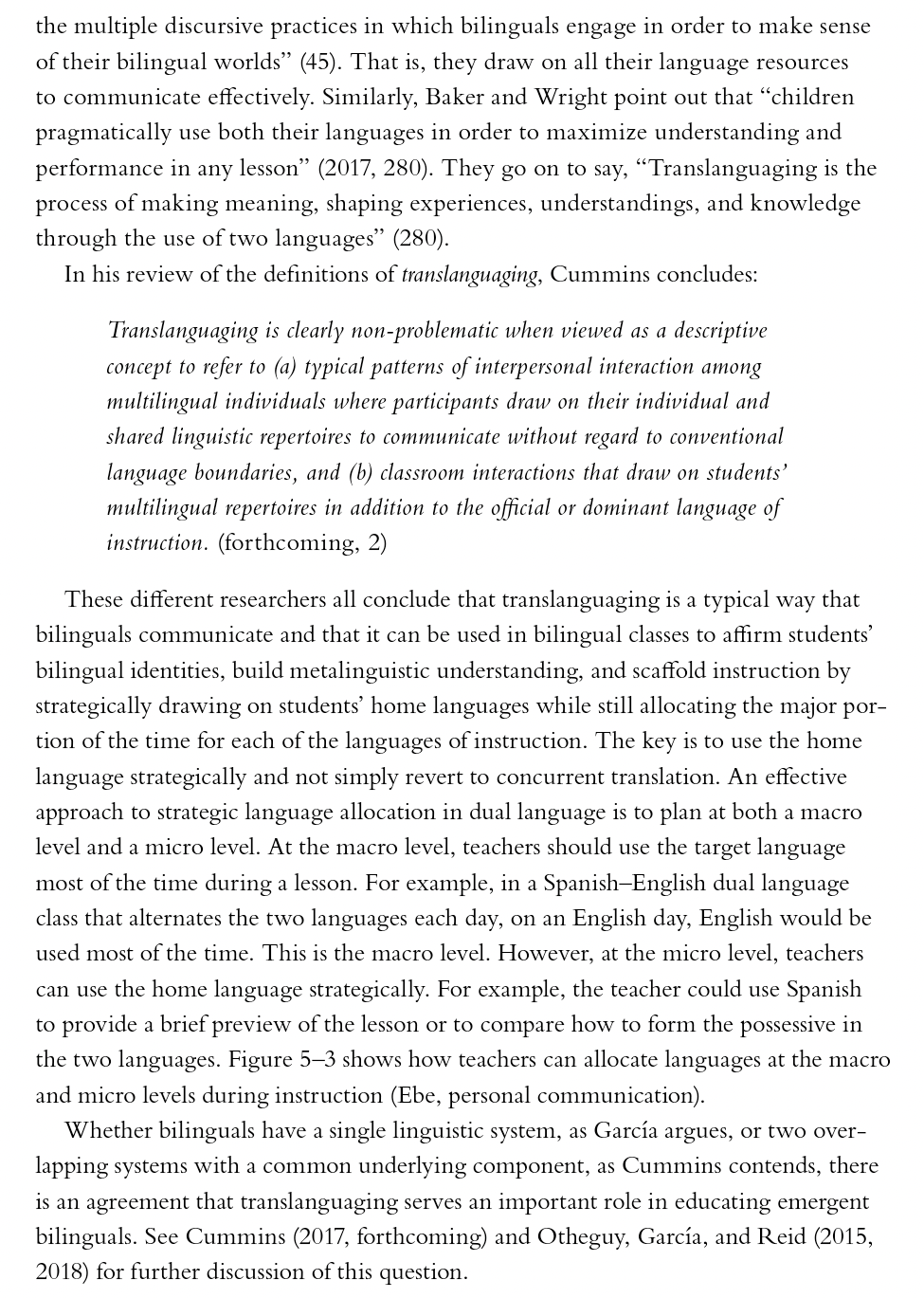

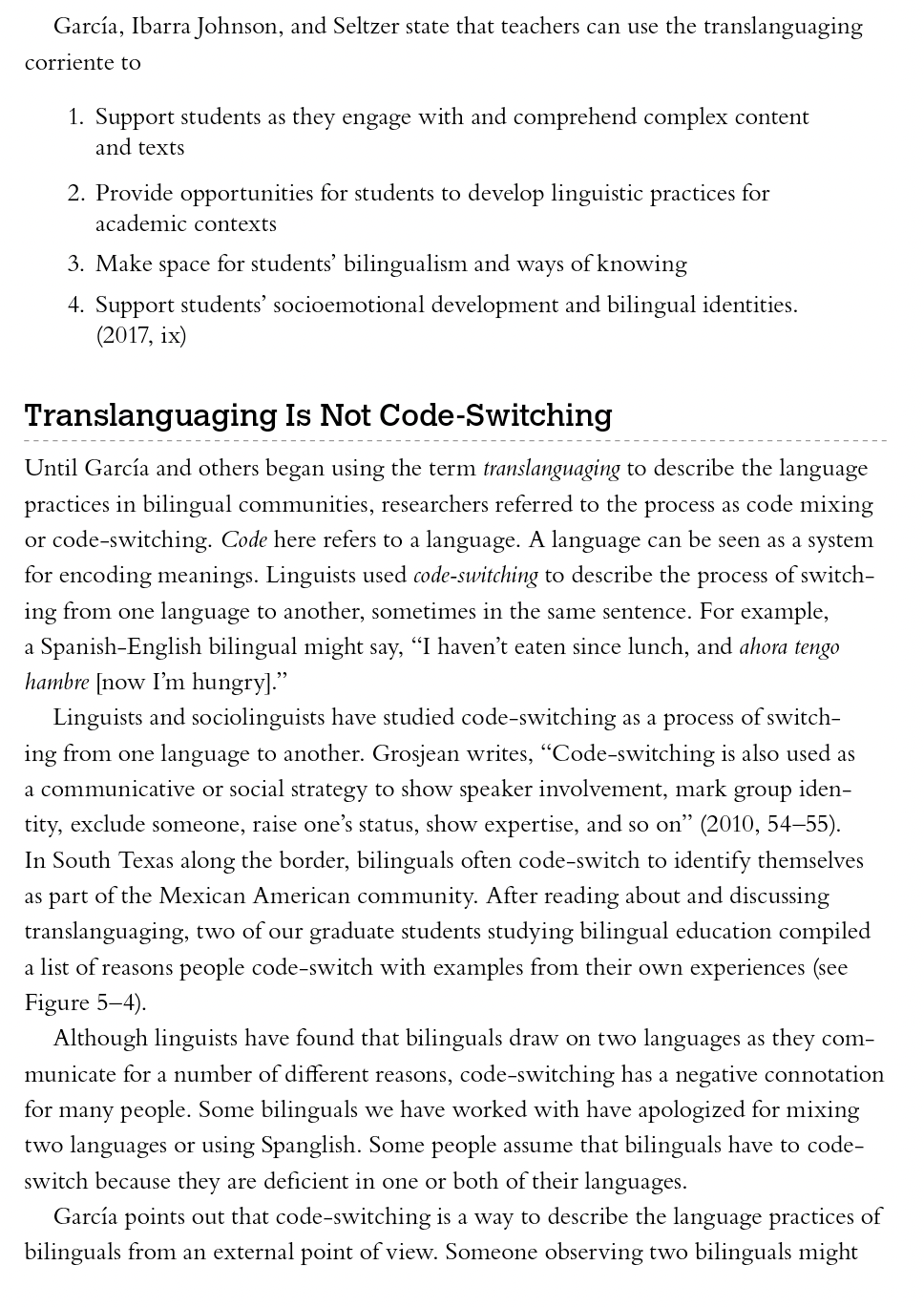

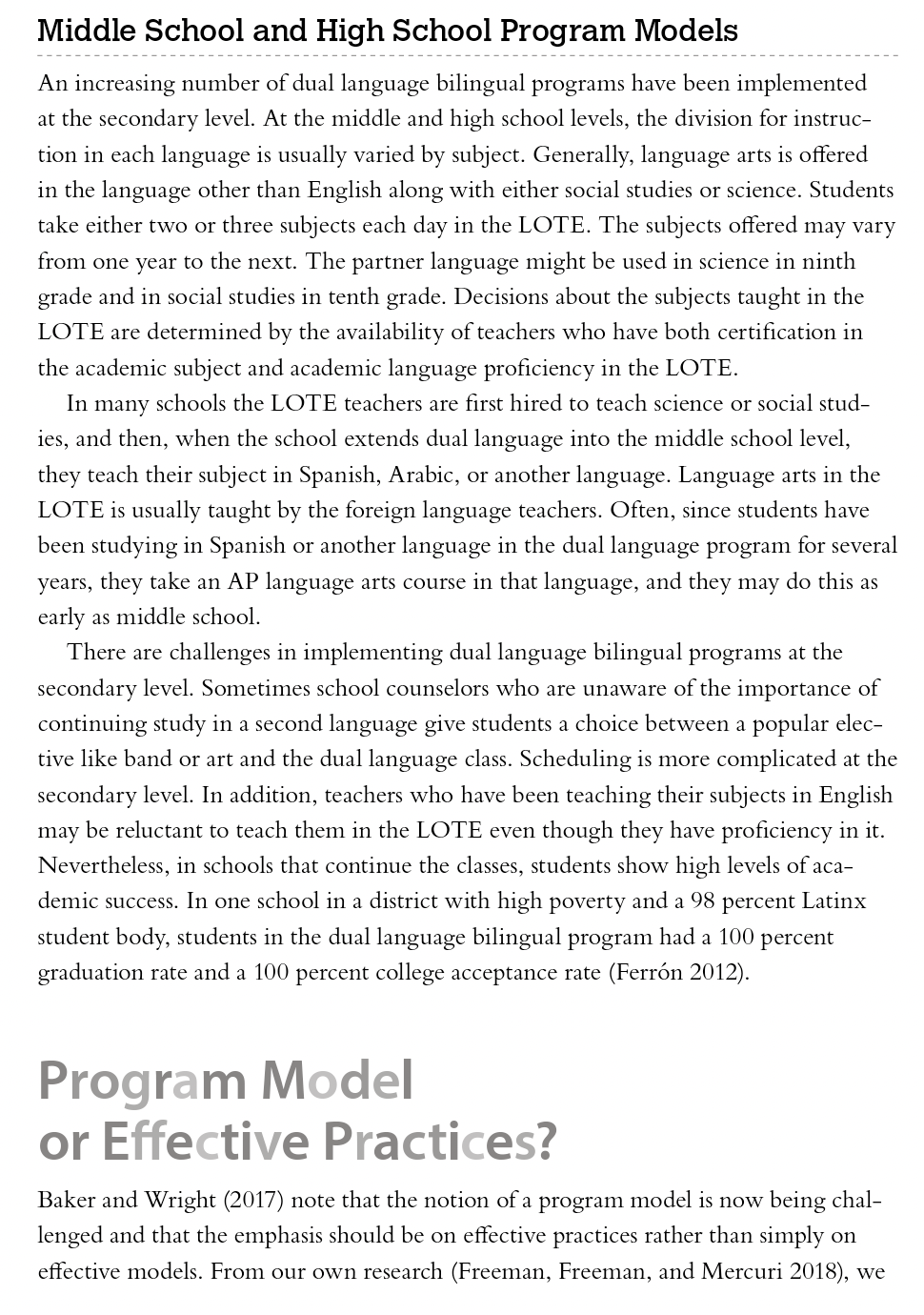

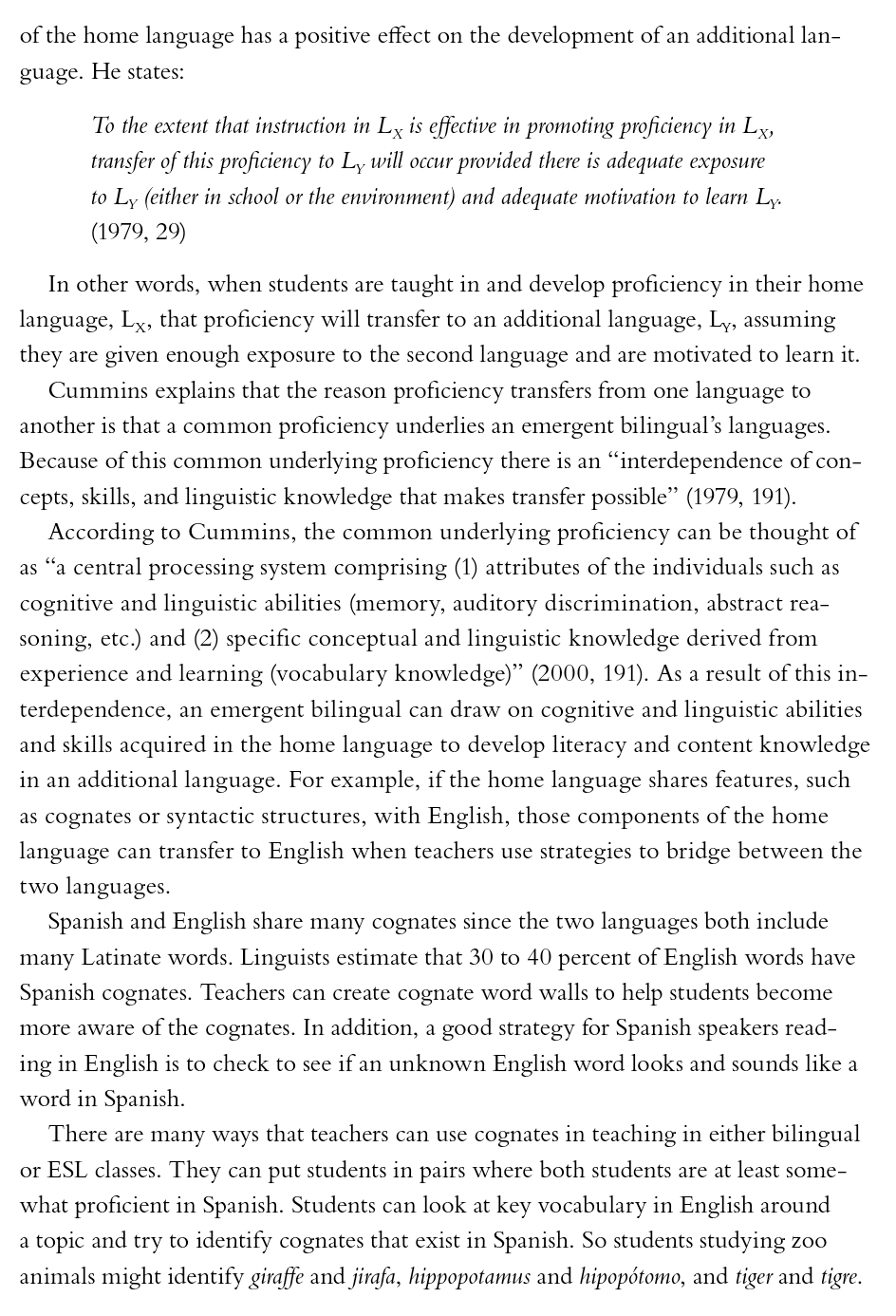

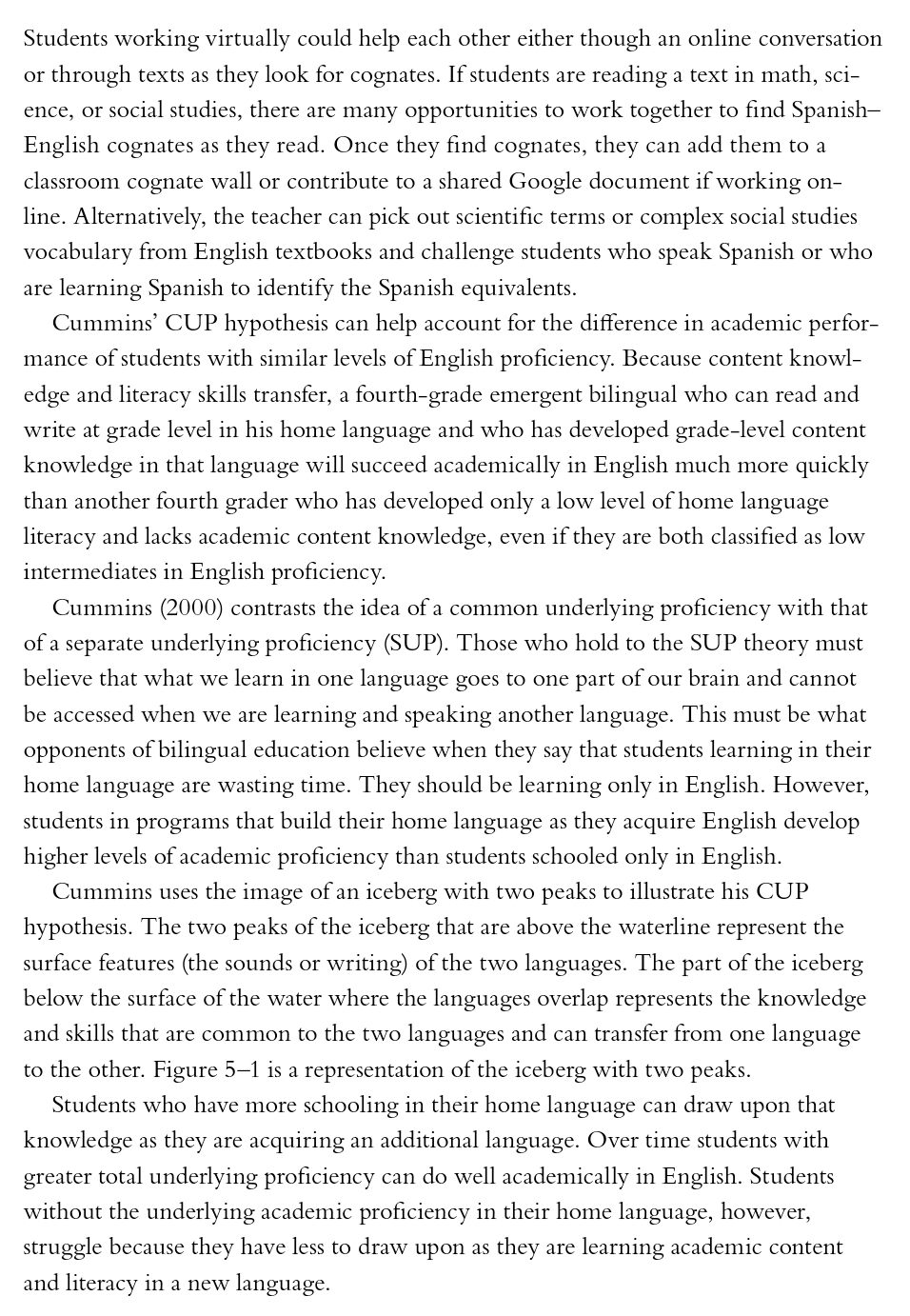

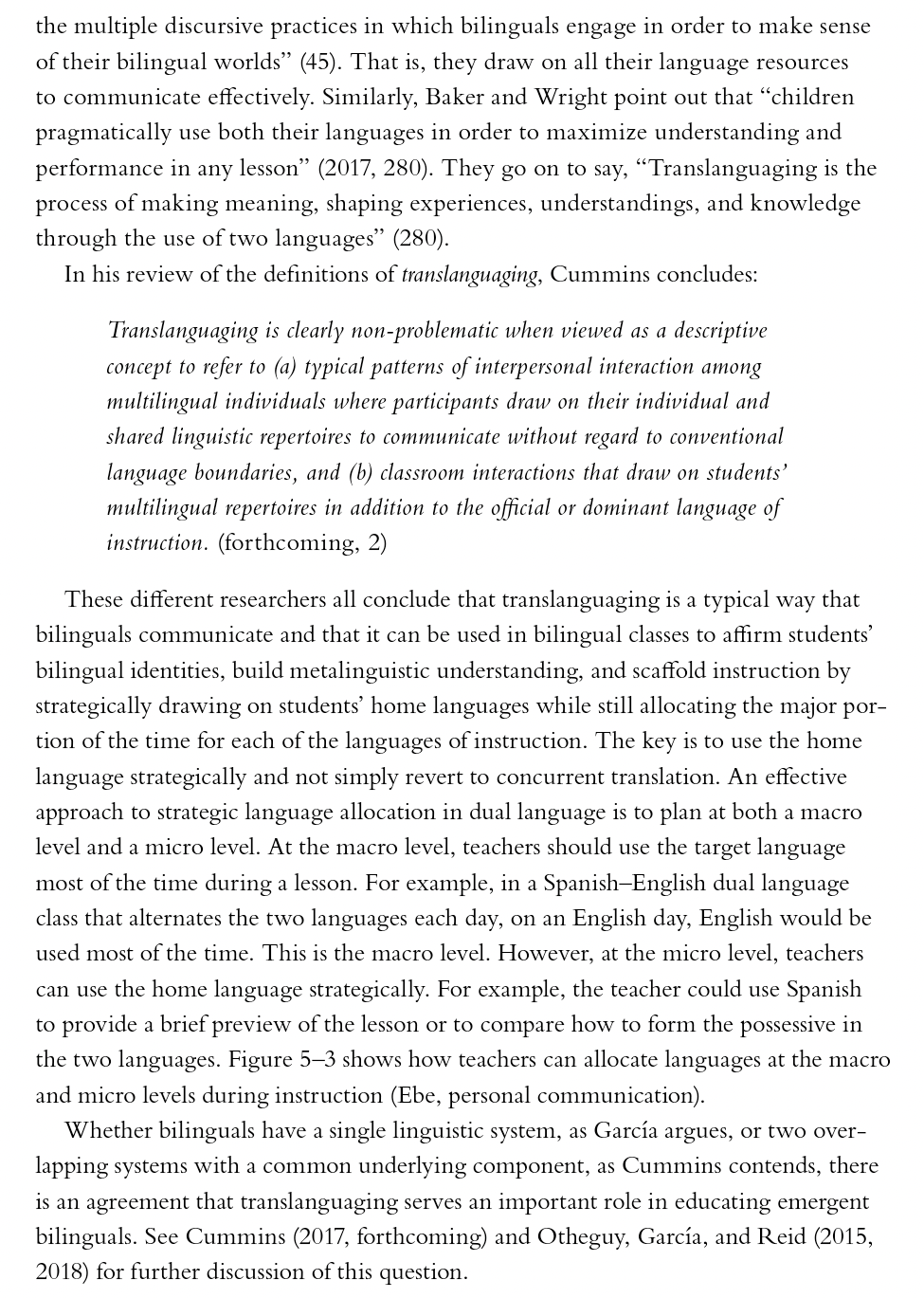

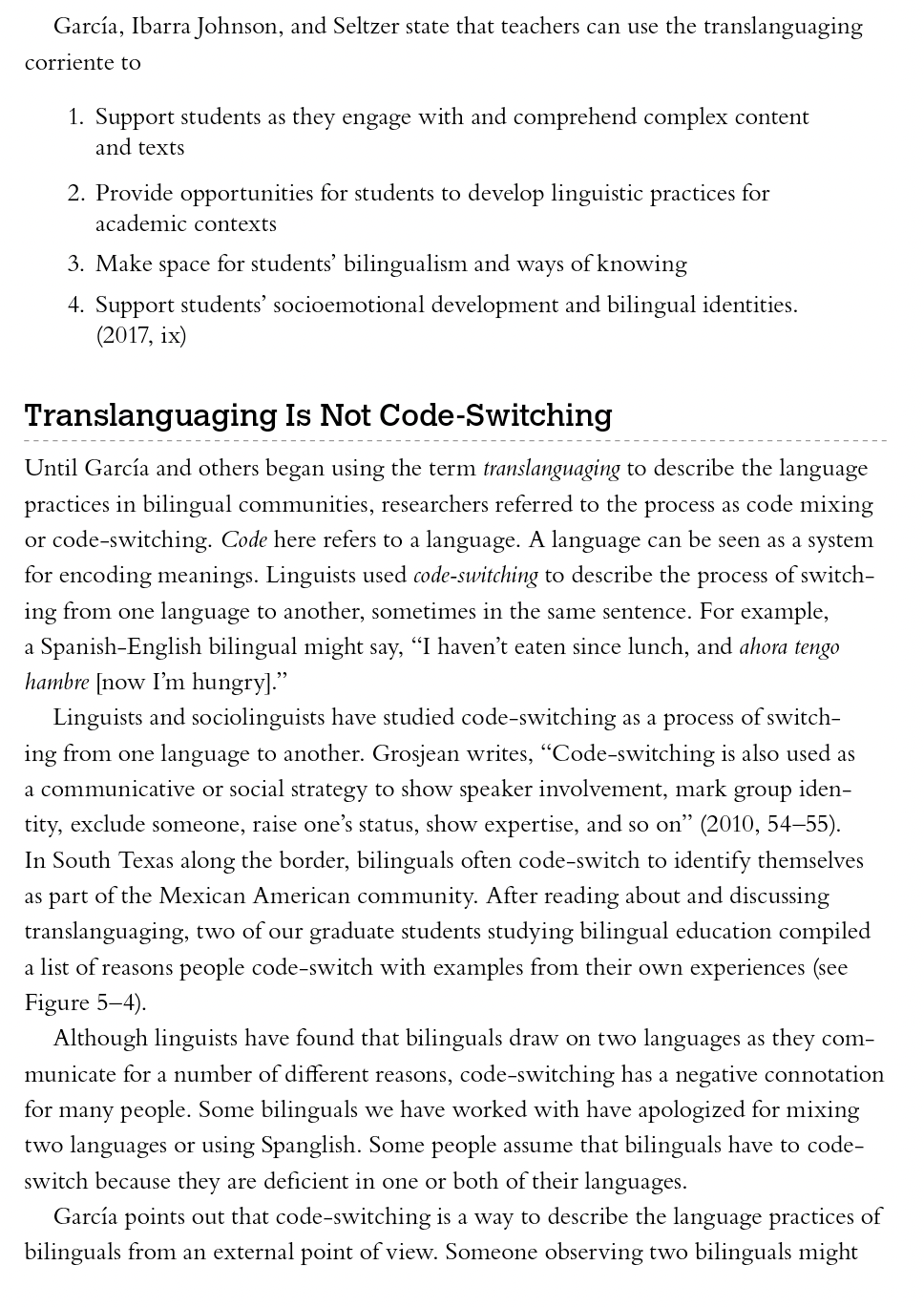

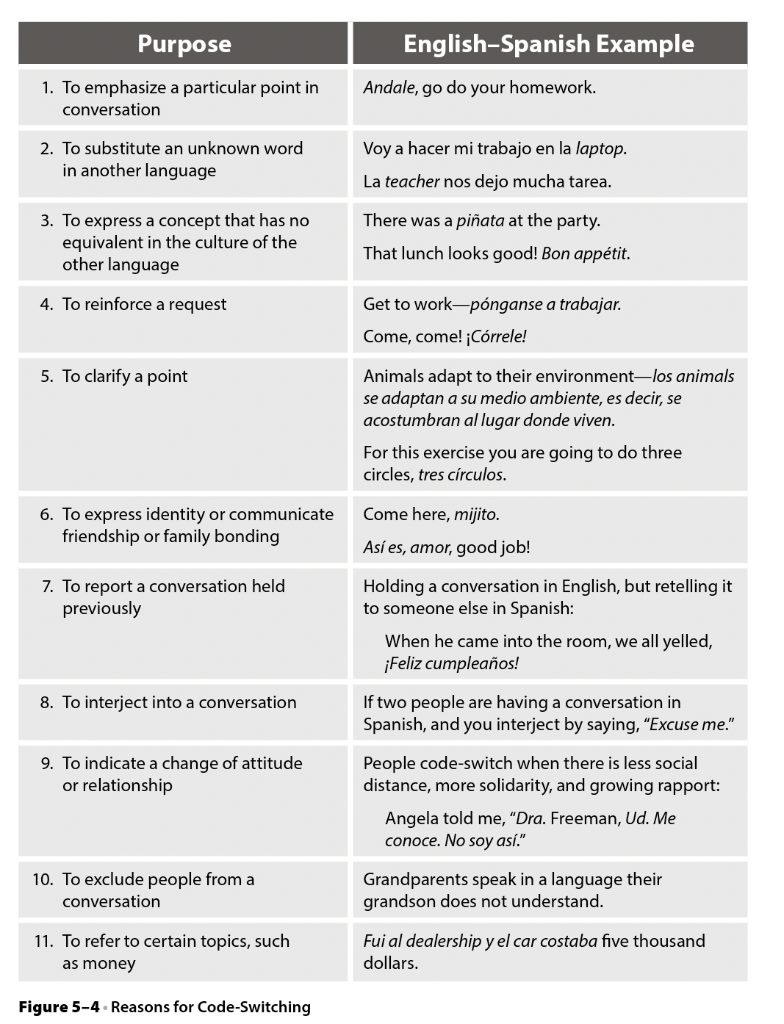

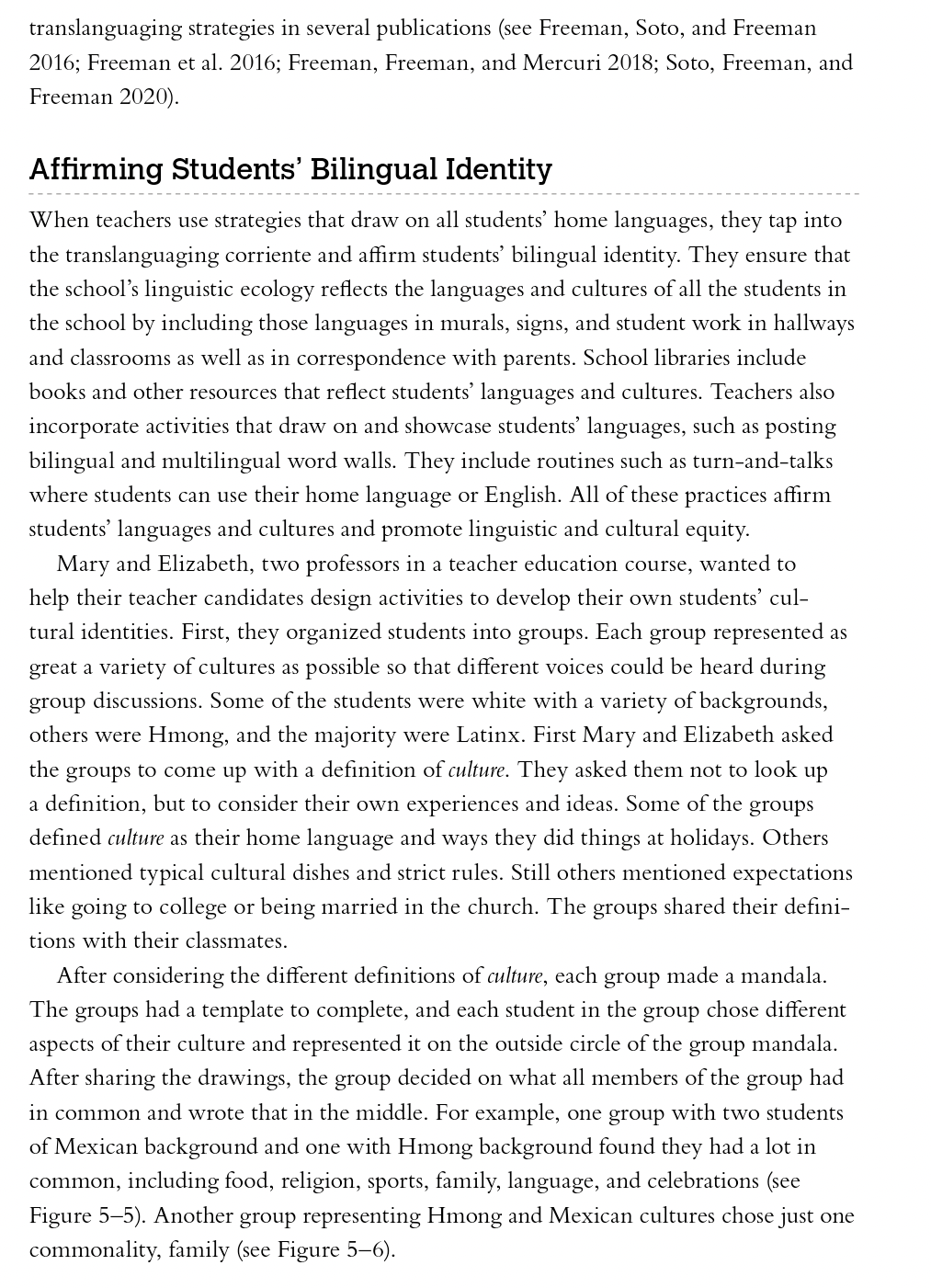

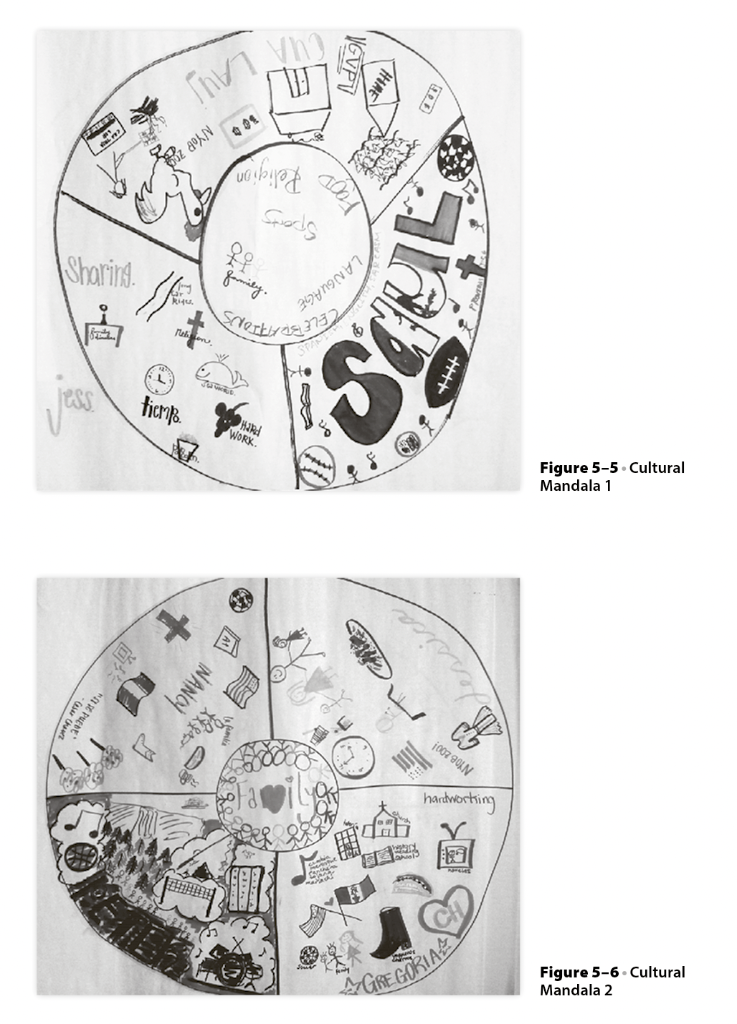

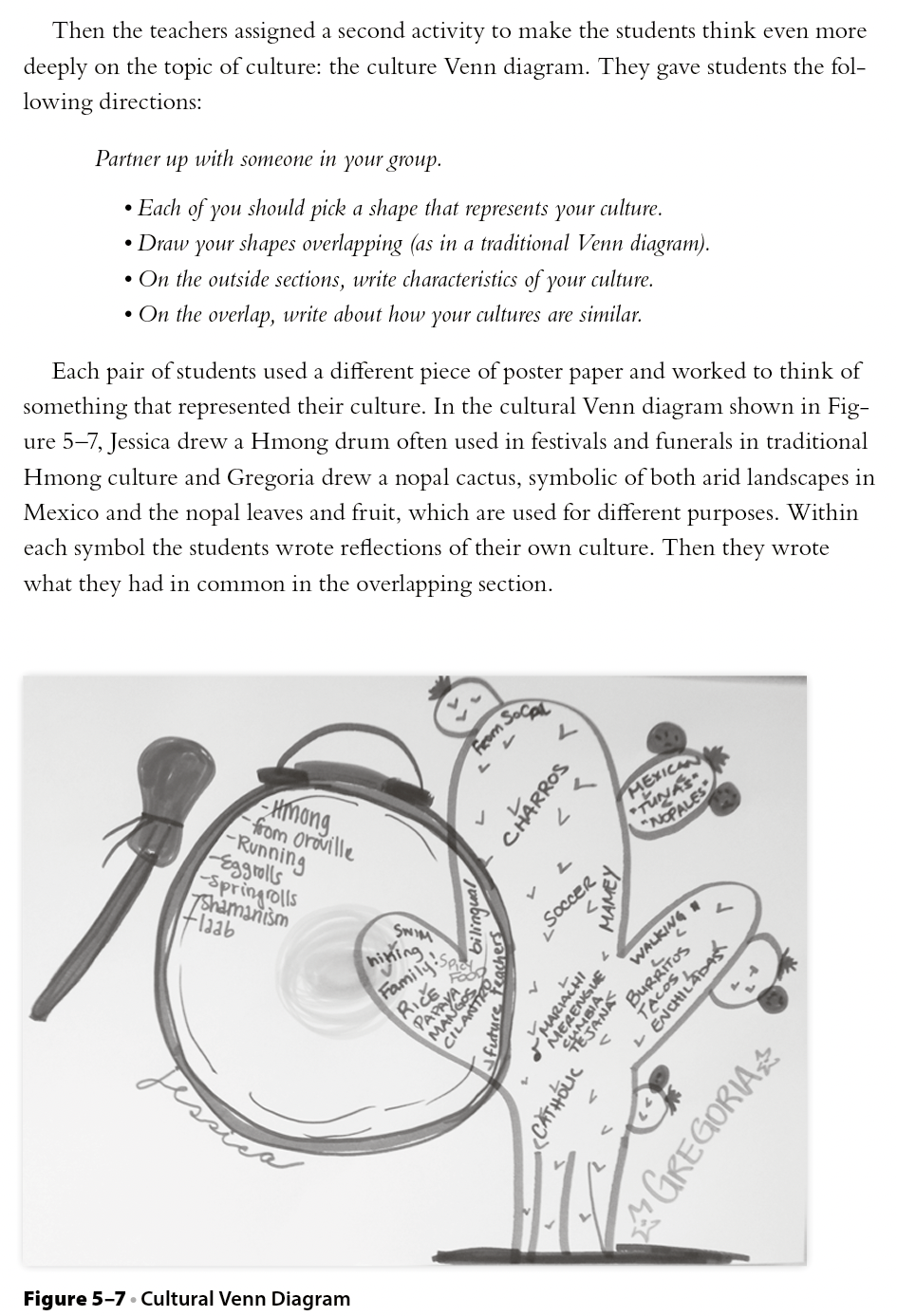

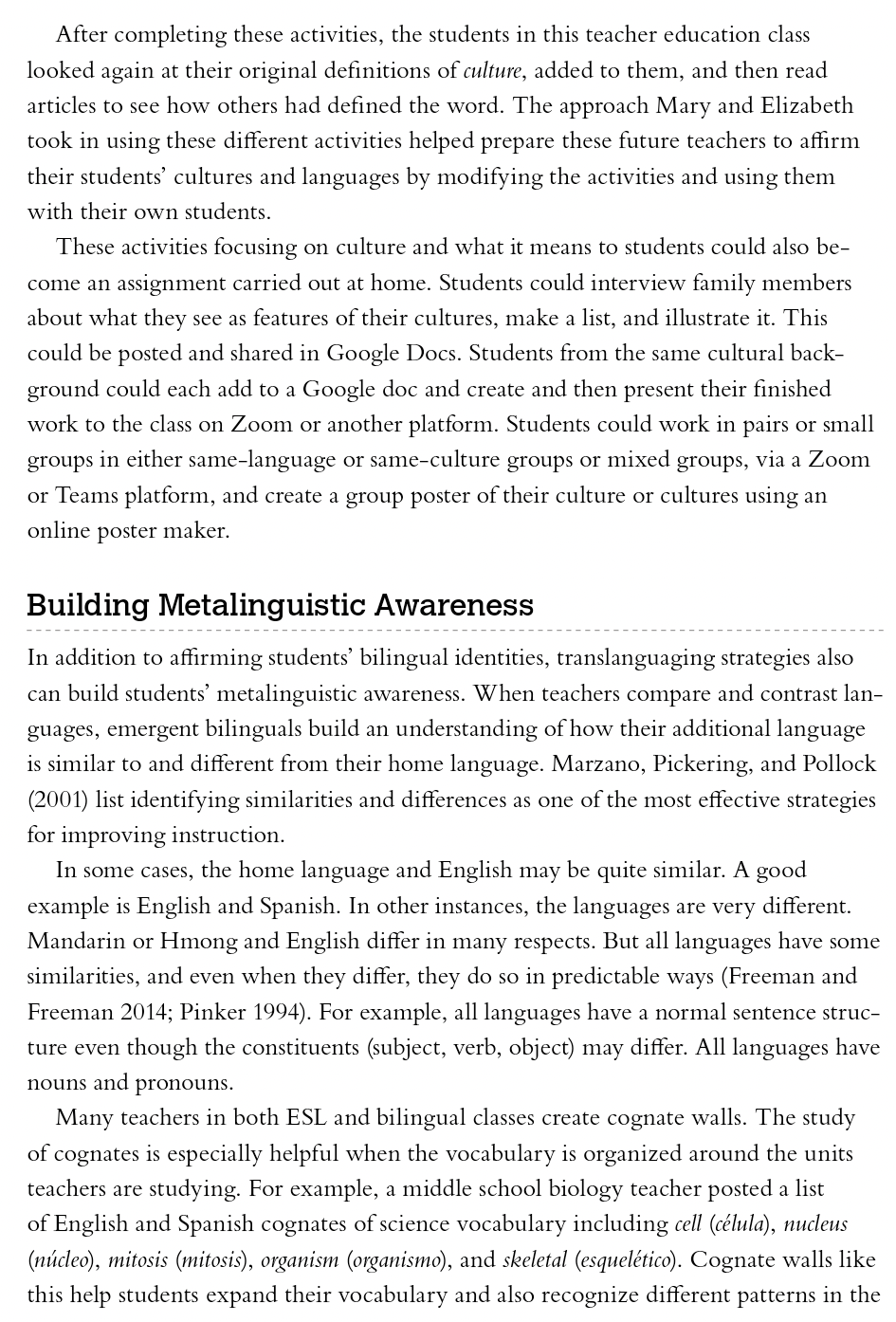

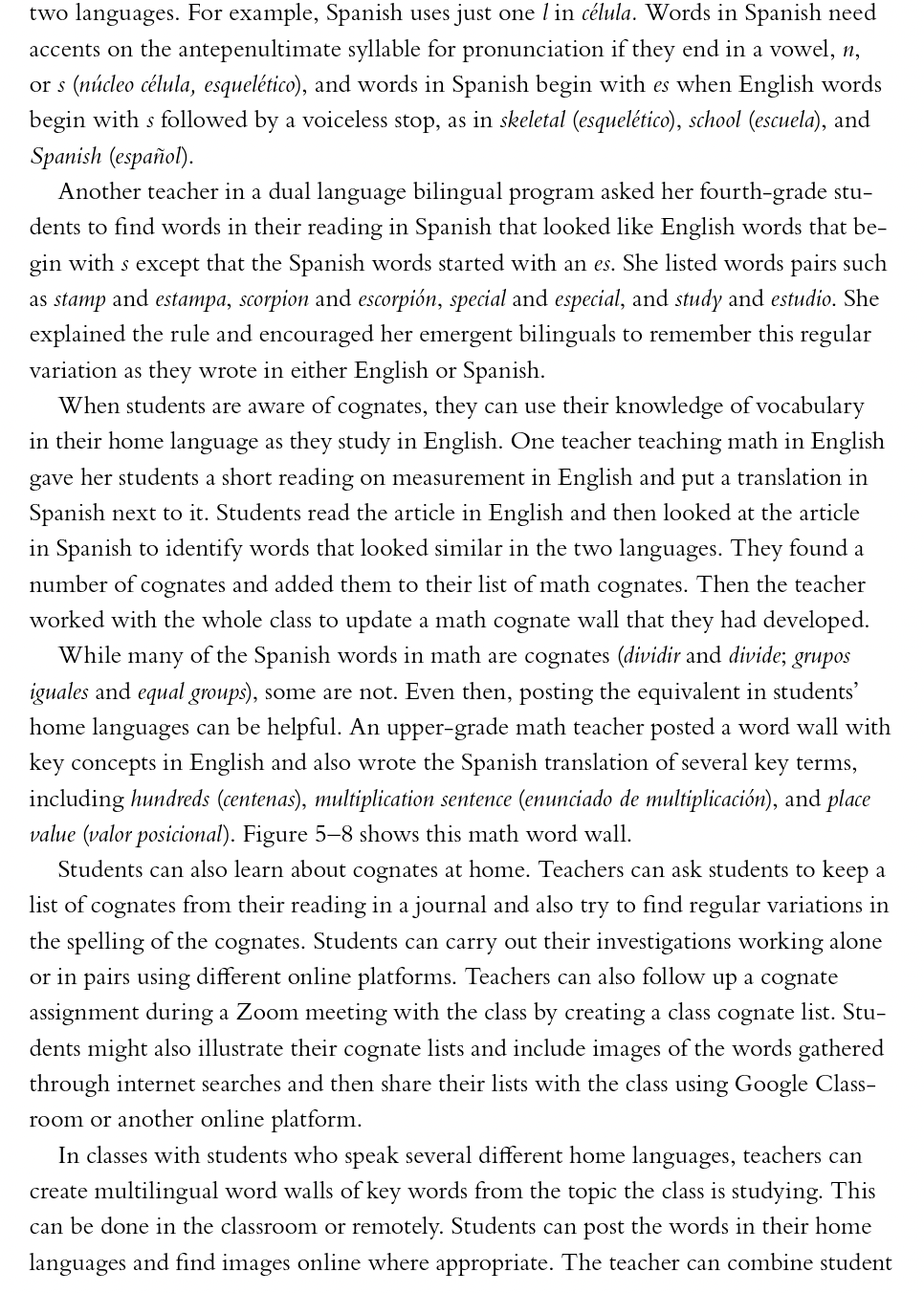

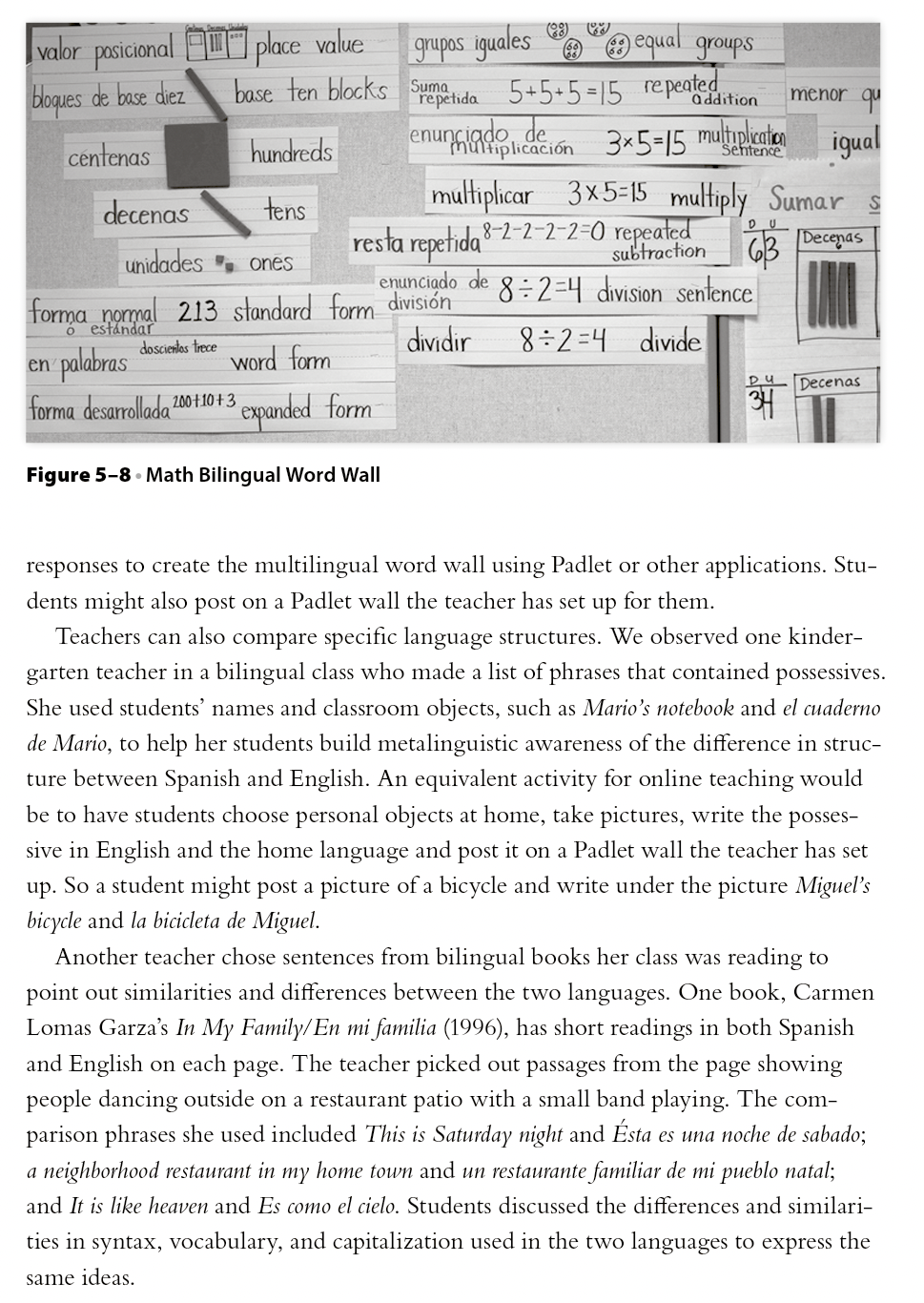

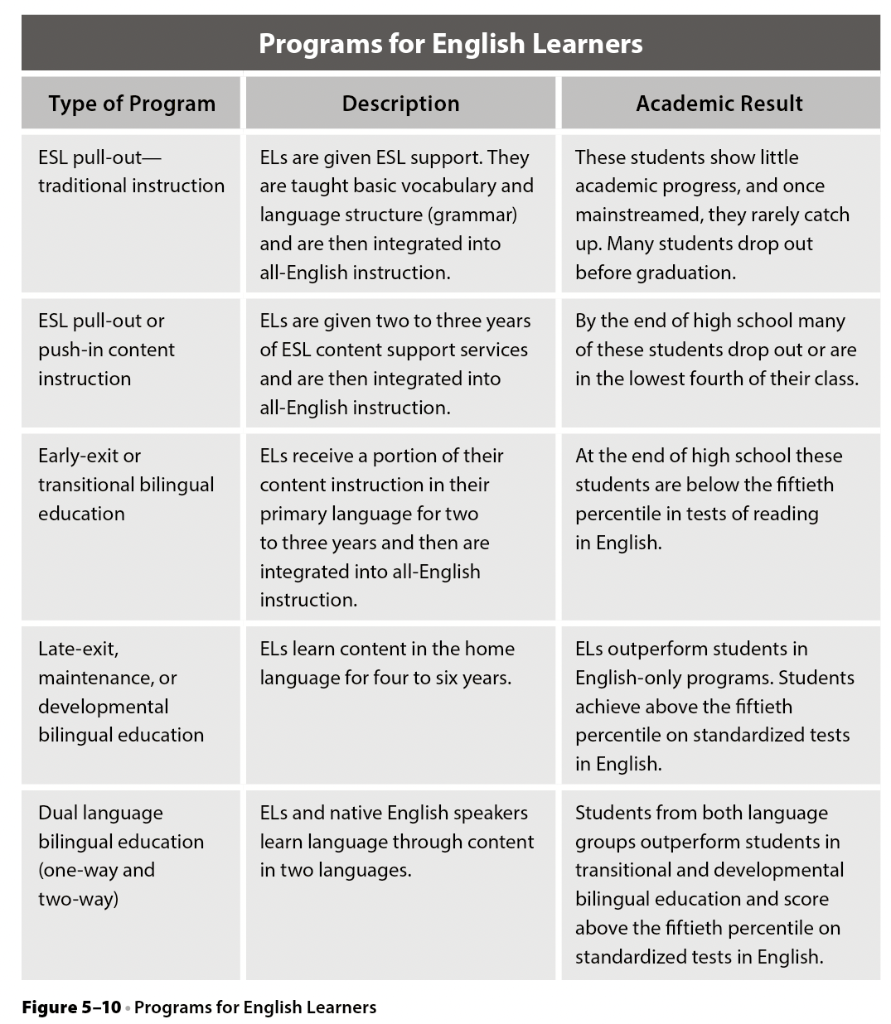

Key Points 5 . In the United States the number of bilinguals has steadily increased but monolingualism is still the norm. How Have Views of Bilinguals Changed and What Models Have Been Used to Teach Them? Bilinguals have greater cross-cultural competence than monolinguals. Bilingualism has linguistic, academic, economic, and cognitive benefits. Studies in neurolinguistics and sociolinguistics have led to changing views of bilinguals. Researchers have found that bilinguals are not balanced (equally competent in two languages). Two views of bilingualism are monoglossic and heteroglossic. A monoglossic view is that bilinguals are essentially two monolinguals in one person with two separate languages A heteroglossic view is that bilinguals have one complex linguistic repertoire that has features of two or more languages. It is a misconception that the two languages of a bilingual should be kept separate for instruction. Cummins conducted research showing that the languages of a bilingual have a common underlying proficiency and that the languages are interdependent Teachers can use translanguaging strategies to affirm students' bilingual identities, build metalinguistic awareness, and scaffold instruction Translanguaging is not code-switching. Schooling models for emergent bilinguals include ESL programs (pull-out, push-in, and stand-alone programs) and bilingual programs (early-exit, late-exit, and dual language programs). . Long-term dual language bilingual programs lead to more academic success for emergent bilinguals than other models. . The use of effective practices may be more important than the program model. Research in several fields, including neurolinguistics, sociolinguistics, and education, have contributed to a better understanding of emergent bilingual students. At the same time, the number of English learners in US schools has steadily increased, and the education of these students is no longer the sole responsibil- ity of an ESL teacher or a bilingual teacher. Rather, all teachers must be prepared to educate emergent bilinguals. Research on programs for English learn- ers has shown the effectiveness of well-implemented dual language bilingual models, and schools have responded to the changes in the school population by implementing more dual language bilingual programs designed to make all their students bilingual and biliterate. Bilingualism Around the World and in the United States Although estimates vary, there are around seven thousand languages found in the 192 countries in the world. Most of these countries are bilingual or multilingual. Grosjean (2010), looking at the numbers of countries and the numbers of languages in the world, estimates that at least half the world's population must be bilingual. In fact, with the exception of Iceland and possibly North Korea, the world's countries have almost always been inhabited by people who have spoken two or more languages (Grosjean 2010). Many of these bilinguals are really multilingual, especially if we accept Grosjean's definition of bilinguals as those who use two or more languages (or dialects) in their everyday lives (2010, 4). Baker and Wright have come to a similar conclusion: Bilinguals are present in every country in the world, in every social class, and in all I age groups. Numerically, bilinguals and multilinguals are in the majority in the world: it is estimated that they constitute between half and two thirds of the world's population. (2017, 60) " Although bilinguals are in the majority worldwide, for many people living in the United States, monolingualism is still considered the norm. While 56 percent of those polled in the European countries reported that they were fluent in at least one other language, Grosjean (2012) estimates that only around 20 percent of people living in the United States are bilingual and those include people who pair English with Native American languages, older colonial languages, recent immigrant languages, American Sign Language, and so on. Reports show that the number of bilingual and multilingual people in the United States has steadily increased. According to a Migration Policy Institute report on language diversity in the United States by Batalova and Zong (2016), 60 percent of those who do speak a language other than English at home reported that they are also fully English proficient; that is, they are bilingual. The number of immigrants and US natives speaking a language other than English at home represents one in five US residents. Grosjean (2020) in a recent blog and using a different database concluded that the number of bilinguals in the US is about 63 million people. As the US population becomes more diverse, schools reflect this increasing linguis- tic and ethnic diversity. The changes in school populations bring a challenge because many more students at all grade levels have limited English proficiency. For that rea- son, all teachers need to develop a better understanding of how best to educate classes that include many emergent bilinguals. a Linguistic and Cultural Capital Many different languages are spoken in the United States but until recently schools have privileged English and have not promoted the development of English learners' home languages. One reason for this is that in much of the world, English is associ- ated with prestige. Certainly, in the United States those who speak English well have linguistic capital (Bourdieu and Passeron 1977), a kind of power that those who do not speak the language well do not have. There are other kinds of capital. Students from the dominant culture who understand how things are done within a culture have cultural capital. Students coming to school with a home language other than English have neither linguistic nor cultural capital when they begin school. As they are learning English, they lack this power because they are not yet proficient in either the language or the cultural practices. Even people who speak two or three languages other than English daily may lack linguistic capital because the languages they are using are not valued, and their skills at using their home languages are not appreciated. English and other major languages are so predominant that speakers of other languages come to see the dominant languages as more important than their own. Many speakers shift from their native tongues to the power language, giving up not only their language but also their culture in the process. However, education in the twenty-first century is beginning to change to reflect the realities of our rapidly changing world. Not only are science, math, and technol- ogy important, but so is the ability to read, write, and speak two or more languages. Policy makers and educators have recognized the critical need for Americans to be- come multilingual in the growing global economy. When former Secretary of Educa- tion Riley highlighted the dual language approach as the most effective way to teach English and encourage biliteracy, he pointed out that language is at the core of the Latino experience in this country, and it must be at the center of future opportunities. It is high time we begin to treat language skills as the asset they are (Riley 2000). Benefits of Bilingualism When emergent bilinguals develop high levels of linguistic proficiency in English and in an additional language, their linguistic and cultural capital greatly increase. The linguistic advantages are obvious. Bilinguals can communicate in more con- texts with more people than monolinguals can. This proves beneficial when people travel to other countries as well as when they communicate with people living in the United States who do not speak English or do not speak it well. The linguistic benefits of bilingualism also result in academic, economic, and cognitive benefits. In addition, bilingual programs help all students develop cross-cultural competence and global awareness, one of the interdisciplinary themes listed in the Partnership for 21st Century Learning (2019) framework. The framework lists several skills as part of global awareness. They include . using twenty-first-century skills to understand and address global issues learning from and working collaboratively with individuals representing diverse cultures, religions, and lifestyles in a spirit of mutual respect and open dialogue in personal, work, and community contexts understanding other nations and cultures, including the use of non- English languages. (2) Copyright 2020, Battelle for Kids. All rights reserved. www.bfk.org. . Academic Benefits of Becoming Bilingual In a review of research on dual language, Lindholm-Leary (2020) found that emergent bilinguals achieve at or above grade-level norms in English reading and writing by grades 57" and native English speakers acquire the same or higher levels of English competence as their peers in mainstream programs (2). In a longitudinal study of a large district, Valentino and Reardon (2014) analyzed the standardized test scores of 13,750 bilinguals in English language arts each year from second through eighth grade and in math from second to sixth grade. They compared results for students in the different programs that the district offered: En- glish immersion, transitional bilingual, developmental bilingual, and dual language bilingual programs. The longitudinal data for tests of English language arts showed that while the scores of learners in English immersion, transitional bilingual, and developmental bilingual programs all increase at about the same rate as the state average for all students, scores for students in dual language bilingual classes increase more rapidly than the state average. Valentino and Reardon comment, This rate is so fast, that by fifth grade their test scores in ELA catch up to the state average, and on average by seventh grade Els in DI are scoring above their EL counterparts in all of the other programs (21). Collier and Thomas (2009) conducted a series of large-scale long-term studies on dual language programs in different parts of the United States. They consistently found that by sixth grade students in dual language bilingual programs score higher than native English speakers in national norms on standardized tests of reading and math in English. In addition, several meta-analyses have shown that bilinguals in well-implemented, long-term bilingual education programs succeed academically at higher rates than students in transitional bilingual programs or ESL programs (Greene 1998; Rolstad, Mahoney, and Glass 2005; Slavin and Cheung 2003). As these studies all show, emer- gent bilinguals in programs that develop high levels of proficiency in both their home language and English succeed academically at higher levels than other English learners and, when the programs are long-term, they also succeed academically at higher levels than monolingual English speakers. Economic and Cognitive Benefits of Becoming Bilingual In addition to the linguistic and academic advantage, programs that develop students' bilingualism provide economic and cognitive advantages for all students. Callahan and Gndara, in The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy, and the US Labor Market (2014), provide evidence of the economic benefits of bilingualism. The chapters present empirical studies from researchers in education, economics, sociology, anthropology, and linguistics showing the economic and employment benefits of bilingualism in the US labor market. Unlike previous studies, this book focuses on individuals who have developed high levels of bilingualism and biliteracy. Such people have greater employ- ment potential than monolinguals. Our own daughters, Ann and Mary, have both benefited from developing high levels of bilingualism and biliteracy. They started their education in a bilingual school in Mexico City and returned after two years to the United States, where they con- tinued to develop their bilingualism in a dual language school in Tucson, Arizona. In Tucson they became friends with three teens from El Salvador who had been given asylum in the United States and spoke Spanish with them. Later, Ann attended a semester of high school in Mexico City, and Mary married a man from El Salvador. More recently, Ann's husband was assigned to work for his company in Mexico City, and the family lived there for four years. Their bilingualism has helped them in their teaching. Ann taught in Spanish and English in an elementary school, and Mary taught drama in Spanish at a high school and later taught classes for secondary English learners. Both completed their doctorates and have taught in bilingual programs at the university level. Their bilingualism and biliteracy enabled them to find employment at both the K-12 and university levels. Being bilingual has cognitive advantages as well. Bialystok (2007, 2011) has con- ducted a series of studies showing that bilinguals have better problem-solving ability than monolinguals. In addition, her studies have shown that bilinguals have lower rates of dementia and Alzheimer's disease than monolinguals. She reports, The main empirical finding for the effect of bilingualism on cognition is in the evidence for enhanced executive control in bilingual speakers (2011, 1). Hamayan, Genesee, and Cloud explain the concept of executive control functions: a The advantages of bilingualism have been demonstrated in cognitive domains related to attention, inhibition, monitoring, and switching focus of attention. These processes are required during problem solving, for example, when students must focus their attention if potentially conflicting information needs to be considered; in order to select relevant information and inhibit processing of irrelevant information; and when they must switch attention to consider alternative information when a solution is not forthcoming. Collectively, these cognitive skills comprise what are referred to as executive control functions. (2013, 8) As Bialystok points out, considerable research has shown that both languages of a bi- lingual speaker are constantly active, even in contexts where only one language is being used. As a result, bilinguals must use the executive control functions during linguistic processing. She comments, A likely explanation for how this difficult selection is made in constant online linguistic processing by bilinguals is that the general-purpose execu- tive control system is recruited into linguistic processing, a configuration not found in monolinguals (2011, 2). She argues that the result of constantly using the executive control system in linguistic processing changes bilinguals' brains in ways that improve the ability to solve problems and resist diseases like dementia and Alzheimer's. Hamayan, Genesee, and Cloud point out that the bilingual advantage found by Bialystok is most evident in bilingual people who acquire relatively advanced levels of proficiency in two languages and use their two languages actively on a regular basis (2013, 7). Well-implemented dual language bilingual programs are long-term and help students develop the high levels of bilingualism and biliteracy needed for the cognitive benefits of bilingualism. As these studies show, when students develop high levels of bilingualism and biliteracy, they derive a number of benefits. While English learners in ESL programs and in short-term bilingual programs generally score below native English speakers in standardized tests of reading and math in English, emergent bilinguals in long-term bilingual programs where they become bilingual and biliterate succeed academically at higher levels than monolingual students and also gain linguistic, economic, and cogni- tive benefits. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Can you think of specific examples of the benefits of bilingualism that you have, your students have, or bilinguals you know have? Share with a partner or small group. Changing Views of Bilinguals and Bilingualism Changes in our understanding of bilingualism can help educators develop effective programs for teaching emergent bilinguals. In addition to research in cognitive science (Bialystok 2011), studies in sociolinguistics and education have provided a better understanding of bilingualism (Cummins 1979, 2000; Garca and Wei 2014; Grosjean 2010). This research has implications for language use in programs for emergent bilin- guals. However, a misconception about bilingualism has led to pedagogical practices that make learning more difficult for bilinguals. Misconception of Balanced Bilinguals One commonly held misconception has been that the goal of bilingual education should be to produce balanced bilinguals. A balanced bilingual is someone who is equally competent in two languages. This would mean that students in a bilingual Mandarin-English program should develop the ability to understand, speak, read, and write both English and Mandarin equally well in all settings. An image used to represent the two languages of a balanced bilingual is a bicycle with two wheels that are the same size and do the same work. In contrast, a monolin- gual is represented by a unicycle (Cummins 2001). The concept of a balanced bilin- gual comes from the perspective of a monolingual person. From this view, a student in a dual language program would start as a monolingual in one language and then add a second language to become two monolinguals in one person. However, studies in cognition have found that bilinguals are not simply two mono- linguals. Over time, the neural structures in the brain of a bilingual change as the result of using two languages. Bialystok observed that the lives of bilinguals included two languages, and their cognitive systems therefore evolved differently than did those of monolingual counterparts (2011, 8). As Bialystoks studies in neurolinguistics have shown, the neural networks of bilinguals are modified to accommodate their devel- opment and use of two languages. In very fundamental ways, bilinguals are different from monolinguals because of their experience of living with two languages. Studies in sociolinguistics give further evidence that bilinguals should not be viewed as two monolinguals in one person. Rather than picturing a bilingual as two monolinguals, Grosjean (2010), a sociolinguist, takes a holistic view. He argues that the bilingual is an integrated whole who cannot easily be decomposed into two sepa- rate parts he has a unique and specific linguistic configuration" (75). Grosjean compares a bilingual to a high hurdler in track and field. The hurdler has to have the skills of a high jumper and the skills of a sprinter and combines both jumping high and running fast into a new and different skill. High hurdlers don't have to jump as high as high jumpers or run as fast as sprinters. High hurdlers have unique skills combining the two. Bilinguals seldom speak both languages perfectly in all set- tings, but they should be valued for the skills they have as bilinguals. The Complementarity Principle Research by sociolinguists into how bilingual people use their languages concludes that bilinguals don't develop their two languages equally. During communicative interac- tions bilinguals do not use their two languages in a balanced way. Instead, as Grosjean states: bilinguals usually acquire and use their languages for different purposes, in different domains of life, with different people. Different aspects of life often require different languages. (2010, 29) a Grosjean refers to this phenomenon as the complementarity principle. Rather than developing equal abilities in each language, bilinguals develop the language they need to communicate with different people in different settings when discussing different subjects. Each language complements the other. David's proficiency in Spanish and English provides a good example of the comple- mentarity principle. When he spent a year at a university in Mrida, Venezuela, David could carry on a conversation in Spanish with colleagues at the university, go shop- ping, and read articles on topics for which he had some background. He felt as though his Spanish was improving until he took his car to a shop for a mechanical problem. Mrida is in the Andes, and most driving involves going to higher or lower elevations. From David's house to the university across town, there was a change in elevation of two thousand feet. Friends had advised David to have his car's brake pads changed every six months and to have the shock absorbers checked as well since some of the roads were rough. David does not have a strong background in car mechanics, but he felt confident that he could communicate what he needed at a local garage. However, when he got there, the mechanic was confused about what David wanted, and David realized he did not have the vocabulary or syntax to explain what he needed to have done. His Spanish proficiency was not as good as his English in this context, and although he finally communicated what he wanted done, he had to use gestures and point to parts of the car. Fortunately, this worked, but it helped David see that he was certainly not a balanced bilingual. Grosjean concludes his discussion of the complementarity principle by stating that most bilinguals simply do not need to be equally competent in all their languages. The level of fluency they attain in a language . . . will depend on their need for that language and will be domain specific (2010, 21). Because bilinguals develop their two languages for use in different domains, very few are completely balanced. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Consider how language is used for teaching and assessing emergent bilinguals. Is the goal of your school's programs for emergent bilinguals that they become balanced? Share with a partner. Monoglossic and Heteroglossic Views of Bilingualism Current research has shown that proficient bilingual and biliterate people are not balanced. The misconception of balanced bilinguals comes from what Garca (2009) refers to as a monoglossic view of bilingualism. Monoglossic comes from the prefix mono, meaning one, and the root glossic, meaning tongue or voice. Monoglossic views of bilinguals and bilingual education consider that each lan- guage is one separate entity. Garca considers programs such as early-exit bilingual and ESL programs to be monoglossic because students often enter school speaking their home language, but in the process of acquiring English, many fail to develop, or even lose, that language. As a result, English learners may begin and end their programs as monolinguals. Even in effective bilingual programs, language instruction is often organized in a way that keeps the two languages separate. This approach is based on the monoglossic view because the goal of these programs is to develop a person who is the equivalent of two monolinguals. During instruction and assessment, the two languages are kept separate. As Garca observes, bilinguals are expected to be and do with each of their languages the same thing as monolinguals (2009, 52). Students are expected to per- form like English monolinguals during English time and like Spanish monolinguals during Spanish time. Monoglossic views of bilinguals and of programs for emergent bilinguals have predominated in schools. The twentieth-century views that bilinguals are two monolinguals in one person and that the goal of bilingual education is to produce balanced bilinguals have led to practices that Cummins (2007) argues are based on misconceptions. One of these mis- conceptions applies specifically to dual language bilingual programs. Cummins refers to this as the two solitudes assumption. The misconception is that in bilingual programs the two languages should be kept rigidly separated. Cummins points out: This assumption was initially articulated by Lambert and Tucker (1972) in the context of the St. Lambert French immersion program evaluation and since that time has become axiomatic in the implementation of second language immersion and most dual language programs. (233) The practice of keeping the two languages strictly separated is based on assump- tions rather than on empirical research. In al language bilingual programs where the two languages are strictly separated, students are treated like two monolinguals. For example, in a Spanish-English dual language program during English time, all students are taught like monolingual English speakers and during Spanish time they are treated like monolingual Spanish speakers. Although the teachers make the input in English or Spanish comprehensible, there is no recourse to using students' home languages as a resource. The practice of separating the two languages developed to ensure that enough time was allocated to each language for students to acquire the language. Without sufficient exposure to a language, it is not possible to develop proficiency in the language. In some cases, even when bilingual programs allocated a specific time for each language, some teachers translated each thing they said to help students understand a lesson. This practice, called concurrent translation, is not effective because when students know that the teacher will translate, they ignore the input given in the target language. So a Hmong speaker in a Hmong-English program might ignore the English, and an English speaker might ignore the Hmong. Strict separation of languages in many programs developed to avoid concurrent translation and to ensure that administrators could monitor language use since they would know what language to expect during an in-class evaluation. An example of how concurrent translation works comes from driving a car. The speedometer shows both miles and kilometers, and drivers simply ignore the system that they are not familiar with. Drivers in Mexico would gauge their speed in kilome- ters per hour and most drivers in the United States would focus on miles per hour. In the same way, some banks show the temperature in both centigrade and Fahrenheit, and again people pay attention to the system they are familiar with. If teachers trans- late everything into emergent bilinguals' home languages, the students may not try to make sense of the new language they are trying to acquire. In many dual language bilingual programs there is one teacher for each language; in others, different subjects are taught in each of the languages. For example, math might be in English and science in Spanish. In other programs the languages are distributed by timemornings in English and afternoons in Spanish. Still other programs alternate languages on a daily or weekly basis. In all cases, there are specific times, subjects, or teachers for each language with no overlap. Many effective practices are excluded when instruction is limited to one language at a time. For example, having students access cognates depends on using both lan- guages simultaneously. When the languages are not separated, students can carry out linguistic investigations and build metalinguistic awareness by comparing and con- trasting languages. For example, students could compare and contrast the structure of possessives in English and Spanish sentences. Cummins explains his support of these types of activities as he writes, It does seem reasonable to create largely separate spaces for each language within a bilingual or immersion program. However, there are also compelling arguments to be made for creating a shared or interdependent space for the promotion of language awareness and cross-language cognitive processing. The reality is that students are making cross-linguistic connections throughout the course of their learning in a bilingual or immersion program, so why not nurture this learning strategy and help students to apply it more efficiently? (2007, 229) Cummins points out that there is theoretical support for using both languages for instruction. Research has shown that new knowledge is built on existing knowledge, and if that knowledge was developed in the home language, it can best be accessed through the home language (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). In addition, literacy skills are interdependent, so teaching should fa- cilitate cross-language transfer. Cummins concludes his discussion of the two solitudes misconception by stating, the empirical evidence is consistent both with an emphasis on extensive communicative interaction in the TL [target