Everybody knows what a grand piano looks like, although its hard to describe its contour as anything

Question:

Everybody knows what a grand piano looks like, although it’s hard to describe its contour as anything other than “piano shaped.” From a bird’s-eye view, you might recognize something like a great big holster. The case—the curved lateral surface that runs around the whole instrument— appears to be a single continuous piece of wood, but it isn’t really. If you look carefully at the case of a piano built by Steinway & Sons, you’ll see that you’re actually looking at a remarkable composite of raw material, craftsmanship, and technology. The process by which this component is made— like most of the processes for making a Steinway grand—is a prime example of a technical, or task, subsystem at work in a highly specialized factory.

The case starts out as a rim, which is constructed out of separate slats of wood, mostly maple (eastern rock maple, to be precise). Once raw boards have been cut and planed, they’re glued along their lengthwise edges to the width of 12½ inches. These composite pieces are then jointed and glued end to end to form slats 22 feet long—the measure of the piano’s perimeter. Next, a total of 18 separate slats—14 layers of maple and four layers of other types of wood—are glued and stacked together to form a book—one (seemingly) continuous “board” 3¼ inches thick. Then comes the process that’s a favorite of visitors on the Steinway factory tour—bending this rim into the shape of a piano. Steinway does it pretty much the same way that it has for more than a century—by hand and all at once. Because the special glue is in the process of drying, a crew of six has just 20 minutes to wrestle the book, with block and tackle and wooden levers and mallets, into a rim-bending press—“a giant piano shaped vise,” as Steinway describes it—which will force the wood to “forget” its natural inclination to be straight and assume the familiar contour of a grand piano.

Visitors report the sound of splintering wood, but Steinway artisans assure them that the specially cured wood isn’t likely to break or the specially mixed glue to lose its grip. It’s a good thing, too, both because the wood is expensive and because the precision Steinway process can’t afford much wasted effort. The company needs 12 months, 12,000 parts, 450 craftspeople, and countless hours of skilled labor to produce a grand piano. Today, the New York factory turns out about 10 pianos in a day or 2,500 a year. (A mass producer might build 2,000 pianos a week.) The result of this painstaking task system, according to one business journalist with a good ear, is “both impossibly perfect instruments and a scarcity,” and that’s why Steinways are so expensive—currently, somewhere between $45,000 and $110,000.

But Steinway pianos, the company reminds potential buyers, have always been “built to a standard, not to a price.” “It’s a product,” says company executive Leo F. Spellman, “that in some sense speaks to people and will have a legacy long after we’re gone. What [Steinway] craftsmen work on today will be here for another 50 or 100 years.” Approximately 90 percent of all concert pianists prefer the sound of a Steinway, and the company’s attention to manufacturing detail reflects the fact that when a piano is being played, the entire instrument vibrates—and thus affects its sound. In other words—and not surprisingly—the better the raw materials, design, and construction, the better the sound.

That’s one of the reasons Steinway craftsmen put so much care into the construction of the piano’s case: It’s a major factor in the way the body of the instrument resonates. The maple wood for the case, for example, arrives at the factory with a water content of 80 percent. It’s then dried, both in the open air and in kilns, until the water content is reduced to about 10 percent—suitable for both strength and pliability. To ensure that strength and pliability remain stable, the slats must be cut so that they’re horizontally grained and arranged, with the “inside” of one slat—the side that grew toward the center of the tree—facing the “outside” of the next one in the book. The case is removed from the press after one day and then stored for ten weeks in a humidity-controlled rim-bending room. Afterward, it’s ready to be sawed, planed, and sanded to specification—a process called frazing. A black lacquer finish is added, and only then is the case ready to be installed as a component of a grand piano in progress.

The Steinway process also puts a premium on skilled workers. Steinway has always been an employer of immigrant labor, beginning with the German craftsmen and laborers hired by founder Henry Steinway in the 1860s and 1870s. Today, Steinway employees come from much different places—Haitians and Dominicans in the 1980s, exiles from war-torn Yugoslavia in the 1990s—and it still takes time to train them. It takes about a year, for instance, to train a case maker, and “when you lose one of them for a long period of time,” says Gino Romano, a senior supervisor hired in 1964, “it has a serious effect on our output.” Romano recalls one year in mid-June when a case maker was injured in a car accident and was out for several weeks. His department fell behind schedule, and it was September before Romano could find a suitable replacement (an experienced case maker in Florida who happened to be a relative of another Steinway worker).

The company’s employees don’t necessarily share Spell man’s sense of the company’s legacy, but many of them are well aware of the brand recognition commanded by the products they craft, according to Romano:

Case Questions

1. Explain the process by which a Steinway grand piano is constructed as a subsystem of a larger system. From what the text tells you, give some examples of how the production subsystem is affected by the management, financial, and marketing subsystems.

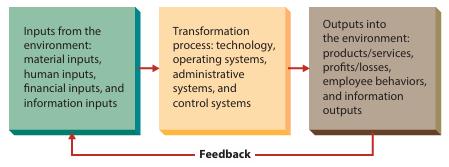

2. Discuss the Steinway process in terms of the systems perspective of organizations summarized in Figure 1.4Explain the role of each of the three elements highlighted by the figure—inputs from the environment, the transformation process, and outputs into the environment.

Figure 1.4.

3. Discuss some of the ways the principles of behavioral management and operations management can throw light on the Steinway process. How about the contingency perspective? In what ways does the Steinway process reflect a universal perspective, and in what ways does it reflect a contingency perspective?

Step by Step Answer: