Question: please answer this following questions answer as soon as possible within half hour 1-Introduction 2- The identification of the problem 3- External Analysis 4- Internal

please answer this following questions answer as soon as possible within half hour

1-Introduction

2- The identification of the problem

3- External Analysis

4- Internal Analysis

5- Sources of problem

6- strategic options

7- Recommendations how to solved the problems

please answer this as soon as possible please answer this within 30 minutes

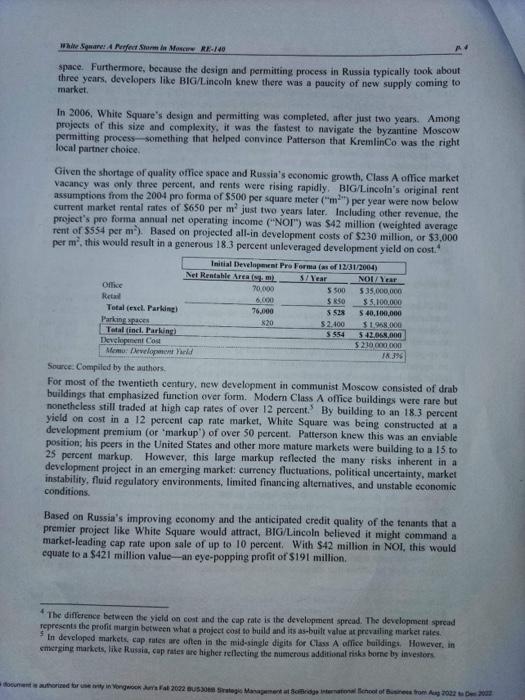

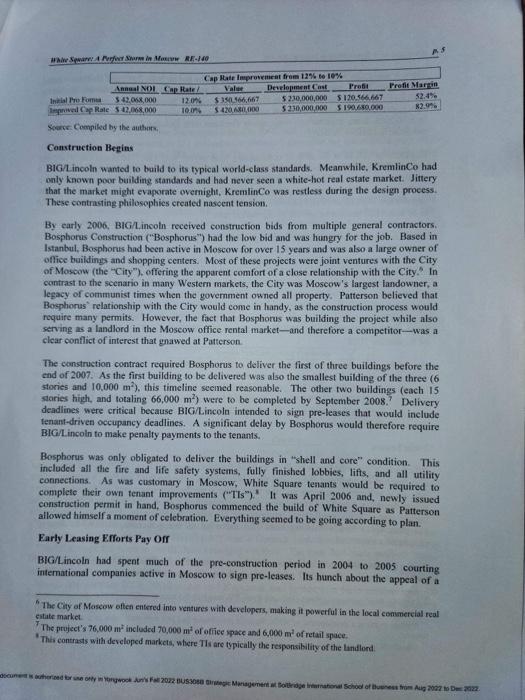

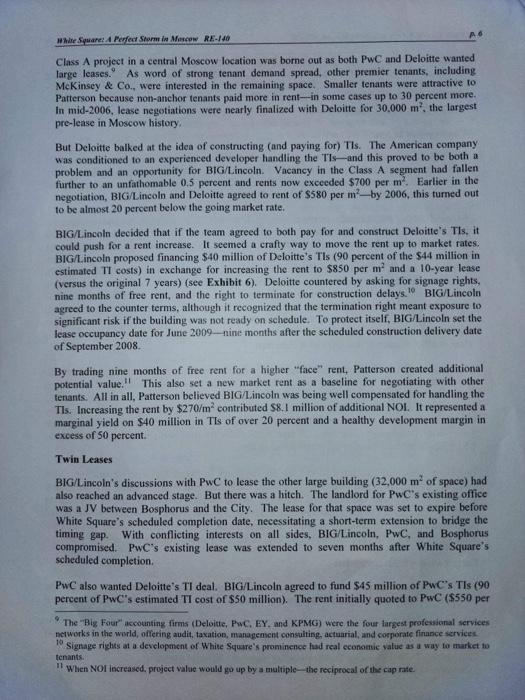

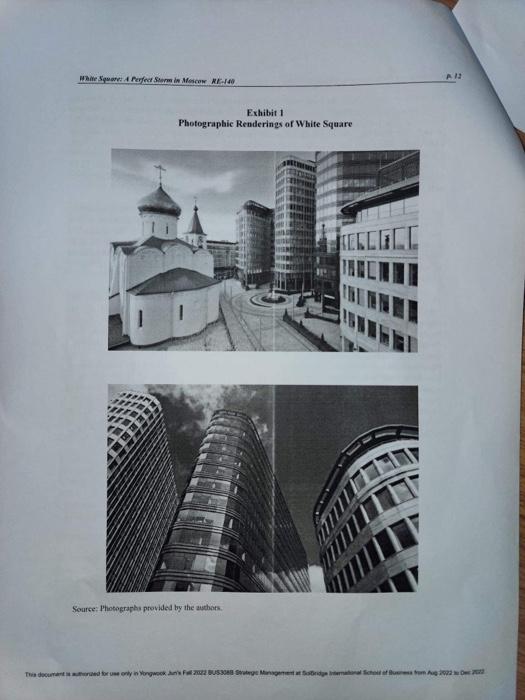

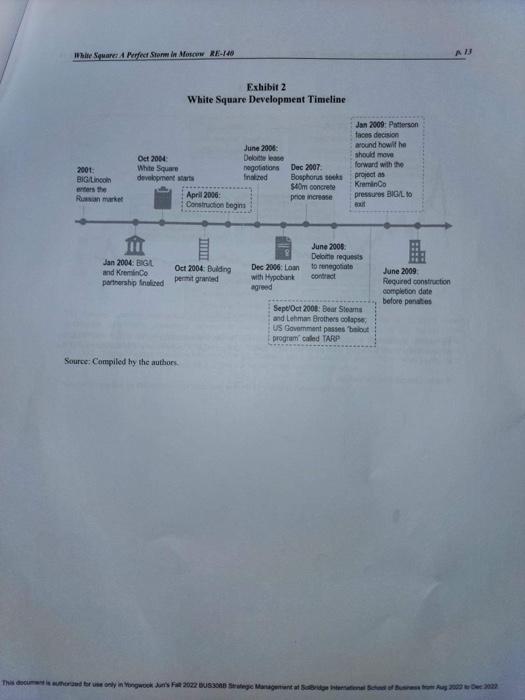

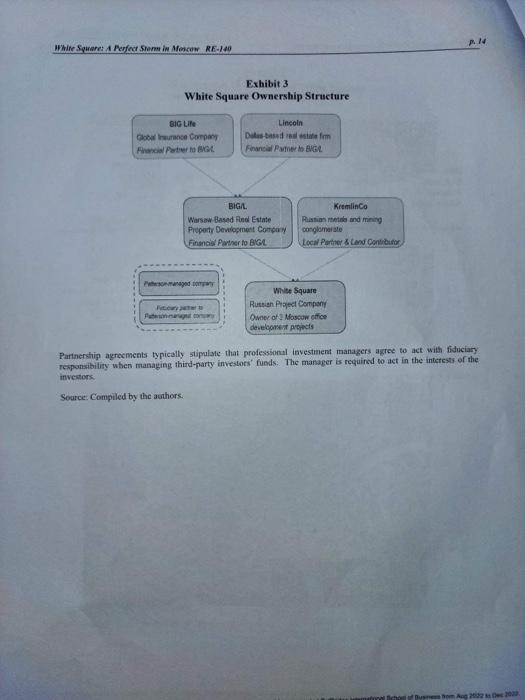

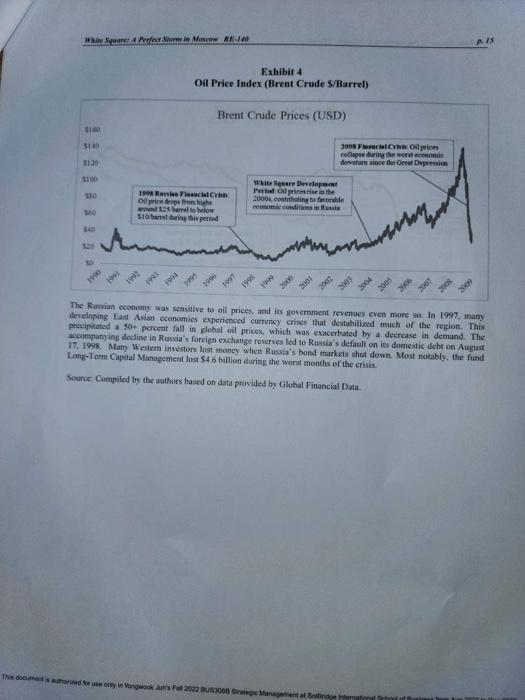

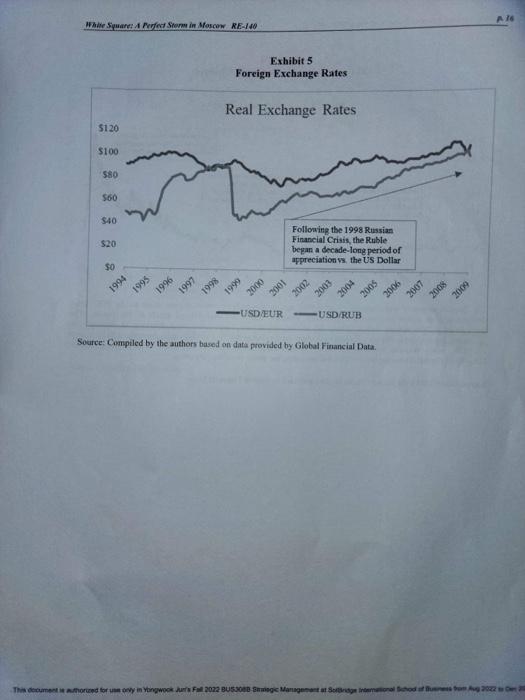

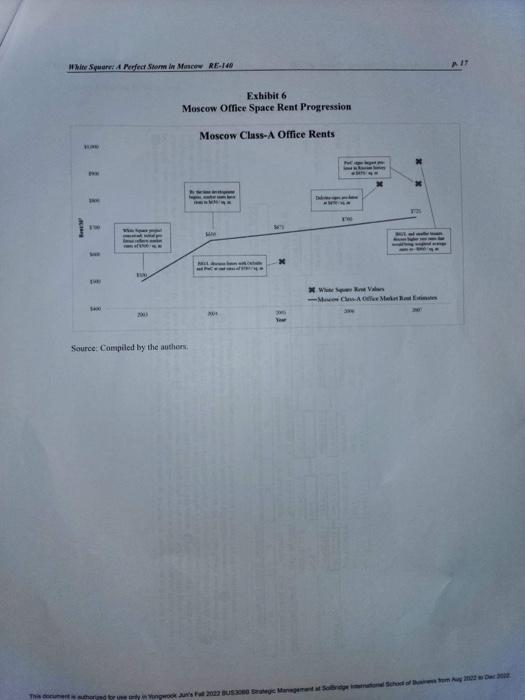

WHITE SQUARE: A PERFECT STORM IN MOSCOW - Vlaxlimir Putin. Fresident of Ressux. It was carly 2009, and Brian Patterson sat erestfallen in his Moscov office as the world cconomy unraveled in the wake of ahe global fianancial crisis ("GFC"). Ife was under heavy pressure from KremlinCo, his local Russian partner, to aell White Square as sood as possible. White Square was a premier office project that Patterson's fimm, BIG.Lincoln, was developing In Moscow (see Exhibit 1) Alter six years, the developenent was nearing completion. However, KremlinCo was reeling and necded liquidity. If consummated, a sale would nonetize the project's 3100 million of invested equity plus a small profit. An immensely dispiriting outcome to. Patterson, this wns a fraction of the over $475 million in profit that looked so achicvable only a short time earlier. If Patterson pressed on, the project faced a risky future and the real possibility of a loss of his parincrs' $100 million of cquity fincluding land that KremlinCo had contributed). In the midst of his angst. Patterson tried to comprehend how things had gone so wrong for White Square, Entil recently, the 76,000 square-meter project ( 818,000 square fect) had all the right elements-a premicr location, world-class tenants, a well-capatalized investor, financing froen a fop-tier German bank, the most experienced contractor in Moscow, and a reputable local partner. Just a few noniths earlier, the pro forma reflected a jaw-dropping $475 million profit on $3.5 million in total project costs. Pafterson's dilemuma comprived two very different types of challenges: 1) managing the projectlevel problems that were expected for at development of this size and complexity, and 2) perhaps more vexing, navigating antong the divergent interests of his capital partners. ISinwon Sbwast, "The World Necocding to Vladimir Putin, Time, \$cpocnher 16, 2013, Cody Finana (MBA 19), Inan Paichon (MBA 39), and Lecturer Chris Mahowald (MiEA. 89) prepared this case as the bais for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handing of an adminiatrative situation. Hhine Souarei 4 Pegfert Siform in. Masicor RE-lde Project Development Problems Patterson's problems were numerous Construction was behind schedule and the contractor was demanding a massive $40 million price increase-the result of the contractor mismanaging its own contractual risk and getting jammed by the local concrete supplier. The anchor tenant only wanted half its lease square footage amid a once white-hot Moscow office market that was now in free fall. And the project's German lender was looking for a reason to call the loan and exit Russia. Patterson couldn't escape the ominous macrocconomic headlines from around the world: Yes, the sky was falling. He was facing an uphill battle, even by the exacting burdens expected of a developer. If he couldn't solve these problems, he would simply have to sell. Divergent Interests Among the Partners While Patterson was busy addressing project-level problems, KremlinCo had dredged up a purchase offer from a Kazakh buyer for invested cost ( $100 million) plus $25 million of profit. On the heels of a pro forma that reflected a project value of $790 million and profit of $475 million, this would mean abandoning an extraordinary potential return. When White Square was originally conceived, Patterson had convinced KremlinCo to contribute the land for a one-third ownership interest in the project. This simplified the negotiation over land value and oriented KremlinCo's focus toward the ultimate value of the project by partnering with BIG/Lincoln-a firm with real development expertise and deep-pocketed financial backing. Complicating things, the principal of KremlinCo had important relationships in Moscow. As a Moscow outsider, Patterson felt these relationships were critical to his role as developer. Separately. Patterson's capital partner BIG Life, was grappling with its own GFC-related finencial problems. The sale to the Kazakh investor would return a modest profit alongside BIG Life's $62 million of cash equity invested in White Square and help shore up its own rapidly deteriorating balance sheet. Valuations across the BIG Life global portfolio were plummeting and there was no telling when the bleeding would stop. But the old axiom remained true-cash was king _ and BIG Life knew it would take more of it to work through the GFC. Patterson, on the other hand, was heavily incentivized to proceed. Although he had not invested cash in the deal, Patterson had committed to fund project cost overruns if necessary and therefore had something to lose. But with a healthy share of the profits, he stood to make a sizeable personal fortune based on the pro forma of just a few months ago. After many years of laying the groundwork for the project and establishing his reputation as a developer in Russia, Patterson found the thought of giving up now nauseating. However, he had a fiduciary responsibility to act in the best interests of his partners. How could he balance these competing interests while keeping his own vision alive after six long years of work? (See Exhibit 2 for a timeline of the White Square development project.) From TExASto REssia Patterson, a country boy from Texas, had moved to Warsaw in 1992 as a recent Stanford GSB graduate to pursue adventure and to set up his own property development company, By 2001, he was building five projects across Poland with a total cost of over $250 million. He was running BIG/Lincoln, a Warsaw-based real estate company, which was developing projects to Company (see Exhibit 3 for an overview of the partnership structure). BIG Life, a New Yorkbased global insurance company with $30 billion invested in real estate, was the "money partner." BIG Life was active in 50 countries and expanding. Lincoln Property Company, a real estate developer based in Dallas, was one of the largest real estate firms in the United States with projects across North America and Europe. Lincoin was the "development partner"-Ied by Patterson-for the BIG/ incoln JV. The combination of Patterson and two premier firms made a strong team for developing in emerging markets. More than a decade after the fall of communism, the Russian economy was growing rapidly, and the country welcomed forcign investors. The 1998 Russian financial crisis had dealt a major sethack to the economy, but BIG Life now reasoned that the worst was behind them (see Exhibits 4 and 5). While there were still major challenges to doing business in Russia, BIG Life-sensed opportunity and asked Lincoln and Patterson to expand BIG/Lincoln's footprint there. Finding a Partner BIG/ Lincoln's first order of business was to find a Russian development partner to navigate local rules, regulations, and laws-which could be idiosyneratic and difficult for outsiders to understand. Moscow was new territory to Patterson, and he knew he needed a local on his side to avoid the plague of costly mistakes that often afllict investors entering a new market. A deep-pocketed capital source like BIG Life and an experienced developer like Lincoln made for an appealing combination to prospective local partners. After a thorough courting process, BIG/ Lincoln settled on KremlinCo, a Russian metals and mining conglomerate that had deep relationships in government and previous real estate experience. KremlinCo owned some land that seemed like an ideal site for development. Patterson valued KremlinCo's size and government connections-attributes he believed would be helpful for future projects. BIGILincoln and KremlinCo drafted a business plan and a development agreement. The nascent partnership began working on the development of its first venture-a three-building office complex that would come to be known as White Square. A 'WHITE' HoT MARKET Launching the development of White Square in late 2004 seemed opportune. Russia had six years of strong economic growth under its belt, an investment-grade sovereign debt rating, and it was pursuing membership in the WTO. 2 Although Moscow had a dearth of sophisticated real estate developers, industry analysts were comparing its real estate market to London and Paris, the most prominent markets in Europe. A study in Emerging Trends in Real Estate ranked Moscow the best market on the continent.' And it was a Landlord's market: There were so few quality office buildings that the existing stock was subject to competition among tenants seeking "The mission of the WTO, or World Trade Organization. was to "ensure that trade flows smoothly. predictably and (October 1, 2018). While Souarer 4 Porfect. Shirm in Moserw RR-l40 nd space. Furthermore, because the design and permitting process in Russia typically took about three years, developers. like BIG/Lincoln knew there was a pascity of new supply coming to market. In 2006, White Square's design and permitting was completed, after just two years. Among projects of this size and complexity, it was the fastest to navigate the byzantine Moscow permitting process-something that helped convince Patterson that KremlinCo. was the right locil partner choice. Given the shortage of quality office space and Russia's economic growth. Class A office market vacancy was only three percent, and rents were rising, rapidly, BIG/Lincoln's original rent assumptions from the 2004 pro forma of $500 per square meter (" m21 ) per year were now below current market rental rates of $650 per m2 just two years later. Including other revesue. the project's pro forma annual net operating income ("NOI") was $42 million (weighted average rent of $554 per ma2 ). Based on projected all-in development costs of $230million, or $3,000 per m2. this would result in a generous 18.3 percent unleveraged development yicld on cost. 4 For most of the twentieth century, new development in communist Moscow consisted of drab buildings that emphasized function over form. Modern Class A office buildings were rare but nonetheless still traded at high eap rates of over 12 percent." By building to an 18.3 percent yicld on cost in a 12 percent cap rate market, White Square was being constructed at a development premium (or 'markup') of over 50 percent. Patterson knew this was an enviable position; his pecrs in the United States and other more mature markets were building to a 15 to 25 percent markup. However, this large markup reflected the many risks inherent in a development project in an emerging market: eurrency fluctuations, political uncertainty, market instability, fluid regulatory environments, limited financing altematives, and unstable cconomic conditions. Based on Russia's improving economy and the anticipated eredit quality of the tenants that a premier project like White Square would attract, BiG.Lincoln believed it might command a market-leading cap rate upon sale of up to 10 percent, With S42 million in NOI, this would equate to a $421 million value-an eye-popping profit of $191 million. 4. The differenes betveen the yield on coat and the cap rate is the development spread. The development spread represents the profit maruin between what a ptoject cost to build and its as-built value at prevailing market rates. 5. In developed markets, cap rates are often ia the mid-single dieits for Class A office buildings, However. in smatging markts, like Russia, cap rates are higher rellecting the numerous additional ritks bofbe by investors. sens Soarer Compiled by the authary, Construction Begins B1G/Lincoln wanted to build to its typical world-class standards. Meanwhile, KremlinCo had only known poor building standards and had never seen a white-hot real estate market. Jittery that the market might evaporate overnight, KremlinCo was restless during the design process. These contrasting philosophics created nasoent tension. By early 2006. BIG/ Lincoin received construction bids from multiple general contractors. Bosphorus Construction ("Bosphorus") had the low bid and was hungry for the job. Based in Istanbul, Bosphonus had been active in Mosecw for over 15 years and was also a large owner of office buildings and shopping centers. Most of these projects were joint ventures with the City of Moscow (the "City"), offering the apparent comfort of a close relationship with the City. 5 In contrast to the secaario in many Western markets, the City was Moscow's largest landowner, a legacy of communist times when the government owned all property. Patterson believed