language) (ideally in both oral and written modes) and the utility of students' home language as a cognitive tool in learning the TL (2007, 22627). Instead of operating from a monoglossic perspective, Garca argues, educators should take a heteroglossic perspective. The prefix hetero comes from the Greek mean- ing other. The term heteroglossic comes from the writing of the Russian literary critic Bakhtin (1981). He used the term to refer to the multiple or other voices that coexist within a novel, the voices of the characters and of the narrator. Garca uses the term to refer to the two or more languages that exist in the mind of a bilingual speaker. As Bialystok points out, the two or more languages are always active in the mind of a bi- lingual. These languages cannot be strictly separated because they are always present. This view is a better reflection of how bilinguals really use their languages. Garca argues that strict separation of languages is not natural. It does not reflect the custom- ary use of language by bilinguals. Instead of keeping languages apart, bilingual pro- grams in schools should draw on all the linguistic resources of emergent bilinguals. Garca refers to bilingual programs based on a heteroglossic view of emergent bilin- guals as dynamic. For Garca and her colleagues (Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer 2017), dynamic bilingualism better describes bilingualism in a globalized society. From a perspective of dynamic bilingualism, bilinguals and multilinguals use their languages for a variety of purposes and in a variety of settings. They are more or less proficient in the different contexts where they use the languages and are more or less proficient in different modalities (visual, print, and sound). Garca explains that dynamic bilingual- ism is consistent with the definition of plurilingualism given by the Language Policy Division of the Council of Europe: the ability to use several languages to varying degrees and for distinct purposes (Garca 2009, 54). She challenges educators to look at bilingual education in a new way, taking a heteroglossic view of dynamic bilingual- ism. She argues that this new view of bilinguals and of bilingual education is needed because bilingual education in the United States has been built on the misguided monoglossic view. REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK Do the programs for emergent bilinguals at your school have a monoglossic view or a heteroglossic view of bilingualism? Consider how the home language is used in ESL or bilingual classes for emergent bilinguals. Share with others at your school. Research on Bilingualism Two hypotheses based on research Cummins (1979) conducted provide support for viewing bilingual students holistically and as learners drawing on both of their languages: the interdependence hypothesis and the common underlying proficiency (CUP) hypothesis. A seemingly commonsense assumption that is made in teaching emergent bilin- guals in many places is that more English equals more English. This idea seems logi- cal. It is a variation of the time-on-task assumption that claims the more time spent on a task, the greater the proficiency a student develops. In this case, the assumption is that the more time students spend being instructed in English, the more proficient they will become in English. However, Cummins explains that this seemingly logical assumption fails to recognize that languages are interdependent, and the development of the home language has a positive effect on the development of an additional lan- guage. He states: To the extent that instruction in Ly is effective in promoting proficiency in Lx, transfer of this proficiency to Ly will occur provided there is adequate exposure to Ly (either in school or the environment) and adequate motivation to learn Ly. (1979, 29) In other words, when students are taught in and develop proficiency in their home language, Ly, that proficiency will transfer to an additional language, Ly, assuming they are given enough exposure to the second language and are motivated to learn it. Cummins explains that the reason proficiency transfers from one language to another is that a common proficiency underlies an emergent bilingual's languages. Because of this common underlying proficiency there is an interdependence of con- cepts, skills, and linguistic knowledge that makes transfer possible (1979, 191). According to Cummins, the common underlying proficiency can be thought of as a central processing system comprising (1) attributes of the individuals such as cognitive and linguistic abilities (memory, auditory discrimination, abstract rea- soning, etc.) and (2) specific conceptual and linguistic knowledge derived from experience and learning (vocabulary knowledge) (2000, 191). As a result of this in- terdependence, an emergent bilingual can draw on cognitive and linguistic abilities and skills acquired in the home language to develop literacy and content knowledge in an additional language. For example, if the home language shares features, such as cognates or syntactic structures, with English, those components of the home language can transfer to English when teachers use strategies to bridge between the two languages. Spanish and English share many cognates since the two languages both include many Latinate words. Linguists estimate that 30 to 40 percent of English words have Spanish cognates. Teachers can create cognate word walls to help students become more aware of the cognates. In addition, a good strategy for Spanish speakers read- ing in English is to check to see if an unknown English word looks and sounds like a word in Spanish There are many ways that teachers can use cognates in teaching in either bilingual or ESL classes. They can put students in pairs where both students are at least some- what proficient in Spanish. Students can look at key vocabulary in English around a topic and try to identify cognates that exist in Spanish. So students studying zoo animals might identify giraffe and jirafa, hippopotamus and hipoptomo, and tiger and tigre. Students working virtually could help each other either though an online conversation or through texts as they look for cognates. If students are reading a text in math, sci- ence, or social studies, there are many opportunities to work together to find Spanish- English cognates as they read. Once they find cognates, they can add them to a classroom cognate wall or contribute to a shared Google document if working on- line. Alternatively, the teacher can pick out scientific terms or complex social studies vocabulary from English textbooks and challenge students who speak Spanish or who are learning Spanish to identify the Spanish equivalents. Cummins' CUP hypothesis can help account for the difference in academic perfor- mance of students with similar levels of English proficiency. Because content knowl- edge and literacy skills transfer, a fourth-grade emergent bilingual who can read and write at grade level in his home language and who has developed grade-level content knowledge in that language will succeed academically in English much more quickly than another fourth grader who has developed only a low level of home language literacy and lacks academic content knowledge, even if they are both classified as low intermediates in English proficiency. Cummins (2000) contrasts the idea of a common underlying proficiency with that of a separate underlying proficiency (SUP). Those who hold to the SUP theory must believe that what we learn in one language goes to one part of our brain and cannot be accessed when we are learning and speaking another language. This must be what opponents of bilingual education believe when they say that students learning in their home language are wasting time. They should be learning only in English. However, students in programs that build their home language as they acquire English develop higher levels of academic proficiency than students schooled only in English. Cummins uses the image of an iceberg with two peaks to illustrate his CUP hypothesis. The two peaks of the iceberg that are above the waterline represent the surface features (the sounds or writing) of the two languages. The part of the iceberg below the surface of the water where the languages overlap represents the knowledge and skills that are common to the two languages and can transfer from one language to the other. Figure 51 is a representation of the iceberg with two peaks. Students who have more schooling in their home language can draw upon that knowledge as they are acquiring an additional language. Over time students with greater total underlying proficiency can do well academically in English. Students without the underlying academic proficiency in their home language, however, struggle because they have less to draw upon as they are learning academic content and literacy in a new language. L1 L2 common underlying proficiency Separate languages have overlapping elements. Bilinguals have a common underlying proficiency. Figure 5-1 Dual Iceberg Model In Chapter 2 we discussed Tou, a long-term English learner. Although he entered school a dominant Hmong speaker, he never developed literacy in his home language. He had conversational English but struggled academically. Long-term ELs studying in this country do not develop academic language or grade-level proficiency in literacy in their home language. They struggle with understanding the curriculum taught all in English and get farther and farther behind. Schooling in the home country helps immigrants when they come to live in this country. Mary's husband, Francisco, came to the United States at age fourteen with no English, but he liked school in El Salvador and read every book he could get his hands on. His schooling in this country was all in English. Although it took him time to do well in school, his eventual success can be linked to the transfer of literacy skills and his knowledge of math, science, and history in Spanish, which supported his under- standing of instruction in English. Translanguaging Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer (2017) take Cummins' concept of a common underlying proficiency a step further. Instead of viewing the bilingual as having two separate languages with a common underlying proficiency, they argue that bilinguals a have one complex linguistic system that has features of two or more languages, which they refer to as a linguistic repertoire. (See Figure 52.) Garca and her colleagues (2017) explain that the linguistic repertoire is a set of linguistic features that people draw on to communicate. Bilinguals and multilinguals have linguistic repertoires with features that are used in more than one language. Linguistic features include phonemes, morphemes, syntactic structures, and so on, that constitute a language. Some features, such as the order of words in a sentence (subject, verb, object) or certain phonemes, such as /d/, might be the same in some languages and different in other languages. Emergent bilinguals can draw on the features of both languages, features that are unique to either language and features that are common to two languages as they communicate. In the process of making meaning, bilinguals draw on their full linguistic reper- toire in a process Garca and Wei (2014) refer to as translanguaging. The term trans- languaging comes from Williams (1996), a Welsh educator, who was teaching Welsh to English-speaking students in Wales as part of an effort to revitalize the language. In his teaching, Williams had students read or listen in one language and then write or speak in the other. He referred to this process as translanguaging. Students went across (trans) languages as they studied using Welsh and English. Garca (2009) defines translanguaging as the typical way bilinguals use language as they communicate both in and out of school. She explains, Translanguagings are Spanish English FFFnFF, FFnFF, F, Fm Fm nnnnnn n'n'n'n'n'n n'n'n'n'n'n'n'n'n'n'n FnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFnFn! Fm n Linguistic Repertoire Figure 5-2 Linguistic Repertoire Adapted from Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer (2017) the multiple discursive practices in which bilinguals engage in order to make sense of their bilingual worlds (45). That is, they draw on all their language resources to communicate effectively. Similarly, Baker and Wright point out that children pragmatically use both their languages in order to maximize understanding and performance in any lesson (2017, 280). They go on to say, Translanguaging is the process of making meaning, shaping experiences, understandings, and knowledge through the use of two languages (280). In his review of the definitions of translanguaging, Cummins concludes: Translanguaging is clearly non-problematic when viewed as a descriptive concept to refer to (a) typical patterns of interpersonal interaction among multilingual individuals where participants draw on their individual and shared linguistic repertoires to communicate without regard to conventional language boundaries, and (b) classroom interactions that draw on students' multilingual repertoires in addition to the official or dominant language of instruction. (forthcoming, 2) These different researchers all conclude that translanguaging is a typical way that bilinguals communicate and that it can be used in bilingual classes to affirm students' bilingual identities, build metalinguistic understanding, and scaffold instruction by strategically drawing on students' home languages while still allocating the major por- tion of the time for each of the languages of instruction. The key is to use the home language strategically and not simply revert to concurrent translation. An effective approach to strategic language allocation in dual language is to plan at both a macro level and a micro level. At the macro level, teachers should use the target language most of the time during a lesson. For example, in a Spanish-English dual language class that alternates the two languages each day, on an English day, English would be used most of the time. This is the macro level. However, at the micro level, teachers can use the home language strategically. For example, the teacher could use Spanish to provide a brief preview of the lesson or to compare how to form the possessive in the two languages. Figure 53 shows how teachers can allocate languages at the macro and micro levels during instruction (Ebe, personal communication). Whether bilinguals have a single linguistic system, as Garca argues, or two over- lapping systems with a common underlying component, as Cummins contends, there is an agreement that translanguaging serves an important role in educating emergent bilinguals. See Cummins (2017, forthcoming) and Otheguy, Garca, and Reid (2015, 2018) for further discussion of this question. Alternation at the Macro Level Alternation at the Micro Level Dedicated time for each language Translanguaging spaces within the dedicated Spanish or English time by day: Spanish one day, English the next by time: Spanish in AM, English in PM .by subject matter: math in English and social studies in Spanish flexible language use by teachers and students strategic, scaffolded, differentiated preview, view, review . . Program level Classroom or online Figure 5-3 Language Allocation at the Macro and Micro Levels Adapted from Ebe REFLECT OR TURN AND TALK What are the implications of the research on translanguaging by Cummins and Garca for teaching emergent bilinguals? How is this reflected in your school? Share your reflections with others at your school if possible. Bilingualism Is Dynamic Garca (2009) explains that bilinguals don't simply add a new language to an existing language. Instead, they incorporate the features of the new language into an inte- grated, dynamic system. As Cummins observes, Garca uses the term translanguaging to describe the dynamic heteroglossic integrated linguistic practices of multilingual individuals (forthcoming, 1). Teachers can implement translanguaging strategies that use the entire linguistic repertoire of bilingual students flexibly in order to teach both rigorous content and language for academic use. The term dynamic bilingualism reflects the fact that the languages of an emergent bilingual are always active in the brain, and bilinguals draw on all their language resources as they communicate. Garca and Kleyn explain: a Dynamic bilingualism goes beyond the notion of additive bilingualism because it does not simply refer to the addition of a separate set of language features, but acknowledges that the linguistic features and practices of bilinguals form a unitary linguistic system that interacts in dynamic ways. (2016, 16) Dynamic bilingualism is the appropriate term for bilingualism in a globalized soci- ety. From a dynamic bilingualism perspective, bilinguals and multilinguals use their languages for a variety of purposes and in a variety of settings. They are more or less proficient in the various contexts where they use the languages and are more or less proficient in different modalities (visual, print, and sound). Their languages continu- ally develop as they use each language in a variety of settings. Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer explain that in a classroom with emergent bilin- guals there is a translanguaging corriente (current in a stream): We use the metaphor of the translanguaging corriente to refer to the current or flow of students' dynamic bilingualism that runs through our classrooms and schools. Bilingual students make use of the translanguaging corriente either covertly or overtly to learn content and language in school and to make sense of their complex worlds and identities. (2017, 21) Picture this corriente as a constant stream above your students' heads or under their feet. In this corriente, the language knowledge in their linguistic repertoire is flowing all the time. So, if the teacher is reading and talking about a novel in English with the class, emergent bilinguals can draw upon their other language or languages to make sense of what the teacher is reading and discussing. However, the teacher has to strategically invite students to access their full linguis- tic repertoires. The teacher might have students turn and talk about the characters in the novel or the setting or the conflict using their home languages if they wish and then report back in English. The teacher might direct students to do a quickwrite in their home language or English listing key events in the novel so far and have the whole class brainstorm together a list on the whiteboard. Each of these activities draws upon knowledge students have in their home language, that corriente, and gives them more access to the curriculum taught in English. Garca, Ibarra Johnson, and Seltzer state that teachers can use the translanguaging corriente to 1. Support students as they engage with and comprehend complex content and texts 2. Provide opportunities for students to develop linguistic practices for academic contexts 3. Make space for students' bilingualism and ways of knowing 4. Support students' socioemotional development and bilingual identities. (2017, ix) Translanguaging Is Not Code-Switching Until Garca and others began using the term translanguaging to describe the language practices in bilingual communities, researchers referred to the process as code mixing or code-switching. Code here refers to a language. A language can be seen as a system for encoding meanings. Linguists used code-switching to describe the process of switch- ing from one language to another, sometimes in the same sentence. For example, a Spanish-English bilingual might say, I haven't eaten since lunch, and ahora tengo hambre [now I'm hungry]. Linguists and sociolinguists have studied code-switching as a process of switch- ing from one language to another. Grosjean writes, Code-switching is also used as a communicative or social strategy to show speaker involvement, mark group iden- tity, exclude someone, raise one's status, show expertise, and so on (2010, 5455). In South Texas along the border, bilinguals often code-switch to identify themselves as part of the Mexican American community. After reading about and discussing translanguaging, two of our graduate students studying bilingual education compiled a list of reasons people code-switch with examples from their own experiences (see Figure 54). Although linguists have found that bilinguals draw on two languages as they com- municate for a number of different reasons, code-switching has a negative connotation for many people. Some bilinguals we have worked with have apologized for mixing two languages or using Spanglish. Some people assume that bilinguals have to code- switch because they are deficient in one or both of their languages. Garca points out that code-switching is a way to describe the language practices of bilinguals from an external point of view. Someone observing two bilinguals might Purpose English-Spanish Example 1. To emphasize a particular point in conversation Andale, go do your homework. 2. To substitute an unknown word in another language Voy a hacer mi trabajo en la laptop. La teacher nos dejo mucha tarea. 3. To express a concept that has no equivalent in the culture of the other language There was a piata at the party. That lunch looks good! Bon apptit. 4. To reinforce a request Get to workpnganse a trabajar. Come, come! Crrele! 5. To clarify a point Animals adapt to their environment-los animals se adaptan a su medio ambiente, es decir, se acostumbran al lugar donde viven. For this exercise you are going to do three circles, tres crculos. Come here, mijito. 