Question: What does the Tipping Point chapter teach us about bringing about change in fearful, hostile, and politicized environments? What have you learned about how to

What does the Tipping Point chapter teach us about bringing about change in fearful, hostile, and politicized environments? What have you learned about how to overcome these negative factors?

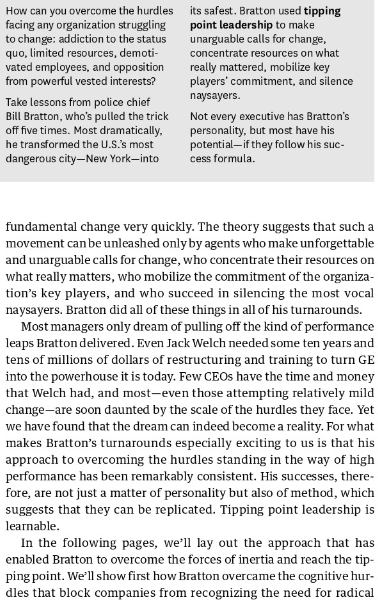

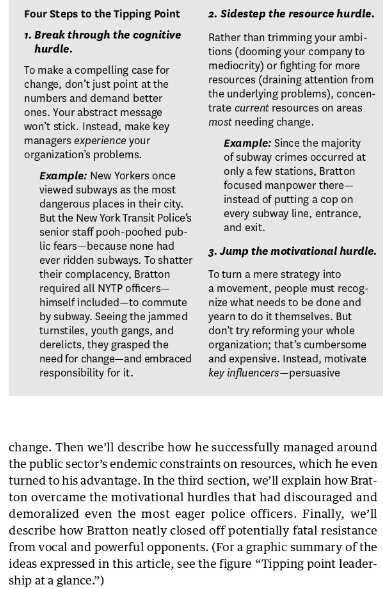

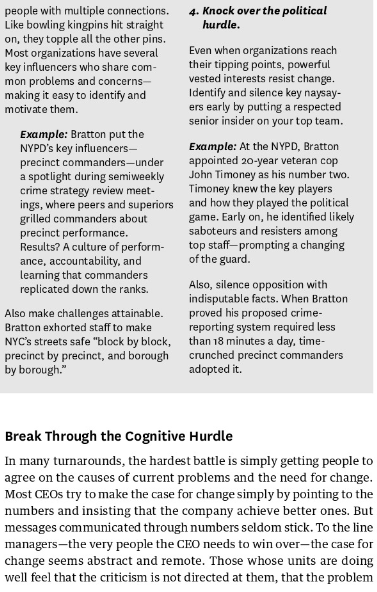

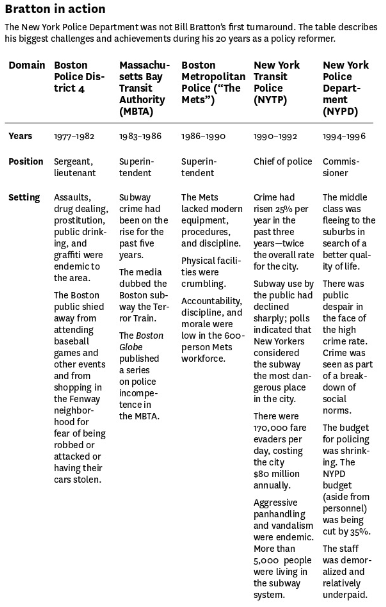

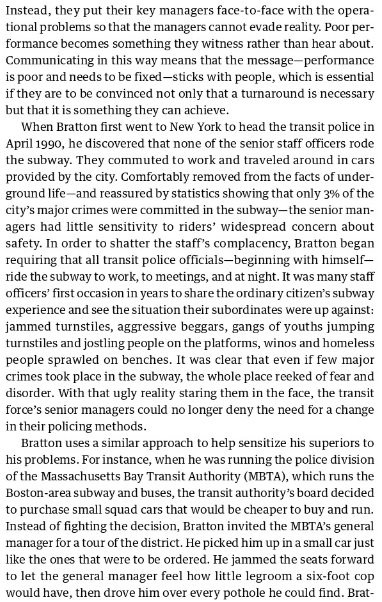

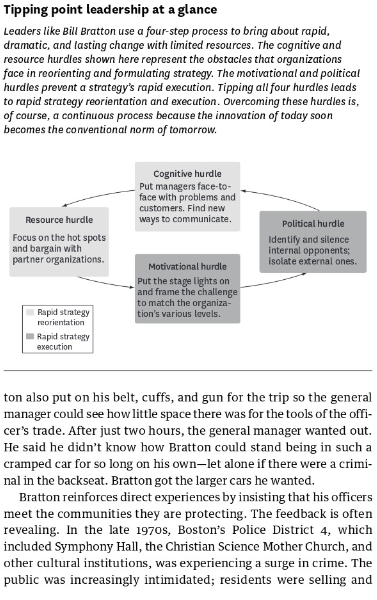

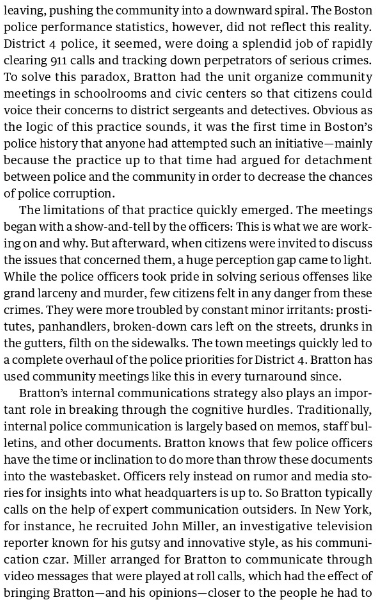

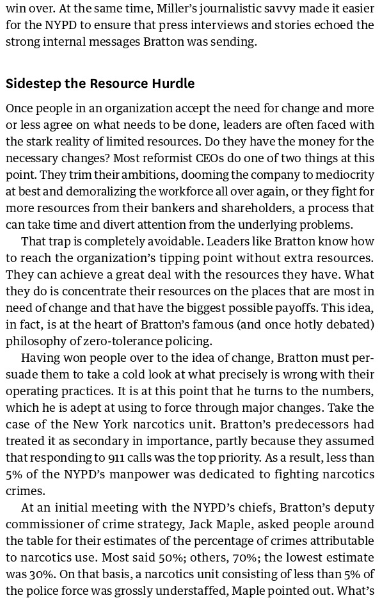

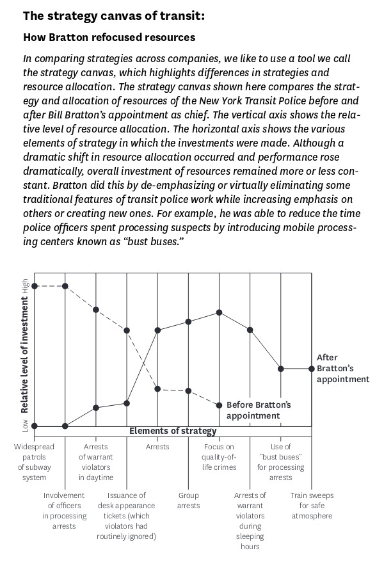

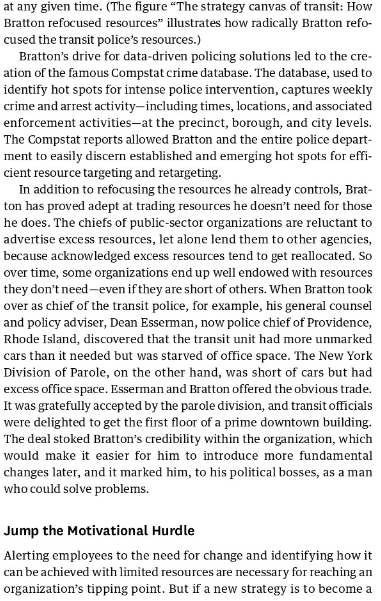

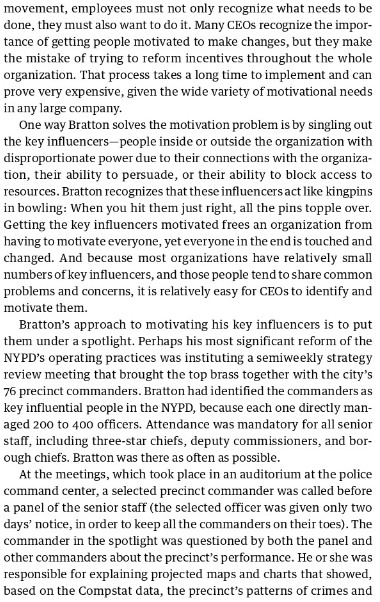

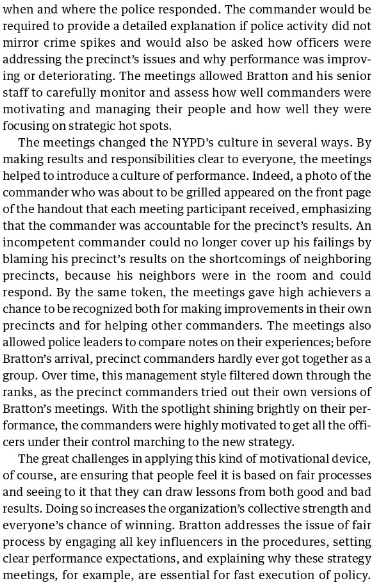

Tipping Point Leadership by W. Chan Kim and Rene Mauborgne IN FEBRUARY 1994, William Bratton was appointed police commis- sioner of New York City. The odds were against him. The New York Police Department, with a $2 billion budget and a workforce of 35,000 police officers, was notoriously difficult to manage. Turf wars over jurisdiction and funding were rife. Officers were under- paid relative to their counterparts in neighboring communities, and promotion seemed to bear little relationship to performance. Crime had gotten so far out of control that the press referred to the Big Apple as the Rotten Apple. Indeed, many social scientists had con- cluded, after three decades of increases, that New York City crime was impervious to police intervention. The best the police could do was react to crimes once they were committed. Yet in less than two years, and without an increase in his budget, Bill Bratton turned New York into the safest large city in the nation. Between 1994 and 1996, felony crime fell 39% ; murders, 50%; and theft, 35%. Gallup polls reported that public confidence in the NYPD jumped from 37% to 73%, even as internal surveys showed job sat- isfaction in the police department reaching an all-time high. Not surprisingly, Bratton's popularity soared, and in 1996, he was fea- tured on the cover of Time. Perhaps most impressive, the changes have outlasted their instigator, implying a fundamental shift in the department's organizational culture and strategy. Crime rates have continued to fall: Statistics released in December 2002 revealed that New York's overall crime rate is the lowest among the 25 largest cities in the United States. The NYPD turnaround would be impressive enough for any police chief. For Bratton, though, it is only the latest of no fewer than five successful turnarounds in a 20-year career in policing. In the hope that Bratton can repeat his New York and Boston successes, Los Angeles has recruited him to take on the challenge of turning around the LAPD. (For a summary of his achievements, see the table "Brat- ton in action.") So what makes Bill Bratton tick? As management researchers, we have long been fascinated by what triggers high performance or sud- denly brings an ailing organization back to life. In an effort to find the common elements underlying such leaps in performance, we have built a database of more than 125 business and nonbusiness organiza- tions. Bratton first caught our attention in the early 1990s, when we heard about his turnaround of the New York Transit Police. Bratton was special for us because in all of his turnarounds, he succeeded in record time despite facing all four of the hurdles that managers con- sistently claim block high performance: an organization wedded to the status quo, limited resources, a demotivated staff, and opposition from powerful vested interests. If Bratton could succeed against these odds, other leaders, we reasoned, could learn a lot from him. Over the years, through our professional and personal networks and the rich public information available on the police sector, we have systematically compared the strategic, managerial, and per- formance records of Bratton's turnarounds. We have followed up by interviewing the key players, including Bratton himself, as well as many other people who for professional-or sometimes personal- reasons tracked the events. Our research led us to conclude that all of Bratton's turnarounds are textbook examples of what we call tipping point leadership. The theory of tipping points, which has its roots in epidemiology, is well known; it hinges on the insight that in any organization, once the beliefs and energies of a critical mass of people are engaged, conver- sion to a new idea will spread like an epidemic, bringing about How can you overcome the hurdles facing any organization struggling to change: addiction to the status quo, limited resources, demoti- vated employees, and opposition from powerful vested interests? Take lessons from police chief Bill Bratton, who's pulled the trick off five times. Most dramatically, he transformed the U.S.'s most dangerous city-New York-into its safest. Bratton used tipping point leadership to make unarguable calls for change, concentrate resources on what really mattered, mobilize key players' commitment, and silence naysayers. Not every executive has Bratton's personality, but most have his potential-if they follow his suc- cess formula. fundamental change very quickly. The theory suggests