that Bosphorus' relationship with the Ciry would come in handy, as the construction process would require many permits. However, the fact that Bosphorus was building the project while also serving as a landlord in the Moscow office rental market-and therefore a competitor-was a clear conflict of interest that gnawed at Patterson. The construction contract required Bosphorus to deliver the first of three buildings before the end of 2007. As the first building to be delivered was also the smallest building of the three (6 stories and 10,000m2 ), this timeline seened reasonable. The other two buildings (each 15 staries high, and totaling 66,000m2 ) were to be completed by September 2008. Delivery deadines were critical because BIG/Lincola intended to sign pre-leases that would include tenant-driven occupancy deadlines. A significant delay by Bosphorus would therefore require BlGILincoln to make penalty payments to the tenants. Bosphorus was only obligated to deliver the buildings in "shell and core" condition. This included all the fire and life safety systems, fully finished lobbies, lifts, and all utility connections. As was customary in Moscow, White Square tenants would be required to complete their own tenant improvements ("TIs"). It was April 2006 and, newly issued construction permit in hand. Bosphorus commenced the build of White Square as Patterson allowed himself a moment of celebration. Everything secmed to be going according to plan. Early Leasing Efforts Pay Off BIG/Lincoln had spent much of the pre-construction period in 2004 to 2005 courting intemational companies active in Moscow to sign pre-leases. Its hunch about the appeal of a 6 The Ciry of Moscow often entered into ventures with developers, making it powerful in the local converefal real eitate market. The project's 76,000m2 included 70,000m2 of offied space and 6,000m2 of retail space. "Ther contrasts with developed markets, where Tlis are typically the responsibility of the landlond. Haire Squarei A Perfect Starm in Marcow RE -140 A. Class A project in a central Moscow location was borne out as both PwC and Deloitte wanted large leases. As word of strong tenant demand spread, other premier tenants, including McKinsey \& Co., were interested in the remaining space. Smaller tenants were attractive to Parterson because non-anchor tenants paid more in rent-in some cases up to 30 percent more. In mid-2006, lease negotiations were nearly finalized with Deloitte for 30,000m2, the largest: pre-lease in Moscow history. But Deloitte balked at the idea of constructing (and paying for) Ths. The American company was conditioned to an experienced developer handling the TIs - and this proved to be both a problem and an opportunity for BIG/Lincoln. Vacancy in the Class A segment had fallen further to an unfathomable 0.5 percent and rents now exceeded $700 per m2. Earlier in the negotiation, BIG/Lincoln and Deloitte agreed to rent of $580 per m2-by 2006 , this turned out to be almost 20 pereent below the going market rate. BIG/Lincoln decided that if the team agreed to both pay for and construct Deloitte's Tls, it could push for a rent increase. It seemed a crafty way to move the rent up to market rates. BIG/Lincoln proposed financing $40 million of Deloitte's TIs ( 90 percent of the $44 miltion in estimated 7I costs) in exchange for increasing the rent to $850 per m2 and a 10 -year lease (versus the original 7 years) (see Exhibit 6). Deloitte countered by asking for signage rights, nine months of free rent, and the right to terminate for construction delays. 10 BIG/Lincoln agreed to the counter terms, although it recognized that the termination right meant exposure to significant risk if the building was not ready on schedule. To protect itself, BIG/Lincoln set the lease occupancy date for June 2009 - hine months after the scheduled construction delivery date of September 2008. By trading nine months of free rent for a higher "face" rent, Patterson created additional potential value." This also set a new market rent as a baseline for negotiating with other fenants: All in all, Patterson believed BIG/Lincoln was being well compensated for handling the Tls. Increasing the rent by $270/m2 contributed 58.1 million of additional NOI. It represented a marginal yield on $40 million in Ths of over 20 percent and a healthy development margin in excess of 50 percent. Twin Leases BIG/Lincoln's discussions with PwC to lease the other