Question: Question: Define the translanguage corriente, Explain why? ' CHAPTER 2 Language Practices and the Translanguaging Classroom Framework . LEARNING OBJECTIVES Explain what it means for

Question: Define the translanguage corriente, Explain why?

'

'

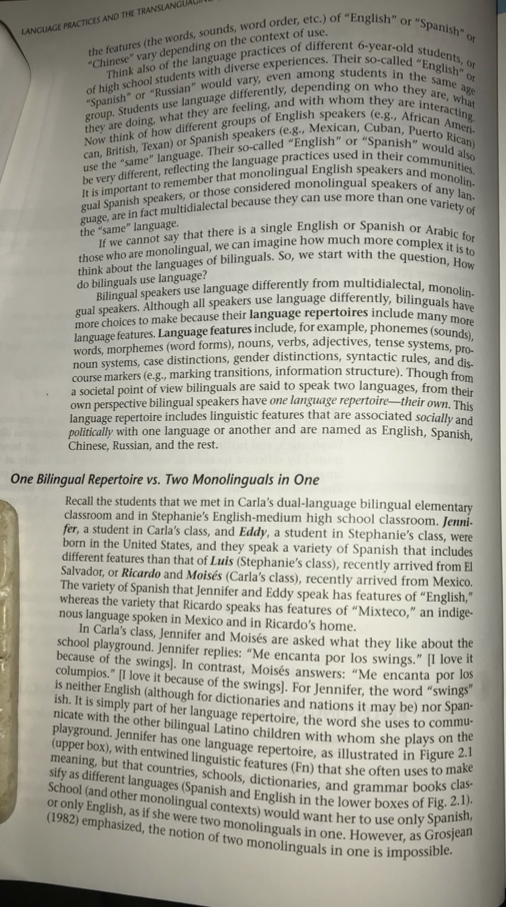

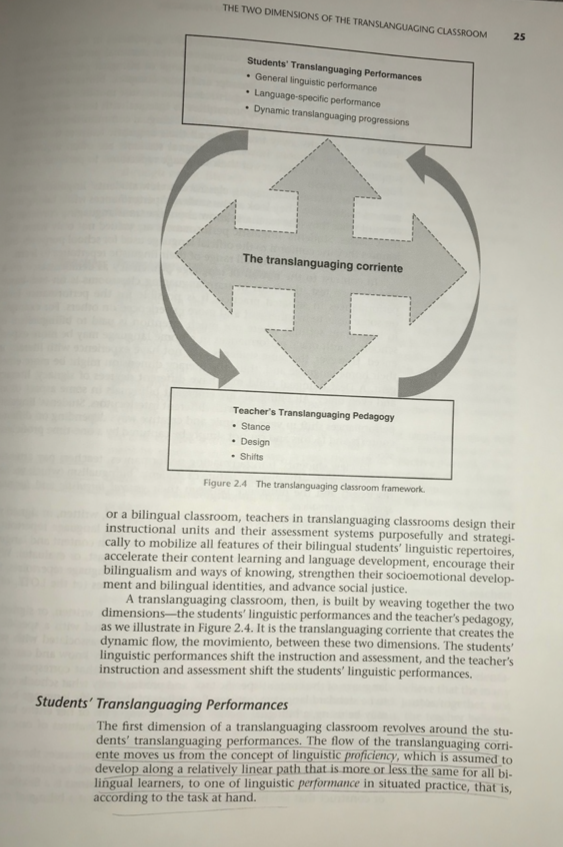

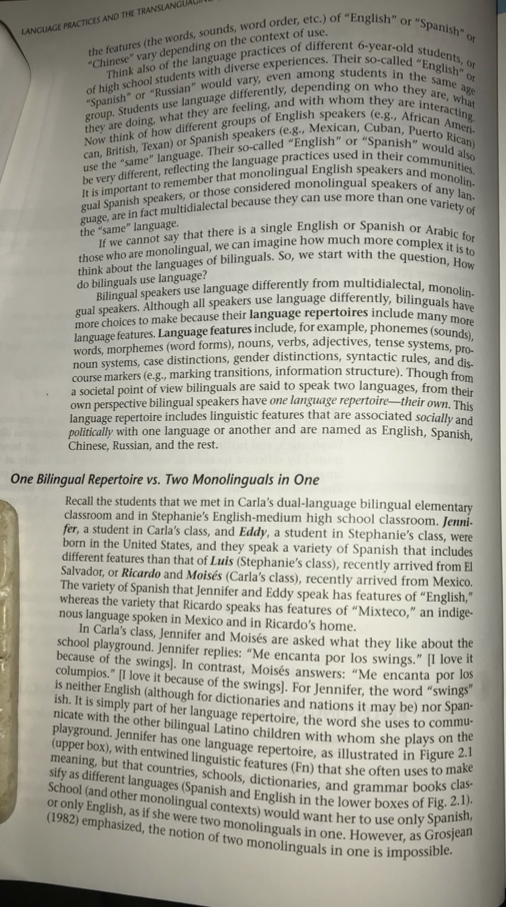

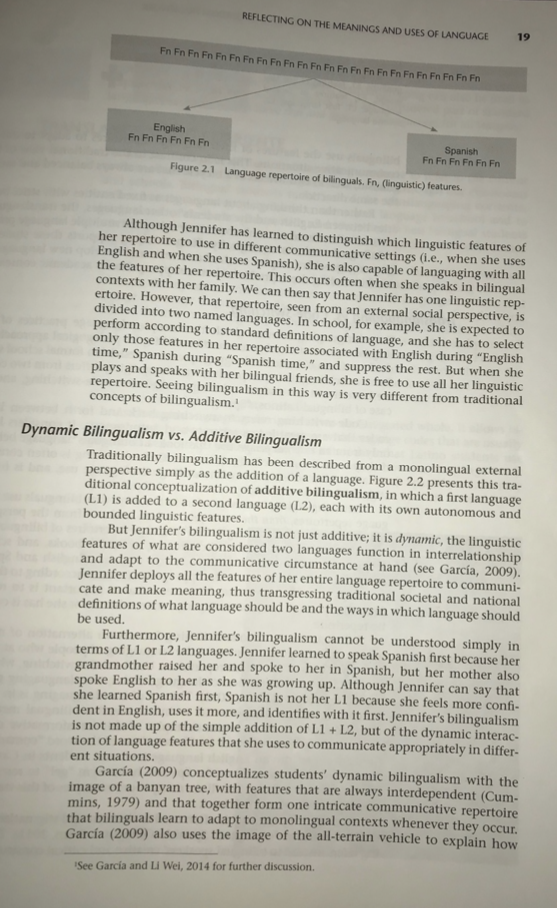

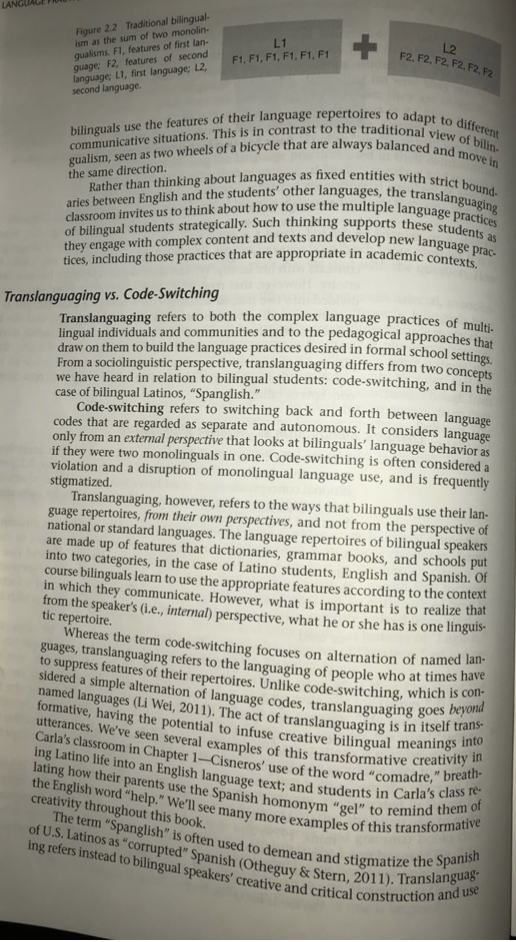

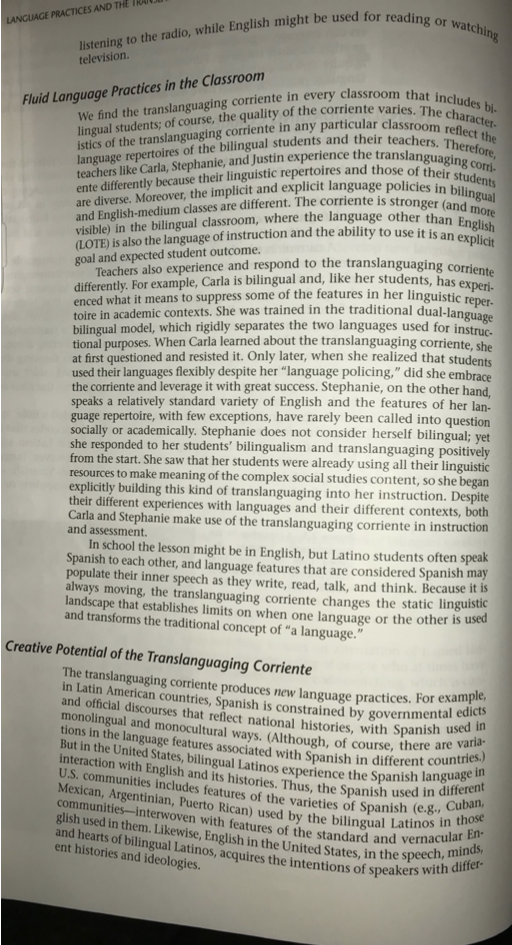

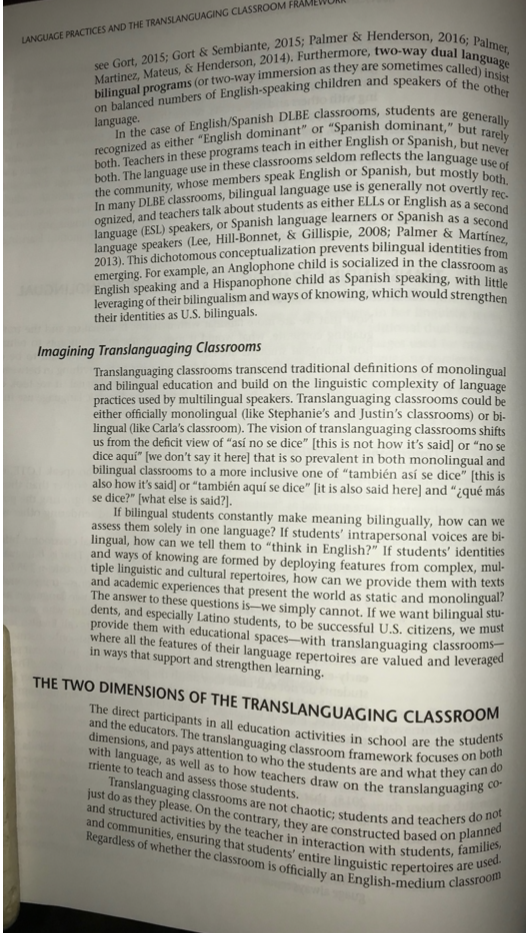

CHAPTER 2 Language Practices and the Translanguaging Classroom Framework . LEARNING OBJECTIVES Explain what it means for a bilingual student to draw on the full features of his or her linguistic repertoire . Compare and contrast the notions of dynamic bilingualism and additive bilingualism Define the translanguaging corriente Use the translanguaging classroom framework to explain how the translanguaging corriente sets learning and teaching in motion Begin to identify evidence of the translanguaging corriente in your focal classroom . This his chapter introduces the translanguaging classroom framework, which educators can use to understand translanguaging classrooms like Carla's, Stephanie's, and Justin's. First, however, we must think about how language is used by different speakers in context. When we look closely at the actual language practices of bilinguals, we see variation, dynamism, and complexity. The flow of students' bilingual practices, what we call the translanguaging corriente, is at work in all aspects of classroom life. When bilingual students engage with texts, they do so while drawing on all their linguistic resources, even if those texts are rendered only in English or only in Spanish or another language. When bilingual students write or create something new, they may filter certain features of their linguistic repertoires to create the product, but the process will always be bilingual. When we view students' bilingualism in this wayas a fluid, ever present current that they tap into to make meaning-we see bilingual students differ- ently. This shift in perspective opens new possibilities for teaching and assessing bilingual students. The translanguaging classroom framework that we propose helps teachers imagine a translanguaging pedagogy that leverages students' dynamic bilingualism for learning. REFLECTING ON THE MEANINGS AND USES OF LANGUAGE As school practitioners we often think of language solely as the standardized variety that is present in textbooks or used in assessments. We think we teach in "English," or "Spanish" or "Chinese" or "Korean" or "Russian." But the re- ality of language is a lot more complex than names of languages indicate. Think, for example, of how we use language when we are speaking, read- ing, talking to a family member, disciplining a child, teaching a class, or work- ing with an individual student. The ways we use language are different, and 17 LANGUAGE PRACTICES AND THE TRANSLANGE O "Chinese" vary depending on the context of use. same age the features (the words, sounds, word order, etc.) of "English" or "Spanish of high school students with diverse experiences. Their so-called "English" or Think also of the language practices of different 6-year-old students, of group. Students use language differently, depending on who they are, what "Spanish" or "Russian" would vary, even among students in the Now think of how different groups of English speakers (e.g., African Ameri can, British, Texan) or Spanish speakers (e.8, Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican) use the same language. Their so-called "English" or "Spanish" would also they are doing, what they are feeling, and with whom they are interacting It is important to remember that monolingual English speakers and monolin- be very different, reflecting the language practices used in their communities gual Spanish speakers, or those considered monolingual speakers of any lan guage, are in fact multidialectal because they can use more than one variety of the same language those who are monolingual, we can imagine how much more complex it is to If we cannot say that there is a single English or think about the languages of bilinguals. So, we start with the question, How do bilinguals use language? Bilingual speakers use language differently from multidialectal, monolin- more choices to make because their language repertoires include many more gual speakers. Although all speakers use language differently, bilinguals have language features. Language features include, for example, phonemes (sounds), Spanish or Arabic for words, morphemes (word forms), nouns, werbs, adjectives, tense systems, pro noun systems, case distinctions, gender distinctions, syntactic rules, and dis- course markers (2.g., marking transitions, information structure). Though from a societal point of view bilinguals are said to speak two languages, from their own perspective bilingual speakers have one language repertoiretheir own. This language repertoire includes linguistic features that are associated socially and politically with one language or another and are named as English, Spanish, Chinese, Russian, and the rest. One Bilingual Repertoire vs. Two Monolinguals in One Recall the students that we met in Carla's dual-language bilingual elementary classroom and in Stephanie's English-medium high school classroom. Jenni- fer, a student in Carla's class, and Eddy, a student in Stephanie's class, were born in the United States, and they speak a variety of Spanish that includes different features than that of Luis (Stephanie's class), recently arrived from El Salvador, or Ricardo and Moiss (Carla's class), recently arrived from Mexico. The variety of Spanish that Jennifer and Eddy speak has features of "English," whereas the variety that Ricardo speaks has features of "Mixteco," an indige- nous language spoken in Mexico and in Ricardo's home. In Carla's class, Jennifer and Moiss are asked what they like about the school playground. Jennifer replies: "Me encanta por los swings." [I love it because of the swings). In contrast, Moiss answers: Me encanta por los columpios." [I love it because of the swings). For Jennifer, the word "swings" is neither English (although for dictionaries and nations it may be) nor Span. nicate with the other bilingual Latino children with whom she plays ish. It is simply part of her language repertoire, the word she uses to commu- playground. Jennifer has one language repertoire, as illustrated in Figure 2 (upper box), with entwined linguistic features (Fn) that she often uses to make meaning, but that countries, schools, dictionaries, and grammar books clas- School (and other monolingual contexts) would want her to use only Spanish, sify as different languages (Spanish and English in the lower boxes of Fig. 2.1). or only English, as if she were two monolinguals in one. However, as Grosjean (1982) emphasized, the notion of two monolinguals in one is impossible. on the REFLECTING ON THE MEANINGS AND USES OF LANGUAGE 19 Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn En Fn Fn Fn En Fn En Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn En Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn English Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn Spanish Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn Fn Figure 2.1 Language repertoire of bilinguals. Fn, (linguistic) features. Although Jennifer has learned to distinguish which linguistic features of her repertoire to use in different communicative settings (i.e., when she uses English and when she uses Spanish), she is also capable of languaging with all the features of her repertoire. This occurs often when she speaks in bilingual contexts with her family. We can then say that Jennifer has one linguistic rep- ertoire. However, that repertoire, seen from an external social perspective, is divided into two named languages. In school, for example, she is expected to perform according to standard definitions of language, and she has to select only those features in her repertoire associated with English during "English time," Spanish during "Spanish time," and suppress the rest. But when she plays and speaks with her bilingual friends, she is free to use all her linguistic repertoire. Seeing bilingualism in this way is very different from traditional concepts of bilingualism. Dynamic Bilingualism vs. Additive Bilingualism Traditionally bilingualism has been described from a monolingual external perspective simply as the addition of a language. Figure 2.2 presents this tra- ditional conceptualization of additive bilingualism, in which a first language (L1) is added to a second language (L2), each with its own autonomous and bounded linguistic features. But Jennifer's bilingualism is not just additive; it is dynamic, the linguistic features of what are considered two languages function in interrelationship and adapt to the communicative circumstance at hand (see Garca, 2009). Jennifer deploys all the features of her entire language repertoire to communi- cate and make meaning, thus transgressing traditional societal and national definitions of what language should be and the ways in which language should be used. Furthermore, Jennifer's bilingualism cannot be understood simply in terms of L1 or L2 languages. Jennifer learned to speak Spanish first because her grandmother raised her and spoke to her in Spanish, but her mother also spoke English to her as she was growing up. Although Jennifer can say that she learned Spanish first, Spanish is not her L1 because she feels more confi- dent in English, uses it more, and identifies with it first. Jennifer's bilingualism is not made up of the simple addition of L1 + L2, but of the dynamic interac- tion of language features that she uses to communicate appropriately in differ- ent situations Garca (2009) conceptualizes students' dynamic bilingualism with the image of a banyan tree, with features that are always interdependent (Cum- mins, 1979) and that together form one intricate communicative repertoire that bilinguals learn to adapt to monolingual contexts whenever they occur. Garca (2009) also uses the image of the all-terrain vehicle to explain how See Garcia and Ll Wel, 2014 for further discussion Figure 2.2 Traditional bilingual ism as the sum of two monolin- gualisms. F1, features of first lan guage: F2, features of second language; LI, first language; L2, second language. L1 F1, F1, F1, F1, F1, F1 + L2 F2, F2, F2, F2, F2, F2 the same direction. communicative situations. This is in