6. To express identity or communicate friendship or family bonding As es, amor, good job! 7. To report a conversation held previously Holding a conversation in English, but retelling it to someone else in Spanish: When he came into the room, we all yelled, Feliz cumpleaos! 8. To interject into a conversation If two people are having a conversation in Spanish, and you interject by saying, Excuse me." 9. To indicate a change of attitude or relationship People code-switch when there is less social distance, more solidarity, and growing rapport: Angela told me, "Dra. Freeman, Ud. Me conoce. No soy as." 10. To exclude people from a conversation Grandparents speak in a language their grandson does not understand. 11. To refer to certain topics, such as money Fui al dealership y el car costaba five thousand dollars. Figure 5-4 Reasons for Code-Switching conclude that they were switching between languages. However, from the bilingual person's own viewpoint, the use of the two languages is simply a way of using all their language resources to communicate. From a holistic view of a bilingual as a person with one complex linguistic system, there is no switching between codes of separate languages. Instead, the bilingual is drawing on features of one complex linguistic sys- tem to communicate effectively. Garca and Wei state: Translanguaging differs from the notion of code-switching in that it refers not simply to a shift or shuttle between two languages, but to the speakers' construction and use of original and complex interrelated discursive practices that cannot be easily assigned to one or another traditional definition of a language, but that make up the speakers' complete language repertoire. (2014, 22) From this perspective, drawing on words and phrases from both languages allows a bilingual to communicate more effectively in the same way that having a large vo- cabulary in one language allows a person to express themselves more fully. Bilinguals translanguage in certain contexts. They would draw on features of two languages only when communicating with another bilingual. In the same way that speakers shift from formal to informal registers depending on whom they are talking with and the context, bilinguals shift languages to communicate effectively in differ- ent situations with different people. They do this automatically in order to use their language resources effectively. Translanguaging Strategies in Schools and During Remote Teaching a In bilingual and ESL (or ELD) programs that take a view of dynamic bilingualism, teachers use translanguaging strategies to affirm students' bilingual identities, to help them build metalinguistic awareness, and to promote the development of their aca- demic language proficiency and their academic content knowledge. Teachers do this by using students' home languages strategically during both in-classroom and remote teaching. As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, many schools have adopted ways to combine face-to-face and remote teaching. In the following sections we provide examples of translanguaging strategies teachers are using. We have written about translanguaging strategies in several publications (see Freeman, Soto, and Freeman 2016; Freeman et al. 2016; Freeman, Freeman, and Mercuri 2018; Soto, Freeman, and Freeman 2020). Affirming Students' Bilingual Identity When teachers use strategies that draw on all students' home languages, they tap into the translanguaging corriente and affirm students' bilingual identity. They ensure that the school's linguistic ecology reflects the languages and cultures of all the students in the school by including those languages in murals, signs, and student work in hallways and classrooms as well as in correspondence with parents. School libraries include books and other resources that reflect students' languages and cultures. Teachers also incorporate activiti that draw on and showcase students' languages, ch as posting bilingual and multilingual word walls. They include routines such as turn-and-talks where students can use their home language or English. All of these practices affirm students' languages and cultures and promote linguistic and cultural equity. Mary and Elizabeth, two professors in a teacher education course, wanted to help their teacher candidates design activities to develop their own students' cul- tural identities. First, they organized students into groups. Each group represented as great a variety of cultures as possible so that different voices could be heard during group discussions. Some of the students were white with a variety of backgrounds, others were Hmong, and the majority were Latinx. First Mary and Elizabeth asked the groups to come up with a definition of culture. They asked them not to look up a definition, but to consider their own experiences and ideas. Some of the groups defined culture as their home language and ways they did things at holidays. Others mentioned typical cultural dishes and strict rules. Still others mentioned expectations like going to college or being married in the church. The groups shared their defini- tions with their classmates. After considering the different definitions of culture, each group made a mandala. The groups had a template to complete, and each student in the group chose different aspects of their culture and represented it on the outside circle of the group mandala. After sharing the drawings, the group decided on what all members of the group had in common and wrote that in the middle. For example, one group with two students of Mexican background and one with Hmong background found they had a lot in common, including food, religion, sports, mily, lan age, and celebrations (see Figure 55). Another group representing Hmong and Mexican cultures chose just one commonality, family (see Figure 56). ThWWho VGVPV En HONN bird ner Soods Sharing. family, 10:09 frerkurse Fungry? less tiems. Hari WORX so Figure 5-5. Cultural Mandala 1 on the sum INANCY LOS 007 901N hartworking v Figure 5-6 Cultural Mandala 2 Then the teachers assigned a second activity to make the students think even more deeply on the topic of culture: the culture Venn diagram. They gave students the fol- lowing directions: Partner up with someone in your group. Each of you should pick a shape that represents your culture. Draw your shapes overlapping (as in a traditional Venn diagram). On the outside sections, write characteristics of your culture. On the overlap, write about how your cultures are similar. Each pair of students used a different piece of poster paper and worked to think of something that represented their culture. In the cultural Venn diagram shown in Fig- ure 57, Jessica drew a Hmong drum often used in festivals and funerals in traditional Hmong culture and Gregoria drew a nopal cactus, symbolic of both arid landscapes in Mexico and the nopal leaves and fruit, which are used for different purposes. Within each symbol the students wrote reflections of their own culture. Then they wrote what they had in common in the overlapping section. > MEXICA |-Running TUNAS "NOPALES -Hmong from oroville -Eggrolls 7Shamanism Flaab Springrolls Vavos s bilingual MAMEY Swin nitting Eachers WALKING Family's BURRITOS Us Rico 40 future Solyom MARIACHI TACA SELEPAS Jessica