large building (32,000 m2 of space) had also reached an advanced stage. But there was a hitch. The landlord for PwC's existing office was a JV between Bosphorus and the City. The lease for that space was set to expire before White Square's scheduled completion date, necessitating a short-term extension to bridge the timing gap. With conflicting interests on all sides, BIG/Lincoln, PwC, and Bosphorus compromised. PwC's existing lease was extended to seven months after White Square's scheduled completion. PwC also wanted Deloitte's TI deal. BIG/Lincoln agreed to fund $45 million of PwC's TIs (90 percent of PwC's estimated TI cost of $50 million). The rent initially quoted to PwC (\$550 per The "Big Foar' accounting firms (Deloitte, PwC, EY, and KPMG) Were the four largest professional services networks in the world, offering audit, taxation, managenvent consulting, actuarial, and coeporate finance services. 10 Signage rights at a developenent of White Squure's proninence had real cconoenic vatue as a way to market to tenants. II When NOI increased, project value would go up by a moltiple-the reciprocal of the cap rate. m2) was even lower than the rent to which Deloitte had initially agreed ( $580 per m2). PwC's rent was raised to $850 per m2, matehing Deloitte's rent. The Fix is In... With over 80 percent of White Square pre-leased to PwC and Deloitte at rents of $850 per m2, pro forma NOI had inereased to $71 million ( 70 percent higher than the initial 2004 pro forma of $42 million). Including the $85 million in TIs for Deloitte and PwC, the all-in development costs had also increased (to $315 million) but the unleveraged development yield on cost had increased to 22.6 percent - versus the original pro forma of 18.3 pereent. With high-quality tenants and a growing number of investors searching for acquisitions in the supply-constrained Moscow market, BlG/Lincoln now believed it could achieve a cap rate closer to 9 percent at sale. This would imply a value of $790 miltion on development costs of $315 million-a profit of $475 million, nearly four times the initial pro forma profit of $121 million. The new pro forma looked great in BIG/Lincoln's financial model. But behind the numbers, BIGLLincoln had dialed up its construction risk. BIG/Lincoln had added $85 miltion in cost, nearly double the $100 million original hard cost budget, and significantly inereased construction management complexity by taking on the construction. Both PwC and Deloitte were large, international firms with dozens of partners in Moscow. Such partnerships often have heated debates about office space design, resulfing in frequent change requests and adding to the construction timeline. Source: Compracu py une aurnors. In parallel with the permitting and leasing efforts, BIG/Lincoln had been seeking construction financing. Hypoveireinsbank ("Hypobank") was a German bank that had been succesaful in Central Europe for years in the difficult emerging markets. The bank had made multiple loans to BIG/Lincoln in Central Europe and was anxious to access the Russian market through a borrower with whom they had experience in other markets. White Square checked all the boxes. By summer 2006. BIG/Lincoln and Hypobank had agreed to a $215 million loan, 70 percent of the $315 million in project costs-reflecting the value of the pre-leases (and reducing the bank's risk). As Russian author Leo Tolstoy once wrote, "It was sunoth on paper, but we forgot about the ravines," In fact, the development was nowhere near as smooth as it appenred on paper. By January 2007, only nine months after construction started, Bosphorus was already six months behind sehedule. The contractor had recently taken on several large projects without having enough labor or equignent to handle them all simultaneously. Rumors spread that Besphorus was moving labor and equipment between the job sires frequently to mask its resource limitaticns. During 2007 and 2008 , there were ominous signs of trouble thronghout the world economy, and the U.S. dollar was weakening precipitously against both the Euro and the Ruble. Currency volatility could be particularly problematic in emerging markets because many of the materials could not be soureed in the market where the project was being builf. Bosphorus was buying materials from various countries in an array of currencies. Although the contract obligated Bosphons to bedge the currency risk, it had not done so-a violation of the agreement. Patierson was reminded that delegating risk management was effective only when the counterparty was capable of managing the risk itself. Because the proverbial buck stops with the developer, mistakes by vendors and service providers often became a developer's biggest problem. BIGI Lincoln also began to sense that local materials procurement was a problem. The primary materials required for the initial 19 months of construction were concrete and steel; when Patterson requested copies of tbe procurement agreements, Bosphorus refused to provide them. How Much?!?! As Pattenson's blood pressure rose, Bosphioras requested an urgent meeting, The Bosphorus project manager had a poker player's countenance as he walked into BIG/L incoln's conference room. He explained that the monopoly concrete supplier in Moscow claimed the price had doubled. The supplier demanded that Bosphorus pay the elevated price, or no concrete. 12 As Patterson listened, he wondered to himself "how much could it possibly cost?" The answer: $40 million! His mind raced. Although the contract explicitly assigned this risk to Bosphorus, it. pled financial distress and explained that BIG/Lincoln must pay the incremental cost. Patterson also knew the unfortunate maxim when working with contractors - if job losses exceed the outstanding guarantee ( $20 million), the contractor may just "walk the site," 13 Zeig Mir das Geld! ("Show Me the Money") As if on cue, Hypobank called. Its board was increasingly wary of the bank's exposure in Russia. Many of its loans were in default in other European markets. After being bailed out by the Gernan government, the bank was facing political pressure to exit the emerging markets. Hypobank handed BIGALincoln an ulfimatum: If construction of White Square was not completed by June 2009 - as mandated in the loan agreement - the bank would accelerate the loan. Hypobank's attomeys also claimed that the June 2009 completion deadline included Tls. 12 Given the high cost of aranporting concrec, sappliens often develop strong zeegraphy-based saheres of influence, where it ir cos-probsbitive for beyen to procure coecrese trom alicrnate sources. DI In the cooarruction contract. Bosphorus guaranteed a puyment of up t0520 million to Bic/incols if perfomance tenms were not mic. If Bosphonis expested its losses te ceceed this liabilify anvount, it might dreide to wakk away and forse BtGiLincolo to sue for payment of the gaarinty, leaving Patienon with a lawsait and withosit a coniractor: Huile Spwaser A Perfer Shan in Marcow KE-fa0 2. 9 The lynchpin risk that Patterson's plan had been carefully crafted to avoid was manifesting itseif as BIGULincoln's construction delivery contingency now seemed inadequate. It was becoming increasingly clear that the glue that held the whole project together was meeting the construction deadlines in the leases and loan agreements. Now What? BIG/Lincoln formulated a plan to get the tenants moved in on time. It would require Bosphorus' cooperation in a time of rapidly deterionating goodwill between the two firms, BJG/Lincoln wanted to hire a second contractor to save time by parallel processing PwC and. Deloitte's TIs on site while Bosphorus was finishing building construction. 14 Bosphorus resisted-arguing it could finish the project on time and a separate TI contractor would just disrupt beilding construction. BIG/Lincoln worried there was a more sinister problem at hand. The overall vacancy rate in Moscow had spiked from 0.5 percent to 6 percent, and cap rates were climbing for the precious few building sales in the market. Now that the Moscow office market was teetering on the edge, Bosphorus's motivations were conflicted. PwC was still paying $500 per m2 rent under a 30,000m2 lease in a Bosphorus-owned building - $15 million annually. The market had been baoyant when Bosphorus initially signed the contract, and Bosphorus was confident it could release the space vacated by PwC. Patterson was concerned Bosphorus might not complete the buildings on time even if BIG/L,incoln agreed to the $40 million price increase. BlG/Lincoln was also working on a back-up plan to replace Bosphorus altogether. However, any new contractor would demand an increased price to reflect the current market conditions. In theory. half the priee increase could be offset by collecting the $20 million guarantee from Bosphorus for its contract default. But collecting the $20 million claim was far from assured. There was another consideration: No new contractor would provide warranties for the work that Bosphorus had already completed. ' By terminating Bosphorus, BIG/Lincoln would waive the right to make future warranty claims, leaving BIG/Lincoln without remedy for any defects arising from Bosphorus' work. The absence of warranties could significantly affect the cap rate at sale and therefore reduce the exit price. There was no clear solution. But a decision had to be made quickly, as each day ate into the construction cushion. The Duel with Deloitte Adding to BIG/Lincoln's growing list of challenges, rumors were circulating about Deloitte's business. Although Deloitte originally only needed half of the 30,000m2 space, it had preleased the entire building. Deloitte planned to sublease the extm space initially, and expand over time. But with the declining economic conditions, Deloitte's growth plans proved overly aggressive as sublease prospeets dimmed. 14 Bluilding contractors prefer to finish construction before allowing a TI contractor on site. Contractors prefer to work alone to thinimize cengestion on site and to reduce 'finger pointing' and competing lability claims. is Contractors provide performance warranties as an insurance policy against the incvitable problems that arise following consinaction completion. If a defect arises after consthiction is complete, and the contriactor is decmed to be at fault, the developer can chaim demages under the warranties set forth in the construction coatract. Typically, contraclors gaarantee mechanical, electrical; and plumbing work for three years, andetare for 10 yeirs, ete. In mid-2008, as Patterson was focused on Bosphorus' construction problems and the economic environment spiraled downward, Deloitte asked for its own mecting with BIG/Lincoln. Deloitte announced it would not honor its pre-lease obligations. A peculiarity of Russian law stated that a "lease" could be signed only ance the developer received a state-registered ownership certificate-after the baildings were completed. Posturing. Deloitte argued that the pre-lease might not he binding. Patterson's local lawyers assured him that Deloitte's threat was hollow and Russian courts would side with White Square. However, suing an anchor tenant was not an appealing option. It would take time and cost moncy. It would also lead to a loan default. Deloitte demanded that BIGILincoln reduce its Jease space by half. Atthough there was never a good time for a request like this, with ballooning vacancy rates throughout Moscow and amid a periloss problem with its contractor - this qualified as a terrible time. If BIG/Lincoln did not agree to a smaller lease, Deloitte might never pay any rent. Deloitte might also just declare lical tankruptcy. BIG/Lincoln believed this was unlikely as Deloitte's global brand would be damaged. But these were challenging times and reputable companies were taking extreme actions merely to survive. KremlinCo's White Knight Although KremlinCo was a well-capitalized metals and mining company pre-crisis, it too was saddenly in peril. In the face of falling commodity prices, the company's asset-backed lenders had declared a technical loan default, citing breaches of loan-to-value covenants. Desperate for cash, KremlinCo demanded that BIG/Lincoln agree to immediately sell the project. The joint venture agreement ("JV") between BIG/Lincoln and KremlinCo provided that neither partner could require a sale until one year after construction completion-a common JV provision. These were certainly not nomal times, and agreements were being regularly re-visited, BlGLincoln had used offshore jurisdictions and the JV was governed under English law, But the business was on Russian soil, where KremlinCo had leverage. Given the conventional wisdom regarding the dangers of doing business as an outsider in Russia, Patterson did not want to "disappoint" KremlinCo. As long days bled into long nights, Patterson would dream up the darkeit misfortunes that could befall him if he fell out of favor with his partner. In its desperation, KremlinCo had found a Kazakh investor to buy White Square. Although KremininCo had been transparent with the buyer about the raft of problems at White Square, the Kazakh investor was captivated, reasoning that it could get a trophy asset at a bargain basement price. KremlinCo assured BIG/Lincoln the Kazakhs could close the purchase before construction completion, thus providing KremlinCo the liquidity it needed and BIG Life the cash it wanted. DECISION Tru: Patterson looked up from his paper-strewn desk and to the television across his office to see the latest news banner running across the bottom of the sereen: Banks had lost more than $1 trillion since the onset of the subprime morigage crisis in 2007. Meanwhile, the White House and U.S. Congress were negotiating a complicated 5800 billion stimulus package. The bottom was falling out of the U.S. real estate market, and seasoned professionals didn't know what cap rates to assame - or even if tenants would pay the next month's rent. While Siquaret A Porect Sterm in Masow RE-140. A Any decisions Patterson made in his own three-dimensional chess game would impact all parties: in complex and unpredictable ways. Although the profit would be modest, the easy way out was: the sale to the Kazakhs. But Patterson had worked tirelessly for six years to assemble the project of a lifetime. As he studied the pro formas, the range of outcomes was wide (seeFxhibit 7). Rent and cap rate assumptions could hold, or, if things continued to deteriorate, could fall to the levels of his initial 2004 pro forma-or worse. His gut and gaile told him that if he could overcome the challenges, White Square would still make an enormous profit. If he failed, he was sure to lose the project-and the $100 million his partners had entrusted to himto the bank. Patterson had one long day and ore sleepless night until his all-hands meeting with KremlinCo, BIG Life, and Lincoln in 24 hours. His partners were expecting him to come prepared with a way forward. Regardless of his recommendation, he would have to anchor the discussion around a realistic pro forma to show how the basic economics would look should the deal succeed. Under these market conditions, that was no easy task. But he would need that analysis in hand to make a thoughtful recommendation to his partners between doubling down or cashing out. The analysis would need to be firmly grounded in the context of the deal dynamics and respective partnership interests (see Exhibit 8). The questions his partners would ask ran through his head like the ominous news banners streaming across his office television. Should he agree to Bosphorus's $40 million price increase? If so, would the conflict arising from Bosphorus' role as PwC's landlord allow it to complete construction on time? Could Deloitte's downsizing request be accommodated without undermining the income for the project? Could the construction deadline be met to avoid defaulis under the loan agreement and anchor leases? Was Hypobank's threat real-and what could Patterson do to mitigate ir? How was he to equilibrate the divergent interesis of his parthers, both in terms of their respective investment capital at risk and how much they stood to gain? Did KremlinCo, BIG Life, and Patterson / Lincoln all need to walk out of the meeting with the same path forward? And the big one: Was he kidding himself? Should he just take the money and run? The elock was ticking. It was decision time, and fast. Exhibit 1 Photographic Renderings of White Square Source: Photegraphs provided by the authors. White Siquares A Rofect Sianm in Mocour RL-f40 A. 13 Exhibit 2 White Square Development Timeline Source: Compiled thy the authors. Partnership agrecments typically stipulate that prodessional investaent managers agrec to act with fiduciary responsibility when managing third-party inveslocs: fueds. The manager is requined 60 act in the interests of the: investors. Sourcet: Compiled by the awhors. The Kiussias econouny was senisitive to oil prices, and its govemment revenues even more so. In 1997, many developing Eas Asian ecconomics experienced currency crises that destabilized much of the region. This precipitated a 50 + percent fall in gebbal oil prices, which was exacerbated by a decrease in demand. The acconpanying decline in Russia's foreign exchange rescrves led to Russia's deflutt on its domestic debe on August 17. 1998 . Many Westem investors lost money when Russta's bond markets shat down. Most notably, the fund Lang-Tern Capital Management lost 54.6 billion during the worst menths of the crisis. Source: Compiled by the authors based on data provided by Global Financial Data Source: Compiled by the authors based on data provided by Global Financial Data. Sounce: Compiled by the aushers