![]()

![]() New Semester Started

Get 50% OFF

Study Help!

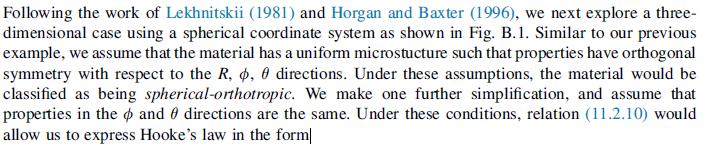

--h --m --s

Claim Now

New Semester Started

Get 50% OFF

Study Help!

--h --m --s

Claim Now

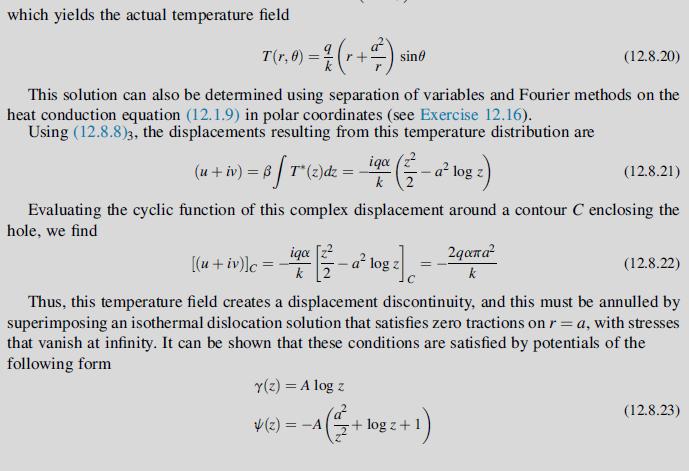

![]()

![]()

![or 3 + verpw (a -n-1-1) 9-n de pw 3- - [n(3 + vor) a-npn-1 - (n +3ver)r] n Discuss issues with the case n < 1](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/2/6/23965a2295fa1f9b1705126239050.jpg)

![3P [cxy- 4c3 xy S16 -+ 3 6511 - (26x - y)] 3P 0x = -2-3x - 2018 (G-2). ox xy+ 3P S16 2c3 S113 satisfies the](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/2/6/36765a229df7c50a1705126366841.jpg)

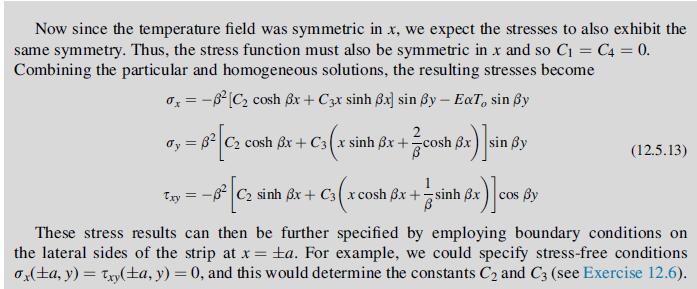

![o = - [C cosh 3x + C3x sinh 6x] sin y - ExT, sin By y = 6 C cosh 8x + C3 (x sinh .x+cosh Bx) sin By -0 C2 C](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/2/8/13865a230ca55e2d1705128137526.jpg)

![= 0= r dr + Ea-. (2) PI r drdr + + { [ ( ^ ) : ] } ? P PI](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/2/8/30265a2316e0ba661705128301516.jpg)

![9x = Jy = 'du' dv + dy Txy = 'du' dv + x du dv - (+) +2- + [2B(2+u) - a(3 +2)]T du' x v' +2+ [2B(2+) -](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/2/9/26465a2353081ad11705129263953.jpg)

![Je e Exqa/k For the cases m = (1 +m)[(1 +m+ m) sino - msin30] (1-2m cos20+ m) = 0, 1/2, +1, plot and compare](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/3/0/36965a23981a5fbb1705130368956.jpg)

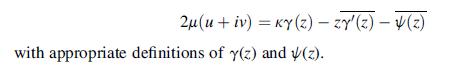

![P R U= "=+HAR [1 + +(1-2) (~+2 (8+2F)] 4R R+z (R+z) Pxy 1 1-2v Px 12v V = -PR (= (R+2)+). " === (+1=) W 4R 4](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/3/3/16765a2446f2394e1705133166527.jpg)

![Ur = P 4R U = P [2(1 1) + } +] 4THR 2(1 R rz (1-2v)r] R R+z Ug = 0](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/3/5/62065a24e044c3a31705135619841.jpg)

![lim [o,(r,z) o,(r,z+ d)] : = OR dor z TRO -d- D 8T (1- - v) dz The other stress components follow in an](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/3/6/03065a24f9e562a81705136029745.jpg)

![1 - 2v 1-2v OR=S[1 +2= # ()], 06-0$ - $[1-1- = 1+v 1+v = (2)](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/3/7/01365a2537568b9a1705137012752.jpg)

![0= d dr2 2011) (2-[(-(-3) (4]](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/4/2/61065a26952561bf1705142609731.jpg)

![or 0 Pia(2+k-n)/2 bk - ak [p(2+k+n)/2 _ fkp(2k+n)/2] Pia(2+k-n)/2 [2 + kv-nv bk - ak k-n+2v (-2+k+n)/2 +](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/4/3/66065a26d6c79cd41705143659921.jpg)

![or = e Pia(2+k-n)/2 bk - ak [ r(-2+k+n)/2 _ Bp(-2-k+n)/2] Pia(2+k-n)/2 [2 + kv- k - nv k-n+2v 2-kv - nv](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/4/4/51665a270c425cf91705144515700.jpg)

![(r) = [2(a-1) | -^ a[r - + Man (-1), m 3 a m = 1 2 n 08|1 + ] + ^ [ - (9) log|1 + r)], m log|1+n|| 1+ n m =](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/1/4/6/64865a27918624c81705146647867.jpg)

![p cot a -2 (1-a cota) [- tan a + xy + (x + y) (a tan-)] solves this plane problem. For the particular case](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/0/4/1/06765a0dcab3815f1705041066884.jpg)

![p=[a14 cos 0 + b14 sin 0 + a31 cos 30 + b31 sin 30] solves this plane problem. p(x) = kx r 0 X](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/0/4/1/17665a0dd18a11eb1705041176298.jpg)

![= eix [Aey + Be By + Cyey + Dye By] teix A'ey + B'e By + C'yeby +D'ye By]](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/0/4/5/10665a0ec728fc831705045106108.jpg)

![0x = Ox 2 Txy M dy=[cos20 - cos201)] 2 [4log(sin0/sin0) - cos202 + cos201)] X t 2 [2(02-01)+sin202 - sin201]](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/0/4/5/37965a0ed83ae8131705045379142.jpg)

![Or = 00 4M [ab N Tre = 0 4M -1 N log (2) 10 | + b log(7) + a log(7)] ab log (2) + b log (2) + a log () + d]](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/images/question_images/1705/0/4/6/57065a0f22a129ea1705046569512.jpg)