that such a movement can be unleashed only by agents who make unforgettable and unarguable calls for change, who concentrate their resources on what really matters, who mobilize the commitment of the organiza- tion's key players, and who succeed in silencing the most vocal naysayers. Bratton did all of these things in all of his turnarounds. Most managers only dream of pulling off the kind of performance leaps Bratton delivered. Even Jack Welch needed some ten years and tens of millions of dollars of restructuring and training to turn GE into the powerhouse it is today. Few CEOs have the time and money that Welch had, and most-even those attempting relatively mild change-are soon daunted by the scale of the hurdles they face. Yet we have found that the dream can indeed become a reality. For what makes Bratton's turnarounds especially exciting to us is that his approach to overcoming the hurdles standing in the way of high performance has been remarkably consistent. His successes, there- fore, are not just a matter of personality but also of method, which suggests that they can be replicated. Tipping point leadership is learnable. In the following pages, we'll lay out the approach that has enabled Bratton to overcome the forces of inertia and reach the tip- ping point. We'll show first how Bratton overcame the cognitive hur- dles that block companies from recognizing the need for radical 2. Sidestep the resource hurdle. Four Steps to the Tipping Point 1. Break through the cognitive hurdle. To make a compelling case for change, don't just point at the numbers and demand better ones. Your abstract message won't stick. Instead, make key managers experience your organization's problems. Rather than trimming your ambi- tions (dooming your company to mediocrity) or fighting for more resources (draining attention from the underlying problems), concen- trate current resources on areas most needing change. Example: Since the majority of subway crimes occurred at only a few stations, Bratton focused manpower there- instead of putting a cop on every subway line, entrance, and exit. 3. Jump the motivational hurdle. Example: New Yorkers once viewed subways as the most dangerous places in their city. But the New York Transit Police's senior staff pooh-poohed pub- lic fears-because none had ever ridden subways. To shatter their complacency, Bratton required all NYTP officers- himself included to commute by subway. Seeing the jammed turnstiles, youth gangs, and derelicts, they grasped the need for change-and embraced responsibility for it. To turn a mere strategy into a movement, people must recog- nize what needs to be done and yearn to do it themselves. But don't try reforming your whole organization; that's cumbersome and expensive. Instead, motivate key influencers-persuasive change. Then we'll describe how he successfully managed around the public sector's endemic constraints on resources, which he even turned to his advantage. In the third section, we'll explain how Brat- ton overcame the motivational hurdles that had discouraged and demoralized even the most eager police officers. Finally, we'll describe how Bratton neatly closed off potentially fatal resistance from vocal and powerful opponents. (For a graphic summary of the ideas expressed in this article, see the figure "Tipping point leader- ship at a glance.") 4. Knock over the political hurdle. people with multiple connections. Like bowling kingpins hit straight on, they topple all the other pins. Most organizations have several key influencers who share com- mon problems and concerns- making it easy to identify and motivate them. Even when organizations reach their tipping points, powerful vested interests resist change. Identify and silence key naysay- ers early by putting a respected senior insider on your top team. Example: Bratton put the NYPD's key influencers- precinct commanders-under a spotlight during semiweekly crime strategy review meet- ings, where peers and superiors grilled commanders about precinct performance. Results? A culture of perform- ance, accountability, and learning that commanders replicated down the ranks. Example: At the NYPD, Bratton appointed 20-year veteran cop John Timoney as his number two. Timoney knew the key players and how they played the political game. Early on, he identified likely saboteurs and resisters among top staff-prompting a changing of the guard. Also make challenges attainable. Bratton exhorted staff to make NYC's streets safe "block by block, precinct by precinct, and borough by borough." Also, silence opposition with indisputable facts. When Bratton proved his proposed crime- reporting system required less than 18 minutes a day, time- crunched precinct commanders adopted it. Break Through the Cognitive Hurdle In many turnarounds, the hardest battle is simply getting people to agree on the causes of current problems and the need for change. Most CEOs try to make the case for change simply by pointing to the numbers and insisting that the company achieve better ones. But messages communicated through numbers seldom stick. To the line managers-the very people the CEO needs to win over-the case for change seems abstract and remote. Those whose units are doing well feel that the criticism is not directed at them, that the problem Bratton in action The New York Police Department was