contrast to the traditional view of bilin. bilinguals use the features of their language repertoires to adapt to different gualism, seen as two wheels of a bicycle that are always balanced and move in Rather than thinking about languages as fixed entities with strict bound. aries between English and the students' other languages, the translanguaging of bilingual students strategically. Such thinking supports these students as classroom invites us to think about how to use the multiple language practices they engage with complex content and texts and develop new language prac. tices, including those practices that are appropriate in academic contexts. Translanguaging vs. Code-Switching Translanguaging refers to both the complex language practices of multi. lingual individuals and communities and to the pedagogical approaches that draw on them to build the language practices desired in formal school settings. From a sociolinguistic perspective, translanguaging differs from two concepts we have heard in relation to bilingual students: code-switching, and in the case of bilingual Latinos, "Spanglish." Code-switching refers to switching back and forth between language codes that are regarded as separate and autonomous. It considers language only from an external perspective that looks at bilinguals' language behavior as if they were two monolinguals in one. Code-switching is often considered a violation and a disruption of monolingual language use, and is frequently stigmatized. Translanguaging, however, refers to the ways that bilinguals use their lan- guage repertoires, from their own perspectives, and not from the perspective of national or standard languages. The language repertoires of bilingual speakers are made up of features that dictionaries, grammar books, and schools put into two categories, in the case of Latino students, English and Spanish. Of course bilinguals learn to use the appropriate features according to the context in which they communicate. However, what is important is to realize that from the speaker's (i.e., internal) perspective, what he or she has is one linguis- tic repertoire. Whereas the term code-switching focuses on alternation of named lan- guages, translanguaging refers to the languaging of people who at times have to suppress features of their repertoires. Unlike code-switching, which is cona sidered a simple alternation of language codes, translanguaging goes beyond named languages (Li Wei, 2011). The act of translanguaging is in itself trans- formative, having the potential to infuse creative bilingual meanings into utterances. We've seen several examples of this transformative creativity in Carla's classroom in Chapter 1-Cisneros' use of the word "comadre," breath- ing Latino life into an English language text; and students in Carla's class re- lating how their parents use the Spanish homonym "gel" to remind them of the English word "help." We'll see many more examples of this transformative The term "Spanglish" is often used to demean and stigmatize the Spanish of U.S. Latinos as "corrupted" Spanish (Otheguy & Stern, 2011). Translanguag. ing refers instead to bilingual speakers' creative and critical construction and use creativity throughout this book. TRANSLANGUAGING CORRIENTE 21 of interrelated language features that can be used for learning, and that teach- ers can leverage, regardless of the quality of students' performances in one or another national language. Furthermore, translanguaging can also be used to acquire and to learn how to use features that are considered part of standard language practices, which have real and material consequences for all learners. TRANSLANGUAGING CORRIENTE We use the metaphor of the translanguaging corriente to refer to the current or flow of students' dynamic bilingualism that runs through our classrooms and schools. Bilingual students make use of the translanguaging corriente, either overtly or covertly, to learn content and language in school and to make sense of their complex worlds and identities. When bilingual students work together to carry out an academic task, they negotiate and make mean- ing by pooling all of their linguistic resources. A current in a body of water is not static; it runs a changeable course de pending on features of the landscape. Likewise, the translanguaging corriente refers to the dynamic and continuous movement of language features that change the static linguistic landscape of the classroom that is described and defined from a monolingual perspective. Figure 2.3 represents the translan guaging corriente flowing and changing terrain that is traditionally consid- ered "English" or "home language" territory and connecting them. From the surface, we see two separate riverbanks, with each side showing distinct fea- tures. Depending on the current, however, the riverbanks shift and their fea- tures change. And at the river bottom, the terrain is one; the river and its two banks are in fact one integrated whole. As the translanguaging corriente forms an integrated whole, it allows bi- lingual students to combine social spaces with language codes that are usually practiced separately. For example, it is often said that Latino students use Spanish at home and English in school. In reality, however, language use is more fluid. In Latino homes, some families may speak Spanish; others may speak English; and most speak both. Spanish might be spoken or used while Figure 2.3 A metaphor for the translanguaging corriente. (Re. trieved from https://www.flickr .com/photos/79666107@N00/ 4120780342/) LANGUAGE PRACTICES AND THE listening to the radio, while English might be used for reading or watching television Fluid Language Practices in the Classroom We find the translanguaging corriente in every classroom that includes bi. istics of the translanguaging corriente in any particular classroom reflect the lingual students; of course, the quality of the corriente varies. The character language repertoires of the bilingual students and their teachers. Therefore, teachers like Carla, Stephanie, and Justin experience the translanguaging corri ente differently because their linguistic repertoires and those of their students are diverse. Moreover, the implicit and explicit language policies in bilingual and English-medium classes are different. The corriente is stronger and more visible) in the bilingual classroom, where the language other than English (LOTE) is also the language of instruction and the ability to use it is an explicit goal and expected student outcome. Teachers also experience and respond to the translanguaging corriente differently. For example, Carla is bilingual and, like her students, has experi- . toire in academic contexts. She was trained in the traditional dual-language bilingual model, which rigidly separates the two languages used for instruc tional purposes. When Carla learned about the translanguaging corriente, she at first questioned and resisted it. Only later, when she realized that students used their languages flexibly despite her "language policing," did she embrace the corriente and leverage it with great success. Stephanie, on the other hand, speaks a relatively standard variety of English and the features of her lan guage repertoire, with few exceptions, have rarely been called into question socially or academically. Stephanie does not consider herself bilingual; yet she responded to her students' bilingualism and translanguaging positively from the start. She saw that her students were already using all their linguistic resources to make meaning of the complex social studies content, so she began explicitly building this kind of translanguaging into her instruction. Despite their different experiences with languages and their different contexts, both Carla and Stephanie make use of the translanguaging corriente in instruction and assessment. In school the lesson might be in English, but Latino students often speak Spanish to each other, and language features that are considered Spanish may populate their inner speech as they write, read, talk, and think. Because it is always moving, the translanguaging corriente changes the static linguistic landscape that establishes limits on when one language or the other is used and transforms the traditional concept of "a language." Creative Potential of the Translanguaging Corriente in Latin American countries, Spanish is constrained by governmental edicts The translanguaging corriente produces new language practices. For example, and official discourses that reflect national histories, with Spanish used in monolingual and monocultural ways. (Although, of course, there are varia- tions in the language features associated with Spanish in different countries.) But in the United States, bilingual Latinos experience the Spanish language in Interaction with English and its histories. Thus, the Spanish used in different Mexican, Argentinian, Puerto Rican) used by the bilingual Latinos in those U.S. communities includes features of the varieties of Spanish (e.g., Cuban, glish used in them. Likewise, English in the United States, in the speech, minds, communities-interwoven with features of the standard and vernacular En- and hearts of bilingual Latinos, acquires the intentions of speakers with differ- ent histories and ideologies. INS OF MONOLINGUAL AND BILINGUAL CLASSROOMS 23 Thus, U.S. Latinos, as well as other bilinguals, experience "language" and histories constructed through one or another named "language" as an inte grated system of linguistic and cultural practices. The translanguaging corri- ente generates the creative energy and produces the speaker's way of interact- ing with others and other texts, rather than responding to restrictions imposed by the officially accepted way of using language. It involves, as Li Wei (2011) has said, going both between different linguistic structures, systems, and mo. dalities, and going beyond them. For Li Wei, translanguaging "creates a social space for the multilingual user by bringing together different dimensions of their personal history, experience, and environment; their attitude, belief, and ideology; (and) their cognitive and physical capacity into one coordinated and meaningful performance" (p. 1223). In short, the translanguaging corriente is generated by the students' bilingualism, and it sets in motion learning and teaching in the translanguaging classroom. TRANSCENDING TRADITIONAL NOTIONS OF MONOLINGUAL AND BILINGUAL CLASSROOMS Now that we are more familiar with dynamic bilingualism and the translan- guaging corriente, what would it mean to use these concepts to reimagine how bilingual students are educated? U.S. classrooms are said to be either monolingual or bilingual; there does not seem to be anything in between. But classrooms today are never just monolingual or bilingual. If we look closer, there is much more diversity, and much more dynamic language use in class- rooms, than what we hear and see at the surface level. Limitations of Traditional Models In any "monolingual" classroom we find children who speak LOTE, even if they also speak English. By ignoring linguistic practices other than those that are regarded as "legitmate school English," schools are ignoring the potential to build on a child's entire linguistic repertoire and rendering other ways of speaking invisible. Furthermore, despite the existence of many bilingual classrooms, bilingual education often suffers from a monoglossic ideology. That is, bilingualism is often understood as simply "double monolingualism" (Grosjean 1982; Heller, 1999). Both major types of bilingual education classrooms-transitional bilin- gual and dual-language bilingual-conceptualize the two languages as sepa- rate. Transitional bilingual classrooms transition children who are acquiring English (those we call emergent bilinguals and others call English language learners (ELLS) or limited English proficient) to English-only instruction. In early-exit programs the transition is as soon as possible. In late-exit programs, students do not exit until they finish the program of instruction. The propor- NOOtion of English used for instruction increases as the use of the other language decreases. English language development, then, never benefits from its inter- relationship with the existing language features of the student's language rep- ertoire. And Spanish development is not supported over time. Most dual-language bilingual education (DLBE) classrooms also suffer from the same monoglossic ideology (Garca, 2009; Martnez, Hikida, & Durn, 2015), that is, the idea that the two languages are to be used only in monolin- gual ways. Echoing this idea, Fitts (2006) demonstrates how language separa- tion in DLBE programs is a mechanism that "authorizes the use of standard forms of English and Spanish in separate spaces, and illegitimizes the use of vernaculars" (p. 339). The prototypical dual language model (which we refer to as dual-language bilingual education) requires that English and the partner lan- guage always remain separate (for critiques of the language separation approach, LANGUAGE PRACTICES AND THE TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOM FRA see Gort, 2015; Gort & Sembiante, 2015; Palmer & Henderson, 2016; Palmer, Martinez, Mateus, & Henderson, 2014). Furthermore, two-way dual language bilingual programs (or two-way immersion as they are sometimes called) insist on balanced numbers of English-speaking children and speakers of the other language recognized as either "English dominant" or "Spanish dominant," but rarely In the case of English/Spanish DLBE classrooms, students are generally both. Teachers in these programs teach in either English or Spanish, but never both. The language use in these classrooms seldom reflects the language use of the community, whose members speak English or Spanish, but mostly both. In many DLBE classrooms, bilingual language use is generally not overtly rec- ognized, and teachers talk about students as either ELLs or English as a second language (ESL) speakers, or Spanish language learners or Spanish as a second language speakers (Lee, Hill-Bonnet, & Gillispie, 2008; Palmer & Martnez, 2013). This dichotomous conceptualization prevents bilingual identities from emerging. For example, an Anglophone child is socialized in the classroom a English speaking and a Hispanophone child as Spanish speaking, with little leveraging of their bilingualism and ways of knowing, which would strengthen their identities as U.S. bilinguals. Imagining Translanguaging Classrooms Translanguaging classrooms transcend traditional definitions of monolingual and bilingual education and build on the linguistic complexity of language practices used by multilingual speakers. Translanguaging classrooms could be either officially monolingual (like Stephanie's and Justin's classrooms) or bi- lingual (like Carla's classroom). The vision of translanguaging classrooms shifts us from the deficit view of "as no se dice" (this is not how it's said] or "no se dice aqu" (we don't say it here that is so prevalent in both monolingual and bilingual classrooms to a more inclusive one of "tambin as se dice" (this is also how it's said] or "tambin aqu se dice" [it is also said here) and "qu ms se dice?" (what else is said?). If bilingual students constantly make meaning bilingually, how can we assess them solely in one language? If students' intrapersonal voices are bi- lingual, how can we tell them to think in English?" If students' identities and ways of knowing are formed by deploying features from complex, mul- tiple linguistic and cultural repertoires, how can we provide them with texts and academic experiences that present the world as static and monolingual? The answer to these questions is-we simply cannot. If we want bilingual stu dents, and especially Latino students, to be successful U.S. citizens, we must provide them with educational spaceswith translanguaging classrooms. where all the features of their language repertoires are valued and leveraged in ways that support and strengthen learning. THE TWO DIMENSIONS OF THE TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOM The direct participants in all education activities in school are the students and the educators. The translanguaging classroom framework focuses on both with language, as well as to how teachers draw on the translanguaging co- dimensions, and pays attention to who the students are and what they can do just do as they please. On the contrary, they are constructed based on Translanguaging classrooms are not chaotic; students and teachers do not and structured activities by the teacher in interaction with students, families, and communities, ensuring that students' entire linguistic repertoires are used. Regardless of whether the classroom is officially an English-medium classroom rriente to teach and assess those students. planned THE TWO DIMENSIONS OF THE TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOM 25 Students' Translanguaging Performances General linguistic performance Language-specific performance Dynamic translanguaging progressions The translanguaging corriente Teacher's Translanguaging Pedagogy Stance Design Shirts Figure 2.4 The translanguaging classroom framework. or a bilingual classroom, teachers in translanguaging classrooms design their instructional units and their assessment systems purposefully and strategi- cally to mobilize all features of their bilingual students' linguistic repertoires, accelerate their content learning and language development, encourage their bilingualism and ways of knowing, strengthen their socioemotional develop ment and bilingual identities, and advance social justice. A translanguaging classroom, then, is built by weaving together the two dimensions--the students' linguistic performances and the teacher's pedagogy, as we illustrate in Figure 2.4. It is the translanguaging corriente that creates the dynamic flow, the movimiento, between these two dimensions. The students' linguistic performances shift the instruction and assessment, and the teacher's instruction and assessment shift the students' linguistic performances. Students' Translanguaging Performances The first dimension of a translanguaging classroom revolves around the stu- dents' translanguaging performances. The flow of the translanguaging corri- ente moves us from the concept of linguistic proficiency, which is assumed to develop along a relatively linear path that is more or less the same for all bi- lingual learners, to one of linguistic performance in situated practice, that is, according to the task at hand. LANGUAGE PRACTICES AND THE English or Spanish lingualism in the United States, considered even minimal proficiency in two Both Haugen (1953) and Weinreich (1979), pioneers in the study of the today's students, however, is broader and more complex. Bilinguals today languages as a sign of bilingualism. The range of bilingual performances of quire and use many different linguistic features because mobility and techno whose repertoires differ from their own. In bilingual communities and homes ogy have given them more opportunities to interact with texts and speakers speakers do not shy away from using all their linguistic features to commu- nicate. In most schools, however, bilingual students are often required to suppress half of the features of their language repertoires to perform only in Teachers in translanguaging classrooms view students' linguistic perfor mances holistically. They look at the students' performances while taking into their classes. Students' linguistic performances are valued not only when the account what they (the teachers) know about the translanguaging corriente in features they use conform to the official language used for school purposes, but In contrast to the notion of language proficiency as demonstrated on a standardized test, the focus in translanguaging classrooms is on task-based performances in situated practice. It is possible for the performance level on some tasks to be emergent and more experienced on others. For example, in immigrant settings where not much attention is paid to bilingualism in schools, youth oracy performances in a home language may be more experi- enced. However, the same students may not have experience with literacy in their home language and, thus, the literacy dimension might be more emer- gent. A Deaf bilingual child may have different degrees of signacy, literacy, and even oracy. All bilinguals are emergent bilinguals in some aspect or an- other, in certain situations and with different interlocutors. Students' linguistic performances shift in very dynamic and creative ways depending on different contexts and factors and cannot simply be captured by a one-time proficiency score. To view students' translanguaging performances, teachers pay attention to two elements-the dynamic nature of students' bilingualism (which we have discussed) and the difference between their general linguistic and language- specific performances. General linguistic performance refers to an oral, written, or signed per- formance that draws on a bilingual speaker's entire language repertoire to demonstrate what that speaker knows and can do with content and language (e.g., to explain, persuade, argue, compare and contrast, or evaluate). When bilingual speakers draw on the full features of their language repertoires, they are not required to suppress specific linguistic features of the LOTE, of the formance that only draws on those features associated with a specific lani Language-specific performance refers to an oral, written, or signed per guage; here we focus on standard language features associated with school contexts. Bilingual speakers, to demonstrate what they know and can do, de ploy only the features in their language repertoires that correspond language of the content-specific task, and produce only what schools consider may be using, a bilingual speaker always leverages his or her entire language to be standard language features. Regardless of the specific language he or she vernacular variety of a language, etc.). to the repertoire to make meaning, even when only using features of one language. we call the dynamic translanguaging progressions, which will be further discussed Teachers can view students' translanguaging performances through what in Chapter 3. The dynamic translanguaging progressions is a flexible model or construct that teachers can use to look holistically at a bilingual student's specific THE TWO DIMENSIONS OF THE TRANSLANGUAGING CLASSROOM 27 general linguistic and language-specific performances on different tasks at dif- ferent times from different perspectives. These progressions are dynamic be- cause they provide evidence of how a bilingual student's bilingualism ebbs and flows with experiences and opportunities. The dynamic translanguaging progressions model stands in contrast to traditional language models that see language development as a relatively linear, unidirectional, stage-like process, As we will see in Chapter 3, the dynamism of students' translanguaging performances makes it clear that bilingualism is not static; it is not attainable; it is not something that one purely "has." On the contrary, one needs to "do" bilingualism-work with it, use it, perform it in different ways, whether through oracy, literacy, or signacy (for Deaf populations)-or any combina- tion thereof. Bilingual students also need to understand the potential of their linguistic performances when they are allowed to use all the features of their language repertoires, that is, when schools also legitimize their translanguag. ing performances Teachers' Translanguaging Pedagogy The second dimension of the translanguaging classroom framework focuses attention on the teacher's instruction and assessment, which adapt to, and leverage, the students' translanguaging performances. The translanguaging pedagogy we propose, and that will be developed in Part II, includes the teach- er's general stance toward the students' dynamic bilingualism, the intentional ways that teachers design curricular units of instruction and assessments to build on what students can do with the full features of their language reper- toires, and the moment-to-moment shifts that teachers make in response to their observation of student participation in language-mediated classroom activities. Although some teachers understand the power of translanguaging and are able to give students this flexibility so that they can translanguage mo- ment-by-moment in their classes, it takes thoughtful, effective planning. That is, it is not enough to go with flow of the translanguaging corriente. A teacher needs to have a translanguaging stance, build a translanguaging design, and make translanguaging shifts--the three strands of the translanguaging pedagogy We explain how to develop these strands in both instruction and assess- ment in later chapters. Here we simply introduce them. Stance A stance refers to the philosophical, ideological, or belief system that teachers draw from to develop their pedagogical framework. Teachers cannot leverage the translanguaging corriente without the firm belief that by bringing forth bilingual students' entire language repertoires they can transcend the lan- guage practices that schools traditionally have valued. Clearly, teachers with a translanguaging stance have a firm belief that their students' language prac- tices are both a resource and a right (Ruiz, 1984). But beyond these orienta tions to language, teachers with a translanguaging stance believe that the many different language practices of bilingual students work juntos/together, not separately as if they belonged to different realms. Thus, the teacher believes that the classroom space must be used creatively to promote language collab- oration. A translanguaging stance always sees the bilingual child's complex language repertoire as a resource, never as a deficit. We see the influence of this translanguaging stance in educators' actions. Our planned actions as teachers in translanguaging classrooms are what we term the translanguaging design. GE PRACTICES AND THE Design struction and assessments that build connections between, as Flores and Teachers in translanguaging classrooms must design units, lessons, and in. Schissel (2014) say, "/community] language practices and the language prac. tional and assessment design does not simply direct the translanguaging co. tices desired in formal school settings" (p. 462). The translanguaging instruc- rriente toward the school and away from the home or simply construct a bridge across the two banks (home and school) of the river. Instead, teachers pur. posefully design instruction and assessment opportunities that integrate home and school language and cultural practices. Learning is created by the translan. guaging corriente that teachers and students jointly navigate to reduce the distance between home and school practices. This translanguaging design is what prevents learners from being swept away by different currents--those created by school language practices that are beyond their reach or those of home language practices that, without blending with those of the school, do not lead to academic success. But the translanguaging design is not a simple scaffold for the kinds of languaging and understanding that the school deems valuable. Instead, students' bilin gual practices and ways of knowing are seen as both informing and informed by classroom instruction. The design is the pedagogical core of the translanguaging classroom. But to open ourselves and our students to constructing this flexible design to- gether, we need to make room for translanguaging shifts. Shifts Because the translanguaging corriente is always present in classrooms, it is not enough to simply have a stance that recognizes translanguaging performances and a design that directs it. At times it is also important to follow el movi. miento de la corriente. The translanguaging shifts refer to the many moment by-moment decisions that teachers make in the classroom. They reflect the teacher's flexibility and willingness to change the course of the lesson, as well as the language use planned in instruction and assessment, to release and sup- port students' voices. The translanguaging shifts are related to the translan guaging stance, for it takes a teacher willing to keep meaning-making and learning at the center of all instruction and assessment to go with the flow of the corriente. Teachers can use the translanguaging pedagogy to leverage the translan guaging corriente that runs through their classes. This translanguaging pedas gogy encompasses both instruction and assessment, and can be used to mobi- The strands of the translanguaging pedagogy are interrelated and form a sturdy but flexible rope that strengthens the learning and teaching of both through the daily life of the classroom-planning lessons, facilitating con These interrelated strands enable the translanguaging corriente to flow versations about content, strengthening of students' general linguistic and language and content, as shown in Figure 2.5. Figure 2.5 The translanguaging pedagogy strands. Stance Design Shits CONCLUSION 29 language-specific performances, and assessing student growth along the dy namic translanguaging progressions. These strands also weave together the four translanguaging purposes: 1. To support student engagement with complex content and texts 2. To provide opportunities for students to develop linguistic practices for academic contexts 3. To make space for students' bilingualism and ways of knowing, 4. To support students' socioemotional development and bilingual identities Together the strands of this pedagogy secure not only these educational poses, but also connect the educational project to a higher goal-constructing a more just world, especially for minority students. pur- CONCLUSION This chapter has encouraged our reflections on language use through the mov- imiento of the translanguaging corriente, and especially the language use of bilingual students. In so doing, we questioned notions of additive bilingual- ism and took up the concept of dynamic bilingualism. We then explored the concepts of translanguaging and the translanguaging corriente. We introduced the two dimensions of the translanguaging classroom framework-the stu- dents' translanguaging performances and the teacher's translanguaging peda- gogy. We also identified the three strands that make up the translanguaging pedagogy for instruction and assessment-the stance, design, and shifts. QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 1. Have you ever experienced or felt the translanguaging corriente? Where and why? How did it make you feel? 2. How does the concept of bilingual students' translanguaging performances differ from traditional concepts of language proficiency? 3. What are the challenges that translanguaging poses for you? Identify and talk through with other educators the challenges posed by each of the three strands--the stance, design, and shifts. TAKING ACTION 1. Visit the bilingual community of your choice. Listen to the ways that language is used in the street, in the stores, and in the restaurants. What do you hear? Look for signs written by store owners and others. What can you conclude about the ways that bi- lingualism is used in this community? How does it adjust (or not) to the concept of dynamic bilingualism discussed here? 2. What evidence of the translanguaging corriente can you see and hear in your focal classroom? Take notes on the ways that your bilingual students draw on all of the features of their linguistic repertoire orally and in writing in different communicative activities at school

'

'