not Bill Bratton's first tumaround. The table describes his biggest challenges and achievements during his 20 years as a policy reformer. Domain Massachu- Boston New York New York Boston Police Dis- trict 4 Metropolitan Transit Police Police Depart- setts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) Police ("The Mets") (NYTP) ment (NYPD) Years 1977-1982 1983-1986 1986-1990 1990-1992 1994-1996 Position Sergeant, Superin- Superin- Chief of police Commis- lieutenant tendent tendent sioner Setting Assaults, The Mets Crime had Subway crime had been on the lacked modern equipment, procedures, and discipline. The middle class was fleeing to the suburbs in search of a risen 25% per year in the past three years-twice the overall rate for the city. rise for the past five years. better qual- Physical facili- The media ity of life. dubbed the ties were crumbling. Boston sub- way the Ter- ror Train. Accountability, discipline, and morale were low in the 600- person Mets Subway use by the public had declined sharply; polls indicated that New Yorkers considered There was public. despair in the face of the high crime rate. The Boston Crime was workforce. the subway seen as part Globe published a series on police incompe- the most dan- gerous place in the city. of a break- down of social tence in norms. the MBTA. There were 170,000 fare The budget evaders per for policing day, costing was shrink- the city $80 million ing. The NYPD annually. budget (aside from Aggressive panhandling and vandalism were endemic. More than 5,000 people were living in the subway system. personnel) was being cut by 35%. The staff was demor- alized and relatively underpaid. drug dealing. prostitution, public drink- ing, and graffiti were endemic to the area. The Boston public shied away from attending baseball games and other events and from shopping in the Fenway neighbor- hood for fear of being robbed or attacked or having their cars stolen. Domain Boston Results Massachu- Boston New York New York Transit setts Bay Metropolitan Police Police Depart- Police ("The Mets") Authority (NYTP) ment (MBTA) (NYPD) Overall crime Crime on the MBTA decreased by 27%; arrests rose to 1,600 per year from Employee morale rose as Bratton instilled fell by 17%. In two years. Bratton reduced felony crime Felony crime fell by 39%. accountability, protocol, and pride. Murders fell by 22%, with robberies down by 40%. 600. by 50%. Theft fell by Increased 35% (rob- beries were The MBTA police met more than 800 standards of excellence to be accre. dited by the National Com- mission on Accreditation In three years, the Metropoli tan Police changed from a dispirited, do- nothing, reac- tive confidence in the subway led to increased ridership. down by one-third, burglaries by one- organization quarter). Fare evasion was cut in half. with a poor self-image and an even There were 200,000 for Police Agencies. It fewer victims worse public Equipment acquired dur a year than in image to a very 1990. was only the 13th police department in proud, proac- tive depart- ment. the country to meet this standard. Equipment acquired dur- ing his tenure: 100 new ing his tenure: a state-of- the-art communica- tion system, advanced handguns for officers, and new patrol cars (the number of cars doubled). By the end of Bratton's tenure, the NYPD had a 73% positive rating, up from 37% Equipment acquired dur- ing his tenure: 55 new mid- size cars, new uniforms, and new logos. four years earlier. vehicles, a heli- copter, and a state-of-the- art radio system. Ridership began to grow. is top management's. Managers of poorly performing units feel that they have been put on notice-and people worried about job secu- rity are more likely to be scanning the job market than trying to solve the company's problems. For all these reasons, tipping point leaders like Bratton do not rely on numbers to break through the organization's cognitive hurdles. Police District 4 Transit Crime throughout the Fenway area was dramatically reduced. Tourists, residents, and investment returned as an entire area of the city rebounded. Instead, they put their key managers face-to-face with the opera- tional problems so that the managers cannot evade reality. Poor per- formance becomes something they witness rather than hear about. Communicating in this way means that the message-performance is poor and needs to be fixed-sticks with people, which is essential if they are to be convinced not only that a turnaround is necessary but that it is something they can achieve. When Bratton first went to New York to head the transit police in April 1990, he discovered that none of the senior staff officers rode the subway. They commuted to work and traveled around in cars provided by the city. Comfortably removed from the facts of under- ground life-and reassured by statistics showing that only 3% of the city's major crimes were committed in the subway-the senior man- agers had little sensitivity to riders' widespread concern about safety. In order to shatter the staff's complacency, Bratton began requiring that all transit police officials-beginning with himself- ride the subway to work, to meetings, and at night. It was many staff officers' first occasion in years to share the ordinary citizen's subway experience and see the situation their subordinates were up against: jammed turnstiles, aggressive beggars, gangs of youths jumping turnstiles and jostling people on the platforms, winos and homeless people sprawled on benches. It was clear that even if few major crimes took place in the subway, the whole place reeked of fear and disorder. With that ugly reality staring them in the face, the transit force's senior managers could no longer deny the need for a change in their policing methods. Bratton uses a similar approach to help sensitize his superiors to his problems. For instance, when he was running the police division of the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA), which runs the Boston-area subway and buses, the transit authority's board decided to purchase small squad cars that would be cheaper to buy and run. Instead of fighting the decision, Bratton invited the MBTA's general manager for a tour of the district. He picked him up in a small car just like the ones that were to be ordered. He jammed the seats forward to let the general manager feel how little legroom a six-foot cop would have, then drove him over every pothole he could find. Brat- Tipping point leadership at a glance Leaders like Bill Bratton use a four-step process to bring about rapid, dramatic, and lasting change with limited resources. The cognitive and resource hurdles shown here represent the obstacles that organizations face in reorienting and formulating strategy. The motivational and political hurdles prevent a strategy's rapid execution. Tipping all four hurdles leads to rapid strategy reorientation and execution. Overcoming these hurdles is, of course, a continuous process because the innovation of today soon becomes the conventional norm of tomorrow. Cognitive hurdle Put managers face-to- face with problems and customers. Find new ways to communicate. Resource hurdle Focus on the hot spots and bargain with partner organizations. Political hurdle Identify and silence internal opponents; isolate external ones. Motivational hurdle Put the stage lights on and frame the challenge to match the organiza- tion's various levels. Rapid strategy reorientation Rapid strategy execution ton also put on his belt, cuffs, and gun for the trip so the general manager could see how little space there was for the tools of the offi- cer's trade. After just two hours, the general manager wanted out. He said he didn't know how Bratton could stand being in such a cramped car for so long on his own-let alone if there were a crimi- nal in the backseat. Bratton got the larger cars he wanted. Bratton reinforces direct experiences by insisting that his officers meet the communities they are protecting. The feedback is often revealing. In the late 1970s, Boston's Police District 4, which included Symphony Hall, the Christian Science Mother Church, and other cultural institutions, was experiencing a surge in crime. The public was increasingly intimidated; residents were selling and leaving, pushing the community into a downward spiral. The Boston police performance statistics, however, did not reflect this reality. District 4 police, it seemed, were doing a splendid job of rapidly clearing 911 calls and tracking down perpetrators of serious crimes. To solve this paradox, Bratton had the unit organize community meetings in schoolrooms and civic centers so that citizens could voice their concerns to district sergeants and detectives. Obvious as the logic of this practice sounds, it was the first time in Boston's police history that anyone had attempted such an initiative-mainly because the practice up to that time had argued for detachment between police and the community in order to decrease the chances of police corruption. The limitations of that practice quickly emerged. The meetings began with a show-and-tell by the officers: This is what we are work- ing on and why. But afterward, when citizens were invited to discuss the issues that concerned them, a huge perception gap came to light. While the police officers took pride in solving serious offenses like grand larceny and murder, few citizens felt in any danger from these crimes. They were more troubled by constant minor irritants: prosti- tutes, panhandlers, broken-down cars left on the streets, drunks in the gutters, filth on the sidewalks. The town meetings quickly led to a complete overhaul of the police priorities for District 4. Bratton has used community meetings like this in every turnaround since. Bratton's internal communications strategy also plays an impor- tant role in breaking through the cognitive hurdles. Traditionally, internal police communication is largely based on memos, staff bul- letins, and other documents. Bratton knows that few police officers have the time or inclination to do more than throw these documents into the wastebasket. Officers rely instead on rumor and media sto- ries for insights into what headquarters is up to. So Bratton typically calls on the help of expert communication outsiders. In New York, for instance, he recruited John Miller, an investigative television reporter known for his gutsy and innovative style, as his communi- cation czar. Miller arranged for Bratton to communicate through video messages that were played at roll calls, which had the effect of bringing Bratton-and his opinions-closer to the people he had to win over. At the same time, Miller's journalistic savvy made it easier for the NYPD to ensure that press interviews and stories echoed the strong internal messages Bratton was sending. Sidestep the Resource Hurdle Once people in an organization accept the need for change and more or less agree on what needs to be done, leaders are often faced with the stark reality of limited resources. Do they have the money for the necessary changes? Most reformist CEOs do one of two things at this point. They trim their ambitions, dooming the company to mediocrity at best and demoralizing the workforce all over again, or they fight for more resources from their bankers and shareholders, a process that can take time and divert attention from the underlying problems. That trap is completely avoidable. Leaders like Bratton know how to reach the organization's tipping point without extra resources. They can achieve a great deal with the resources they have. What they do is concentrate their resources on the places that are most in need of change and that have the biggest possible payoffs. This idea, in fact, is at the heart of Bratton's famous (and once hotly debated) philosophy of zero-tolerance policing. Having won people over to the idea of change, Bratton must per- suade them to take a cold look at what precisely is wrong with their operating practices. It is at this point that he turns to the numbers, which he is adept at using to force through major changes. Take the case of the New York narcotics unit. Bratton's predecessors had treated it as secondary in importance, partly because they assumed that responding to 911 calls was the top priority. As a result, less than 5% of the NYPD's manpower was dedicated to fighting narcotics crimes. At an initial meeting with the NYPD's chiefs, Bratton's deputy commissioner of crime strategy, Jack Maple, asked people around the table for their estimates of the percentage of crimes attributable to narcotics use. Most said 50%; others, 70%; the lowest estimate was 30%. On that basis, a narcotics unit consisting of less than 5% of the police force was grossly understaffed, Maple pointed out. What's The strategy canvas of transit: How Bratton refocused resources In comparing strategies across companies, we like to use a tool we call the strategy canvas, which highlights differences in strategies and resource allocation. The strategy canvas shown here compares the strat- egy and allocation of resources of the New York Transit Police before and after Bill Bratton's appointment as chief. The vertical axis shows the rela- tive level of resource allocation. The horizontal axis shows the various elements of strategy in which the investments were made. Although a dramatic shift in resource allocation occurred and performance rose dramatically, overall investment of resources remained more or less con- stant. Bratton did this by de-emphasizing or virtually eliminating some traditional features of transit police work while increasing emphasis on others or creating new ones. For example, he was able to reduce the time police officers spent processing suspects by introducing mobile process- ing centers known as "bust buses." After Bratton's appointment Before Bratton's appointment Elements of strategy Arrests Relative level of investment High Widespread patrols of subway system Arrests of warrant violators in daytime Involvement of officers in processing arrests Issuance of desk appearance tickets (which violators had routinely ignored) Group arrests Focus on quality-of- life crimes Use of "bust buses" for processing arrests Arrests of warrant violators during sleeping hours Train sweeps for safe atmosphere. more, it turned out that the narcotics squad largely worked Monday through Friday, even though drugs were sold in large quantities- and drug-related crimes persistently occurred-on the weekends. Why the weekday schedule? Because it had always been done that way; it was an unquestioned modus operandi. Once these facts were presented, Bratton's call for a major reallocation of staff and resources within the NYPD was quickly accepted. A careful examination of the facts can also reveal where changes in key policies can reduce the need for resources, as Bratton demon- strated during his tenure as chief of New York's transit police. His predecessors had lobbied hard for the money to increase the number of subway cops, arguing that the only way to stop muggers was to have officers ride every subway line and patrol each of the system's 700 exits and entrances. Bratton, by contrast, believed that subway crime could be resolved not by throwing more resources at the prob- lem but by better targeting those resources. To prove the point, he had members of his staff analyze where subway crimes were being committed. They found that the vast majority occurred at only a few stations and on a couple of lines, which suggested that a targeted strategy would work well. At the same time, he shifted more of the force out of uniform and into plain clothes at the hot spots. Crimi- nals soon realized that an absence of uniforms did not necessarily mean an absence of cops. Distribution of officers was not the only problem. Bratton's analy- sis revealed that an inordinate amount of police time was wasted in processing arrests. It took an officer up to 16 hours per arrest to book the suspect and file papers on the incident. What's more, the officers so hated the bureaucratic process that they avoided making arrests in minor cases. Bratton realized that he could dramatically increase his available policing resources-not to mention the officers' motivation if he could somehow improvise around this problem. His solution was to park "bust buses"-old buses converted into arrest-processing centers-around the corner from targeted subway stations. Processing time was cut from 16 hours to just one. Innova- tions like that enabled Bratton to dramatically reduce subway crime-even without an increase in the number of officers on duty at any given time. (The figure "The strategy canvas of transit: How Bratton refocused resources" illustrates how radically Bratton refo- cused the transit police's resources.) Bratton's drive for data-driven policing solutions led to the cre- ation of the famous Compstat crime database. The database, used to identify hot spots for intense police intervention, captures weekly crime and arrest activity-including times, locations, and associated enforcement activities at the precinct, borough, and city levels. The Compstat reports allowed Bratton and the entire police depart- ment to easily discern established and emerging hot spots for effi- cient resource targeting and retargeting. In addition to refocusing the resources he already controls, Brat- ton has proved adept at trading resources he doesn't need for those he does. The chiefs of public-sector organizations are reluctant to advertise excess resources, let alone lend them to other agencies, because acknowledged excess resources tend to get reallocated. So over time, some organizations end up well endowed with resources they don't need-even if they are short of others. When Bratton took over as chief of the transit police, for example, his general counsel and policy adviser, Dean Esserman, now police chief of Providence, Rhode Island, discovered that the transit unit had more unmarked cars than it needed but was starved of office space. The New York Division of Parole, on the other hand, was short of cars but had excess office space. Esserman and Bratton offered the obvious trade. It was gratefully accepted by the parole division, and transit officials were delighted to get the first floor of a prime downtown building. The deal stoked Bratton's credibility within the organization, which would make it easier for him to introduce more fundamental changes later, and it marked him, to his political bosses, as a man who could solve problems. Jump the Motivational Hurdle Alerting employees to the need for change and identifying how it can be achieved with limited resources are necessary for reaching an organization's tipping point. But if a new strategy is to become a movement, employees must not only recognize what needs to be done, they must also want to do it. Many CEOs recognize the impor- tance of getting people motivated to make changes, but they make the mistake of trying to reform incentives throughout the whole organization. That process takes a long time to implement and can prove very expensive, given the wide variety of motivational needs in any large company. One way Bratton solves the motivation problem is by singling out the key influencers-people inside or outside the organization with disproportionate power due to their connections with the organiza- tion, their ability to persuade, or their ability to block access to resources. Bratton recognizes that these influencers act like kingpins in bowling: When you hit them just right, all the pins topple over. Getting the key influencers motivated frees an organization from having to motivate everyone, yet everyone in the end is touched and changed. And because most organizations have relatively small numbers of key influencers, and those people tend to share common problems and concerns, it is relatively easy for CEOs to identify and motivate them. Bratton's approach to motivating his key influencers is to put them under a spotlight. Perhaps his most significant reform of the NYPD's operating practices was instituting a semiweekly strategy review meeting that brought the top brass together with the city's 76 precinct commanders. Bratton had identified the commanders as key influential people in the NYPD, because each one directly man- aged 200 to 400 officers. Attendance was mandatory for all senior staff, including three-star chiefs, deputy commissioners, and bor- ough chiefs. Bratton was there as often as possible. At the meetings, which took place in an auditorium at the police command center, a selected precinct commander was called before a panel of the senior staff (the selected officer was given only two days' notice, in order to keep all the commanders on their toes). The commander in the spotlight was questioned by both the panel and other commanders about the precinct's performance. He or she was responsible for explaining projected maps and charts that showed, based on the Compstat data, the precinct's patterns of crimes and when and where the police responded. The commander would be required to provide a detailed explanation if police activity did not mirror crime spikes and would also be asked how officers were addressing the precinct's issues and why performance was improv- ing or deteriorating. The meetings allowed Bratton and his senior staff to carefully monitor and assess how well commanders were motivating and managing their people and how well they were focusing on strategic hot spots. The meetings changed the NYPD's culture in several ways. By making results and responsibilities clear to everyone, the meetings helped to introduce a culture of performance. Indeed, a photo of the commander who was about to be grilled appeared on the front page of the handout that each meeting participant received, emphasizing that the commander was accountable for the precinct's results. An incompetent commander could no longer cover up his failings by blaming his precinct's results on the shortcomings of neighboring precincts, because his neighbors were in the room and could respond. By the same token, the meetings gave high achievers a chance to be recognized both for making improvements in their own precincts and for helping other commanders. The meetings also allowed police leaders to compare notes on their experiences; before Bratton's arrival, precinct commanders hardly ever got together as a group. Over time, this management style filtered down through the ranks, as the precinct commanders tried out their own versions of Bratton's meetings. With the spotlight shining brightly on their per- formance, the commanders were highly motivated to get all the offi- cers under their control marching to the new strategy. The great challenges in applying this kind of motivational device, of course, are ensuring that people feel it is based on fair processes and seeing to it that they can draw lessons from both good and bad results. Doing so increases the organization's collective strength and everyone's chance of winning. Bratton addresses the issue of fair process by engaging all key influencers in the procedures, setting clear performance expectations, and explaining why these strategy meetings, for example, are essential for fast execution of policy. He addresses the issue of learning by insisting that the team of top brass play an active role in meetings and by being an active modera- tor himself. Precinct commanders can talk about their achievements or failures without feeling that they are showing off or being shown up. Successful commanders aren't seen as bragging, because it's clear to everyone that they were asked by Bratton's top team to show, in detail, how they achieved their successes. And for com- manders on the receiving end, the sting of having to be taught a les- son by a colleague is mitigated, at least, by their not having to suffer the indignity of asking for it. Bratton's popularity soared when he created a humorous video satirizing the grilling that precinct com- manders were given; it showed the cops that he understood just how much he was asking of them. Bratton also uses another motivational lever: framing the reform challenge itself. Framing the challenge is one of the most subtle and sensitive tasks of the tipping point leader; unless people believe that results are attainable, a turnaround is unlikely to succeed. On the face of it, Bratton's goal in New York was so ambitious as to be scarcely believable. Who would believe that the city could be made one of the safest in the country? And who would want to invest time and energy in chasing such an impossible dream? To make the challenge seem manageable, Bratton framed it as a series of specific goals that officers at different levels could relate to. As he put it, the challenge the NYPD faced was to make the streets of New York safe "block by block, precinct by precinct, and borough by borough." Thus framed, the task was both all encompassing and doable. For the cops on the street, the challenge was making their beats or blocks safe-no more. For the commanders, the challenge was making their precincts safe-no more. Borough heads also had a concrete goal within their capabilities: making their boroughs safe- no more. No matter what their positions, officers couldn't say that what was being asked of them was too tough. Nor could they claim that achieving it was out of their hands. In this way, responsibility for the turnaround shifted from Bratton to each of the thousands of police officers on the force. Knock Over the Political Hurdle Organizational politics is an inescapable reality in public and corpo- rate life, a lesson Bratton learned the hard way. In 1980, at age 34 one of the youngest lieutenants in Boston's police department, he had proudly put up a plaque in his office that said: "Youth and skill will win out every time over age and treachery." Within just a few months, having been shunted into a dead-end position due to a mixture of office politics and his own brashness, Bratton took the sign down. He never again forgot the importance of understanding the plotting, intrigue, and politics involved in pushing through change. Even if an organization has reached the tipping point, powerful vested interests will resist the impending reforms. The more likely change becomes, the more fiercely and vocally these negative influencers-both inter- nal and external-will fight to protect their positions, and their resist- ance can seriously damage, even derail, the reform process. Bratton anticipates these dangers by identifying and silencing powerful naysayers early on. To that end, he always ensures that he has a respected senior insider on the top team. At the NYPD, for instance, Bratton appointed John Timoney, now Miami's police com- missioner, as his number two. Timoney was a cop's cop, respected and feared for his dedication to the NYPD and for the more than 60 decorations he had received. Twenty years in the ranks had taught him who all the key players were and how they played the political game. One of the first tasks Timoney carried out was to report to Bratton on the likely attitudes of the top staff toward Bratton's con- cept of zero-tolerance policing, identifying those who would fight or silently sabotage the new initiatives. This led to a dramatic changing of the guard. Of course, not all naysayers should face the ultimate sanction- there might not be enough people left to man the barricades. In many cases, therefore, Bratton silences opposition by example and indis- putable fact. For instance, when first asked to compile detailed crime maps and information packages for the strategy review meetings, most precinct commanders complained that the task would take too long and waste valuable police time that could be better spent fighting crime. Anticipating this argument, deputy commissioner Jack Maple set up a reporting system that covered the city's most crime-ridden areas. Operating the system required no more than 18 minutes a day, which worked out, as he told the precinct commanders, to less than 1% of the average precinct's workload. Try to argue with that. Often the most serious opposition to reform comes from outside. In the public sector, as in business, an organization's change of strat- egy has an impact on other organizations-partners and competitors alike. The change is likely to be resisted by those players if they are happy with the status quo and powerful enough to protest the changes. Bratton's strategy for dealing with such opponents is to iso- late them by building a broad coalition with the other independent powers in his realm. In New York, for example, one of the most seri- ous threats to his reforms came from the city's courts, which were concerned that zero-tolerance policing would result in an enormous number of small-crimes cases clogging the court schedule. To get past the opposition of the courts, Bratton solicited the sup- port of no less a personage than the mayor, Rudolph Giuliani, who had considerable influence over the district attorneys, the courts, and the city jail on Rikers Island. Bratton's team demonstrated to the mayor that the court system had the capacity to handle minor "qual- ity of life" crimes, even though doing so would presumably not be palatable for them. The mayor decided to intervene. While conceding to the courts that a crackdown campaign would cause a short-term spike in court work, he also made clear that he and the NYPD believed it would eventually lead to a workload reduction for the courts. Working together in this way, Bratton and the mayor were able to maneuver the courts into processing quality-of-life crimes. Seeing that the mayor was aligned with Bratton, the courts appealed to the city's legislators, advocating legislation to exempt them from handling minor-crime cases on the grounds that such cases would clog the system and entail significant costs to the city. Bratton and the mayor, who were holding weekly strategy meetings, added another ally to their coalition by placing their case before the press, in partic- ular the New York Times. Through a series of press conferences and articles and at every interview opportunity, the issue of zero toler- ance was put at the front and center of public debate with a clear, simple message: If the courts did not help crack down on quality-of- life crimes, the city's crime rates would not improve. It was a matter not of saving dollars but of saving the city. Bratton's alliance with the mayor's office and the city's leading media institution successfully isolated the courts. The courts could hardly be seen as publicly opposing an initiative that would not only make New York a more attractive place to live but would ultimately reduce the number of cases brought before them. With the mayor speaking aggressively in the press about the need to pursue quality- of-life crimes and the city's most respected-and liberal-newspa- per giving credence to the policy, the costs of fighting Bratton's strategy were daunting. Thanks to this savvy politicking, one of Bratton's biggest battles was won, and the legislation was not enacted. The courts would handle quality-of-life crimes. In due course, the crime rates did indeed come tumbling down. Of course, Bill Bratton, like any leader, must share the credit for his successes. Turning around an organization as large and as wedded to the status quo as the NYPD requires a collective effort. But the tip- ping point would not have been reached without him-or another leader like him. And while we recognize that not every executive has the personality to be a Bill Bratton, there are many who have that potential once they know the formula for success. It is that formula that we have tried to present, and we urge managers who wish to turn their companies around, but have limited time and resources, to take note. By addressing the hurdles to tipping point change described in these pages, they will stand a chance of achieving the same kind of results for their shareholders as Bratton has delivered to the citizens of New York

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts